Great Barrier Reef

The Great Barrier Reef, the world's largest coral reef system, comprises roughly three thousand individual reefs and nine hundred islands stretching for 1,616 miles (2,586 kilometers) and covering an area of approximately 214,000 square miles (554,260 square kilometers). The reef is located in the Coral Sea, off the coast of Queensland in northeast Australia. A large part of the reef is protected by the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority (GBRMPA).

The Great Barrier Reef can be seen from space and is sometimes referred to as the single largest organism in the world. In reality, it is a complex ecosystem comprising many billions of tiny organisms, known as coral polyps, living in harmony with countless species of rare and exquisite flora and fauna. The reef was also selected as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1981, and it has been labeled as one of the seven natural wonders of the world. The Queensland National Trust has named it a state icon of Queensland. Each year, some 2 million tourists from around the world come to swim, fish, and enjoy the magnificent ecosystem of the Great Barrier Reef.

For all its complexity, variety, and history, it is a remarkably fragile environment. In recent years, concern has grown that climate change associated with global warming and harmful influences of human use have become a serious and compounding threats to the reef. Both the living coral and the wondrous other creatures who occupy the reef are in jeopardy.

Geology and Geography

According to the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority, the current living reef structure is believed to have begun growing on an older platform about twenty thousand years ago when the sea level was about 130 meters (426 feet) lower than it is today.

From 20,000 years ago until 6,000 years ago, the sea level rose steadily. By around 13,000 years ago, the rising sea level was within 60 meters (196 feet) of its present level, and coral began to grow around the hills of the coastal plain, which by then were continental islands. As the sea level rose further still, most of the continental islands were submerged and the coral could then overgrow the hills, to form the present cays and reefs. Sea level on the Great Barrier Reef has not risen significantly in the last 6,000 years.

In the northern part of the Great Barrier Reef, ribbon reefs—long and thin and lacking a lagoon—and deltaic reefs resembling a river delta have formed; these reef structures are not found in the rest of the Great Barrier Reef system.

Species of the Great Barrier Reef

The Great Barrier Reef supports a variety of life, including many vulnerable or endangered species. Thirty species of whales, dolphins, and other porpoises have been recorded in the reef, including the dwarf minke whale, the Indo-Pacific humpback dolphin, and the humpback whale. Also, large populations of dugongs (herbivorous marine mammals similar to manatees) live there. Six species of sea turtle come to the reef to breed—green sea turtle, leatherback sea turtle, hawksbill turtle, loggerhead sea turtle, flatback turtle, and the olive ridley. The dugongs and sea turtles are attracted by the reef's 15 species of seagrass.

More than two hundred species of birds (including 40 species of water birds) live on the Great Barrier Reef, including the white-bellied sea eagle and roseate tern. Some five thousand species of mollusk have been recorded there, including the giant clam and various nudibranches and cone snails, as well as 17 species of sea snake. More than fifteen hundred species of fish live on the reef, including the clownfish, red bass, red-throat emperor, and several species of snapper and coral trout. Four hundred species of coral, both hard coral and soft coral, are found on the reef. Five hundred species of marine algae or seaweed live on the reef, along with the Irukandji jellyfish.

Environmental threats

Water quality

Unlike most reef environments worldwide, the Great Barrier Reef's water catchment area is home to both industrialized urban areas and extensive areas of coastal lands and rangelands used for agricultural and pastoral purposes.

The coastline of north eastern Australia has no major rivers, but it is home to several major urban centers including Cairns, Townsville, Mackay, Rockhampton, and the industrial city of Gladstone. Cairns and Townsville are the largest of these coastal cities with populations of approximately one hundred fifty thousand each.

Due to the range of human uses made of the water catchment area adjacent to the Great Barrier Reef, some 400 of the 3000 reefs are within a risk zone where water quality has declined owing to sediment and chemical runoff from farming, and to loss of coastal wetlands which are a natural filter. The principal agricultural activity is sugar cane farming in the wet tropics regions and cattle grazing in the dry tropics regions. Both are considered significant factors affecting water quality.

