Gustave Courbet

| Gustave Courbet | |

Gustave Courbet (portrait by Nadar). | |

| Birth name | Jean Désiré Gustave Courbet |

| Born | 06-10-1819 Ornans, France |

| Died | 1877-12-31 La Tour-de-Peilz, Switzerland |

| Nationality | French |

| Field | Painting, Sculpting |

| Training | Antoine-Jean Gros |

| Movement | Realism |

| Famous works | Burial at Ornans (1849-1850) L'Origine du monde (1866) |

Jean Désiré Gustave Courbet (June 10, 1819 – December 31, 1877) was a French painter whose portrayals of peasants and scenes of everyday life established him as the leading figure of the realist movement of the mid-nineteenth century.

Following the Revolution of 1848, his representation of contemporary social reality, his land and seascapes, and his female nudes were free of conventional idealism and embodied his rejection of the academic tradition. At the age of 28, he produced two paintings that are acclaimed as his best work: The Stone-Breakers and Burial at Ornans. With these paintings, Courbet secured a reputation as a radical whose departures from the prevailing tastes of Neoclassicism and Romanticism were offensive to contemporary art lovers.

Courbet was considered one of the most radical of all nineteenth-century painters and one of the fathers of modern art. He used his realistic paintings of peasants to promote his socialist view of the world. His political beliefs were influenced greatly by the life and the anarchist teachings of Pierre-Joseph Proudhon.

Early life

Gustave Courbet was born in the city of Ornans, on June 10, 1819. He grew up under the influence of his temperamental father, a prominent landowner. In 1831, Courbet began attending the Seminary in Ornans, where his own temperamental personality led to rebellious responses to religion and the clergy. When Courbet turned 18, he left home to pursue an education at the Collège Royal at Besançon.

At the Collège Royal traditional classical subjects were an anathema to Courbet and he encouraged students to revolt against tradition.

While studying at the college, Courbet made friends with the aspiring writer, Max Buchon. When Buchon's Essais Poétiques (1839) were being published, he commissioned Courbet to illustrate it. Courbet obliged by creating four beautiful lithographs for the work. Also during his studies, he enrolled as an externe, thus he could not only attend classes at the college, but he was also able to take classes from Charles Flajoulot at the école des Beaux-Arts.

Courbet left the college and moved to Paris in 1840. Here, he decided to begin an intense study of law, however he quickly changed his mind and realized that his true life's calling was painting. He spent hours upon hours copying various paintings in the Louvre. His first major breakthrough happened in 1844, with his painting, Self-Portrait with Black Dog. His painting was selected for a showing at the Salon.

Career

Between 1844 and 1847, Courbet traveled several times between Ornans and Paris and also Belgium and Holland. After coming into contact with J. van Wisselingh, a young art dealer in Amsterdam, who visited Paris and bought two of Courbet’s works and commissioned a self-portrait, Courbet's work was introduced to an appreciative audience outside of France. Van Wisselingh showed Courbet’s work to a rich collector in The Hague by the name of Hendrik Willem Mesdag, who purchased seven works. Mesdag was also the leader of The Hague School which was the most important artistic movement in Holland during the nineteenth century. Courbet’s work comprised an important part of what became the Mesdag Museum, currently in The Hague.[1]

In 1845, Courbet upped his submissions to the Salon with five paintings, however, only Le Guitarrero was selected. A year later all of his paintings were rejected. But in 1848, the Liberal Jury eased his anger, recognized his talent, and took all 10 of his entries. The harsh critic Champfleury apologized profusely to Courbet, praised his paintings, and began a friendship.

Courbet achieved artistic maturity with After Dinner at Ornans, which was shown at the Salon of 1849. His nine entries in the Salon of 1850 included the Portrait of Berlioz, the Man with the Pipe, the Return from the Fair, the Stone Breakers, and, largest of all, the Burial at Ornans, which contains over 40 life-size figures whose rugged features and static poses are reinforced by the somber landscape.

In 1851, the Second Empire was officially proclaimed, and during the next 20 years Courbet remained an uncompromising opponent of Emperor Napoleon III. At the Salon of 1853, where the painter exhibited three works, the Emperor pronounced one of them, The Bathers, obscene; nevertheless, it was purchased by a Montpellier innkeeper, Alfred Bruyas, who became the artist's patron and host. While visiting Bruyas in 1854, Courbet painted his first seascapes.

