| Part of the series on |

| Japanese mythology and folklore |

|

| Mythic texts |

* Kojiki

|

| Divinities |

| * Amaterasu

|

| Legendary creatures and urban legends |

| * Kitsune

|

| Mythical and sacred locations |

| * Mount Hiei

|

| Sacred objects |

* Amenonuhoko

|

| ShintÅ and Buddhism |

* Bon Festival

|

Japanese folklore is heavily influenced by the two primary religions of Japan, Shinto and Buddhism. Japanese mythology is a complex system of beliefs that also embraces Shinto and Buddhist traditions as well as agriculture-based folk religion. The Shinto pantheon alone boasts an uncountable number of kami (deities or spirits). One notable aspect of Japanese mythology is that it provided a creation story for Japan and attributed divine origins to the Japanese Imperial family, assigning them godhood. The Japanese word for the Emperor of Japan, tennÅ (天ç), means "heavenly emperor."

Japanese folklore has been influenced by foreign literature. Some stories of ancient India were influential in shaping Japanese stories, though Indian themes were greatly modified and adapted to appeal to the sensibilities of common people of Japan. [1][2] The monkey stories of Japanese folklore show the influence of both by the Sanskrit epic Ramayana and the Chinese classic The Journey to the West.[3] The stories mentioned in the Buddhist Jataka tales appears in a modified form in throughout the Japanese collection of popular stories.[4][5]

Japanese Folklore

Japanese folklore often involves humorous or bizarre characters and situations, and also includes an assortment of supernatural beings, such as bodhisattva, kami (gods and revered spirits), yÅkai (monster-spirits) (such as oni, similar to Western demons, ogres, and trolls), kappa (河童, "river-child," or gatarÅ, å·å¤ªé, "river-boy," or kawako, å·å, "river-child," a type of water sprite), and tengu (天ç, "heavenly dogs"), yÅ«rei (ghosts), Japanese dragons, and animals with supernatural powers such as the kitsune (fox), tanuki (raccoon dog), mujina (badger), and bakeneko (transforming cat).

Japanese folklore is often divided into several categories: "mukashibanashi," (tales of long-ago); "namidabanashi," (sad stories); "obakebanashi," (ghost stories); "ongaeshibanashi," (stories of repaying kindness); "tonchibanashi," (witty stories); "waraibanashi," (funny stories); and "yokubaribanashi," (stories of greed).

In the middle years of the twentieth century storytellers would often travel from town to town telling these stories with special paper illustrations called kamishibai.

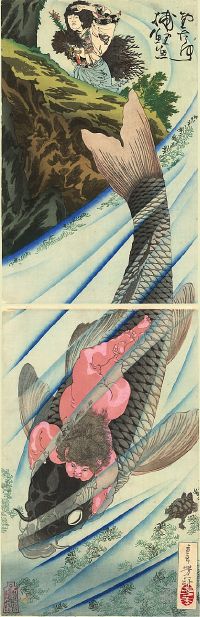

KintarÅ, the superhuman Golden Boy

A child of superhuman strength, Kintaro was raised by a mountain ogress on Mount Ashigara. He became friendly with the animals of the mountain, and later, he became Sakata no Kintoki, a warrior and loyal follower of Minamoto no Yorimitsu. It is a Japanese custom to put up a KintarÅ doll on Boy's Day, in the hope that the sons of the family will become equally brave and strong.

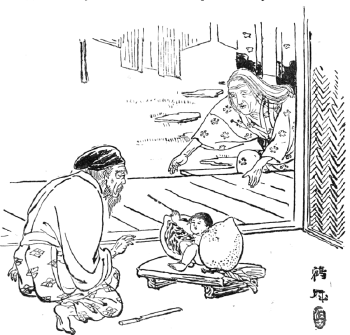

Issun-BÅshi, the One-inch Boy

An old couple lived alone and childless. The old woman wished to have a child, despite her old age, even if he was only one inch tall. Soon after, the old woman's wish was granted. They named the miniature child Issun-bÅshi ("One-Inch Boy"). The child, though he was incredibly small, was treated well by his parents. One day, the boy realized he would never grow taller than one inch, and went on a trip to seek his place in the world. Fancying himself a miniature samurai, Issun-bÅshi was given a sewing needle for a sword, a rice bowl boat, and chopsticks for oars.

