Korean painting

Korean painting includes paintings made in Korea or by overseas Koreans on all surfaces, and art dating from the paintings on the walls of Goguryeo tombs to post-modern conceptual art using transient forms of light. Visual art produced on the Korean peninsula has been traditionally characterized by simplicity, spontaneity, and naturalism. Although Korean art was strongly influenced by Chinese art and the exchange of cultural influences between the two regions, unique developments occurred which reflected the political and social circumstances of the Korean people. The flourishing of Buddhism during the Goryeo period resulted in the production of quantities of religious paintings.

During the mid-to-late Joseon period, considered the Golden Age of Korean painting, Confucianism predominated. Korean painters produced landscapes depicting actual Korean scenery, and portrayals of Korean people in everyday activities. Scholar-painters also produced amateur works as a means of self-cultivation, and "minwha," paintings produced by anonymous folk artists, became popular. Suppression of Korean culture during the Japanese occupation and rapid modernization after World War II has resulted in traditional Korean media vanishing into an increasingly international style.

History

Generally the history of Korean painting is dated to approximately 108 C.E., when it first appears as an independent form. Little research has been done on the time period between those paintings and the frescoes that appear on the Goguryeo Dynasty tombs. Until the Joseon Dynasty, the primary influence on Korean art was Chinese painting, though the subject was Korean landscapes, facial features, and Buddhist topics, with an emphasis on celestial observation in keeping with the rapid development of Korean astronomy. Most of the earliest notable painters in Japan were either born in Korea or trained by Korean artists during the Baekje era, when Japan freely assimilated Korean culture.

Throughout the history of Korean painting, there has been a constant separation of monochromatic works of black brushwork, usually on mulberry paper or silk; and the colorful folk art or min-hwa, ritual arts, tomb paintings, and festival arts which demonstrated extensive use of color. This distinction was often class-based: scholars, particularly in Confucian art, felt that one could perceive color within the gradations of monochromatic paintings, and thought that the actual use of color coarsened the paintings and restricted the imagination. Korean folk art, and the painting of architectural frames, was seen as a means of brightening the exteriors of certain buildings, within the tradition of Chinese architecture, and showed early Buddhist influences of profuse rich thalo and primary colors inspired by the art of India.

One of the difficulties in examining Korean painting is the complications arising from the constant cultural exchanges between Korea and China, and Korea and Japan. In addition, frequent conflicts and foreign invasions resulted in the destruction of many works of art, and in the removal of others to foreign countries, where they are no longer able to be studied in context.

Although Korean art was strongly influenced by Chinese art, the periods during which the greatest artistic development occurred often do not coincide between the two regions. This is particularly evident in the wall paintings in Goguryeo tombs, Buddhist paintings of the Goryeo period, landscape painting in the first portion of the Joseon Dynasty and the landscapes painted of Korean scenes in the eighteenth century. Korean painting therefore was influenced by Chinese painting while still pursuing its own path.[1]

Genres and Subjects of Korean Painting

The genres of Buddhist art showing the Buddha, or Buddhist monks, and Confucian art portraying scholars in repose, or studying in quiet, often mountainous, surroundings, follow general Asian art trends.

Buddhas tend to have Korean facial features, and are in easy resting positions. Nimbus colors are not necessarily gold, and may be suggested by lighter colors. Faces are often realistic and show humanity and age. Drapery is depicted with great care. The face is generally two-dimensional, the drapery three-dimensional. As in medieval and renaissance western art, drapery and faces were done often by two or three artists who specialized in one particular skill. Iconography of Korean paintings follows Buddhist iconography.

Scholars in paintings tend to wear the traditional stove-pipe hats, or other rank hats, and scholar's monochromatic robes. Typically they are at rest in teahouses near mountains or at mountain lodges, or are pictured with their teachers or mentors.

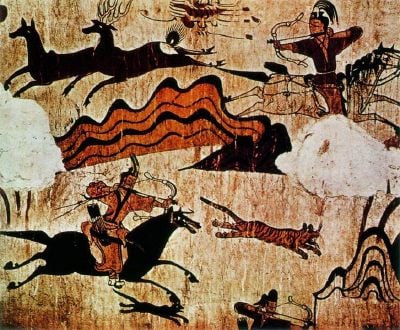

Hunting scenes, familiar throughout the entire world, are often seen in Korean courtly art, and are reminiscent of Mongolian and Persian hunting scenes. Wild boar, deer, and stags, and Siberian tigers were hunted.[1] Particularly lethal spears and spear-handled maces were used by horsemen within hunting grounds, after archers on the ground led the initial provocation of the animals as beaters.

