Heinrich Schliemann

Johann Ludwig Heinrich Julius Schliemann (January 6, 1822 â December 26, 1890) was a German businessman and classical archaeologist, an advocate of the historical reality of places mentioned in the works of Homer, and an important excavator of the Mycenaean sites of Troy, Mycenae, and Tiryns. Although he was untrained in archaeological techniques and was more of a "treasure-hunter" than a scientist, his enthusiasm and determination led him to many significant finds. His work inspired other trained archaeologists to continue the search for people and places recorded only in myth and legend, and brought new recognition to the lives of those who formed the early history of humankind.

Born in Germany, losing his mother when he was 9, and having his classical education terminated at age 14 when his father lost his income after being accused of embezzlement, Schliemann possessed a genius for language and a business acumen that permitted him to establish profitable businessesâin California during the Gold Rush days and later in Russia. He thereby acquired sufficient wealth that he could pursue his passion for ancient Greek cities and treasures. Though he sought professional recognition, it eluded him, not only because of his lack of formal education, but also because of his low ethical and scientific standards.

Early life

Johann Ludwig Heinrich Julius Schliemann was born on January 6, 1822, at Neubuckow, in Mecklenburg-Schwerin, Germany, to Ernst Schliemann, a Protestant minister, and Luise Therese Sophie. In 1831, when he was nine, his mother died. There is no question that this was a traumatic event for him (later in life he developed a fetish for women named Sophie). Heinrich was sent to live with his uncle.

He enrolled in the gymnasium (grammar school) at Neustrelitz at age 11. His attendance was paid for by his father. He was there for at least a year. Later he claimed that, as a boy, his interest in history was encouraged by his father, who, he said, had schooled him in the tales of the Iliad and the Odyssey and had given him a copy of Ludwig Jerrer's Illustrated History of the World for Christmas 1829. Schliemann also later claimed that at the age of eight he declared he would one day excavate the city of Troy.

It is unknown whether his childhood interest in and connection with the classics continued during his time at the gymnasium, but it is likely that he would have been further exposed to Homer. It may be that he had just enough of a classical education to endow him with a yearning for it, when it was snatched from him: he was transferred to the vocational school, or Realschule, after his father was accused of embezzling church funds in 1836, and so could not afford to pay for the gymnasium.

According to Schliemannâs diary, his interest in ancient Greece was sparked when he overheard a drunken university student reciting the Odyssey of Homer in classical Greek and he was taken by the language's beauty. The accuracy of that information, along with many details in his diaries, however, is considered doubtful because of a pattern of prevarication that seems to have run through his life. One example is the fact that he was found to have forged documents to divorce his wife and lied in order to obtain U.S. citizenship.

Prevarication and a longing to return to the educated life and reacquire all the things of which he was deprived in childhood are thought by many to have been a common thread in Schliemann's life. In his archaeological career, there was always a gulf separating Schliemann from the educated professionals; a gulf deepened by his tendency to pose as something he was not and at the same time a gulf that impelled him in his posing.

After leaving the Realschule, Heinrich became a grocer's apprentice at age fourteen, for Herr Holtz's grocery in Furstenburg. He labored in the grocery for five years, reading voraciously whenever he had a spare moment. In 1841, Schliemann fled to Hamburg and became a cabin boy on the Dorothea, a steamship bound for Venezuela. After twelve days at sea, the ship foundered in a gale, and the survivors washed up on the shores of the Netherlands.

Career as a businessman

After the shipwreck, Schliemann underwent a brief period of being footloose in Amsterdam and Hamburg, at age 19. This circumstance came to an end with his employment, in 1842, at the commodities firm of F. C. Quien and Son. He became a messenger, office attendant, and then bookkeeper there.

On March 1, 1844, he changed jobs, going to work for B. H. Schröder & Co., an import/export firm. There he showed such judgment and talent for the work that they appointed him as a general agent in 1846 to St. Petersburg, Russia. There, the markets were favorable and he represented a number of companies. Schliemann prospered, but how well is not known. In view of his experiences with his first wife, he probably did not become rich at that time. He did learn Russian and Greek, employing a system that he used his entire life to learn languagesâhe wrote his diary in the language of whatever country he happened to be in.

Schliemann had a gift for languages and by the end of his life he was conversant in English, French, Dutch, Spanish, Portuguese, Swedish, Italian, Greek, Latin, Russian, Arabic and Turkish as well as his native German. Schliemann's ability with languages was an important part of his career as a businessman in the import trade.