He sailed down river to the city, where he petitioned for a job with the government and went to the home of a wealthy daimyo, whose daughter was an attractive princess. He was scorned for his small size, but was nevertheless given the job of accompanying the princess as her playmate. While they traveled together, they were suddenly attacked by an Oni (or an ogre in some translations). The boy defeated this demon using his needle, and the Oni dropped his magical Mallet of Luck. As a reward for his bravery, the princess used the power of the mallet to grow him to full size. Issun-bÅshi and the princess remained close companions and eventually wed.

MomotarÅ, the oni-slaying Peach Boy

His name literally means Peach TarÅ; as TarÅ is a common Japanese boy's name, it is often translated as Peach Boy. MomotarÅ is also the title of various books, films, and other works that portray the tale of this hero. According to the present form of the tale (dating to the Edo Period), MomotarÅ came to earth inside a giant peach, which was found floating down a river by an old, childless woman who was washing clothes there. The woman and her husband discovered the child when they tried to open the peach to eat it. The child explained that he had been sent by Heaven to be their son. The couple named him MomotarÅ, from momo (peach) and tarÅ (eldest son in the family).

Years later, MomotarÅ left his parents for an island called "Onigashima" to destroy the marauding oni (demons or ogres) that dwelt there. En route, MomotarÅ met and befriended a talking dog, monkey, and pheasant, who agreed to help him in his quest. At the island, MomotarÅ and his animal friends penetrated the demons' fort and beat the demons' leader, Ura, as well as his army, into surrendering. MomotarÅ returned home with his new friends, and his family lived comfortably from then on.

Urashima TarÅ, who visited the bottom of the sea

Urashima Taro was fishing one day when he spotted a turtle, which appeared to be in trouble. Urashima kindly saved the turtle, and I return, the turtle took Urashima to the Dragon Palace, deep underwater. There, Urashima met a lovely princess and spent a few days under the sea (the magic of the turtles had given him gills). However, he did not realize that time in the Dragon palace passed much more slowly than on the land, and that during those few days underwater, three hundred years had passed on land. When Urashima wanted to return to dry land, the princess gave him a box, containing his true age, but did not tell him what was inside. She instructed him never to open the box. When returned home, he found that all his family had died. Stricken with grief, he opened the box, which released a cloud of white smoke, causing Urashima to age and die.

Bunbuku Chagama, the shape-changing teakettle

âBunbuku Chagamaâ roughly translates to "happiness bubbling over like a tea pot." The story tells of a poor man who found a tanuki (raccoon dog) caught in a trap. Feeling sorry for the animal, he set it free. That night, the tanuki came to the poor man's house to thank him for his kindness. The tanuki transformed itself into a chagama and told the man to sell him for money. The man sold the tanuki-teapot to a monk, who brought it home and, after scrubbing it harshly, set it over the fire to boil water. Unable to stand the heat, the tanuki teapot sprouted legs and, in its half-transformed state, ran away.

The tanuki returned to the poor man with another idea. The man would set up a 'roadside attraction' (a little circus-like setup) and charge admission for people to see a teapot walking a tightrope. The plan worked, and each gained something good from the other; the man was no longer poor and the tanuki had a new friend and home.

Shita-kiri Suzume, "Tongue-Cut Sparrow,"

The story of a kind old man, his avaricious wife, and an injured sparrow. The story explores the effects of greed, friendship, and jealousy.

The Tale of the Bamboo Cutter

The story details the life of Kaguya-hime, a princess from the Moon who is discovered as a baby inside the stalk of a glowing bamboo plant. After she grows, her beauty attracts five suitors seeking her hand in marriage, whom she turns away by challenging them each with an impossible task; she later attracts the affection of the Emperor of Japan. At the tale's end, Kaguya-hime reveals her celestial origins and returns to the Moon.