During the Joseon period, landscape painters began to depict actual scenery rather than stylized imaginary scenes. Realism soon spread to other genres, and artists began to paint scenes of ordinary people and everyday Korean life. Portraits also became an important genre, as did amateur painting produced by the literati as a form of self-cultivation. Minwha, colorful decorative paintings produced by anonymous folk artists, were produced in large numbers.

Three Kingdoms Period

Each of the Three Kingdoms, Silla, Baekje, and Goguryeo, had its own unique painting style, influenced by the geographical region in China with which that particular kingdom had relations. Early Silla paintings, while said to be inferior in technique to those of Koguryo and Baekje, tended to be more fanciful and free-spirited, and some of them could almost be considered impressionistic. Baekje paintings did not lean toward realism and were more stylized, in an elegant free-flowing style. In marked contrast to the paintings of Shilla and Baekje, the paintings of Goguryeo were dynamic and often showed scenes of tigers fleeing archers on horseback. After Silla absorbed the other two kingdoms and became Unified Silla around 668, the three uniquely different painting styles merged into one, and were further influenced by continued contact between Silla and China.

Goguryeo (37 B.C.E. - 668 C.E.)

Except for several small Buddhist images, little remains of the religious art of Goguryeo. Goguryeo tomb murals date from around 500 C.E. The striking polychrome wall paintings, found on the walls of tombs from the Goguryeo Kingdom, exhibit a dynamism unique to Asian art of this early period. These magnificent, still strongly-colored murals depict daily life and Korean myths of the time. By 2005, seventy of these murals had been found, mostly in the Taedong river basin near Pyongyang, the Anak area in South Hwanghae province, and in Ji'an in China's Jilin province. China has claimed that these murals were painted by Chinese painters rather than Koreans, and this controversy still continues, despite the fact that the border was open and there was a constant migration of Korean artists abroad during that period.

Baekje Painters

The Baekje (Paekche) kingdom also produced notable tomb paintings. Baekje produced the most naturalistic and uniquely Korean Buddha images of the period, characterized by what has come to be known as the “Baekje smile.”

During the transitional period leading into the Joseon Dynasty many Buddhist painters left for Japan. Yi Su-mun (1400?-1450?) is highly important, and was a boat-companion of the older priest-painter, Shubun of Shokok-ji. According to Japanese tradition, Yi demonstrated so much skill in his "Catfish and Gourd" painting that Shogun Yoshimochi claimed him to be a son of the legendary Josetsu, as an adoptive honorific. Yi painted alongside and influenced the originators of Japanese Zen art; and was known in Japan by his Japanese name Ri Shubun or the Korean Bhubun. The development of Japanese Zen painting can thus be traced to Yi su-mun (Ri Shubun), alongside Josetsu and Sesshu, who was taught by Yi su-mun. The tradition of needle points in Japanese art began with Yi, and continued through his students, known as the Soga school, a more naturalistic group of artists than the courtly school patronized by the Ashikaga shoguns.

Goryeo Dynasty (918-1392)

During the Goryeo (Koryo) period (918-1392), painters proliferated as many aristocrats took up painting for intellectual stimulation, and the flourishing of Buddhism created a need for paintings with Buddhist motifs. Though elegant and refined, the Buddhist paintings of the Goryeo period might seem gaudy by today's standards. During the Goryeo era, artists began the practice of painting scenes based on their actual appearance, which became common later during the Chosun period.

During the Goryeo dynasty exceptionally beautiful paintings were produced in the service of Buddhism; paintings of the bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara (Korean: Gwaneum Bosal) are especially noted for their elegance and spirituality.

The murals of Horyu Temple, which are regarded as treasures in Japan, were painted by the Goryeo Korean monk, Damjing.

Yi Nyong and Yi Je-hyon are considered significant Goryeo artists outside of the Buddhist tradition.

Joseon Dynasty (1392–1910)

Joseon era paintings offer the richest variety and are the styles most imitated today. Some of these types of paintings existed during the earlier Three Kingdoms, and Koryo periods, but it was during the Joseon period that they became well-established.

