Kurt Koffka

Kurt Koffka (March 18, 1886 – November 22, 1941) was a German psychologist who, together with Max Wertheimer and Wolfgang Köhler, established Gestalt psychology. His work on perception showed that we perceive in terms of whole objects, which are greater than the sum of their parts. This challenged Wilhelm Wundt's mechanistic approach to experimental psychology, which had dominated German psychological research. The spokesperson for the Gestalt approach, Koffka moved to the United States, and was responsible for systematizing and advancing these ideas to the academic community. While his work has been overtaken in the fields of cognition and psychological development, Gestalt therapy has built upon his ideas in developing effective methods for promoting self-healing and personal growth.

Life

Kurt Koffka was born in Berlin, Germany, in 1886. He finished his early education under the guidance of his uncle, who evoked his interest in philosophy and science. Koffka attended Wilhelms Gymnasium, and later the University of Berlin, where he studied together with philosopher Alois Riehl. In 1904, he continued his studies at the University of Edinburgh in Scotland where he became familiar with British philosophy. Two years later he returned to Berlin, changing his major from philosophy to psychology.

Koffka became interested in human perception. One of his first published works was a study on his own color-blindness. He later completed his doctorate degree under Carl Stumpf at the University of Berlin, with work on the perception of musical and visual rhythms. Koffka married Mira Klein, who assisted him as his subject in this research.

In 1909, Koffka moved to the University of Freiburg to practice under the guidance of physiologist Johannes von Kries in the medical department. However, Koffka stayed in Freiburg only a short time, moving again a few years later. He became an assistant to Oswald Külpe and Karl Marbe at the University of Würzburg, which was one of the major centers of experimental psychology at the time.

In 1910, Koffka decided to leave Würzburg and continue his research at the Psychological Institute in Frankfurt am Main, under professor Friedrich Schumann. There he met Wolfgang Kohler, and that year they joined Max Wertheimer in his laboratory studying motion perception. The three of them became lifelong partners and together established the foundation for Gestalt psychology.

In 1911, Koffka left Frankfurt to become a lecturer at the University of Giessen, but he maintained a close relationship with Köhler and Wertheimer. The focus of his research now turned to thinking and memory. At the beginning of World War I, Koffka began his research on sound, working for the military. After the war, Koffka was granted a full-time position as professor of experimental psychology at the University of Giessen.

In 1921, he became director of the Psychology Institute at Giessen, where he established his own laboratory. Together with his students, and in cooperation with Köhler and Wertheimer, he published numerous articles on Gestalt psychology.

In 1922, Koffka published his ideas of Gestalt understanding of perception and its application to psychological development. His work quickly become extremely popular, and was translated into numerous languages under the title, The Growth of the Mind: An Introduction to Child Psychology. This work set up the foundation for many later theories in Developmental psychology. However, despite his sudden popularity, Koffka did not find favor among traditional German scholars. At the time, the majority of German psychologists opposed Gestalt ideas.

Koffka decided to move to the United States. His friend, American psychologist Robert Ogden, helped Koffka introduce the Gestalt point of view to the American audience, through a paper published in Psychological Bulletin in 1922. This was the beginning of a new phase in Koffka’s life.

In 1923, he divorced his wife and married Elisabeth Ahlgrimm. However, the marriage didn’t last long, and Koffka returned back to his first wife. From 1924 until 1927, he lectured at Cornell University and the University of Wisconsin, and in 1927, became a research professor at Smith College in Northampton, Massachusetts, where he stayed until his death. In 1928, Koffka again divorced his first wife and remarried his second wife, Elisabeth Ahlgrimm.

The years spent at Smith College were some of the most productive in Koffka’s life. In 1935 he summed up his research in the four-volume Smith College Studies in Psychology (1930-1933). In the same year, and after an unsuccessful research expedition to Uzbekistan, Koffka published his seminal work, for which he remains most famous, Principles of Gestalt Psychology. In it, Koffka summarized his life's hard work in the area of Gestalt psychology.

In 1939, he was invited to teach at Oxford University, where he extended his research to brain injuries. He worked with patients at the military hospital, developing an important method for evaluating brain damage.

In the next two years, Koffka started to experience serious health problems that limited his ability to do research. However, he returned to America and continued to teach at Smith College. He died in 1941 from a heart attack.

Work

Together with Wolfgang Kohler and Max Wertheimer, Koffka set the foundation for Gestalt psychology. They used the German word gestalt to describe their holistic approach to human experience. Gestalt is used in modern German to mean the way a thing has been gestellt or “put together.” There is no exact equivalent in English, with “form” and “shape” being the usual translations; the word is often rendered as “pattern” or “configuration” in psychology.

