|

| Intellectual property law |

| Rights |

| Authors' rights · Intellectual property · Copyright Database right · Indigenous intellectual property Industrial design rights · Geographical indication Patent · Related rights · Trademark Trade secret · Utility model |

| Related topics |

| Fair use · Public domain Trade name |

Intellectual property (IP) refers to the intangible creations of the human intellect. There are many types of intellectual property, and some countries recognize more than others. The most well-known types are copyrights, patents, trademarks, and trade secrets.

The main purpose of intellectual property law is to encourage the creation of a wide variety of intellectual goods, which benefits society as a whole, or the "public good," while still assigning rights to their creators. To achieve this, the law gives people and businesses property rights to the information and intellectual goods they create, usually for a limited period of time. However, the intangible nature of intellectual property presents difficulties when compared with traditional property like land or goods. Balancing rights so that they are strong enough to encourage the creation of intellectual goods, but not so strong that they prevent the goods' wide use is the primary focus of modern intellectual property law.

Definition

According to the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO):

Intellectual property (IP) refers to creations of the mind, such as inventions; literary and artistic works; designs; and symbols, names and images used in commerce.[1]

The World Trade Organization (WTO) defines intellectual property as follows:

Intellectual property rights are the rights given to persons over the creations of their minds. They usually give the creator an exclusive right over the use of his/her creation for a certain period of time.[2]

History

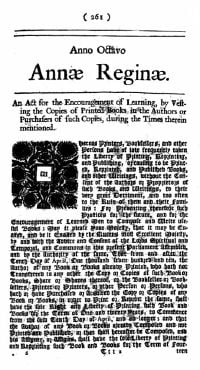

The Statute of Monopolies (1624) and the British Statute of Anne (1710) are seen as the origins of patent law and copyright respectively, firmly establishing the concept of intellectual property.[3]

"Literary property" was the term predominantly used in the British legal debates of the 1760s and 1770s over the extent to which authors and publishers of works also had rights deriving from the common law of property (Millar v Taylor (1769), Hinton v Donaldson (1773), Donaldson v Becket (1774)). The first known use of the term "intellectual property" dates to this time, when a piece published in the Monthly Review in 1769 used the phrase: "What a niggard this Doctor is of his own, and how profuse he is of other people's intellectual property." [4] The first clear example of modern usage goes back as early as 1808, when it was used as a heading title in a collection of essays: "New-England Association in favour of Inventors and Discoverers, and particularly for the Protection of intellectual Property."[5]

The term can be found used in an October 1845 Massachusetts Circuit Court ruling in the patent case Davoll et al. v. Brown., in which Justice Charles L. Woodbury wrote that "only in this way can we protect intellectual property, the labors of the mind, productions and interests are as much a man's own ... as the wheat he cultivates, or the flocks he rears." The statement that "discoveries are ... property" goes back earlier. Section 1 of the French law of 1791 stated, "All new discoveries are the property of the author; to assure the inventor the property and temporary enjoyment of his discovery, there shall be delivered to him a patent for five, ten or fifteen years."[6] In Europe, French author Alfred Nion mentioned propriété intellectuelle in his Droits civils des auteurs, artistes et inventeurs, published in 1846.[7]

When the administrative secretariats established by the Paris Convention (1883) and the Berne Convention (1886) merged in 1893, they located in Berne, and also adopted the term intellectual property in their new combined title, the United International Bureaux for the Protection of Intellectual Property.

The organization subsequently relocated to Geneva in 1960 and was succeeded in 1967 with the establishment of the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) by treaty as an agency of the United Nations. According to legal scholar Mark Lemley, it was only at this point that the term really began to be used in the United States (which had not been a party to the Berne Convention), and it did not enter popular usage there until passage of the Bayh-Dole Act in 1980.[8]

The history of patents does not begin with inventions, but rather with royal grants by Queen Elizabeth I (1558–1603) for monopoly privileges. Approximately 200 years after the end of Elizabeth's reign, however, a patent represents a legal right obtained by an inventor providing for exclusive control over the production and sale of his mechanical or scientific invention. demonstrating the evolution of patents from royal prerogative to common-law doctrine.[9]

Until recently, the purpose of intellectual property law was to give as little protection as possible in order to encourage innovation. Historically, therefore, they were granted only when they were necessary to encourage invention, limited in time and scope.[8] This is mainly as a result of knowledge being traditionally viewed as a public good, in order to allow its extensive dissemination and improvement thereof.[10]

