Health

Health is a term that refers to a combination of the absence of illness, the ability to manage stress effectively, good nutrition and physical fitness, and high quality of life.

In any organism, health can be said to be a "state of balance," or analogous to homeostasis, and it also implies good prospects for continued survival.

A widely accepted definition is that of the World Health Organization (WHO), the United Nations body that sets standards and provides global surveillance of disease. In its constitution, the WHO states that "health is a state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity." In more recent years, this statement has been modified to include the ability to lead a "socially and economically productive life."

The WHO definition is not without criticism, as some argue that health cannot be defined as a state at all, but must be seen as a process of continuous adjustment to the changing demands of living and of the changing meanings we give to life. The WHO definition is therefore considered by many as an idealistic goal rather than a realistic proposition.

Beginning in the 1950s with Halbert L. Dunn, and continuing in the 1970s with Donald B. Ardell, John Travis, Robert Allen and others, optimal health was given a broader, more inclusive interpretation called "wellness."

Health is often monitored and sometimes maintained through the science of medicine, but can also be improved by individual health and wellness efforts, such as physical fitness, good nutrition, stress management, and good human relationships. Personal and social responsibility (those with means helping those without means) are fundamental contributors to maintenance of good health. (See health maintenance below).

In addition to the focus on individual choices and lifestyles related to health, other key areas of health include environmental health, mental health, population health, and public health.

Wellness

According to Dr. Donald B. Ardell, author of the best seller “High Level Wellness: An Alternative To Doctors, Drugs and Disease” (1986) and publisher of the Ardell Wellness Report, “wellness is first and foremost a choice to assume responsibility for the quality of your life. It begins with a conscious decision to shape a healthy lifestyle. Wellness is a mindset, a predisposition to adopt a series of key principles in varied life areas that lead to high levels of well-being and life satisfaction.”

Many wellness promoters like Ardell see wellness as a philosophy that embraces many principles for good health. The areas most closely affected by one’s wellness commitments include self-responsibility, exercise and fitness, nutrition, stress management, critical thinking, meaning and purpose or spirituality, emotional intelligence, humor and play, and effective relationships.

Health maintenance

Physical fitness, healthy eating, stress management, a healthy environment, enjoyable work, and good human relationship skills are examples of steps to improve one's health and wellness.

Physical fitness has been shown to reduce the risk of dying prematurely, developing heart disease, diabetes, high blood pressure, and colon cancer. It has also been shown to reduce feelings of anxiety and depression, control weight, and help improve overall psychological well-being.

Healthy eating has been linked to the prevention and treatment of many diseases, especially cancer, heart disease, hypoglycemia, and diabetes. Overall, people with healthy eating habits feel better, keep up strength and energy, manage weight, tolerate treatment-related side effects, decrease the risk of infection, and heal and recover more quickly. Studies have also shown a correlation between persons with a hypoglycemia and crime. For persons with adult onset diabetes, in some cases healthy eating can reduce or eliminate the need for insulin.

Researchers have long known that stress management can help people reduce tension, anxiety, and depression, as well as help people cope with life challenges more effectively. Stress management can also assist persons in having more satisfying human relationships, job satisfaction and a sense of life purpose. Duke University Medical Center researchers have recently found that stress may also provide cardiovascular health as well.

A good environment that has clean and safe drinking water, clean air, is relatively free of toxic elements, and not overcrowded, can increase life expectancy significantly. Environmental Health is becoming an increasingly important consideration for causes of premature death.

Wellness workplace programs are recognized by an increasingly large number of companies for their value in improving health and well-being of their employees, and increasing morale, loyalty, and productivity at work. A company may provide a gym with exercise equipment, start smoking cessation programs, and provide nutrition, weight, or stress management training. Other programs may include health risk assessments, safety and accident prevention, and health screenings. Some workplaces are working together to promote entire healthy communities. One example is through the Wellness Council of America.[1]

Environmental health

Environmental health comprises those aspects of human health, including quality of life, that are determined by physical, chemical, biological, social, and psychosocial factors in the environment. It also refers to the theory and practice of assessing, correcting, controlling, and preventing those factors in the environment that can potentially affect adversely the health of present and future generations[2]

Environmental health, as used by the WHO Regional Office for Europe, includes both the direct pathological effects of chemicals, radiation, and some biological agents, and the effects (often indirect) on health and wellbeing of the broad physical, psychological, social, and aesthetic environment, which includes housing, urban development, land use, and transport.

Nutrition, soil contamination, water pollution, air pollution, light pollution, waste control, and public health are integral aspects of environmental health.

In the United States, the Center for Disease Control Environmental Health programs include: air quality, bioterrorism, environmental hazards and exposure, food safety, hazardous substances, herbicides, hydrocarbons, lead, natural disasters, pesticides, smoking and tobacco use, water quality, and urban planning for healthy places.[3]

While lifestyles have been by far the leading factor in premature deaths, environmental factors is the second leading cause and has been increasing in its importance for health over the past several decades.