Of the 14 paintings Courbet submitted to the Paris World Exhibition of 1855, three major ones were rejected. In retaliation, he showed 40 of his pictures at a private pavilion he erected opposite the official one. That Courbet was ready and willing to stage an independent exhibition marks a turning point in the methods of artistic marketing, as single artist retrospective exhibitions were virtually unheard of. His method of self-promotion would later encourage other influential but reviled artists such as James McNeill Whistler.[2]

One of the rejected works from 1855 was the enormous painting The Studio, the full title of which was Real Allegory, Representing a Phase of Seven Years of My Life as a Painter. The work is filled with symbolism. At the center, between the two worlds expressed by the inhabitants of the left and right sides of the picture, is Courbet painting a landscape while a nude looks over his shoulder and a child admires his work. Champfleury found the notion of a "real allegory" ridiculous and concluded that Courbet had lost the conviction and simplicity of the earlier works.

Even though Courbet began to lose favor with some in his realist circle, his popular reputation, particularly outside France, was growing. He visited Frankfurt in 1858-1859, where he took part in elaborate hunting parties and painted a number of scenes based on direct observation. His Stag Drinking was exhibited in Besançon, where he won a medal, and in 1861 his work, as well as a lecture on his artistic principles, met with great success in Antwerp. In 1860 he submitted to the Salon La Roche Oraguay (Oraguay Rock) and four hunting scenes. Courbet received a second class medal, his third medal overall from the Salon jury.

Courbet's art of the mid-1860s no longer conveyed the democratic principles embodied in earlier works. He turned his attention increasingly to landscapes, portraits, and erotic nudes based, in part, on mythological themes. These include Venus and Psyche (1864; and a variant entitled The Awakening), Sleeping Women, The Origin of the World (1866), and Woman with a Parrot (1866).

In 1865, his series depicting storms at sea astounded the art world and opened the way for Impressionism.

Realism

Gustave Courbet is often given credit for coining the term realism. He was innovative in the movements creation, his art fed its rapid growth, and several other artists were soon dubbing themselves "realists."

His art traversed the topics of peasant life, poor working conditions, and abject poverty. Because of his attention to such subject matter, Courbet never quite fit into the other artistic categories of Romanticism or Neoclassicism. Courbet felt that these schools of art were not concerned with the pursuit of truth. He believed that if his paintings could realistically and truthfully capture the social imbalances and contradictions he saw, then it would spur people to action.

Speaking about his philosophy Courbet wrote, "The basis of realism is the negation of the ideal, a negation towards which my studies have led me for 15 years and which no artist has dared to affirm categorically until now."[3]

He strove to achieve an honest imagery of the lives of simple people, but the monumentality of the concept in conjunction with the rustic subject matter proved to be widely unacceptable. Art critics and the public preferred pretty pictures so the notion of Courbet's "vulgarity" became popular as the press began to lampoon his pictures and criticize his penchant for the ugly.

Burial at Ornans

The Burial at Ornans has long been considered Courbet's greatest work. He recorded an event which he witnessed during the fall of 1848, the funeral of his grand uncle. Artists before him who painted real events often used models in recreating the scene. But Courbet, true to his calling as a realist, said that he "painted the very people who had been present at the interment, all the townspeople." This painting became the first realistic presentation of the townspeople and their way of life in Ornans.

The painting was enormous. It measured 10 by 22 feet (3.1 by 6.6 meters) and portrayed something that was thought prosaic and dull: A simple funeral. But viewers were even more upset because paintings of this size were only ever used to depict royalty or religion. With the birth of this painting, Courbet said, "The Burial at Ornans was in reality the burial of Romanticism."[4]

Notoriety

In 1870, at the height of his career, he was drawn directly into political activity. After the fall of the Second Empire, Courbet was elected President of the Federation of Artists. a group that promoted the uncensored production and expansion of art. The group's members included André Gill, Honoré Daumier, Jean-Baptiste Camille Corot, Eugène Pottier, Jules Dalou, and Édouard Manet.

Courbet stayed in Paris while it was besieged by the Prussian armies, and when many were fleeing the capital. During this time, Courbet refused the Cross of the Legion of Honor, just as Daumier, another Realist artist, had. Despite his refusal of the honor, the new Commune government appointed Courbet Chairman of the Arts Commission, whose sole duty was to protect the works of art in Paris from the Prussian siege.

While serving as Chairman it was decided that the hated Vendôme Column, that represented imperialism of Napoleon Bonaparte would be taken down by dismantlement. The Commune was short-lived, however, and in May of 1871, mass executions began and all Commune leaders, such as Courbet, were either executed or jailed.