The members of GBRMPA believe that the mechanisms by which the poor water quality affects the reefs include increased competition by algae for the available light and oxygen and the enhancement of the spread of infectious diseases among the coral.[1] Also, copper, a common industrial pollutant in the waters of the Great Barrier Reef, has been shown to interfere with the development of coral polyps.[2]

Climate change

Some people believe that the most significant threat to the health of the Great Barrier Reef and of the planet's other tropical reef ecosystems is climate change effects occurring locally in the form of rising water temperatures and the El Niño effect. Many of the corals of the Great Barrier Reef are currently living at the upper edge of their temperature tolerance, as demonstrated in the coral bleaching events of the summers of 1998, 2002, and most recently 2006.[3]

Under the stress of waters that remain too warm for too long, corals expel their photosynthesising zooxanthellae and turn colorless, revealing their white, calcium carbonate skeletons. If the water does not cool within about a month, the coral will die. Australia experienced its warmest year on record in 2005. Abnormally high sea temperatures during the summer of 2005-2006 have caused massive coral bleaching in the Keppel Island group. A draft report by the UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change states that the Great Barrier Reef is at grave risk and could become "functionally extinct" by 2030, if indeed coral bleaching by then becomes an annual occurrence as many predict.[4]

Global warming may have triggered the collapse of reef ecosystems throughout the tropics. Increased global temperatures are thought by some scientists to bring more violent tropical storms, but reef systems are naturally resilient and recover from storm battering. While some scientists believe that an upward trend in temperature will cause much more coral bleaching, others suggest that while reefs may die in certain areas, other areas will become habitable for corals, and form coral reefs.[5][6] However, in their 2006 report, Woodford et al. suggest that the trend toward ocean acidification indicates that as the sea's pH decreases, corals will become less able to secrete calcium carbonate; and reef scientist Terry Done has predicted a one degree rise in global temperature would result in 82 percent of the reef bleached, two degrees resulting in 97 percent and three degrees resulting in "total devastation."[7]

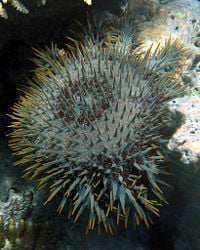

Crown-of-thorns starfish

The crown-of-thorns starfish is a coral reef predator that preys on coral polyps by climbing onto them, extruding the stomach over them, and releasing digestive enzymes to then absorb the liquefied tissue. An individual adult of this species can wipe out up to 19.6 square feet of living reef in a single year

Although large outbreaks of these starfish are believed to occur in natural cycles, human activity in and around the Great Barrier Reef can worsen the effects. Reduction of water quality associated with agriculture can cause the crown-of-thorns starfish larvae to thrive. Overfishing of its natural predators, such as the Giant Triton, is also considered to contribute to an increase in the number of crown-of-thorns starfish.

Overfishing

The unsustainable overfishing of keystone species, such as the giant triton, can cause disruption to the food chains that are vital to life on the reef. Fishing also impacts the reef through increased pollution from boats, by-catch of unwanted species, and reef habitat destruction from trawling, anchors, and nets. As of mid 2004, approximately one-third of the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park was protected from species removal of any kind, including fishing, without written permission.

Shipping

Shipping accidents are also a real concern, as several commercial shipping routes pass through the Great Barrier Reef. From 1985-2001, there were 11 collisions and 20 groundings on the inner Great Barrier Reef shipping route. The leading cause of shipping accidents in the Great Barrier Reef is human error.

Although the route through the Great Barrier Reef is not easy, reef pilots consider it safer than outside the reef in the event of mechanical failure, since a ship can sit safely in its protected waters while being repaired. On the outside, wind and swell will push a ship toward the reef and the water remains so deep right up to the reef, that anchoring is impossible.

Waste and foreign species discharged in ballast water from ships are a further biological hazard to the Great Barrier Reef. In addition, Tributyltin (TBT) compounds found in certain paints on ship hulls leach into seawater and are toxic to marine organisms as well as humans. Efforts are underway to restrict TBT use.

Oil

Oil drilling is not permitted on the Great Barrier Reef, yet oil spills are still considered one of the biggest threats to the reef, with a total of 282 oil spills from 1987-2002. It is believed that the reef may sit above a major natural oil reservoir. In the 1960s and early 1970s, there was some speculation about drilling for oil and gas there.

Human use

The Great Barrier Reef has long been utilized by indigenous Australian people, whose occupation of the continent is thought to extend back 40,000 to 60,000 years or more. For these approximately 70 clan groups, the reef is also an important part of their Dreamtime.

The Reef first became known to Europeans when the HMB Endeavour, captained by explorer James Cook, ran aground there on June 11, 1770, and experienced considerable damage. It was finally saved after lightening the ship as much as possible and re-floating it during an incoming tide.