Environmental health services are defined by the World Health Organization as:

those services that implement environmental health policies through monitoring and control activities. They also carry out that role by promoting the improvement of environmental parameters and by encouraging the use of environmentally friendly and healthy technologies and behaviors. They also have a leading role in developing and suggesting new policy areas.

The Environmental Health profession had its modern-day roots in the sanitary and public health movement of the United Kingdom. This was epitomized by Sir Edwin Chadwick, who was instrumental in the repeal of the poor laws and was the founding president of the Chartered Institute of Environmental Health.

Mental health

Mental health is a concept that refers to a human individual's emotional and psychological well-being. The Merriam-Webster dictionary defines mental health as "A state of emotional and psychological well-being in which an individual is able to use his or her cognitive and emotional capabilities, function in society, and meet the ordinary demands of everyday life."

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), there is no one "official" definition of mental health:

Mental health has been defined variously by scholars from different cultures. Concepts of mental health include subjective well-being, perceived self-efficacy, autonomy, competence, intergenerational dependence, and self-actualization of one's intellectual and emotional potential, among others. From a cross-cultural perspective, it is nearly impossible to define mental health comprehensively. It is, however, generally agreed that mental health is broader than a lack of mental disorders.[4]

Cultural differences, subjective assessments, and competing professional theories all affect how "mental health" is defined. In general, most experts agree that "mental health" and "mental illness" are not opposites. In other words, the absence of a recognized mental disorder is not necessarily an indicator of mental health.

One way to think about mental health is by looking at how effectively and successfully a person functions. Feeling capable and competent, being able to handle normal levels of stress, maintaining satisfying relationships, leading an independent life, and being able to "bounce back," or recover from difficult situations are all signs of mental health.

Mental health, as defined by the U.S. Surgeon General's Report on Mental Health, "refers to the successful performance of mental function, resulting in productive activities, fulfilling relationships with other people, and the ability to adapt to change and cope with adversity."

Some experts consider mental health as a continuum with the other end of the continuum being mental disorders. Thus, an individual's mental health may have many different possible values. Mental wellness is generally viewed as a positive attribute, such that a person can reach enhanced levels of mental health, even if they do not have any diagnosable mental illness. This definition of mental health highlights emotional well being as the capacity to live a full and creative life, with the flexibility to deal with life's inevitable challenges. Some mental health experts and health and wellness promoters are now identifying the capability for critical thinking as a key attribute of mental health as well. Many therapeutic systems and self-help books offer methods and philosophies espousing presumably effective strategies and techniques for further improving the mental wellness of otherwise healthy people.

Population health

Population health is an approach to health that aims to improve the health of an entire population. One major step in achieving this aim is to reduce health inequities among population groups. Population health seeks to step beyond the individual-level focus of mainstream medicine and public health by addressing a broad range of factors that impact health on a population-level, such as environment, social structure, resource distribution, and so forth.

Population health reflects a shift in thinking about health as it is usually defined. Population health recognizes that health is a resource and a potential as opposed to a static state. It includes the potential to pursue one’s goals to acquire skills and education and to grow.

An important theme in population health is importance of social determinants of health and the relatively minor impact that medicine and healthcare have on improving health overall. From a population health perspective, health has been defined not simply as a state free from disease but as "the capacity of people to adapt to, respond to, or control life's challenges and changes."[5]

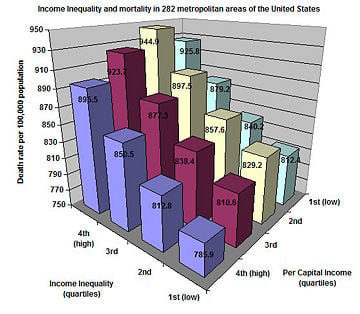

Recently, there has been increasing interest from epidemiologists on the subject of economic inequality and its relation to the health of populations. There is a very robust correlation between socioeconomic status and health. This correlation suggests that it is not only the poor who tend to be sick when everyone else is healthy, but that there is a continual gradient, from the top to the bottom of the socioeconomic ladder, relating status to health. This phenomenon is often called the "SES Gradient." Lower socioeconomic status has been linked to chronic stress, heart disease, ulcers, type 2 diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, certain types of cancer, and premature aging.

Population health parameters indicate, for example, that the economic inequality within the United States is a factor that explains why the United States ranks only 30th in life expectancy, right behind Cuba. which is 29th. All 29 countries that rank better than the United States have a much smaller gap of income distribution between their richest and poorest citizens.

Despite the reality of the SES Gradient, there is debate as to its cause. A number of researchers (A. Leigh, C. Jencks, A. Clarkwest) see a definite link between economic status and mortality due to the greater economic resources of the better-off, but they find little correlation due to social status differences. Other researchers (such as R. Wilkinson, J. Lynch, and G. A. Kaplan) have found that socioeconomic status strongly affects health even when controlling for economic resources and access to health care.