According to Jean-Frédéric Morin, "the global intellectual property regime is currently in the midst of a paradigm shift."[11] Indeed, up until the early 2000s the global IP regime used to be dominated by high standards of protection characteristic of IP laws from Europe or the United States, with a vision that uniform application of these standards over every country and to several fields with little consideration over social, cultural or environmental values or of the national level of economic development. Morin argues that "the emerging discourse of the global IP regime advocates for greater policy flexibility and greater access to knowledge, especially for developing countries." Indeed, with the Development Agenda adopted by WIPO in 2007, a set of 45 recommendations to adjust WIPO's activities to the specific needs of developing countries and aim to reduce distortions especially on issues such as patients’ access to medicines, Internet users’ access to information, farmers’ access to seeds, programmers’ access to source codes or students’ access to scientific articles. However, this paradigm shift has not yet manifested itself in concrete legal reforms at the international level.[11]

Rights

There are many types of intellectual property. The WTO notes two main areas: (1) Copyright and rights related to copyright; and (2) Industrial property.[2]

The European Union (EU) characterizes intellectual property into two types as follows:

Intellectual property includes all exclusive rights to intellectual creations. It encompasses two types of rights: industrial property, which includes inventions (patents), trademarks, industrial designs and models and designations of origin, and copyright, which includes artistic and literary property.[12]

Patents

A patent is a form of right granted by the government to an inventor or their successor-in-title, giving the owner the right to exclude others from making, using, selling, offering to sell, and importing an invention for a limited period of time, in exchange for the public disclosure of the invention:

A patent is an exclusive right granted for an invention, which is a product or a process that provides, in general, a new way of doing something, or offers a new technical solution to a problem. To get a patent, technical information about the invention must be disclosed to the public in a patent application.[13]

An invention is a solution to a specific technological problem, which may be a product or a process, and generally has to fulfill these requirements: it has to be new, not obvious, there needs to be an industrial applicability, its subject matter must be accepted as “patentable” under law, and the invention must be disclosed in an application such that it can be replicated by a person with an ordinary level of skill in the relevant technical field.[14]

Copyright

A copyright gives the creator of an original work exclusive rights to it, usually for a limited time. Copyright may apply to a wide range of creative, intellectual, or artistic forms, or "works."[15] Copyright does not cover ideas and information themselves, only the form or manner in which they are expressed.[16]

Industrial design rights

An industrial design right (sometimes called "design right" or "design patent") protects the visual design of objects that are not purely utilitarian: An industrial design constitutes the ornamental aspect of an article.[17]

An industrial design consists of the creation of a shape, configuration, or composition of pattern or color, or combination of pattern and color in three-dimensional form containing aesthetic value. An industrial design can be a two- or three-dimensional pattern used to produce a product, industrial commodity, or handicraft. Generally speaking, it is what makes a product look appealing, and as such, it increases the commercial value of goods.

Plant varieties

Plant breeders' rights or plant variety rights (PVR) are a form of intellectual property used to protect unique plant varieties. Plant varieties awarded PVR status are freely available to others for use in future breeding programs, and plant breeders collect royalties on the production and sale of seed of their protected varieties. In this way, the PVR system both delivers protection and stimulates further innovation in plant breeding.

To qualify for Plant Variety Rights, a new variety must undergo official tests to determine whether it is distinct (clearly distinguishable from any other existing variety by one or more characteristics), uniform (individual plants must be sufficiently uniform in a range of key characteristics), and stable (the plant variety reproduces true to type from one generation to the next).[18]

Trademarks

A trademark is a recognizable word, phrase, symbol, and/or design that distinguishes products or services of a particular trader from similar products or services of other traders.[19]

A trade mark is a sign which can distinguish your goods and services from those of your competitors (you may refer to your trade mark as your “brand”). ... In other words they can be recognised as signs that differentiates your goods or service as different from someone else’s.[20]

Trade dress

Trade dress is a legal term of art that generally refers to characteristics of the visual and aesthetic appearance of a product or its packaging (or even the design of a building) that signify the source of the product to consumers.[21]

Trade secrets

A trade secret is a formula, practice, process, design, instrument, pattern, or compilation of information which is not generally known or reasonably ascertainable, by which a business can obtain an economic advantage over competitors and customers. Two of the most famous trade secrets in the United States, for example, are the recipe for Coca Cola and Colonel Harland Sanders' handwritten Original Recipe(R) for Kentucky Fried Chicken.

There is no formal government protection granted; each business must take measures to guard its own trade secrets. A company can protect its confidential information through Non-disclosure agreements (NDA) and non-compete clauses for employees, and confidentiality agreements for vendors or third parties in business negotiations. The protection of a trade secret is perpetual and does not expire after a specific length of time, as a patent does. The lack of formal protection, however, means that a third party is not prevented from independently duplicating and using the secret information once it is discovered.

