Imitation

Imitation is an advanced behavior whereby an action is elicited by an individual's observation and subsequent replication of another's behavior. It is thus the basis of observational learning and socialization. The ability to imitate involves recognizing the actions of another as corresponding to the same physical parts of the observer's body and their movement. Some have suggested that this ability is instinctive, while others regard it as a higher order form of learning. Many of the theories and ideas surrounding imitation can be applied across many disciplines.

While the exact processes by which imitation occurs have been disputed, as has the age at which human beings have the ability to imitate, and which other species have the same ability, it is clear that the ability to imitate is a very powerful learning tool. Through imitation, human beings and other species are able to pass on techniques and skills without need for detailed, verbal instruction. Thus, once one individual has found the solution to a problem, their innovation can be quickly multiplied throughout their community and beyond. On the other hand, behaviors that damage others, such as prejudice, racial discrimination, and aggression are also easily imitated. Thus, whether imitation serves the good of society or ill, depends on the original model of behavior and the ability of those observing to discern and act on their judgment of whether it should be imitated.

Psychology

In psychology, imitation is the learning of behavior through the observation of others. Imitation is synonymous with modeling and has been studied in humans and animals by social scientists in various contexts.

Children learn by imitating adults. Their powerful ability to imitate—that serves them well in so many situations—can actually lead to confusion when they see an adult doing something in a disorganized or inefficient way. They will repeat unnecessary steps, even wrong ones, that they have observed an adult performing, rethinking the purpose of the object or task based on the observed behavior, a phenomenon termed "over-imitation."

What of all of this means is that children’s ability to imitate can actually lead to confusion when they see an adult doing something in a disorganized or inefficient way. Watching an adult doing something wrong can make it much harder for kids to do it right. (Lyons, Young, and Keil, 2007)

Infant research

Some of the fundamental studies of infant imitation are those of Jean Piaget (1951), William McDougall (1908), and Paul Guillaume (1926). Piaget's work is perhaps the most famous and formed the basis of theories of child development.

Piaget's work included a significant amount of experimental data which supported his model of six stages of the development of imitation:

- Stage 1: The preparation for imitation facilitated through reflexes to external stimuli.

- Stage 2: A time of sporadic imitation wherein the child includes new gestures or vocal imitations that are clearly perceived.

- Stage 3: Imitation of sounds and movements that the child has already done or observed.

- Stage 4: Child is able to imitate those around him, even when the movements are not visible.

- Stage 5: Imitation becomes more systematic and the child internalizes these invisible movements.

- Stage 6: Known as deferred imitation, this step in the process refers to imitation that does not occur immediately or in the presence of the demonstrator. The child is now able to internalize a series of models from external stimuli.

Piaget claimed that infants confused the acts of others with their own. Infants will respond to another infant's cry with their own and infants aged four to eight months will mimic the facial expressions of their caregivers. In his book entitled Play, Dreams, and Imitation in Childhood, Piaget claimed that this observed infant behavior could be understood as "pseudo-imitation" because of the lack of intentional effort on the part of the infant. Rather than a display of emotion, the copied expression of the infants to him was more of a reflex. Piaget also viewed imitation as a step between intelligence and sensorimotor response and maintained that the internalization of beliefs, values, or emotions was the child's ability to purposely imitate something from their environment.

Others have disagreed with Piaget's position. The landmark 1977 study by Andrew Meltzoff and Keith Moore showed that 12- to 21-day-old infants could imitate adults who pursed their lips, stuck out their tongue, opened their mouth, and extended their fingers. They argued that this behavior could not be explained in terms of either conditioning or innate releasing mechanisms, but was a true form of imitation. Subsequent research with neonates supported this position. Such imitation implies that human neonates can equate their own unseen behaviors with gestures they see others perform, to the extent that they are capable of imitating them.

Animal research

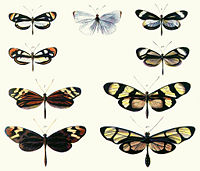

Animal behaviors that are imitated can be understood through social influence. Social influence is any influence that one organism may have on another that produces a behavior in the other organism that is similar. Factors that are typical between and within species are mimicry and contagion. Mimicry involves the imitation of physical appearance between two species. Mertensian or Batesian mimicry occurs when an animal takes on the physical appearance or behavior of another species that has better defenses, thus appearing to predators to be the imitated species. Contagion, which can also be referred to as nemesis, occurs when two or more animals engage in a behavior that is typical of their species. Prime examples of contagion behavior are courtship, herding, flocking, and eating.

When studying imitative behavior in animals, one animal usually observes another animal who performs a novel behavior that has been learned through either classical or operant conditioning. The acquisition of the behavior from the animal who observes the performed novel response is understood to be imitation. The acquisition of the animal's imitation of the novel response can be explained through both motivational factors such as the social facilitation of being around another animal, reinforcement through incentives, and the acquiring of the novel response in order to avoid an aversive stimulus. There are also perceptual factors involved wherein the consequences of the demonstrator draws the attention of the observing animal.