The story of the vengeful Kiyohime, who became a serpent

Kiyohime (æ¸ å§«) is a character in the story of Anchin and Kiyohime. In this story, she fell in love with a Buddhist monk named Anchin, but after her interest in the monk was rejected, she chased after him and transformed into a serpent in a rage, before killing him in a bell where he had hidden in the DÅjÅ-ji temple.

BanchÅ Sarayashiki, the ghost story of Okiku and the Nine Plates.

BanchÅ Sarayashiki (çªçºç¿å±æ·, The Dish Mansion at BanchÅ) is a Japanese ghost story (kaidan) of broken trust and broken promises, leading to a dismal fate. According to the story, there was a beautiful servant named Okiku who worked for the samurai Aoyama Tessan. Okiku often refused him when he said he was in love with her and wanted to marry her, so he tricked her into believing that she had carelessly lost one of the family's ten precious Delft plates. Such a crime would normally result in her death. In a frenzy, she counted and recounted the nine plates many times. However, she could not find the tenth and went to Aoyama in guilty tears. The samurai offered to overlook the matter if she finally became his lover, but again she refused. Enraged, Aoyama threw her down a well to her death.

It is said that Okiku became a vengeful spirit (OnryÅ) who tormented her murderer by counting to nine and then making a terrible shriek to represent the missing tenth plate â or perhaps she had tormented herself and was still trying to find the tenth plate but cried out in agony when she never could. In some versions of the story, this torment continued until an exorcist or neighbor shouted "ten" in a loud voice at the end of her count. Her ghost, finally relieved that someone had found the plate for her, haunted the samurai no more.

Kachi-kachi Yama

Kachi-kachi is an onomatopoeia of the crackling sound a fire makes, and yama means "mountain," the rough translation is "Fire-Crackle Mountain," one of the few Japanese folktales in which a tanuki (raccoon-dog) is the villain, and confronts a heroic rabbit.

Hanasaka Jiisan

The story of the old man that made the flowers bloom. An old childless couple loved their dog. One day, it dug in the garden, and they found a box of gold pieces there. A neighbor thought the dog must be able to find treasure, and arranged to borrow the dog. When it dug in his garden, the dog uncovered only bones, and he killed it. He told the couple that the dog had just dropped dead. They grieved and buried it under the fig tree where they had found the treasure. One night, the dog's master dreamed that the dog told him to chop down the tree and make a mortar from it and pound rice in the mortar. He told his wife, who said they must do as the dog asked. When they did, the rice put into the mortar turned into gold. The neighbor borrowed the mortar, but his rice turned to foul-smelling berries, and he and his wife smashed and burned the mortar.

That night, in a dream, the dog told his master to take the ashes and sprinkle them on certain cherry trees. When he did, the cherry trees came into bloom, and the Daimyo (feudal lord), who was passing by, marveled at this and gave him many gifts. The neighbor tried to do the same, but his ashes blew into the Daimyo's eyes, so he threw him into prison; when he was released, his village would not let him live there anymore, and he could not, with his wicked ways, find a new home.

Japanese Mythology

Mainstream Japanese myths, as generally recognized today, are based on the Kojiki, Nihonshoki and some complementary books. The Kojiki or "Record of Ancient Things" is the oldest recognized book of myths, legends, and history of Japan. The Shintoshu, (ç¥éé), a Japanese mythological book regarding Shinto myths, explains origins of Japanese deities from a Buddhist perspective while the Hotsuma Tsutae (Hotuma Tsutaye or Hotuma Tsutahe, ç§çä¼) is an elaborate epic of Japanese mythical history which is substantially different from the mainstream version recorded in the Kojiki and the Nihon Shoki or Nihongi.

Note on Spelling of Proper Nouns

The deities of Japanese mythology have multiple aliases, and some of their names are so long that they can be tedious for the majority of readers. Below is a list of the most prominent names, and their abbreviated forms. Other abbreviated forms are also in use. For instance, Ninigi, or Ame-Nigishikuni-Nigishiamatsuhiko-Hikono-no-Ninigi-no-Mikoto in full, may also be abbreviated as Hikoho-no-Ninigi or Hono-Ninigi.

