Huangdi Sijing

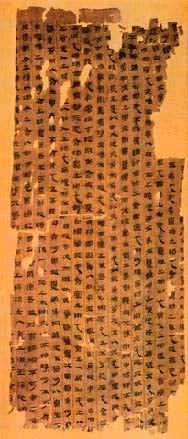

The Huangdi sijing (Traditional Chinese: 黃帝四經; Simplified Chinese: 黄帝四经; pinyin: Huángdì sìjīng; lit. "The Yellow Emperor's Four Classics") are long-lost Chinese manuscripts believed to embody the ancient Chinese "Huang-Lao" philosophy, named after the legendary Huangdi (黃帝 "The Yellow Emperor") and Laozi (老子 "Master Lao"). They were discovered among the Mawangdui Silk Texts found in 1973 in a tomb at the Mawangdui archaeological site, appended to a copy of the Daodejing. In 1975, a Chinese scholar identified these texts as the "Huangdi sijing," a no-longer extant text attributed to the Yellow Emperor. They are also known as the Huang-Lao boshu (Traditional Chinese: 黃老帛書; Simplified Chinese: 黄老帛书; pinyin: Huáng-Lǎo bóshū; lit. "Huang-Lao Silk Texts").

Sima Qian and other early Chinese historians frequently referred to an early Han school of thought known as “Huang-Lao.” After Emperor Wu of Han (r. 141-87 B.C.E.) declared Confucianism the official state philosophy, the followers of Huang-Lao dwindled and their texts largely vanished, leaving scholars puzzled as to the exact nature of its teachings. The Huangdi sijing texts draw elements from many different schools: Lao-zi-style Taoism, Legalism, militarism, Mohism and Confucianism, and the School of Names. The Huangdi sijing reveals complex relationships among the “schools” of Chinese philosophy and demonstrates that the majority of the ancient philosophical texts were not written by a single author, but were collections of works from different sources.

| This article contains Chinese text. Without proper rendering support, you may see question marks, boxes, or other symbols instead of Chinese characters. |

Mawangdui tombs

Mawangdui (Chinese: 馬王堆; pinyin: Mǎwángduī) is an archeological site, comprised of three western-Han-era tombs, found near Changsha in modern Hunan Province (ancient state of Chu). The tombs belonged to Li Cang, the first Marquis of Dai; his wife, and a man in his 30s who died in 168 B.C.E., believed to be their son. In December 1973, archaeologists excavating the tomb of this man ("Tomb Number 3") discovered the “Mawangdui Silk Texts” (Chinese: 馬王堆帛書; pinyin: Mǎwángduī Bóshū), an edifying trove of military, medical, and astronomical manuscripts written on silk that had remained hidden for 2,000 years.

Mawangdui Silk Texts

The Mawangdui Silk Texts include the earliest attested manuscripts of existing texts such as the I Ching; two copies of the Tao Te Ching; one similar copy of Strategies of the Warring States (Zhan Guo Ce) and a similar school of works of Gan De and Shi Shen; a historical text, the Chunqiu shiyu; and various medical texts, including depictions of qigong (tao yin) exercises. Scholars arranged them in to silk books of 28 kinds. Together they amount to about 120,000 words covering military strategy, politics, philosophy, medicine, astronomy, cartography and the six classical arts of ritual, music, archery, horsemanship, writing and arithmetic. Among the texts were copies of the familiar Huangdi Neijing medical classic attributed to the Yellow Emperor, and the previously unknown Book of Silk listing three centuries of comet sightings with two dozen renderings of comets, each accompanied by a caption describing an event that corresponded to the comet's appearance, for example, "the death of the prince," "the coming of the plague," or "the 3 year drought."

The texts on astronomy accurately depicted the planetary orbits for Venus, Jupiter, Mercury, Mars, and Saturn.

The Chinese characters found in the silk texts are often only fragments of the characters used in the traditional versions of those texts that have been handed down through the centuries. Many Chinese characters are formed by combining two simpler Chinese characters, one to indicate a general category of meaning, and one to give an indication of pronunciation. Where the traditional texts have both components, the silk texts frequently give only the phonetic half of the intended character. Several hypotheses have been put forward to explain this: scribes may have hurriedly taken dictation with the intention of completing the characters later; the writers may have felt that their meaning was already clear without the missing components; or they may have been using an abbreviated writing system like the partial characters found in ancient Chinese music (pipa, guqin and guzheng) scores.