Motivation and justification

The intangible nature of intellectual property presents difficulties when compared with traditional property like land or goods. Unlike traditional property, intellectual property is indivisible – an unlimited number of people can "consume" an intellectual good without it being depleted. Additionally, investments in intellectual goods suffer from problems of appropriation – while a landowner can surround their land with a robust fence and hire armed guards to protect it, a producer of information or an intellectual good can usually do very little to stop their first buyer from replicating it and selling it at a lower price. Balancing rights so that they are strong enough to encourage the creation of information and intellectual goods but not so strong that they prevent their wide use is the primary focus of modern intellectual property law.[22]

The main purpose of intellectual property law is to encourage the creation of a wide variety of intellectual goods for consumers.[22] To achieve this, the law gives people and businesses property rights to the information and intellectual goods they create, usually for a limited period of time. Because they can then profit from them, this gives economic incentive for their creation.[22] By exchanging limited exclusive rights for disclosure of inventions and creative works, society and the patentee/copyright owner mutually benefit, and an incentive is created for inventors and authors to create and disclose their work.

Other developments in intellectual property law, such as the America Invents Act, stress international harmonization. There has also been much debate over the desirability of using intellectual property rights to protect cultural heritage, including intangible ones, as well as over risks of commodification derived from this possibility.[23]

Financial incentive

Exclusive rights allow owners of intellectual property to benefit from the property they have created, providing a financial incentive for the creation of an investment in intellectual property. The United States Article I Section 8 Clause 8 of the Constitution, commonly called the Patent and Copyright Clause, reads:

The Congress shall have power "To promote the progress of science and useful arts, by securing for limited times to authors and inventors the exclusive right to their respective writings and discoveries."[24]

Economic growth

These economic incentives are expected to stimulate innovation and contribute to technological progress, leading to economic growth.[25]

The WIPO treaty and several related international agreements underline that the protection of intellectual property rights is essential to maintaining economic growth. The Anti-Counterfeiting Trade Agreement (ACTA) states that "effective enforcement of intellectual property rights is critical to sustaining economic growth across all industries and globally."[26]

A joint research project of the WIPO and the United Nations University measuring the impact of IP systems on six Asian countries found "a positive correlation between the strengthening of the IP system and subsequent economic growth."[27]

Morality

In the nineteenth century, Lysander Spooner argued:

that a man has a natural and absolute right—and if a natural and absolute, then necessarily a perpetual, right—of property, in the ideas, of which he is the discoverer or creator; that his right of property, in ideas, is intrinsically the same as, and stands on identically the same grounds with, his right of property in material things; that no distinction, of principle, exists between the two cases.[28]

If one believes that intellectual property is no different from material property, then it follows that the same moral rights that govern material property apply to intellectual property. For example, Ayn Rand argued that the human mind itself is the source of wealth and survival and that all property at its base is intellectual property. To violate intellectual property is therefore no different morally than violating other property rights which compromises the very processes of survival and therefore constitutes an immoral act.[29]

According to Article 27 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, "everyone has the right to the protection of the moral and material interests resulting from any scientific, literary or artistic production of which he is the author."[30] Although the relationship between intellectual property and human rights is a complex one, there are moral arguments for intellectual property.

The arguments that justify intellectual property rights fall into three major categories: Lockeans argue that intellectual property is justified based on deservedness and hard work; Utilitarians believe that intellectual property stimulates social progress and pushes people to further innovation; and personality theorists regard intellectual property as an extension of an individual.[31]

- Natural Rights/Justice Argument: This argument is based on John Locke's idea that a person has a natural right over the labor and products which are produced by their body. Appropriating these products is viewed as unjust. Although Locke never explicitly stated that this natural right applied to products of the mind,[32] it is possible to apply his argument to intellectual property rights, in which it would be unjust for people to misuse another's ideas.[33]

- Utilitarian-Pragmatic Argument: According to this rationale, a society that protects private property is more effective and prosperous than societies that do not. Utilitarians argue that without intellectual property there would be a lack of incentive to produce new ideas. Innovation and invention in nineteenth century America has been attributed to the development of the patent system.[33] By providing innovators with "durable and tangible return on their investment of time, labor, and other resources," intellectual property rights promote public welfare by encouraging the "creation, production, and distribution of intellectual works."[34]

- "Personality" Argument: This argument is based on a quote from Hegel, "Every man has the right to turn his will upon a thing or make the thing an object of his will, that is to say, to set aside the mere thing and recreate it as his own," which leads to the understanding that ideas are an "extension of oneself and of one's personality."[33] Personality theorists argue that by being a creator of something one is inherently at risk and vulnerable for having their ideas and designs stolen and/or altered.

