Hildegard of Bingen

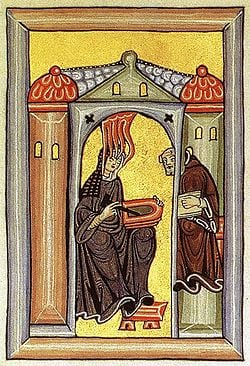

Hildegard of Bingen (1098–1179), also known as Blessed Hildegard and Saint Hildegard, was a German religious teacher, prophetess, and abbess. At a time when women were often not recognized in the public and religious sphere she was also an author, counselor, artist, physician, healer, dramatist, linguist, naturalist, philosopher, poet, political consultant, visionary, and composer of music. She wrote theological, naturalistic, botanical, medicinal, and dietary texts as well as letters, liturgical songs, poems, and the first surviving morality play. She also supervised the production of many brilliant miniature illuminations.

Hildegard was called the "Sibyl of the Rhine" for her prophetic visions and received many notables asking for her guidance. Only two other women come close to rivaling her fame during this period: the abbess, Herrad of Landsberg, born about 1130 and author of the scientific and theological compendium "Hortus Deliciarum" or "Garden of Delights;" and abbess Heloise, 1101-1162 the brilliant scholar of Latin, Greek, and Hebrew, also known for her famous romance with Peter Abelard. Eleanor of Aquitaine was also a contemporary.

Biography

A sickly but gifted child

Hildegard was born into a family of free nobles in the service of the counts of Sponheim, close relatives of the Hohenstaufen emperors. She was the tenth child (the 'tithe' child) of her parents, and was sickly from birth. From the time she was very young, Hildegard experienced visions.

The one surviving tale of Hildegard's childhood involves a prophetic conversation that she held with her nurse, in which she reportedly described an unborn calf as "white… marked with different colored spots on its forehead, feet and back." The nurse, amazed with the detail of the young child's account, told Hildegard's mother, who later rewarded her daughter with the calf, whose appearance Hildegard had accurately predicted. [1].

Hildegard's acetic teacher

Perhaps due to Hildegard's visions, or as a method of political positioning or out of religious duty, Hildegard's parents, Hildebert and Mechthilde, dedicated her at the age of eight to become a nun as a tithe to the Church. Her brothers, Roricus and Hugo became priests and her sister, Clementia, became a nun. Hildegard was placed in the care of Jutta, a wealthy anchoress[2] who was the sister of Count Meinhard of Sponheim. Jutta's cell was located outside the Disibodenberg monastery in the Bavarian region of today's Germany. Jutta was very popular and acquired many followers, such that a small nunnery sprang up around her. She was later declared a saint.

Due to ill health, Hildegard was often left alone. During this time of religious loneliness she received many visions. She says of herself:

Up to my fifteenth year I saw much, and related some of the things seen to others, who would inquire with astonishment, whence such things might come. I also wondered and during my sickness I asked one of my nurses whether she also saw similar things. When she answered no, a great fear befell me. Frequently, in my conversation, I would relate future things, which I saw as if present, but, noting the amazement of my listeners, I became more reticent.

Eventually, Hildegard decided that keeping her visions to herself was the wise choice. She confided them only to Jutta, who in turn told the monk Volmar, Hildegard's tutor and, later, her scribe. Throughout her life, Hildegard continued to have visions.

Called to write

In 1141, already know for her musical poetry and her visionary prose, at 43 years of age, she received a call from God, "Write down that which you see and hear." She was hesitant to record her visions, and soon became physically ill. In her first theological text, 'Scivias, or "Know the Ways," Hildegard describes her inner struggle concerning God's instruction:

I didn’t immediately follow this command. Self-doubt made me hesitate. I analyzed others’ opinions of my decision and sifted through my own bad opinions of myself. Finally, one day I discovered I was so sick I couldn’t get out of bed. Through this illness, God taught me to listen better. Then, when my good friends Richardis and Volmar urged me to write, I did. I started writing this book and received the strength to finish it, somehow, in ten years. These visions weren’t fabricated by my own imagination, nor are they anyone else’s. I saw these when I was in the heavenly places. They are God’s mysteries. These are God’s secrets. I wrote them down because a heavenly voice kept saying to me, 'See and speak! Hear and write!' (Hildegard of Bingen: A Spiritual Reader)

Upon Jutta's death in 1136, Hildegard was unanimously elected as "magistra," or leader of her community. The twelfth century was a time of schisms and religious foment, when controversies attracted followings. Hildegard preached against schismatics, especially the Cathars. She developed a reputation for piety and effective leadership.