The spread of Confucianism during the Joseon (Choson, Yi) period (1392–1910) stimulated a renewal of the arts. The decorative arts of that period in particular reveal a more spontaneous, indigenous sense than those of the Goryeo period. The decline of Buddhism as the dominant culture moved Korean painting in a more secular direction. Paintings of the Joseon period largely imitated northern Chinese painting styles, but certain painters attempted to develop a distinctly Korean approach, using non-Chinese techniques and painting Korean landscapes and scenes from Korean daily life. This sense of national identity was further strengthened by the Silhak, or practical learning movement, which emphasized understanding based on actual observations. The uniquely Korean element could also be seen in the stylized depiction of animals and plants.[2]

Buddhist art continued to be produced and appreciated, though no longer in an official context. The simplicity of Buddhist art was enjoyed in private homes and in the summer palaces of the Yi Dynasty. Goryeo styles evolved, and Buddhist iconography such as orchids, plum and chrysanthemum flowers, bamboo and knotted good luck symbols were incorporated in genre paintings. There was no real change in colors or forms, and imperial rulers did not attempt to impose any artistic standards.

Idealized works of the early Joseon Dynasty continued to follow Ming ideals and imported techniques. Until the end of the sixteenth century, court painters employed by an imperial Office of Painting followed the style of Chinese professional court painters. Famous painters of the period are An Kyon, Ch'oe Kyong, and Yi Sang-cha. At the same time, amateur scholar-painters painted traditional popular subjects such as birds, insects, flowers, animals, and the Buddhist “four gentlemen.” The paintings of the Chosun period can be generally categorized as landscape paintings, genre, Minhwa, the Four Gracious Plants, and portraits.

“Four Gentlemen”

The Four Gentlemanly Plants, or Four Gracious Plants, consist of plum blossoms, orchids or wild orchids, chrysanthemums, and bamboo. Originally they were Confucian symbols for the four qualities of a learned man: plum blossoms represented courage, bamboo represented integrity, the orchid stood for refinement, the chrysanthemum for a productive and fruitful life. More recently they have come to be associated with the four seasons: plums blossoms bloom in the early spring, orchids thrive in the heat of summer, chrysanthemums bloom in the late fall, and bamboo is green even in the winter.

Portraits

Portraits were painted throughout Korean history but were produced in greater numbers during the Chosun period. The main subjects of the portraits were kings, meritorious subjects, elderly officials, literati or aristocrats, women, and Buddhist monks.

Minhwa

Near the end of the Joseon period, corresponding to the growth of a merchant class in Korea, there was an emergence of minhwa (folk painting), a type of painting created by anonymous artisans who faithfully followed traditional forms. Intended to bring good luck to the owner’s household, the subjects of these paintings included the tiger (a mountain god), symbols of longevity such as cranes, deer, fungus, rocks, water, clouds, the Sun, the Moon, pine trees, and tortoises; paired birds symbolizing marital love; insects and flowers representing harmony between yin and yang; and bookshelves representing learning and wisdom. The subjects were depicted in a completely flat, symbolic, or even abstract, style, and in lively color.

Landscape and Genre Painting

”True-view”

Mid-dynasty painting styles moved towards increased realism. A national style of landscape painting called "true view" or “realistic landscape school” began, moving from the traditional Chinese style of idealized landscapes to paintings depicting particular locations exactly rendered. The practice of painting landscapes based on actual scenes, became more popular during the mid-Chosun period, when many painters traveled the countryside in search of beautiful scenery to paint. Mid-dynasty painters include Hwang Jip-jung (b. 1553).

Along with the interest in painting realistic landscapes surged came the practice of painting realistic scenes of ordinary people doing ordinary things. Genre painting, as this has come to be called, is the most uniquely Korean of all the painting styles and provides a historic look into the daily lives of the people of the Chosun period. Among the most notable of the genre painters was Kim Hong-do (1745-1818?) who left a large collection of paintings portraying many different scenes from Korea's past in vivid colors. Another of the great genre painters was Shin Yun-bok (1758-?), whose paintings of often-risqué scenes were both romantic and sensual. [2]

Golden Age

The mid- to late- Joseon Dynasty is considered the golden age of Korean painting. It coincided with the loss of contact with the collapsing Ming Dynasty, as the Manchu emperors took over China. Korean artists were forced to build new, nationalistic artistic models based on introspection and a search for particular Korean subjects. At this time Chinese influence ceased to predominate, and Korean art became increasingly distinctive.