In 1850, he learned of the death of his brother, Ludwig, who had become wealthy as a speculator in the California gold fields. Seeing the opportunity, Schliemann went to California in early 1851, and started a bank in Sacramento. The bank bought and resold over a million dollars in gold dust in just six months. The prospectors could mine or pan for the gold, but they had no way to sell it except to middlemen such as Schliemann, who made quick fortunes.

Later, Schliemann claimed to have acquired United States citizenship when California was made a state. According to his memoirs, before arriving in California he had dined in Washington with President Millard Fillmore and family. He also wrote an account of the San Francisco fire of 1851.

He did not remain in the United States long. On April 7, 1852, he sold his business rather suddenly (due to fever he said) and returned to Russia. There, he attempted to live the life of a gentleman, which brought him into contact with Ekaterina Lyschin, the niece of one of his wealthy friends. He was now 30 years of age.

Heinrich and Ekaterina were married on October 12, 1852. The marriage was troubled from the start. Ekaterina wanted him to be richer than he was and withheld conjugal rights until he made a move in that direction, which he finally did. The canny Schliemann cornered the market in indigo and then went into the indigo business, turning a good profit. This move won him Ekaterina's intimacy and they had a son, Sergey. Two other children followed.

Having a family to support led Schliemann to tend to business. He found a way to make yet another quick fortune as a military contractor in the Crimean War, from 1854 to 1856. He cornered the market in saltpeter, brimstone, and lead, all constituents of ammunition, and resold them to the Russian government.

By 1858, Schliemann was as wealthy as ever a man could wish. The poor minister's son had overcome poverty in his own life. However, he refused to haunt the halls of trade and speculation. He was not a professional businessman, and was no longer interested in speculation. Therefore, he retired from business to pursue other interests. In his memoirs he claimed he wished to dedicate himself to the pursuit of Troy, but the truth of this claim, along with numerous others, is questioned by many.

Career as an archeologist

It is not certain by what path Schliemann really did arrive at archaeology or Troy. He traveled a great deal, seeking out ways to link his name to famous cultural and historical icons. One of his most famous exploits was disguising himself as a Bedouin tribesman to gain access to forbidden areas of Mecca.

His first interest of a classical nature seems to have been the location of Troy whose very existence was at that time in dispute. Perhaps his attention was attracted by the first excavations at Santorini in 1862 by Ferdinand Fouqué. On the other hand, he may have been inspired by Frank Calvert, whom he met on his first visit to the Hisarlik site in 1868.

Somewhere in his many travels and adventures he lost Ekaterina. She was not interested in adventure and remained in Russia. Schliemann, claiming to have become a U.S. citizen in 1850, utilized the divorce laws of Indiana to divorce Ekaterina in absentia.

Based on the work of a British archeologist, Frank Calvert, who had been excavating the site in Turkey for over 20 years, Schliemann decided that Hisarlik was the site of Troy. In 1868, Schliemann visited sites in the Greek world, published Ithaka, der Peloponnesus und Troja in which he advocated for Hisarlik as the site of Troy, and submitted a dissertation in ancient Greek proposing the same thesis to the University of Rostock. He later claimed to have received a degree from Rostock by that submission.

In 1868, regardless of his previous interests and adventures, or the paths by which he arrived at that year, Schliemann's course was set. He took over Calvert's excavations on the eastern half of the Hisarlik site, which was on Calvert's property. The Turkish government owned the western half. Calvert became Schliemann's collaborator and partner.

Schliemann brought dedication, enthusiasm, conviction, and a not inconsiderable fortune to the work. Excavations cannot be made without funds, and are in vain without publication of the results. Schliemann was able to provide both. Consequently, he dominated the field of Mycenaean archaeology in his lifetime, and, despite his many faults, still commands the loyalty of classical archaeologists, perhaps deservedly so.

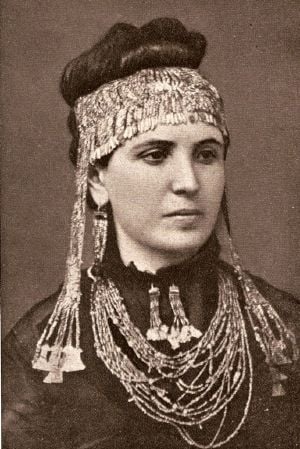

Schliemann knew he would need an "insider" collaborator versed in Greek culture of the times. As he had just divorced Ekaterina, he was in a position to advertise for a wife, which he did, in the Athens newspaper. His friend, the Archbishop of Athens, suggested a relative of his, the seventeen-year-old Sophia Engastromenos. As she fit the qualifications, he married her almost at once (1869). They later had two children, Andromache and Agamemnon Schliemann. He reluctantly allowed them to be baptized, and solemnized the ceremony by placing a copy of the Iliad on the children's heads and reciting a hundred hexameters.