Infringement, misappropriation, and enforcement

Violation of intellectual property rights, called "infringement" with respect to patents, copyright, and trademarks, and "misappropriation" with respect to trade secrets, may be a breach of civil law or criminal law, depending on the type of intellectual property involved, jurisdiction, and the nature of the action.

Patent infringement

Patent infringement typically is caused by using or selling a patented invention without permission from the patent holder. The scope of the patented invention or the extent of protection is defined in the claims of the granted patent. The definition of patent infringement may vary by jurisdiction, but it typically includes using or selling the patented invention.

There is safe harbor in many jurisdictions to use a patented invention for research. However, safe harbor does not exist in the US unless the research is done for purely philosophical purposes, or in order to gather data in order to prepare an application for regulatory approval of a drug.[35]

Patents are territorial, and infringement is only possible in a country where a patent is in force. For example, if a patent is granted in the United States, then anyone in the United States is prohibited from making, using, selling, or importing the patented item, while people in other countries may be free to exploit the patented invention in their country.

In general, patent infringement cases are handled under civil law in the United States, but infringement in criminal law may be included in some jurisdictions.

Copyright infringement

Copyright infringement (colloquially referred to as "piracy") is the unlawful use of works protected by copyright law without permission for a usage where such permission is required, thereby infringing certain exclusive rights granted to the copyright holder, such as the right to reproduce, distribute, display, or perform the protected work, or to make derivative works.[36] The copyright holder is typically the work's creator, or a publisher or other business to whom copyright has been assigned.

Enforcement of copyright is generally the responsibility of the copyright holder.[37]

There are limitations and exceptions to copyright, allowing limited use of copyrighted works, which does not constitute infringement. Examples of such doctrines are the fair use and fair dealing doctrine.

Trademark infringement

Trademark infringement is a violation of the exclusive rights attached to a trademark without the authorization of the trademark owner or any licensees (provided that such authorization was within the scope of the license). Infringement may occur when one party, the "infringer," uses a trademark which is identical or confusingly similar to a trademark owned by another party, in relation to products or services which are identical or similar to the products or services which the registration covers. An owner of a trademark may commence civil legal proceedings against a party which infringes its registered trademark.

In the United States, the Trademark Counterfeiting Act of 1984 criminalized the intentional trade in counterfeit goods and services.

Trade secret misappropriation

Trade secret misappropriation is different from violations of other intellectual property laws, since by definition trade secrets are secret, while patents and registered copyrights and trademarks are publicly available. Acts of industrial espionage are generally illegal in their own right under the relevant governing laws, and penalties can be harsh.

In the United States, trade secrets are protected under state law, and states have nearly universally adopted the Uniform Trade Secrets Act. The United States also has federal law in the form of the Economic Espionage Act of 1996 (), which makes the theft or misappropriation of a trade secret a federal crime. This law contains two provisions criminalizing two sorts of activity. The first, , criminalizes the theft of trade secrets to benefit foreign powers. The second, , criminalizes their theft for commercial or economic purposes.

Criticisms

A major issue with regard to intellectual property is the question of whether it can be treated as "property" at all. The words of Thomas Jefferson written in a letter to Isaac McPherson on August 13, 1813, are pertinent:

If nature has made any one thing less susceptible than all others of exclusive property, it is the action of the thinking power called an idea, which an individual may exclusively possess as long as he keeps it to himself; but the moment it is divulged, it forces itself into the possession of every one, and the receiver cannot dispossess himself of it. Its peculiar character, too, is that no one possesses the less, because every other possesses the whole of it. He who receives an idea from me, receives instruction himself without lessening mine; as he who lights his taper at mine, receives light without darkening me. That ideas should freely spread from one to another over the globe, for the moral and mutual instruction of man, and improvement of his condition, seems to have been peculiarly and benevolently designed by nature, when she made them, like fire, expansible over all space, without lessening their density in any point, and like the air in which we breathe, move, and have our physical being, incapable of confinement or exclusive appropriation. Inventions then cannot, in nature, be a subject of property.[38]

Such distinctions between physical (tangible) and intellectual property are undeniable, and recognized by the framers of intellectual property law, whose purpose was to promote advances in science and the arts, while protecting the inventors and creators of their work from piracy. Thus, intellectual property protection includes term limits:

After authors have been given a decent interval to exploit their property, the monopoly to the work is ended, and the work may be reabsorbed into the culture at large, be remixed into new works, for the public benefit for the rest of time: hence the name "Public Domain" which refers to the domain of this public good.[39]

Term limits notwithstanding, critics continue to reject the implied close connection with tangible property that intellectual property law guarantees. Their primary complaint lies with the term itself.