The list of major painters is long, but the most notable names include:

- Jeong Seon (1676-1759), a literati painter influenced by the Wu school of the Ming Dynasty in China; much taken by the rugged peaks of Mount Kumgang (Diamond Mountain). To depict the rocky cliffs and soaring forests, he used characteristic forceful vertical lines.

- Yun Duseo (1668-1715), a face painter and portraitist

- Kim Hong-do (Danwon)(1745-1818?), who did highly colored crowded scenes of common and working class people in many natural work activities. His paintings have a post-card or photographic realism in a palette of whites, blues, and greens. There is little if any calligraphy in his works; but they have a sense of humor and variety of gestures and movement that make them highly imitated to this day. He was the first Korean painter to draw his themes from the activities of the lower classes. He also painted landscapes.

- Shin Yun-bok (1758-?), a court painter who did paintings, often of the scholarly or yangban classes in motion through stylized natural settings; he is famous for his strong reds and blues, and grayish mountainscapes.

Other important artists of the "literati school" include:

- Yi Kyong-yun

- Kang Se-hwang

International influences

Near the end of the Joseon period, Western and Japanese influences were becoming more evident. During the nineteenth century, shading was used for the first time in the painting of portraits. The styles of Chinese academic painting were dominant among professional painters such as Cho Chong-kyu, Ho Yu, Chang Sung-op, and Cho Soi-chin. Thre was also a brief revival of wen-jen hua, or Chinese literati painting, by a small group of artists including Kim Chong-hui, and Chon Ki.

Japanese influence

Japan first took Korea into its sphere of influence during the late 1800s, and formally annexed Korea with the Japan–Korea Treaty of 1910. Korean artists had a difficult time as Japan attempted to impose its own culture on all aspects of Korean life. Korean schools of art were closed, paintings of Korean subjects were destroyed, and artists were obliged to paint Japanese subjects in Japanese styles. Artists who remained loyal to Korean traditions had to work in hiding, and those who studied in Japan and painted in Japanese styles were accused of compromising. Among the noteworthy artists bridging the late Joseon dynasty and the Japanese occupation period was Chi Un-Yeong (1853-1936).

Western influence

In 1945, with Japan's surrender, Korean artists took on an increasingly international style. During the period following World War II, Korean painters assimilated Western approaches. Certain European artists with thick impasto technique and foregrounded brush strokes were the first to capture Korean interest. Such artists as Gauguin, Monticelli, Van Gogh, Cezanne, Pissarro, and Braque became highly influential, as they were the most taught in art schools, and books about them were quickly translated into Korean and made readily available. From these, modern Korean artists have drawn the tonal palettes of yellow ochre, cadmium yellow, Naples yellow, red earth, and sienna. Works are thickly painted, roughly stroked, and often show heavily textured canvases or thick pebbled handmade papers.

Elements central to Korean painting have been copied on a slightly larger scale by such western artists as Julian Schnabel, who paints in what appears to be large chunks of smashed ceramics. Western artists have been influenced by the Korean approach of translating a rich ceramic heritage into the brush strokes of oil painting.

Gallery

Geumgangjeondo, Landscape of Geumgangsan in Korea, painted by Jeong Seon. Ink and oriental watercolor on paper.

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Gabrielle Fahr-Becker, Sabine Hesemann, and Michael Dunn, The Art of East Asia (Könemann, 1999, ISBN 3829017456).

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 About Korean Paintings Korean Arts. Retrieved January 5, 2024.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Cho, Cha-yong, U-hwan Yi, and Cha-yong Cho. Traditional Korean painting a lost art rediscovered. Tokyo: Kodansha International, 1990. ISBN 9780870119972

- Fahr-Becker, Gabrielle, Sabine Hesemann, and Michael Dunn. The Art of East Asia. Könemann, 1999. ISBN 3829017456

- Lee, Sherman E., and Naomi Noble Richard. A history of Far Eastern art. New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1994. ISBN 0810934140

- Pratt, Keith L. Korean painting. Images of Asia. Hong Kong: Oxford University Press, 1995. ISBN 9780195858853

- Yi, Song-mi. Korean landscape painting continuity and innovation through the ages. Elizabeth, NJ: Hollym International Corp., 2006. ISBN 9781565912311

External links

All links retrieved January 5, 2024.

- About Korean Paintings Korean-Arts.

- Korean Art Art Institute of Chicago.

- Minhwa (Korean Folk Painting) Antique Alive.

- Mountain and Water: Korean Landscape Painting, 1400–1800 The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.