By 1871, Schliemann was ready to go to work at Troy. Thinking that Homeric Troy must be in the lowest level, he dug hastily through the upper levels, reaching fortifications that he took to be his target. In 1872, he and Calvert clashed over this method. Schliemann flew into a fury when Calvert published an article stating that the Trojan War period was missing from the record, implying that Schliemann had destroyed it.

As if to exonerate his views, a cache of gold suddenly appeared in 1873, which Schliemann dubbed "Priam's Treasure." According to him, he saw the gold glinting in the dirt and dismissed the workmen so that he and Sophie could personally excavate it and remove it in Sophie's shawl. Sophie wore one item, the "Jewels of Helen," for the public. He published his findings in Trojanische AltertĂŒmer, 1874.

This publicity stunt backfired when the Turkish government revoked his permission to dig and sued him for a share of the gold. Collaborating with Calvert, he had smuggled the treasure out of Turkey, which did not endear him to the Turkish authorities. This was not the first time Calvert and Schliemann had smuggled antiquities. Such behavior contributed toward bad relations with other nations, which extended into the future. (Priam's Treasure remains the object of an international tug-of-war.)

Meanwhile, Schliemann published Troja und seine Ruinen in 1875 and excavated the Treasury of Minyas at Orchomenos. In 1876, he began excavating at Mycenae. Discovering the Shaft Graves with their skeletons and more regal gold, such as the Mask of Agamemnon, the irrepressible Schliemann cabled the king of Greece. The results were published in Mykena (1878).

Although he had received permission to excavate in 1876, Schliemann did not reopen the dig at Troy until 1878â1879, after another excavation in Ithaca designed to locate the actual sites of the Odysseus story. Emile Burnouf and Rudolph Virchow joined him in 1879 for his second excavation of Troy. There was a third excavation, 1882â1883, an excavation of Tiryns in 1884 with Wilhelm Dörpfeld, and a fourth at Troy, 1888â1890, with Dörpfeld, who taught him stratigraphy. By then, however, much of the site had been lost to unscientific digging.

Decline and death

On August 1, 1890, Schliemann returned to Athens, and in November traveled to Halle for an operation on his chronically infected ears. The doctors dubbed the operation a success, but his inner ear became painfully inflamed. Ignoring his doctors' advice, he left the hospital and traveled to Leipzig, Berlin, and Paris. From Paris, he planned to return to Athens in time for Christmas, but his ears became even worse. Too sick to make the boat ride from Naples to Greece, Schliemann remained in Naples, but managed to make a journey to the ruins of Pompeii. On Christmas day he collapsed in Naples and died in a hotel room on December 26, 1890. His corpse was then transported by friends to Athens. It was then interred in a mausoleum, a temple he erected for himself. The inscription above the entrance, that he had created in advance, read: For the Hero, Schliemann.

Criticism

Schliemann's career began before archaeology developed as a professional field, and so, by present standards, the field technique of Schliemann's work was at best "amateurish." Indeed, further excavation of the Troy site by others has indicated that the level he named the Troy of the Iliad was not that. In fact, all of the materials given Homeric names by Schliemann are considered of a pseudo- nature, although they retain the names. His excavations were even condemned by the archaeologists of his time as having destroyed the main layers of the real Troy. They were forgetting that, before Schliemann, not many people even believed in a real Troy.

One of the main problems of his work is that "King Priam's Treasure" was putatively found in the Troy II level, of the primitive Early Bronze Age, long before Priam's city of Troy VI or Troy VIIa in the prosperous and elaborate Mycenaean Age. Moreover, the finds were unique. These unique and elaborate gold artifacts do not appear to belong to the Early Bronze Age.

In the 1960s, William Niederland, a psychoanalyst, conducted a psychobiography of Schliemann to account for his unconscious motives. Niederland read thousands of Schliemann's letters and found that he hated his father and blamed him for his mother's death, as evidenced by vituperative letters to his sisters. This view seems to contradict the loving image Schliemann gave, and calls the entire childhood dedication to Homer into question. Nothing in the early letters indicates that that the young Heinrich was even interested in Troy or classical archaeology.