The term "intellectual property"

Criticism of the term "intellectual property" ranges from discussing its vagueness and abstract overreach to direct contention concerning the semantic validity of using words like "property" and "rights" which lead to "the idea that it's just like regular property."[40]

Law professor, writer and political activist Lawrence Lessig, along with many other copyleft and free software activists, have criticized this implied analogy with physical property (like land or an automobile). They argue such an analogy fails because physical property is generally rivalrous while intellectual works are non-rivalrous (that is, if one makes a copy of a work, the enjoyment of the copy does not prevent enjoyment of the original).[39]

Other arguments along these lines claim that unlike the situation with tangible property, there is no natural scarcity of a particular idea or information: once it exists, it can be re-used and duplicated indefinitely without such re-use diminishing the original:

When it comes to copying, this analogy disregards the crucial difference between material objects and information: information can be copied and shared almost effortlessly, while material objects can't be.[41]

The term "intellectual property," by including the word "property" implies scarcity, which may not be applicable to ideas.[42]

Alternative terms

Alternative terms, such as "Intellectual Monopoly," "Intellectual Privilege," "Imaginary Property," and others, have been suggested to replace "Intellectual Property."[40] "Imaginary Property" does not solve the problem of the implied connection to real property given that it continues to use the term; and the nature of intellectual property defined as :creations of the mind, such as inventions; literary and artistic works; designs; and symbols, names and images used in commerce" is hardly imaginary.

"Intellectual Privilege" loses the term "property" but adds the term "privilege," for reasons which are not immediately apparent, especially when applied to laws of protection.

Economists Michele Boldrin and David K. Levine support the use of the term "intellectual monopoly" as a more appropriate and clear definition of the concept. They argue that rights to intellectual creations are very dissimilar from property rights, creating market monopolies rather than protecting the rights of the owner.[43]

For many, however, given the problems with the term, and the great differences among the areas to which it is applied, the conclusion is that it is better to use the specific terms, "copyright," or "patent," or "trademark," and so forth, rather than employing a general and misleading term.[41]

Overbroad intellectual property laws

In 2001 the United Nations Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights concluded that intellectual property (IP) tends to be governed by economic goals when it should be viewed primarily as a social product. In order to serve human well-being, intellectual property systems must respect and conform to human rights laws. According to the Committee, when systems fail to do so they risk infringing upon the human right to food and health, and to cultural participation and scientific benefits.[44]

Such ethical problems are most pertinent when socially valuable goods like life-saving medicines are given IP protection. While the application of IP rights can allow companies to charge higher than the marginal cost of production in order to recoup the costs of research and development, the price may exclude from the market anyone who cannot afford the cost of the product, in this case a life-saving drug: "An IPR driven regime is therefore not a regime that is conductive to the investment of R&D of products that are socially valuable to predominately poor populations."[45]

In 2004 the General Assembly of the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) adopted The Geneva Declaration on the Future of the World Intellectual Property Organization which calls on WIPO to "focus more on the needs of developing countries, and to view IP as one of many tools for development—not as an end in itself."[46]

Critics have also noted that the objective of intellectual property legislators and those who support its implementation appears to be "absolute protection." The typical argument for broad protection is as follows:

If some intellectual property is desirable because it encourages innovation, they reason, more is better. The thinking is that creators will not have sufficient incentive to invent unless they are legally entitled to capture the full social value of their inventions.[8]

Boldrin and Levine have disputed this justification. Citing problems such as inflated prices of pharmaceuticals to satisfy the patent holders leading to patients being unable to pay for needed medication, as well young people's "pirating" of high priced musical recordings simply to enjoy a wide variety of music, they suggest that rather than encouraging innovation, the protection given by intellectual property laws hinders rather than helps the competitive free market by creating "intellectual monopolies.”[43]

Historical analysis supports the contention that intellectual property laws may harm innovation:

Overall, the weight of the existing historical evidence suggests that patent policies, which grant strong intellectual property rights to early generations of inventors, may discourage innovation. On the contrary, policies that encourage the diffusion of ideas and modify patent laws to facilitate entry and encourage competition may be an effective mechanism to encourage innovation.[47]

Duration and scope

The duration and scope of intellectual property rights have also been the subject of discussion and criticism.