Proper names are sometimes written in a historical manner. In this article, underlined h, y, and w denote silent letters which are usually omitted from modern spelling. This underlining convention is peculiar to this article. Other syllables are modernized as follows (see also Japanese language). Note that some blend of these conventions is also often used.

- hu is modernized as fu.

- zi and di are modernized as ji. (distinction disappeared)

- zu and du are modernized as dzu. (distinction disappeared)

- oo is modernized as o or oh.

- For instance, various spellings of Ohonamudi include Ohonamuji, Oonamuji, Ohnamuji, and others.

For historical reasons, k, s, t, and h are sometimes confused with g, z, d, and b respectively.

- For instance, various spellings of Ohonamudi also include Ohonamuti and Ohonamuchi

Creation myth

The first gods summoned two divine beings into existence, the male Izanagi and the female Izanami, and charged them with creating the first land. To help them do this, Izanagi and Izanami were given a halberd decorated with jewels, named Amanonuhoko (Heavenly Halberd of the Marsh). The two deities then went to the bridge between heaven and earth, Amenoukihashi (Floating Bridge of Heaven) and churned the sea below with the halberd. When drops of salty water fell from the halberd, they formed into the island Onogoro (self-forming). Izanagi and Izanami descended from the bridge of heaven and made their home on the island. Eventually they wished to mate, so they built a pillar called Amenomihashira around which they built a palace called Yahirodono (the hall whose area is eight arms' length squared). Izanagi and Izanami circled the pillar in opposite directions, and when they met on the other side Izanami, the female deity, spoke first in greeting. Izanagi didn't think that this was proper, but they mated anyway. They had two children, Hiruko (watery child, Ebisu, (æµæ¯é , æµæ¯å¯¿, 夷, æ, Yebisu,) or Kotoshiro-nushi-no-kami, (äºä»£ä¸»ç¥), the Japanese god of fishermen, good luck, and workingmen, as well as the guardian of the health of small children and the only one of the Seven Gods of Fortune (ä¸ç¦ç¥, Shichifukujin) to originate from Japan; and Awashima (pale island) but they were badly-formed and are not considered deities.

They put the children into a boat and set them out to sea, and then petitioned the other gods for an answer as to what they had done wrong. They were told that the male deity should have spoken first in greeting during the ceremony. So Izanagi and Izanami went around the pillar again, and this time when they met Izanagi spoke first and their union was successful.

From their union were born the Åyashima, or the eight great islands of Japan:

- Awazi

- Iyo (later Shikoku)

- Ogi

- Tsukusi (later Kyūshū)

- Iki

- Tsushima

- Sado

- Yamato (later Honshū)

- Note that HokkaidÅ, Chishima, and Okinawa were not part of Japan in ancient times.

They bore six more islands and many deities. Izanami, however, died giving birth to the child Kagututi (incarnation of fire) or Ho-Masubi (causer of fire). She was then buried on Mount Hiba, at the border of the old provinces of Izumo and Hoki, near modern-day Yasugi of Shimane Prefecture. In anger, Izanagi killed Kagututi. His death also created dozens of deities.

The gods born from Izanagi and Izanami are symbolic of important aspects of nature and culture, but they are too many to mention here.

Yomi, the Shadowy Land of the Dead

Izanagi lamented the death of Izanami and undertook a journey to Yomi or "the shadowy land of the dead." Izanagi found little difference between Yomi and the land above, except for the eternal darkness. However, this suffocating darkness was enough to make him ache for the light and life above. Quickly, he searched for Izanami and found her. At first, Izanagi could not see her at all for the shadows hid her appearance well. Nevertheless, he asked her to return with him. Izanami spat out at him, informing Izanagi that he was too late. She had already eaten the food of the underworld and was now one with the land of the dead. She could no longer return to the surface with the living.

Izanagi was shocked at this news but he refused to give in to her wishes and leave her to the dark embrace of Yomi. Izanami agreed to go back to the world above, but first requested to have some time to rest and instructed Izanagi not to come into her bedroom. After a long wait, when Izanami did not come out of her bedroom, Izanagi was worried. While Izanami was sleeping, he took the comb that bound his long hair and set it alight as a torch. Under the sudden burst of light, he saw the horrid form of the once beautiful and graceful Izanami. She was now a rotting form of flesh with maggots and foul creatures running over her ravaged body.