Management

In 1975, the Government of Australia created the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park and defined what activities were prohibited on the Great Barrier Reef.[8] The park is managed, in partnership with the Government of Queensland, through the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority to ensure that it is widely understood and used in a sustainable manner. A combination of zoning, management plans, permits, education, and incentives (such as eco-tourism certification) are used in the effort to conserve the Great Barrier Reef.

In July 2004 a new zoning plan was brought into effect for the entire Marine Park, and has been widely acclaimed as a new global benchmark for the conservation of marine ecosystems. While protection across the Marine Park was improved, the highly protected zones increased from 4.5 percent to over 33.3 percent.

Tourism

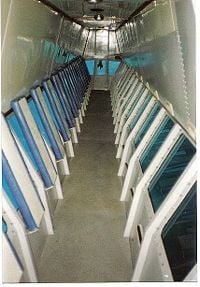

Due to its vast biodiversity, warm, clear waters, and its accessibility from the floating guest facilities called “live aboards,” the reef is a very popular destination for tourists, especially scuba divers. Many cities along the Queensland coast offer boat trips to the reef on a daily basis. Several continental islands have been turned into resorts.

As the largest commercial activity in the region, tourism in the Great Barrier Reef makes a significant contribution to the Australian economy. A study commissioned by the Australian Government and the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority The study estimates that the value-added economic contribution of the Great Barrier Reef World Heritage Area to the Australian economy in 2011-12 was $5.68 billion and it generated almost 69,000 full-time equivalent jobs.[9] There are approximately 2.43 million visitors to the Great Barrier Reef each year.[10] Although most of these visits are managed in partnership with the marine tourism industry, there are some very popular areas near shore (such as Green Island) that have suffered damage due to overfishing and land based run off.

A variety of boat tours and cruises are offered, from single day trips, to longer voyages. Boat sizes range from dinghies to superyachts. Glass-bottomed boats and underwater observatories are also popular, as are helicopter flights. But by far, the most popular tourist activities on the Great Barrier Reef are snorkeling and diving. Pontoons are often used for snorkeling and diving. When a pontoon is used, the area is often enclosed by nets. The outer part of the Great Barrier Reef is favored for such activities, due to water quality.

Management of tourism in the Great Barrier Reef is geared toward making tourism ecologically sustainable. A daily fee is levied that goes toward research of the Reef.

Fishing

The fishing industry in the Great Barrier Reef, controlled by the Queensland Government, is worth some 816 million dollars annually.[11] It employs approximately two thousand people, and fishing in the Great Barrier Reef is pursued commercially, recreationally, and traditionally, as a means of feeding one's family. Wonky holes (freshwater springs on the seabed) in the reef provide particularly productive fishing areas.

Notes

- ↑ GBRMPA, Great Barrier Reef Water Quality: Current Issues September 2001. Retrieved February 21, 2017.

- ↑ Emma Young, Copper decimates coral reef spawning, New Scientist. Retrieved February 21, 2017.

- ↑ GBRMPA, Coral bleaching Retrieved February 21, 2017.

- ↑ Michael Slezak, The Great Barrier Reef: a catastrophe laid bare The Guardian, June 6, 2016. Retrieved February 21, 2017.

- ↑ Greg Roberts, Great barrier grief as warm-water bleaching lingers. Retrieved February 21, 2017.

- ↑ Kate Ravilious, Coral reefs may grow with global warming. Retrieved February 21, 2017.

- ↑ J. Woodford, "Great? Barrier Reef," Australian Geographic 76 (2004): 37-55.

- ↑ Australasian Legal Information Institute, Reef Marine Park Act 1975. Retrieved February 21, 2017.

- ↑ Australian Government, Economic contribution of the Great Barrier Reef March 2013 Retrieved February 21, 2017.

- ↑ Great Barrier Reef tourist numbers. Retrieved February 21, 2017.

- ↑ GBRMPA, Measuring the economic and financial value of the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park. Retrieved February 21, 2017.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Doubilet, David. Great Barrier Reef (National Geographic Insight). National Geographic, 2002. ISBN 978-0792264750

- Mylne, Lee. Frommer's Portable Australia's Great Barrier Reef. Frommer's, 2007. ISBN 978-0764574344

- Zell, Len. Lonely Planet Diving & Snorkling the Great Barrier Reef. Lonely Planet Publications, 2006. ISBN 978-0864427632

External links

All links retrieved May 24, 2024.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.