Arguments have been advanced that copyright should be renewable, or even have no term limits at all.[48] Changes in copyright law in the United States, such as the 1976 Copyright Act and the Sonny Bono Copyright Term Extension Act of 2008, eliminated the registration and notice requirements, and extended the duration of copyright. These changes increased the likelihood that of orphan works (copyrighted works for which the copyright owner cannot be contacted), a problem that has been noticed and addressed by governmental bodies around the world.[49]

International efforts to harmonize the definition of "trademark" have led to expansion in scope. For example, the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights ratified in 1994, formalized regulations for IP rights that had been handled by common law, or not at all, in member states. Pursuant to TRIPs, any sign which is "capable of distinguishing" the products or services of one business from the products or services of another business is capable of constituting a trademark.[50]

In terms of scope, as scientific knowledge has expanded and allowed new industries to arise in fields such as biotechnology and nanotechnology, originators of technology have sought IP protection for the new technologies. Patents have been granted for living organisms, usually plants.[51]

The electronic age has seen an increase in the attempt to use software-based digital rights management tools to restrict the copying and use of digitally based works. Laws such as the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA) have been enacted that use criminal law to prevent any circumvention of software used to enforce digital rights management systems. This can hinder legal uses, affecting public domain works, limitations and exceptions to copyright, or uses allowed by the copyright holder. Some copyleft licenses, like GNU GPL 3, are designed to counter that.[52]

Intellectual property law has also been criticized for not recognizing new forms of art such as remixes, anime music videos and others, which are derivative works by combining or editing existing materials to produce a new creative work or product. The creation of such works technically constitutes violations of copyright law, or are otherwise subject to unnecessary burdens and limitations which prevent the creators from fully expressing themselves.[53]

Notes

- ↑ What is Intellectual Property? World Intellectual Property Organization. Retrieved January 19, 2021.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 What are intellectual property rights? World Trade Organization. Retrieved January 19, 2021.

- ↑ Brad Sherman and Lionel Bently, The Making of Modern Intellectual Property Law (Cambridge University Press, 1999, ISBN 978-0521563635).

- ↑ Ralph Griffiths, The Monthly Review, Or, Literary Journal; Volume 61 (Wentworth Press, 2019, ISBN 978-1012313951).

- ↑ Samuel Latham Mitchell and Edward Miller, Medical Repository Of Original Essays And Intelligence (1808), 303. Retrieved January 19, 2021.

- ↑ A Brief History of the Patent Law of the United States Ladas & Parry, May 7, 2014. Retrieved January 20, 2021.

- ↑ Alfred Nion, Droits civils des auteurs, artistes et inventeurs (Civil rights of authors, artists and inventors) (HardPress Publishing, 2019, ISBN 978-0371209462).

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Mark Lemley, Property, Intellectual Property, and Free Riding Texas Law Review 83 (2005). Retrieved January 20, 2021.

- ↑ Adam Mossoff, Rethinking the Development of Patents: An Intellectual History, 1550–1800 Hastings Law Journal 52 (2001). Retrieved January 20, 2021.

- ↑ The Liquidity of Innovation The Economist, October 22, 2005. Retrieved January 20, 2021.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Jean-Frédéric Morin, Paradigm shift in the global IP regime: The agency of academics Review of International Political Economy 21(2) (2014): 275–309. Retrieved January 20, 2021.

- ↑ Intellectual, industrial and commercial property European Parliament. Retrieved January 19, 2021.

- ↑ What is a patent? WIPO. Retrieved January 21, 2021.

- ↑ Applying for patent protection WIPO. Retrieved January 21, 2021.

- ↑ Peter K. Yu, Intellectual Property and Information Wealth (Praeger, 2006, ISBN 978-0275988821).

- ↑ Simon Stokes, Art and Copyright (Hart Publishing, 2001, ISBN 978-1841132259).

- ↑ https://www.wipo.int/designs/en/ What is an industrial design?] WIPO. Retrieved January 21, 2021.

- ↑ Plant Variety Rights Retrieved January 21, 2021.

- ↑ Trademark, Patent, or Copyright? US Trademark and Patent Office. Retrieved January 21, 2021.

- ↑ Unacceptable trade marks Intellectual Property Office, May 16, 2014. Retrieved January 21, 2021.

- ↑ Peter S. Menell, Mark A. Lemley, Robert P. Merges, and Shyamkrishna Balganesh, Intellectual Property in the New Technological Age (Clause 8 Publishing, 2020, ISBN 978-1945555152).

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 Paul Goldstein and R. Anthony Reese, Copyright, Patent, Trademark and Related State Doctrines: Cases and Materials on the Law of Intellectual Property (Foundation Press, 2010, ISBN 978-1599417899).