Niederland concluded that Schliemann's preoccupation (as he saw it) with graves and the dead reflected grief over the loss of his mother, for which he blamed his father, and his efforts at resurrecting the Homeric dead represent a restoration of his mother. Whether this sort of evaluation is valid is debatable. However, it raised serious questions about the truthfulness of Schliemann's accounts of his life.

In 1972, William Calder of the University of Colorado, speaking at a commemoration of Schliemann's birthday, revealed that he had uncovered several untruths. Other investigators followed, such as David Traill of the University of California. Some of their findings were:

- Schliemann claimed in his memoirs to have dined with President Millard Fillmore in the White House in 1850. However newspapers of the day made no mention of such a meeting, and it seems unlikely that the president of the United States would have a desire to spend time with a poor immigrant. Schliemann left California hastily in order to escape from his business partner, whom he had cheated.

- Schliemann did not become a U.S. citizen in 1850 as he claimed. He was granted citizenship in New York City in 1868 on the basis of his false claim that he had been a long-time resident. He did divorce Ekaterina from Indiana, in 1868.

- He never received any degree from the University of Rostock, which rejected his application and thesis.

- Schliemann's worst offense, by academic standards, is that he may have fabricated Priam's Treasure, or at least combined several disparate finds. His helper, Yannakis, testified that he found some of it in a tomb some distance away. Later it emerged that he had hired a goldsmith to manufacture some artifacts in Mycenaean style, and planted them at the site, a practice known as "salting." Others were collected from other places on the site. Though Sophia was in Athens visiting her family at the time, it is possible she colluded with him on the secret, as he claimed she helped him and she never denied it.

Legacy

Heinrich Schliemann was an archaeologist with great persistence and a desire to discover. Before him, not many believed in the historical accuracy of Homerâs stories. Schliemann, however, had belief and a plan to uncover the famous city of Troy. He pursued this dream and in the end was able to fulfill it, although the methods used to accomplish that are still in question.

Schliemann was not a skilled archaeologist; he was untrained in archaeological techniques and thinking. His digging was done in an unprofessional manner, all in search of hidden treasure. On his way, he destroyed precious artifacts that held no interest for him.

It seems that Schliemann was above all searching for personal glory. However, he influenced numerous later archaeologists, such as Arthur Evans, who were inspired by his findings and initiated their own archaeological searches into the legends of Greek culture. Schliemann's work on the Mycenaean culture can thus be seen as the start of a new global understanding of early Greek history, bringing back to life the people and places of ancient times, whose stories had become considered no more than myths or legends.

Selected bibliography

- Schliemann, H. 1867. La Chine et le Japon au temps present. Paris: Librairie centrale.

- Schliemann, H. [1868] 1973. Ithaka, der Peloponnesus und Troja. Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft. ISBN 3534025245

- Schliemann, H. [1875] 1994. Troy and Its Remains: A Narrative Researches and Discoveries Made on the Site of Ilium and in the Trojan Plain (Troja und seine Ruinen). Dover Publications. ISBN 0486280799

- Schliemann, H. [1878] 1973. Mykenae: Bericht ĂŒber meine Forschungen u. Entdeckungen in Mykenae u. Tiryns. Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft. ISBN 353403290X

- Schliemann, H. 1936. Briefe von Heinrich Schliemann. W. de Gruyter.

- Schliemann, H. 1968. Ilios: The City and Country of the Trojans. Ayer Co. Publishers. ISBN 0405089309

- Schliemann, H. 2000. Bericht ĂŒber die Ausgrabungen in Troja in den Jahren 1871 bis 1873. Artemis and Winkler. ISBN 3760812252

- Schliemann, H. 2003. Auf den Spuren Homers. Stuttgart: Erdmann. ISBN 3522690117

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Boorstin, Daniel. 1985. The Discoverers. Vintage. ISBN 0394726251

- Durant, Will. 1980. The Life of Greece. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 0671418009

- Schlitz, Laura A., and Robert Byrd. 2006. The Hero Schliemann: The Dreamer Who Dug For Troy. Candlewick. ISBN 0763622834

- Silberman, Neil Asher. 1989. Between Past and Present: Archaeology, Ideology, and Nationalism in the Modern Middle East. New York: H. Holt. ISBN 080500906X

- Stone, Irving. 1975. The Greek Treasure: A Biographical Novel of Henry and Sophia Schliemann. Doubleday. ISBN 0385111703

- Wood, Michael. 1998. In Search of the Trojan War. University of California Press. ISBN 0520215990

External links

All links retrieved June 25, 2024.

- Heinrich-Schliemann-Museum Ankershagen â Schliemannâs Museum in Mecklenburg, Germany.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.