Crying out loud, Izanagi could no longer control his fear and started to run, intending to return to the living and abandon his death-ridden wife. Izanami woke up shrieking and indignant and chased after him. Wild shikome, or foul women, also hunted for the frightened Izanagi, instructed by Izanami to bring him back.

Izanagi, thinking quickly, hurled down his headdress which became a bunch of black grapes. The shikome fell on these but continued pursuit. Next, Izanagi threw down his comb which became a clump of bamboo shoots. Now it was Yomi's creatures that began to give chase, but Izanagi urinated against a tree, creating a great river that increased his lead. Unfortunately, they still pursued Izanagi, forcing him to hurl peaches at them. He knew this would not delay them for long, but he was nearly free, for the boundary of Yomi was now close at hand.

Izanagi burst out of the entrance and quickly pushed a boulder in the mouth of the cavern that was the entrance of Yomi. Izanami screamed from behind this impenetrable barricade and told Izanagi that if he left her she would destroy 1,000 living people every day. He furiously replied he would give life to 1,500.

And so began the existence of Death, caused by the hands of the proud Izanami, the abandoned wife of Izanagi.

Sun, Moon, and Sea

As could be expected, Izanagi went on to purify himself after recovering from his descent to Yomi. As he undressed and removed the adornments of his body, each item he dropped to the ground formed a deity. Even more gods came into being when he went to the water to wash himself. The most important ones were created once he washed his face:

- Amaterasu (incarnation of the sun) from his left eye,

- Tsukuyomi (incarnation of the moon) from his right eye, and

- Susanoo (incarnation of storms and ruler of the sea) from his nose.

Izanagi divided the world among them, with Amaterasu inheriting the heavens, Tsukuyomi taking control of the night and moon and the storm god Susanoo owning the seas. In some versions of the myth, Susanoo rules not only the seas but also all elements of a storm, including snow and hail.

Amaterasu and Susanoo

Amaterasu, the powerful sun goddess of Japan, is the most well-known deity of Japanese mythology. Her feuding with her uncontrollable brother Susanoo, is equally infamous and appears in several tales. One story tells of Susanoo's wicked behavior toward Izanagi. Izanagi, tired of Susanoo's repeated complaints, banished him to Yomi. Susanoo grudgingly acquiesced, but had to attend to some unfinished business first. He went to Takamagahara (heaven, é«å¤©å, the dwelling place of the Kami, believed to be connected to the Earth by the bridge Ama-no uki-hashi, the "Floating Bridge of Heaven".) to bid farewell to his sister, Amaterasu. Amaterasu knew that her unpredictable brother did not have good intentions and prepared for battle. "For what purpose do you come here?" asked Amaterasu. "To say farewell," answered Susanoo.

But she did not believe him and requested a contest as proof of his good faith. A challenge was set as to who could bring forth more noble and divine children. Amaterasu made three women from Susanoo's sword, while Susanoo made five men from Amaterasu's ornament chain. Amaterasu claimed the title to the five men made from her belongings, and therefore, the three women were attributed to Susanoo.

Both gods declared themselves to be victorious. Amaterasu's insistence on her victory drove Susanoo to violent campaigns that reached their climax when he hurled a half-flayed pony, an animal sacred to Amaterasu, into Amatarasu's weaving hall, causing the death of one of her attendants. Amaterasu fled and hid in the cave called Iwayado. As the sun goddess disappeared into the cave, darkness covered the world.

All the gods and goddesses in their turn strove to coax Amaterasu out of the cave, but she ignored them all. Finally, the âkamiâ of merriment, Ama-no-Uzume, hatched a plan. She placed a large bronze mirror on a tree, facing Amaterasu's cave. Then Uzume clothed herself in flowers and leaves, overturned a washtub, and began to dance on it, drumming the tub with her feet. Finally, Uzume shed the leaves and flowers and danced naked. All the male gods roared with laughter, and Amaterasu became curious. When she peeked outside from her long stay in the dark, a ray of light called "dawn" escaped and Amaterasu was dazzled by her own reflection in the mirror. The god Ameno-Tajikarawo pulled her from the cave and it was sealed with a holy shirukume rope. Surrounded by merriment, Amaterasu's depression disappeared and she agreed to return her light to the world. Uzume was from then on known as the kami of dawn as well as mirth.