- ↑ Paolo Davide Farah and Ricardo Tremolada, Desirability of Commodification of Intangible Cultural Heritage: The Unsatisfying Role of Intellectual Property Rights Transnational Dispute Management 11(2) (March 2014). Retrieved January 21, 2021.

- ↑ U.S. Constitution Article I Section 8 Clause 8 Stanford University Libraries. Retrieved January 22, 2021.

- ↑ Rod Falvey, Neil Foster, and David Greenaway, Intellectual Property Rights and Economic Growth Review of Development Economics 10(4) (November 2006): 700-719. Retrieved January 21, 2021.

- ↑ Anti-Counterfeiting Trade Agreement Global Affairs Canada. Retrieved January 22, 2021.

- ↑ Measuring the Economic Impact of Intellectual Property Systems WIPO, July, 2007. Retrieved January 22, 2021.

- ↑ Lysander Spooner, The Law of Intellectual Property Anodos Books, 2018, ISBN 978-1725719620).

- ↑ Ayn Rand, Capitalism: The Unknown Ideal (Signet, 1986, ISBN 978-0451147950).

- ↑ The Universal Declaration of Human Rights United Nations.

- ↑ Intellectual Property Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, October 10, 2018. Retrieved January 22, 2021.

- ↑ Ronald V. Bettig, "Critical Perspectives on the History and Philosophy of Copyright" in Copyrighting Culture: The Political Economy of Intellectual Property by Ronald V. Bettig (Routledge, 1996. ISBN 978-0813333045), 19–20.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 33.2 Richard T. De George, "Intellectual Property Rights," in The Oxford Handbook of Business Ethics, by George G. Brenkert and Tom L. Beauchamp (eds.) (Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, 2012, ISBN 978-0199916221), 415–418.

- ↑ Richard A. Spinello and Maria Bottis, A Defense of Intellectual Property Rights (Edward Elgar Pub, 2009, ISBN 978-1847203953).

- ↑ Alicia A. Russo and Jason Johnson, Research Use Exemptions to Patent Infringement for Drug Discovery and Development in the United States Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Medicine 5(2) (February 2015). Retrieved January 22, 2021.

- ↑ Darrell Panethiere, The Persistence of Piracy: The Consequences for Creativity, for Culture, and for Sustainable Development e-Copyright Bulletin (April-June, 2005). Retrieved January 22, 2021.

- ↑ Xuan Li and Carlos M. Correa (eds.), Intellectual Property Enforcement: International Perspectives (Edward Elgar Pub, 2009, ISBN 978-1848446526).

- ↑ Thomas Jefferson to Isaac McPherson August 13, 1813. Retrieved January 23, 20201

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 Lawrence Lessig, Against perpetual copyright The Lessig Wiki. Retrieved January 23, 2021.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 Mike Masnick, If Intellectual Property Is Neither Intellectual, Nor Property, What Is It? Tech Dirt, March 6, 2008. Retrieved January 23, 2021.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 Richard Stallman, Words to Avoid (or Use with Care) Because They Are Loaded or Confusing GNU Operating System. Retrieved January 23, 2021.

- ↑ Stephan Kinsella, Against Intellectual Property Journal of Libertarian Studies 15(2) (Spring 2001):1–53. Retrieved January 23, 2021.

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 Michele Boldrin and David K. Levine, Against Intellectual Monopoly (Cambridge University Press, 2010, ISBN 978-0521127264).

- ↑ Human rights and intellectual property UN Committee on Economic Social and Cultural Rights, Geneva, November 12–30, 2001. retrieved January 23, 2021.

- ↑ Jorn Sonderholm, Ethical Issues Surrounding Intellectual Property Rights Philosophy Compass 5(12) (2010): 1107–1115. Retrieved January 23, 2021.

- ↑ Geneva Declaration on the Future of the World Intellectual Property Organization October 4, 2004. Retrieved January 23, 2021.

- ↑ Petra Moser, Patents and Innovation: Evidence from Economic History Journal of Economic Perspectives 27(1) (2013): 23–44. Retrieved January 23, 2021.

- ↑ Mark Helprin, A Great Idea Lives Forever. Shouldn't Its Copyright? The New York Times, May 20, 2007. Retrieved January 23, 2021.

- ↑ Library of Congress Copyright Office Docket No. 2012–12 Orphan Works and Mass Digitization Federal Register 77(204) (October 22, 2012): 64555–64561. Retrieved January 23, 2021. See page 64555 first column for international efforts and third column for description of the problem.