Communication with St. Bernard

In 1147, confident about the divine source of her visions, Hildegard was still concerned about whether they should be published, so she wrote to the future Saint Bernard, abbot of the Cistercian monastery of Clairvaux. Her remarkable first letter to the saint has been preserved:

- ...Father, I am greatly disturbed by a vision which has appeared to me through divine revelation, a vision seen not with my fleshly eyes but only in my spirit. Wretched, and indeed more than wretched in my womanly condition, I have from earliest childhood seen great marvels which my tongue has no power to express, but which the Spirit of God has taught me that I may believe. Steadfast gentle father, in your kindness respond to me, your unworthy servant, who has never, from her earliest childhood, lived one hour free from anxiety. In your piety and wisdom look in your spirit, as you have been taught by the Holy Spirit, and from your heart bring comfort to your handmaiden.

Through this vision which touches my heart and soul like a burning flame, teaching me profundities of meaning, I have an inward understanding of the Psalter, the Gospels, and other volumes. Nevertheless, I do not receive this knowledge in German. Indeed, I have no formal training at all, for I know how to read only on the most elementary level, certainly with no deep analysis. But please give me your opinion in this matter, because I am untaught and untrained in exterior material, but am only taught inwardly, in my spirit. Hence my halting, unsure speech …

Bernard, the most influential intellect of his day whose preaching launched crusades and spelled the demise of those who he considered impious, responded favorably. Bernard also advanced her work at the behest of her abbot, Kuno, at the Synod of Trier in 1147 and 1148. When Hildegard's archbishop showed part of Scivias to Pope Eugenius, Bernard encouraged his fellow Cistercian to approve it. Eugenius then encouraged Hildegard to complete her writings. With papal support, Hildegard finished her Scivias in ten years and thus her importance spread throughout the region.

Later Career

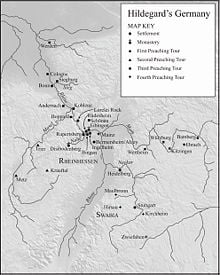

In 1150, amid substantial opposition, Hildegard and 20 members of her community left their former community to establish a new monastery for women, Saint Rupertsberg at Bingen on a mountaintop near the Rhine in 1150, where she became abbess. Archbishop Henry of Mainz consecrated the abbey church in 1152. Fifteen years later, she founded a daughter-house across the Thine at Eibingen.

Many people from all parts of Germany sought her advice and wisdom both in corporal and spiritual ailments. Archbishop Heinrich of Mainz, Archbishop Eberhard of Salzburg and Abbot Ludwig of Saint Eucharius at Trier visited her. Saint Elizabeth of Schönau was a close friend and frequent visitor. Hildegard traveled to both of the houses of Disenberg and Eibingen and to Ingelheim to see Emperor Frederick. From her letters at least four popes and ten archbishops corresponded with her. As well as ten bishops, 21 abbesses and 38 abbots, and a hundred others. Even the renowned Jewish scholar at Mainz would visit her and challenge her knowledge on the Old Testament.

Most noteworthy, was that the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick I (1152-1190), Barbarossa ("Redbeard" in Italian, king of Italy and Burgundy, and the German King) sought out Hildegard as an adviser, although he didn't follow her advice to desist his efforts to undermine Pope Alexander III, until he was soundly defeated by the Pope's forces in 1176.