Susanoo and Orochi

Susanoo, exiled from heaven, came to Izumo Province (now part of Shimane Prefecture). It was not long before he met an old man and his wife sobbing beside their daughter. The old couple explained that they originally had eight daughters who were devoured, one by one each year, by the dragon named Yamata-no-orochi ("eight-forked serpent," who was said to originate from Kosiânow Hokuriku region). The terrible dragon had eight heads and eight tails, stretched over eight hills and was said to have eyes as red as good wine. Kusinada or Kushinada-Hime (rice paddy princess) was the last of the eight daughters.

Susanoo, who knew at once of the old couple's relation to the sun goddess Amaterasu, offered his assistance in return for their beautiful daughter's hand in marriage. The parents accepted and Susanoo transformed Kushinada into a comb and hid her safely in his hair. He also ordered a large fence-like barrier built around the house, eight gates opened in the fence, eight tables placed at each gate, eight casks placed on each table, and the casks filled with eight-times brewed rice wine.

Orochi arrived and found his path blocked; after boasting of his prowess he found that he could not get through the barrier. His keen sense of smell took in the sake - which Orochi loved - and the eight heads had a dilemma. They wanted to drink the delicious sake that called to them, yet the fence stood in their way, blocking any method of reaching it. One head first suggested they simply smash the barrier down...but that would knock over the sake and waste it. Another proposed they combine their fiery breath and burn the fence into ash, but then the sake would evaporate. The heads began searching for an opening and found the hatches. Eager for the sake, they were keen to poke their heads through and drink it. The eighth head, which was the wisest, warned his brethren of the folly of such a thing and volunteered to go through first to make sure all was well. Susanoo waited for his chance, letting the head drink some sake in safety and report back to the others that there was no danger. All eight heads plunged through one door each and greedily drank every last drop of the sake in the casks.

As the heads finished drinking, Susanoo launched his attack on Orochi. Drunken from consuming so much sake, the great serpent was no match for the spry Susanoo, who decapitated each head in turn and slew Orochi. A nearby river was said to have turned red with the blood of the defeated serpent. As Susanoo cut the dragon into pieces, he found an excellent sword from a tail of the dragon that his sword had been unable to cut. The sword was later presented to Amaterasu and named Ame no Murakumo no Tsurugi (later called Kusanagi). This sword was to feature prominently in many other tales.

Prince Ånamuji

Ånamuji (大å½ä¸», "Great Land Master,â also known as Åkuninushi) was a descendant of Susanoo. He was originally the ruler of Izumo Province, until he was replaced by Ninigi. In compensation, he was made ruler of the unseen world of spirits and magic. He is believed to be a god of nation-building, farming, business and medicine. He, along with his many brothers, competed for the hand of Princess Yakami of Inaba. While travelling from Izumo to Inaba to court her, the brothers met a skinned rabbit lying on a beach. Seeing this, they told the rabbit to bathe in the sea and dry in the wind at a high mountain. The rabbit believed them and thereby suffered in agony. Ånamuji, who was lagging behind his brothers, came and saw the rabbit in pain and instructed the rabbit to bathe in fresh water and be covered with powder of the "gama" (cattail) flower. The cured rabbit, who was in reality a deity, informed Ånamuji it was he who would marry Princess Yakami.

The trials of Ånamuji were many and he died twice at the hands of his jealous brothers. Each time he was saved by his mother Kusanda-hime. Pursued by his enemies, he ventured to Susanoo's realm where he met the vengeful god's daughter, Suseri-hime. The crafty Susanoo tested Ånamuji several times but in the end, Susanoo approved of the young boy and foretold his victory against his brothers.

Although the Yamato tradition attributes the creation of the Japanese islands to Izanagi and Izanami, the Izumo tradition claims Ånamuji, along with a dwarf god called Sukunabiko, contributed to or at least finished the creation of the islands of Japan.