- ↑ Katherine Beckman and Christa Pletcher, Expanding Global Trademark Regulation Wake Forest Intellectual Property Law Journal 10(2) (2009): 215–239. Retrieved January 23, 2021.

- ↑ Jake Mace, Can a living organism be patented? The quick answer is “sometimes.” IP Wire, July 31, 2017. Retrieved January 23, 2021.

- ↑ Brett Smith, A Quick Guide to GPLv3 GNU Operating System. Retrieved January 23, 2021.

- ↑ Dariusz Jemielniak and Aleksandra Przegalinska, Collaborative Society (The MIT Press, 2020, ISBN 978-0262537919).

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Bettig, Ronald V. Copyrighting Culture: The Political Economy of Intellectual Property. Routledge, 1996. ISBN 978-0813333045

- Brenkert, George G., and Tom L. Beauchamp (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of Business Ethics. Oxford University Press, 2012. ISBN 978-0199916221

- Burk, Dan L., and Mark A. Lemley. The Patent Crisis and How the Courts Can Solve It. University of Chicago Press, 2009. ISBN 978-0226080611

- Goldstein, Paul, and R. Anthony Reese. Copyright, Patent, Trademark and Related State Doctrines: Cases and Materials on the Law of Intellectual Property. Foundation Press, 2010. ISBN 978-1599417899

- Greenhalgh, Christine, and Mark Rogers. Innovation, Intellectual Property, and Economic Growth. New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 2010. ISBN 978-0691137988

- Griffiths, Ralph. The Monthly Review, Or, Literary Journal; Volume 61. Wentworth Press, 2019. ISBN 978-1012313951

- Hahn, Robert W. Intellectual Property Rights in Frontier Industries: Software and Biotechnology. AEI Press, 2005. ISBN 978-0844771915

- Jemielniak, Dariusz, and Aleksandra Przegalinska. Collaborative Society. The MIT Press, 2020. ISBN 978-0262537919

- Li, Xuan, and Carlos M. Correa (eds.). Intellectual Property Enforcement: International Perspectives. Edward Elgar Pub, 2009. ISBN 978-1848446526

- Lindberg, Van. Intellectual Property and Open Source: A Practical Guide to Protecting Code. O'Reilly Books, 2008. ISBN 978-0596517960

- Menell, Peter S., Mark A. Lemley, Robert P. Merges, and Shyamkrishna Balganesh. Intellectual Property in the New Technological Age. Clause 8 Publishing, 2020. ISBN 978-1945555152

- Miller, Arthur Raphael, and Michael H. Davis. Intellectual Property, Patents, Trademarks, and Copyright in a Nutshell. West Academic Publishing, 2012. ISBN 978-0314278340

- Nion, Alfred. Droits civils des auteurs, artistes et inventeurs (Civil rights of authors, artists and inventors). HardPress Publishing, 2019. ISBN 978-0371209462

- Perelman, Michael. Steal This Idea: Intellectual Property and The Corporate Confiscation of Creativity. Palgrave Macmillan, 2004. ISBN 978-1403967138

- Rand, Ayn. Capitalism: The Unknown Ideal. Signet, 1986. ISBN 978-0451147950

- Reisman, George. Capitalism: A Complete & Integrated Understanding of the Nature & Value of Human Economic Life. TJS Books, 2020. ISBN 978-1931089654

- Schechter, Roger E., and John R. Thomas. Intellectual Property: The Law of Copyrights, Patents and Trademarks. West Academic Publishing, 2003. ISBN 978-0314065995

- Sherman, Brad, and Lionel Bently. The Making of Modern Intellectual Property Law. Cambridge University Press, 1999. ISBN 978-0521563635

- Spinello, Richard A., and Maria Bottis. A Defense of Intellectual Property Rights. Edward Elgar Pub, 2009. ISBN 978-1847203953

- Spooner, Lysander. The Law of Intellectual Property. Anodos Books, 2018. ISBN 978-1725719620

- Stokes, Simon. Art and Copyright. Hart Publishing, 2001. ISBN 978-1841132259

- Vaidhyanathan, Siva. The Anarchist in the Library: How the Clash Between Freedom and Control Is Hacking the Real World and Crashing the System. New York: Basic Books, 2005. ISBN 978-0465089857

- Yu, Peter K. Intellectual Property and Information Wealth. Praeger, 2006. ISBN 978-0275988821

External links

All links retrieved November 30, 2024.

- What is Intellectual Property? WIPO

- Understanding Copyright and Related Rights WIPO

- Understanding Industrial Property WIPO

- Intellectual Property Legal Information Institute

- Intellectual Property Investopedia

- What Is Intellectual Property? LegalZoom

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.