Many abbots and abbesses asked her for prayers and opinions on various matters. Unique for a women, she traveled widely during her four preaching tours lasting over 13 years which she completed in 1171, at age 73, the only woman to have done so during the Middle Ages (see Scivias, tr. Hart, Bishop, Newman). She visited both men's and women's monasteries and urban Cathedrals to preach to both religious and secular clergy. Her longtime secretary, Volmer, died in 1173, yet she continued to write even after 1175.

Canonization efforts

Hildegard was one of the first souls for which the canonization process was officially applied, but the process took so long that four attempts at canonization (the last was in 1244, under Pope Innocent IV) were not completed, and she remained at the level of her beatification. She has been referred to as a saint by some, with miracles being attributed to her, particularly in contemporary Rhineland, Germany.

As Sister Judith Sutera, O.S.B., of Mount Saint Scholastica explains:

For the first centuries, the ‘naming’ and veneration of saints was an informal process, occurring locally and operating locally…. When they began to codify, between the thirteenth and sixteenth centuries, they did not go back and apply any official process to those persons who were already widely recognized and venerated. They simply ‘grandfathered in’ anyone whose cult had been flourishing for 100 years or more. So many quite famous, ancient, and even non-existent saints who have had feast days and devotions since the apostolic era were never canonized per se.[3]

A vita (an official record of one's life) of Hildegard was written by two monks, Godfrid and Theodoric (Patrologia Latina vol. 197). Hildegard's name was taken up in the Roman martyrology at the end of the sixteenth century. Her feast day is September 17.

Works

Music

Approximately 80 of Hildegard's compositions have survived, which is one of the largest repertoires among medieval composers. Hildegard, in fact, remains the first composer whose biography is known. Among her better known works, 'Ordo Virtutum',' or "Play of the Virtues," is a musical morality play and a rare example of early oratorio for women's voices. It contains only one male part, that of the Devil, who, because of his corrupted nature, cannot sing. The play has served as an inspiration and foundation for what later became known as opera. The oratorio was created, like much of Hildegard's music, for religious ceremonial performance by the nuns of her convent.

Like most religious music of her day, Hildegard's music is monophonic; that is, designed for limited instrumental accompaniment. It is characterized by soaring soprano vocalizations. Today there are numerous recordings available of her work which are still being used and recorded (see References).

Scientific works

In addition to music, Hildegard also wrote medical, botanical and geological treatises, and she even invented an alternative alphabet. The text of her writing and compositions reveals Hildegard's use of this form of modified medieval Latin, encompassing many invented, conflated and abridged words. Due to her inventions of words for her lyrics and a constructed script, many conlangers (people immersed in specialized forms of symbolic communication) look upon her as a medieval precursor.

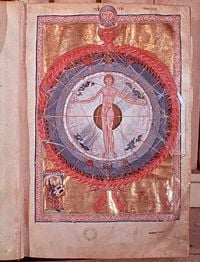

Visionary writings

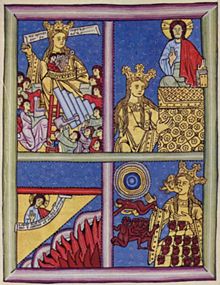

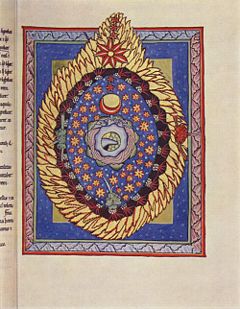

Hildegard collected her visions into three books. The first and most important Scivias ("Know the Way") was completed in 1151. Her visions related in the Scivias were largely about "joy," joy in God and in nature, as she puts it, "in the cosmic egg of creation." Liber vitae meritorum ("Book of Life's Merits"), which dealt with such topics as the forthcoming Apocalype and Purgatory, which was of special interest in the twelfth century, and anti-abortion (although not equating it with murder). De operatione Dei ("Of God's Activities") also known as Liber divinorum operum ("Book of Divine Works"), her most sophisticated theological work, followed in 1163. This volume focused on caritas, the love of God for humans and humans' reciprocal love for Him. In these volumes, written over the course of her life until her death in 1179, she first describes each vision, then interprets it. The narrative of her visions was richly decorated under her direction, presumably by other nuns in the convent, while transcription assistance was provided by the monk Volmar. The liber was celebrated in the Middle Ages and printed for the first time in Paris in 1513. Luckily these illustrations were exactly copied in the 1930s, as the originals were destroyed in Dresden when the British fire-bombed the city toward the end of World War II.