In addition to "partial" characters, the silk texts sometimes use characters that differ from those in the traditional received versions, shedding new light on the meaning of certain passages. The received versions of the Tao Te Ching are in substantial agreement with each other, but at some points homonyms with entirely different meanings are used in a passage. A silk text that gives a third character with a different pronunciation that is a synonym for one of the two in the received texts helps to clarify the original meaning.

The four texts

The Mawangdui manuscripts included two silk copies of the Tao Te Ching, eponymously titled Laozi, both of which incorporated other texts and reversed the traditional received chapter arrangement, giving the Dejing chapters before the Daojing. The so-called "B Version" included four previously unknown works, each appended with a title and number of characters (字):

- Jingfa (經法 "The Constancy of Laws"), 5,000 characters

- Shiliu jing (十六經 "The Sixteen Classics"), 4,564 characters

- Cheng (稱 "Aphorisms"), 1,600 characters

- Yuandao (原道 "On Dao the Fundamental"), 464 characters

Owing to holes (lacuna) caused by deterioration in the ancient silk fragments, the original numbers of characters are uncertain.

The two longest texts are subdivided into sections. "The Constancy of Laws" has nine: 1. Dao fa (道法 "The Dao and the Law"), 2. Guo ci (國次 "The Priorities of the State"), 3. Jun zheng (君正 "The Ruler's Government").... "The Sixteen Classics," which some scholars read as Shi da jing (十大經 "The Ten Great Classics"), has fifteen [sic]: 1. Li ming (立命 "Establishing the Mandate"), 2. Guan (觀 "Observation"), 3. Wu zheng (五正 "The Five Norms")….

Early Chinese historians frequently referred to an early Han school of thought known as “Huang-Lao.” In Records of the Grand Historian, Sima Qian says that many early Han thinkers and politicians favored Huang-Lao doctrines during the reigns (202-157 B.C.E.) of Emperor Wen, Emperor Jing, and Empress Dou. Sima cites Han Fei, Shen Buhai, and Shen Dao as representative Huang-Lao philosophers who advocated that sagely rulers should use wuwei to organize their government and society. After Emperor Wu of Han (r. 141-87 B.C.E.) declared Confucianism the official state philosophy, Huang-Lao followers dwindled and their texts largely vanished. Huang Lao was never explained systematically, and for centuries scholars have debated its meaning. “Huang” was understood to be a reference to Huangdi, (the Yellow Emperor) and “Lao” a reference to Laozi. It was thought that Huang Lao was probably an alternative name for Taoism.

The four previously unknown texts appear to be a collection of Huang-Lao texts. One of the four texts represents its ideas as the teachings of the Yellow Emperor or of his advisers. In 1975, the scholar Tang Lan identified these texts as the "Huangdi sijing," a no-longer extant text attributed to the Yellow Emperor, which the Hanshu's Yiwenzhi (藝文志) bibliographical section lists as a Daoist text in four pian (篇 "sections"). Tang analyzed the textual origins and contents, and cited paralleling passages from Chinese classic texts.[1] The "Huangdi sijing" was excluded from the Taoist Canon because it was lost and known only by name. While most scholars agree with Tang's evidence, some disagree and call the texts the Huang-Lao boshu or the Huangdi shu (黃帝書 "The Yellow Emperor's books").

Philosophical significance

Using the four texts of the Huangdi sijing, interpreters have attempted to reconstruct the ideology of Huang-Lao. The texts draw elements from many different schools; Lao-zi-style Daoism is clearly dominant, but Legalism and certain militarist schools contribute significantly. Mohist and Confucian influences are present but generally scattered throughout the texts.[2]

The Huangdi sijing texts provide new insight into the origins of early Chinese philosophy. Traditionally the study of early Chinese thought has been the interpretation of various sets of texts, each attributed to a particular 'Master' and to one of the so-called 'Hundred Schools'.[3]The syncretism of the texts found at Mawangdui indicates that the majority of the ancient philosophical texts were not written by a single author, but were collections of works from different sources.