Most famous for linking social status with health are the Whitehall studies—a series of studies conducted on civil servants in London. The studies found that, despite the fact that all civil servants in England have the same access to health care, there was a strong correlation between social status and health. The studies found that this relationship stayed strong even when controlling for health-effecting habits such as exercise, smoking, and drinking. Furthermore, it has been noted that no amount of medical attention will help decrease the likelihood of someone getting type 1 diabetes or rheumatoid arthritis—yet both are more common among populations with lower socioeconomic status. Lastly, it has been found that among the wealthiest quarter of countries on earth (a set stretching from Luxembourg to Slovakia), there is no relation between a country's wealth and general population health, suggesting that past a certain level, absolute levels of wealth have little impact on population health, but relative levels within a country do.[6]

The concept of psychosocial stress attempts to explain how psychosocial phenomenon such as status and social stratification can lead to the many diseases associated with the SES Gradient. Higher levels of economic inequality tend to intensify social hierarchies and generally degrades the quality of social relations, leading to greater levels of stress and stress related diseases. Wilkinson found this to be true not only for the poorest members of society, but also for the wealthiest. Economic inequality is bad for everyone's health.

Inequality does not affect only the health of human populations. D. H. Abbott at the Wisconsin National Primate Research Center found that among many primate species, those with less egalitarian social structures correlated with higher levels of stress hormones among socially subordinate individuals. Research by R. Sapolsky of Stanford University provides similar findings.

Public health

Public health is concerned with threats to the overall health of a community based on population health analysis.

The size of the population in question can be limited to a dozen or less individuals, or, in the case of a pandemic, whole continents. Public health has many sub-fields, but is typically divided into the categories of epidemiology, biostatistics, and health services. Environmental, social and behavioral health, and occupational health are also important fields in public health.

The focus of a public health intervention is to prevent, rather than treat a disease, through surveillance of cases and the promotion of healthy behaviors. In addition to these activities, in many cases treating a disease can be vital to preventing it in others, such as during an outbreak of an infectious disease such as HIV/AIDS. Vaccination programs, distribution of condoms, and promotion of abstinence or fidelity in marriage are examples of public health measures advanced in various countries.

Many countries have their own government agencies, sometimes known as ministries of health, to respond to domestic health issues. In the United States, the frontline of public health initiatives are state and local health departments. The Surgeon General-led United States Public Health Service, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in Atlanta, Georgia, although based in the United States, are also involved with several international health issues in addition to their national duties.

All of the areas of health, including individual health and wellness, environmental health, mental health, population health, and public health now need to be viewed in a global context. In a global society, the health of every human being is relevant to the health of each one of us. For example, a disease outbreak in one part of the world can quickly travel to other regions and continents, via international travel, creating a global problem.

Global health requires that the world’s citizens collaborate to improve all types of health in all nations, rich or poor, and seek to prevent, reduce, and stop disease outbreaks at their source.

Notes

- ↑ Wellness Council of America. Retrieved March 18, 2020.

- ↑ Public Health, Environmental and Social Determinants of Health. World Health Organization. Retrieved March 18, 2020.

- ↑ Environmental Health Center for Disease Control.

- ↑ World Health Organization, Chapter 1: A public health approach to mental health: Understanding mental health. The world health report . Retrieved March 18, 2020.

- ↑ C.J. Frankish, et al., Health Impact Assessment as a Tool for Population Health Promotion and Public Policy. University of British Columbia, Vancouver: Institute of Health Promotion Research, 1996.

- ↑ Erin Wigger, The Whitehall Study The Center For Social Epidemiology. Retrieved March 18, 2020.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Ardell, D.B. The History and Future of Wellness. Dubuque, IA: Kendall Hunt, 1983.

- Ardell, D.B. High Level Wellness: An Alternative to Doctors, Drugs and Disease. Berkeley, CA: Ten Speed Press, 1986.

- Ardell, D.B. The Book of Wellness: A Secular Approach to Spirituality, Meaning & Purpose. Amherst, NY: Prometheus Books, 1996.

- Breslow, L. (ed.). Encyclopedia of Public Health. Macmillan Reference, 2002.

- Chin, J.B. (ed.). Control of Communicable Diseases Manual, 17th Edition. Washington, DC: American Public Health Association, 2000. ISBN 0875531822.

- Frankish, C.J., et al. Health Impact Assessment as a Tool for Population Health Promotion and Public Policy. University of British Columbia, Vancouver: Institute of Health Promotion Research, 1996.

- Ryan, R.S., and J. Travis. Wellness: Small Changes You Can Use to Make a Big Difference. Berkeley, CA: Ten Speed Press, 1991.

- Wilkinson, R., and M. Marmot. The Solid Facts: Social Determinants of Health. World Health Organization, 2003.

- World Health Organization (WHO). Constitution, World Health Organization, October 2006. Retrieved March 18, 2020.

- World Health Organization (WHO). Health for All Series, No.1 and No. 2. Geneva: World Health Organization, 1979.

External links

All links retrieved June 25, 2024.

- World Health Organization

- National Center for Health Statistics (USA)

- National Institutes of Health (USA)

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (USA)

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

- Health history

- Environmental_health history

- Mental_health history

- Population_health history

- Public_health history

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.