In Scivias, Hildegard was one of the first to interpret the beast in the Book of Revelation as the Antichrist, a figure whose rise to power would parallel Christ's own life, but in a demonic form.

She also wrote The Book of Simple Medicine or Nine Books on the Subtleties of Different Kinds of Creatures, or Natural History, which is a small encyclopedia on the natural sciences. In this volume observation is the key to her understanding. She was unable to oversee the completion of The Book of Composite Medicine (Causes and Cures) and remarkably it has seen recent popularity.

Sexuality

In Hildegard's writings, her conviction, central to her sense of mission is that "virility is a highly desirable quality, which the 'effeminate' male leaders of the Church in her day lacked." So, "weak women," like herself, were called to 'virile' speech and action.[4] She maintained that virginity is the highest level of the spiritual life. Remarkably, she was also the first woman to record a treatise of feminine sexuality, providing scientific accounts of the female orgasm.

When a woman is making love with a man, a sense of heat in her brain, which brings with it sensual delight, communicates the taste of that delight during the act and summons forth the emission of the man's seed. And when the seed has fallen into its place, that vehement heat descending from her brain draws the seed to itself and holds it, and soon the woman's sexual organs contract, and all the parts that are ready to open up during the time of menstruation now close, in the same way as a strong man can hold something enclosed in his fist.

On the other hand, there are many instances, both in her letters and visions, which decry the misuse of carnal pleasures, specifically adultery, homosexuality, and masturbation. In Scivias Book II, Vision Six. 78, she directs those who feel temptation to protect themselves:

… When a person feels himself disturbed by bodily stimulation let him run to the refuge of continence, and seize the shield of chastity, and thus defend himself from uncleanness." (translation by Mother Columba Hart and Jane Bishop).

Significance

Hildegard was a powerful woman, who communicated with Popes such as Eugene III and Anastasius IV; statesmen such as Abbot Suger and the German emperors Frederick I, Barbarossa; and Saint Bernard of Clairvaux. Many people sought out her advice on many topics, both humble people and those of the aristocracy. Her medicinal teachings brought people from far across Europe seeking healing. Her fame grew so that her nunnery grew in size as well. She traveled widely at the invitation of the leadership of the age.

When the convent in Rupertsberg was destroyed in 1632 the relics of the saint were brought to Cologne and then to Eibingen. Hildegard’s Parish and Pilgrimage Church house the relics of Hildegard, including an altar encasing her earthly remains, in Eibingen near Rüdesheim (on the Rhine). On July 2, 1900 the cornerstone was laid for a new convent of Saint Hildegard, and the nuns from Saint Gabriel's at Prague moved into their new home on September 17, 1904.

Modern appraisal

Hildegard's vivid description of the physical sensations which accompanied her visions have been diagnosed by neurologists, including popular author Oliver Sacks, as symptoms of migraine. However, others argue that her migraines could not have produced such vivid and varied religious visions, but instead resulted from authentic divine inspiration.

According to Donald Weinstein and Richard Bell, in their statistical study of saints in Western Christendom between 100 and 1700 C.E. that female saints have claimed illness as a sign of divine favor many times more than male saints have.[4]

In recent years a revival of interest about notable medieval women has caused numerous books to be written about her. Her music is also performed, and numerous recordings have been published.

Notes

- ↑ Sabina Flanagan, Hildegard of Bingen: A Visionary Life (London: Routledge, 1989).

- ↑ An anchorite or anchoress is a monk or nun who shuns the world and lives away from society in an isolated location dedicated to religious life.

- ↑ Carmen Acevedo Butcher, Hildegard of Bingen: A Spiritual Reader (Paraclete Press, 2007, ISBN 1557254907).