The Huangdi sijing reveals complex relationships among the “schools” of Chinese philosophy. The first lines in "The Constancy of Laws" echo concepts from several rival philosophies, Daoism, Legalism, Mohism, Confucianism, and School of Names:

The Way generates standards. Standards serve as marking cords to demarcate success and failure and are what clarify the crooked and the straight. Therefore, those who hold fast to the Way generate standards and do not to dare to violate them; having established standards, they do not dare to discard them. [Missing graph] Only after you are able to serve as your own marking cord, will you look at and know all-under-Heaven and not be deluded. (Dao fa, 1.1, tr. De Bary and Lufrano 2001:243)

This passage from The Laws of the Dao (Section 1, iv) incorporates the terms “balance” and “triangulation,” used by the Confucians Mencius and Xunzi:

The impartial is luminous,

the fully luminous has accomplishment;

the fully normed is tranquil,

the fully tranquil is sagely.

Those without partiality are wise,

the fully wise are the standard of the world.

Balance with the scales of discretion,

triangulate with the mark of Heaven,

and when there are affairs in the world

there must be skillful confirmation. [4]

Translations and studies

In the decades since 1973, scholars have published many studies of the Mawangdui manuscripts. In 1974, the Chinese journal Wenwu (文物 "Cultural objects/relics") presented a preliminary transcription into modern characters. The article in which Tang Lan first identified the texts as the "Huangdi sijing in 1975 included photocopies with transcriptions.

The first complete English translation of the Huangdi sijing was produced by Leo S. Chang (appended in Yu 1993:211-326). Subsequent translations include scholarly versions by Yates (1997) and by Chang and Feng (1998), as well as some selected versions. Ryden (1997) provides an informative examination of "The Yellow Emperor's Four Canons".

See also

- Confucianism

- Daoism

- Laozi

- Legalism

- Mohism

- School of Names

- Huangdi

Notes

- ↑ Tang Lan 唐蘭, 1975, "Mawangdui chutu Laozi yiben juanqian guyishu de yanjiu (馬王堆出土《老子》乙本卷前古佚書的研究 "Research on the ancient lost manuscripts preceding the B Version of the Mawangdui Laozi)." Kaogu xuebao (考古學報) 1:7–38.

- ↑ HUANG-LAO IDEOLOGY, University of Indiana. Retrieved January 17, 2009.

- ↑ A Critical Review of the Principal Studies on the Four Manuscripts Preceding the B Version of the Mawangdui Laozi, Paola Carrozza. (2002) B.C. Asian Review 13:49-69. Retrieved January 17, 2009.

- ↑ HUANG-LAO IDEOLOGY, University of Indiana. Retrieved January 17, 2009.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Buck, David D., 1975, Three Han Dynasty Tombs at Ma-Wang-Tui. World Archaeology, 7(1): 30-45.

- Carrozza, Paola. 2002. "A Critical Review of the Principal Studies on the Four Manuscripts Preceding the B Version of the Mawangdui Laozi," B.C. Asian Review 13:49-69.

- Chang, Leo S. and Yu Feng, trs. The Four Political Treatises of the Yellow Emperor: Original Mawangdui Texts with Complete English Translations and an Introduction. University of Hawaii Press. 1998. ISBN 9780824820084

- De Bary, William Theodore and Lufrano, Richard John, eds. Sources of Chinese Tradition: from 1600 through the Twentieth Century. Columbia University Press. 2 vols. 2001. ISBN 9780231112710

- Peerenboom, Randall P. Law and Morality in Ancient China: the Silk Manuscripts of Huang-Lao. State University of New York Press. 1995. ISBN 9780791412374

- Ryden, Edmund, tr. 1997. The Yellow Emperor's Four Canons: a Literary Study and Edition of the Text from Mawangdui. Guangqi chubanshe.

- Shaughnessy, Edward L. I Ching: the Classic of Changes. Classics of ancient China. New York: Ballantine Books. 1996. ISBN 9780345362438

- Tang Lan 唐蘭. 1975. "Mawangdui chutu Laozi yiben juanqian guyishu de yanjiu (馬王堆出土《老子》乙本卷前古佚書的研究 "Research on the ancient lost manuscripts preceding the B Version of the Mawangdui Laozi)." Kaogu xuebao (考古學報) 1:7–38.

- Yates, Robin D.S. Five Lost Classics: Tao, Huang-Lao, and Yin-Yang in Han China. Ballantine Books. 1997. ISBN 9780345365385

- Yu Mingguang 余明光. 1993. Huangdi sijing jinzhu jinyi (黃帝四經今註今譯 "The Huangdi Sijing with modern annotations and translations"). Yuelu shushe.

External links

All links retrieved July 19, 2024.

- Huangdi sijing 黃帝四經 "The Four Classics of the Yellow Emperor" – Ulrich Theobald

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.