Installation

Amaterasu ordered her grandson Ninigi (Ninigi no Mikoto, ççæµå°), the son of Ame no Oshihomimi no Mikoto and great-grandfather of Emperor Jimmu, to rule over the ground and plant rice, and gave him the Three Sacred Treasures:

- the magatama necklace of Magatama#Yasakani no Magatama|Yasakani no magatama (now situated in the Kokyo|imperial palace);

- the bronze mirror of Yata no kagami (now in the Grand Shrine of Ise); and

- the sword Kusanagi (a possible replica of which is now in Atsuta Shrine, Nagoya).

The first two were made to lure Amaterasu out of Amano-Iwato. The last was found in the tail of Orochi, an eight-headed dragon. Of these three, the mirror is the token of Amaterasu. The three together constitute the Imperial Regalia of Japan.

Ninigi and his company went down to the earth and came to Himuka, there he founded his palace.

Prosperity and Eternity

Ninigi met the Princess Konohana-sakuya (symbol of flowers), the daughter of Yamatumi (master of mountains), and they fell in love. Ninigi asked Yamatumi for his daughter's hand. The father was delighted and offered both of his daughters, Iwanaga (symbol of rocks) and Sakuya (symbol of flowers). But Ninigi married only Sakuya and refused Iwanaga.

Yamatumi said in regret, "Iwanaga is blessed with eternity and Sakuya with prosperity; because you refused Iwanaga, your life will be brief from now on." Because of this, Ninigi and his descendants became mortal.

Sakuya conceived by a night and Ninigi doubted her. To prove legitimacy of her children, Sakuya swore by her luck and took a chance; she set fire to her room when she had given birth to her three babies. By this, Ninigi knew her chastity. The names of the children were Hoderi, Hosuseri, and Howori.

Ebb and Flow

Hoderi lived by fishing in sea while his brother Howorilived by hunting in mountains. One day, Hooori asked his brother to swap places for a day. Hooori tried fishing, but he could not get a catch, and what was worse, he lost the fishhook he borrowed from his brother. Hoderi relentlessly accused his brother and did not accept his brother's apology.

While Hooori was sitting on a beach, sorely perplexed, Shihotuti told him to ride on a ship called the Manasikatuma and go wherever the current went. Following this advice, Hooori reached the house of Watatumi (Master of Seas), where he married Toyotama, the daughter of Watatumi. After three years of marriage, he remembered his brother and his fishhook, and told Watatumi about it.

Watatumi soon found the fishhook in the throat of a bream and handed it to Hooori. Watatumi also gave him two magical balls, Sihomitutama, which could cause a flood, and Sihohirutama, which could cause an ebb, and sent him off, along with his bride, to land.

As Toyotama was giving birth, she asked Hooori not to look at her delivery. However, Hooori, filled with curiosity, peeped in, and saw her transforming into a shark at the moment his son, Ugaya, was born. Aware of this, Toyotama disappeared into sea and did not return, but she entrusted her sister Tamayori with her yearning for Hooori.

Ugaya married his aunt Tamayori and had five children, including Ituse and Yamatobiko.

First Emperor

The first legendary emperor of Japan was Iwarebiko, posthumous known as âEmperor Jimmu,â who established the throne in 660 B.C.E. His pedigree is summarized as follows.

- Iwarebiko is a son of Ugaya and Tamayori.

- Ugaya is a son of Howori and Toyotama.

- Howori is a son of Ninigi and Sakuya.

- Ninigi is a son of Osihomimi and Akidusi.

- Osihomimi is born from an ornament of Amaterasu.

- Amaterasu is born from the left eye of Izanagi.

- Izanagi is born of his own accord.