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Bonnie Wheeler, Medieval Heroines in History and Legend, part I (The Teaching Company, 2002), lecture nine.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

Selected English Translations of Hildegard

- Baird, Joseph L. (trans.), Radd K. Ehrman. The letters of Hildegard of Bingen. New York: Oxford University Press, 3 vols., 1994-2004. ISBN 0195089375

- Bingen, Hildegard. Secrets of God: Writings of Hildegard of Bingen. Shambhala, 1996. ISBN 978-1570621642

- Butcher, Carmen Acevedo. Incandescence: 365 Readings with Women Mystics. Brewster, MA: Paraclete Press, 2005. ISBN 978-1557254184

- Hart, Mother Columba, and Jane Bishop (trans.). Scivias. Classics of Western Spirituality. New York: Paulist Press, 1990. ISBN 978-0809131303

- Hozeski, Bruce W. (trans.). The Book of the Rewards of Life. (Liber vitae meritorum). New York: Oxford University Press, 1997. ISBN 978-0195113716

- Sweet, Victoria. Rooted in the Earth, Rooted in the Sky: Hildegard of Bingen and Premodern Medicine. New York: Routledge Press, 2006. ISBN 0415976340

- Wheeler, Bonnie. Medieval Heroines in History and Legend, part I. The Teaching Company, 2002. ISBN 156585523X

About Hildegard

- Boyce-Tillman, June. The Creative Spirit: Harmonious Living with Hildegard of Bingen. Harrisburg, PA: Morehouse Publishing, 2000. ISBN 0819218820

- Butcher, Carmen Acevedo. Hildegard of Bingen: A Spiritual Reader. Paraclete Press, 2007. ISBN 978-1557254900

- Ekdahl Davidson, Audrey, ed. (1992). The "Ordo virtutum" of Hildegard of Bingen: critical studies. Kalamazoo, Mich.: Medieval Institute Publications, Western Michigan University, 1992. ISBN 1879288176

- Flanagan, Sabina. Hildegard of Bingen, a Visionary Life. London: Routledge, 1989. ISBN 0760713618

- Fox, Matthew. Illuminations of Hildegard of Bingen. Santa Fe, NM: Bear & Co., 1985. ISBN 1879181975

- Harris, Anne Sutherland and Linda Nochlin, Women Artists: 1550-1950. Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Knopf, New York, 1976. ISBN 0394733266

- Newman, Barbara. God and the Goddesses. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 0812219112

- Newman, Barbara. Sister of wisdom: St. Hildegard's theology of the feminine. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1987. ISBN 0520066154

- Silvas, Anna. (trans). Jutta and Hildegard: the Biographical Sources. (Brepols Medieval Women Series). Penn State University Press, 1999. ISBN 0271019549

- Sweet, Victoria. "Hildegard of Bingen and the Greening of Medieval Medicine." Bulletin of the History of Medicine 73 (1999): 381-403.

Recordings of Hildegard’s Music (Discography)

- 900 Years: Hildegard von Bingen. Sequentia. Box Set (8 discs). RCA 77505, 1998.

- Oak, Ellen. Hildegard of Bingen: The Harmony of Heaven. Bison Publications 1, 1996.

- Page, Christopher, dir. A Feather on the Breath of God: Sequences and Hymns by Abbess Hildegard of Bingen. Gothic Voices, Emma Kirkby (soprano). Hyperion DCA 66039, 1981.

- Sumerly, Jeremy, dir. Hildegard von Bingen: Heavenly Revelations. Oxford Camerata, Naxos 8.550998, 1994.

- Thornton, Barbara, dir. Hildegard von Bingen: Canticles of Ecstasy. Sequentia. Deutsche Harmonia mundi 05472-77320-2, 1994.

This article incorporates text from the Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition, a publication now in the public domain.

External links

All links retrieved July 17, 2024.

- Hildegard of Bingen Abbey website (German)

- Catholic Encyclopedia's article on Hildegard of Bingen

- The Life and Works of Hildegard von Bingen

- Discography

- International Society of Hildegard von Bingen Studies

- Healthy Hildegard

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.