Their approach directly opposed the mechanistic psychology of the nineteenth century, which saw human experience in terms of separate sensations. Rather than focusing on the components of reality and reducing perception to its parts, as Wilhelm Wundt proposed, Koffka suggested that humans perceive whole configurations. Things around us—for example, a tree or a house—are seen as whole objects, not as a set of lines, colors, and other elements of which they are made.

Koffka claimed that the human mind naturally organizes individual sensations and experiences into meaningful wholes. In one of the first articles in English that Koffka wrote in 1922, he proposed his hypothesis of infant perception, saying that infants at first cannot distinguish individual objects, but perceive everything holistically. As they grow older, infants learn to discriminate and respond to individual objects. Thus, instead of building up meaning from separately perceived elements, Koffka suggested that we first perceive an impression of the whole environment and then gradually distinguish and separate out the distinct objects within it, often never noticing the individual elements that make up these objects.

At the beginning of his academic inquiry, Koffka studied movement phenomena and psychological aspects of rhythm. His early work combined elements of physiology and experimental psychology. When Koffka published his Principles of Gestalt Psychology in 1935, he tried to sum up all his research on perception and present the basic ideas of the Gestalt movement.

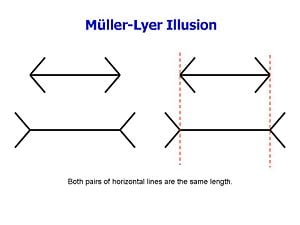

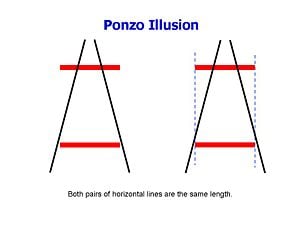

Koffka rejected the assumption in psychology that took for granted that veridical perception need not be explained. For example, until then, it had been thought that the perceptions of certain elements that comprise objects are fixed. In mathematics, a line that is three inches long will always be longer than a two-inch line. Psychologists assumed that such a line would also always look longer. Koffka, however, showed that when certain elements, like a three-inch line, are combined with other elements, our perception of those elements changes. Famous examples of this are the Ponzo and Müller-Lyer illusions. Koffka claimed psychologists always need to start with the question “Why do things look as they do?"

Koffka believed psychologists need to always look at the things holistically, in the context of where those things are located. The purpose of science in general, is not to simply collect facts, but to incorporate facts into a theoretical whole. Theoretical systems must incorporate all the facts and create a rational system. Since all the facts are interdependent, a successful theoretical system will not deny or neglect even the smallest fact. Koffka criticized scientists who created theoretical systems based on facts that fit into their system, while denying facts that did not fit. Koffka claimed that the Gestalt theoretical system takes all the facts into consideration. He challenged science to incorporate all the facts, from the mental, biological, and inanimate realms, into a comprehensive system.

One of the most important categories that science needs to take into account is order. Koffka held that among living things there is certain order, which cannot be seen on the inorganic level:

In inorganic nature you find nothing but the interplay of blind mechanical forces, but when you come to life you find order, and that means a new agency that directs the workings of inorganic nature, giving aim and direction and thereby order to its blind impulses (Koffka 1935: 16).

Koffka also suggested that science needs to take into account yet another category, Sinn, which can be translated as “meaning” or “ value.” Koffka believed that meaning and value should also be incorporated into scientific theories.

Legacy

Koffka, Kohler and Wertheimer created a new approach to psychology that directly opposed the Wundtian school that was dominant at the time. Koffka was the one who systematized their ideas into a coherent system of theories, Gestalt psychology. As the main spokesman of the Gestalt movement, he helped spread these ideas across Europe, and later into the United States.

Koffka also applied those ideas into practice, extending Gestalt theories into developmental psychology, especially in the areas of perception, learning, and cognition.

The principles of Gestalt psychology were later applied to more diverse areas in psychology, such as motivation, social psychology, and personality, particularly by Kurt Lewin.

Frederick Perls, a German-born psychiatrist, incorporated ideas from the Gestalt approach to perception into his Gestalt therapy, postulating that healthy persons naturally organize their experiences into well-defined needs, or "Gestalts," to which they respond appropriately. This form of therapy helps clients to deal with incomplete Gestalts, by becoming aware of significant aspects of their experiences and integrating them into completed wholes, to which they can then develop appropriate responses.

Bibliography

- Koffka, K. (1922). "Perception: An introduction to the Gestalt-theory." Psychological Bulletin, 19, 531-585.

- Koffka, K. (1924). The Growth of the Mind. (R. M. Ogden, Trans.). London: Routledge & Kegan Paul. (Original work published 1921). (Reissued, Transaction Publishers, 1980). ISBN 0878557849

- Koffka, K. (1935). Principles of Gestalt psychology. New York: Harcourt, Brace, & World.

External links

All links retrieved June 16, 2018.

- Gestalt psychology website of the international Society for Gestalt Theory and its Applications - GTA

- Website on gestalt psychology with biographies of Wertheimer et al.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.