Conquest of the East

Prince Yamatotakeru, originally Prince Ousu was a legendary prince of the Yamato dynasty, son of KeikÅ of Yamato, the legendary twelfth Tenno or Emperor of Japan. The tragic tale of this impressive figure is told in the Japanese chronicles Kojiki and Nihon Shoki. One of his sons later became Emperor Chuai, the fourteenth Emperor of Japan. His historical existence is uncertain. Details are different between the two books and the version in Kojiki is assumed to be loyal to the older form of this legend. Prince Ousu slew his elder brother Åusu, and his father, the emperor KeikÅ, feared his brutal temperament. The father plotted to have his son die in battle by sending him to the Izumo Province, (today the eastern part of the Shimane Prefecture) and the land of Kumaso, today Kumamoto Prefecture. But Ousu succeeded in defeating his enemies, in the latter case by dressing as a maid servant attendant at a drinking party (see image right). One of the enemies he defeated praised him and gave him the title Yamatotakeru, meaning The Brave of Yamato.

Emperor KeikÅs mind was unchanged, and he sent Yamato Takeru to the eastern land whose people disobeyed the imperial court. Yamatotakeru met his aunt Princess Yamato, the highest priestess of Amaterasu in Ise Province. His father attempted to kill him with his own hands, but Princess Yamato showed him compassion and lent him a holy sword named Kusanagi no tsurugi which Susanoo, the brother god of Amaterasu, had found in the body of the great serpent, Yamata no Orochi. Yamato Takeru went to the eastern land. He lost his wife Ototachibanahime during a storm, when she sacrificed herself to soothe the anger of the sea god. He defeated many enemies in the eastern land, and, according to legend, he and a local old man composed the first renga in the Kai Province, on the theme of Mount Tsukuba (now in Ibaraki Prefecture). On his return, he blasphemed a local god of Mount Ibuki, on the border of Åmi Province and Mino Province. The god cursed him with disease and he fell ill. Yamatotakeru died somewhere in the Ise Province. According to the legend the name of Mie Prefecture was derived from his final words. After death his soul turned into a great white bird and flew away. His tomb in Ise is known as the Mausoleum of the White Plover.

Notes

- â KyÅkai, Miraculous Stories from the Japanese Buddhist Tradition: The Nihon RyÅiki of the Monk KyÅkai (London: Routledge, 1997, ISBN 0700704493).

- â John L Brockington, The Sanskrit Epics (Leiden: Brill Academic Publishers, 1998, ISBN 9004026428), 514.

- â Gonul Pultar (ed.), On the Road to Baghdad Or Traveling Biculturalism: Theorizing a Bicultural Approach to⦠(Washington, DC: New Academia Publishing, LLC, 2005, ISBN 0976704218), 193.

- â Sushil Mittal, The Hindu World (London: Routledge, 2004, ISBN 0415215277), 93.

- â Tsuneko S. Sadao and Stephanie Wada, Discovering the Arts of Japan: A Historical Overview (Tokyo, Japan: Kodansha International, 2003, ISBN 477002939X), 41.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Brockington, John L. The Sanskrit Epics. Leiden: Brill Academic Publishers, 1998. ISBN 9004026428

- KyÅkai. Miraculous Stories from the Japanese Buddhist Tradition: The Nihon RyÅiki of the Monk KyÅkai. London: Routledge, 1997. ISBN 0700704493

- Mittal, Sushil. The Hindu World. London: Routledge, 2004. ISBN 0415215277

- Nakamura, KyÅko. Miraculous Stories from the Japanese Buddhist Tradition: The Nihon RyÅiki of the Monk KyÅkai. Surrey [England]: Curzon, 1997. ISBN 0700704493 ISBN 9780700704491

- Pultar, Gonul (ed.). On the Road to Baghdad Or Traveling Biculturalism: Theorizing a Bicultural Approach to..., 193. Washington, DC: New Academia Publishing, LLC., 2005. ISBN 0976704218

- Sadao, Tsuneko S., and Stephanie Wada. Discovering the Arts of Japan: A Historical Overview. Japan: Kodansha International, 2003. ISBN 477002939X

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

- Japanese_folklore history

- Japanese_mythology history

- Oni history

- Kappa_(folklore)Â history

- Tengu history

- KintarÅÂ history

- MomotarÅÂ history

- Urashima_TarÅÂ history

- Issun-BÅshi history

- Bunbuku_Chagama history

- Shita-kiri_Suzume history

- Hanasaka_Jiisan history

- Shintoshu history

- Hotsuma_Tsutae history

- Yamato_Takeru history

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.