Neuroscience

Research in neuroscience suggests that there are specific mechanisms for imitation in the human brain. It has been proposed that there is a system of "mirror neurons." These mirror neurons fire both when an animal performs an action and when the animal observes the same action performed by another animal, especially with a conspecific animal. This system of mirror neurons have been observed in humans, primates, and certain birds. In humans, mirror neurons are localized in Broca's area and the inferior parietal cortex of the brain. Some scientists consider the discovery of mirror neurons to be one of the most important findings in the field of neuroscience in the last decade.

The Meltzoff and Moore (1977) study showed that neonate humans could imitate adults making facial gestures. A handful of studies on newborn chimps found a similar capacity. It was thought that this ability was limited to the great apes. However, the discovery that rhesus monkeys have “mirror neurons”—neurons that fire both when monkeys watch another animal perform an action and when they perform the same action—suggests they possess the common neural framework for perception and action that is associated with imitation. A study has found that rhesus infants can indeed imitate a subset of human facial gestures—gestures the monkeys use to communicate (Gross 2006).

Anthropology

In anthropology, diffusion theories account for the phenomenon of cultures imitating the ideas or practices of others. Some theories contend that all cultures imitate ideas from one or several original cultures, possibly creating a series of overlapping cultural circles. Evolutionary diffusion theory affirms that cultures are influenced by one another, but also claims that similar ideas can be developed in isolation of one another.

Sociology

In sociology, imitation has been suggested as the basis of socialization and the diffusion of innovations.

Socialization refers to the process of learning one’s culture and how to live within it. For the individual it provides the resources necessary for acting and participating within their society. For the society, socialization is the means of maintaining cultural continuity. Socialization begins when the individual is born, when they enter a social environment where they meet parents and other caregivers. There, the adults impart their rules of social interaction on the children, by example (which the children naturally imitate) and by reward and discipline.

The study of the diffusion of innovations is the study of how, why, and at the rate at which new ideas and technology spread through cultures. French sociologist Gabriel Tarde originally claimed that such development was based on small psychological interactions among individuals, with the fundamental forces being imitation and innovation. Thus, he suggested that once an innovator developed a new idea or product, the imitation of the idea or its use would be the force that allowed it to spread.

Diffusion of innovations theory was formalized by Everett Rogers in his book called Diffusion of Innovations (1962). Rogers stated that individuals who adopt any new innovation or idea could be categorized as innovators, early adopters, early majority, late majority, and laggards. Each adopter's willingness and ability to adopt an innovation would depend on their awareness, interest, evaluation, trial, and adoption. Some of the characteristics of each category of adopters include:

- innovators - venturesome, educated, multiple info sources, greater propensity to take risk

- early adopters - social leaders, popular, educated

- early majority - deliberate, many informal social contacts

- late majority - skeptical, traditional, lower socio-economic status

- laggards - neighbors and friends are main info sources, fear of debt

Rogers also proposed a five stage model for the diffusion of innovation:

- Knowledge - learning about the existence and function of the innovation

- Persuasion - becoming convinced of the value of the innovation

- Decision - committing to the adoption of the innovation

- Implementation - putting it to use

- Confirmation - the ultimate acceptance or rejection of the innovation

Rogers theorized that innovations would spread through society in the logistical function known as the S curve, as the early adopters select the technology first, followed by the majority, until a technology or innovation is commonplace.

The speed of technology adoption is determined by two characteristics p, which is the speed at which adoption takes off, and q, the speed at which later growth occurs. A cheaper technology might have a higher p, for example, taking off more quickly, while a technology that has network effects (such as a fax machine, where the value of the item increases as others get it) may have a higher q.

Critics of the diffusion of innovations theory have suggested that it is an overly simplified representation of a complex reality. A number of other phenomena can influence adoption rates of innovation. Firstly, these customers often adapt technology to their own needs, so the innovation may actually change in nature as number of users increases. Secondly, disruptive technology may radically change the diffusion patterns for established technology by establishing a competing S-curve. Finally, path dependence may lock certain technologies in place. An example of this would be the QWERTY keyboard.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Gross, Liza. Evolution of Neonatal Imitation Evolution of Neonatal Imitation. PLoS Biol 4(9), 2006: e311. Retrieved February 21, 2008.

- Guillaume, Paul. [1926] 1973. Imitation in Children. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0226310466

- Lyons, Derek, Andrew Young, and Frank Keil. 2007. "The Mystery of Overimitation" Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, December 3, 2007.

- McDougall, William. 2001. (1908, revised 1912). An Introduction to Social Psychology. Adamant Media Corporation. ISBN 1421223236

- Meltzoff, Andrew N. and M. Keith Moore. 1977. "Imitation of Facial and Manual Gestures by Human Neonates" Science 7 October 1977: Vol. 198. no. 4312, pp. 75-78.

- Piaget, Jean P. [1951] 1962. Play, Dreams, and Imitation in Childhood. New York, NY: Norton. ISBN 978-0393001716

- Rogers, Everett M. [1962] 2003. Diffusion of Innovation. New York, NY: Free Press. ISBN 0743222091

- Weaver, Jacqueline. 2007. Humans appear hardwired to learn by 'over imitation' Retrieved February 21, 2008.

- Wyrwicka, Wanda. 1995. Imitation in Human and Animal Behavior. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers. ISBN 978-1560002468

- Zentall,Tom and Chana Akins. Imitation in Animals: Evidence, Functions, and Mechanisms Retrieved February 21, 2008.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.