Courbet managed to escape by keeping a low profile, but on June 7, he was arrested and interrogated, later thrown in the Conciergerie, where many were imprisoned during the French Revolution. His trial was in August, and in September he was sentenced to six months in prison. It was also determined by the newly elected president that Courbet was responsible for the reconstruction of the Vendome Column. With a price of over three hundred thousand francs set it was impossible for him to pay. On July 23, 1873, Courbet, through the assistance of a few friends, fled France for Switzerland.

Le Château de Chillon (1874), depicting a picturesque medieval castle that was a symbol of isolation and imprisonment was among the last paintings he made before his death.

Courbet stayed in Switzerland for four years where he died as an exile on December 31, 1877.

In the preface to the catalog for the posthumous Courbet exhibition held at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in 1882, Jules Castagnary said, "If Courbet could only paint what he saw, he saw wonderfully, he saw better than anybody else."[5]

Legacy

Gustave Courbet was influential in many regards. First, he broke the mold of convention with his revolutionary ideas and techniques. This, in turn, lead to the creation of a new art movement, that of Realism. This important contribution to the world of art opened the path for many to follow. During the 1860s, Paul Cezanne took up Courbet's technique of painting with a palette knife, as well as his dark colors and layers of thick paint. He is often credited with inspiring the Impressionist painters, in particular Edouard Manet (the father of Impressionism).[6] Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841-1919) was also influenced by Courbet in his early career, before taking his own direction, and Courbet's nudes had a lasting influence on him.[7]

His hostility to the academic system, state patronage and the notion of aesthetic ideals also made him highly influential in the development of modernism. Courbet also transformed traditional oil painting with his innovative use of tools, especially palette knives, and also rags, sponges, and even his fingers. These new approaches laid the groundwork for a vital strain of modernist painting.[8]

On June 28, 2007, Courbet’s Femme Nue sold to an anonymous bidder for $2.04 million. It was a new record for one of his paintings.[9] In October 2007, Courbet’s Le Veau Blanc (1873), a painting of a brown-spotted white heifer looking out at the viewer as it stops to drink from a stream, sold to an anonymous buyer for $2,505,000, setting yet another record.[10]

His works hang in galleries throughout the world. The Metropolitan Museum of Art has more than twenty of his works.

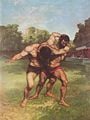

Gallery

Notes

- ↑ Rehs.com, Gustave Courbet. Retrieved December 15, 2007.

- ↑ Rehs.com, Gustave Courbet. Retrieved December 15, 2007.

- ↑ Gerstle Mack, Gustave Courbet (Da Capo, 1989). ISBN 0306803755

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Musee-orsay.fr, Reception of Courbet's Work. Retrieved December 15, 2007.

- ↑ Redflag.org.uk, Gustave Courbet and Realism. Retrieved November 28, 2007.

- ↑ Musee-orsay.fr, Courbet Biography. Retrieved December 15, 2007.

- ↑ Getty.edu, the Getty Announces Major Tour of Gustave Courbet's Pivotal Landscapes.

- ↑ Sgallery.net, Record for Gustav Bauernfeind Set—GBP3 Million.

- ↑ Art Net, Muscle at October Auctions. Retrieved December 14, 2007.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Chu, Petra ten-Doesschate. The Most Arrogant Man in France: Gustave Courbet and the Nineteenth Century Media Culture. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2007. ISBN 0691126798

- Clark, T. J. Image of the People: Gustave Courbet and the 1848 Revolution. London: Thames & Hudson, 1999. ISBN 050027245X

- Courbet, Gustave, Leon Wieseltier, and Sarah Faunce. Gustave Courbet. New York: Salander-O'Reilly, 2003. ISBN 158821124X

- Faunce, Sarah, Gustave Courbet, and Linda Nochlin. Courbet Reconsidered. Brooklyn: Brooklyn Museum, 1988. ISBN 0300042981

- Fried, Michael. Courbet's Realism. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1990. ISBN 0226262146

- Nochlin, Linda. Courbet. London: Thames & Hudson, 2007. ISBN 0500286760

- Nochlin, Linda. Realism. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1971. ISBN 0140213058

- This article incorporates text from the Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition, a publication now in the public domain.

External links

All links retrieved June 21, 2024.

- Gustave Courbet Rehs.com.

- Gustave Courbet Artrenewal.org.

- Gustave Courbet Artcyclopedia.com.

- Gustave Courbet Ibiblio.org.

- Reception of Courbet's Work Musee-orsay.fr.

- Kimmelman, Michael. 1988. Critic's Notebook; Ever-Provocative Courbet Examined Anew Query.nytimes.com.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.