Laotian art

Except for modern and contemporary visual arts, Lao artistic traditions developed around religion and the political and social circumstances that governed the lives of the various ethnic groups in Laos. Many of these traditions, particularly sculpture, music, and classical dance, were strongly influenced by the Khmer, Vietnam, and Thailand civilizations. The physical artistic heritage of Laos encompasses archaeological sites, religious monuments and cultural landscapes, traditional towns and villages, and a variety of highly-developed crafts including textiles, wood carving, and basket-weaving. The two great performing art traditions of Laos are rich and diverse folk heritage of the lam or khap call-and-response folk song and its popular theatrical derivative lam luang; and the graceful classical music and dance (natasinh) of the former royal courts.

Little is known about the earliest cultures in the region. The Plain of Jars, a large group of historic cultural sites, containing thousands of large stone jars, which archaeologists believe were used 1,500–2,000 years ago by an ancient Mon-Khmer race. Recently discovered kiln sites in the Vientiane area indicate an active involvement with ceramics manufacture and artistry during the fifteenth to the seventeenth centuries. The influence of Theravada Buddhism is reflected throughout Laos in its language as well as in art, literature, and the performing arts. Buddhist sculptures and paintings make up a large portion of the enduring artistic tradition of Laos.

Buddhist sculpture

The earliest Buddha images in present-day Laos are those of the Mon and Khmer kingdoms of the first millennium C.E. Dvaravati-style Mon Buddha images can be seen carved into the rock face at Vangxang, north of Vientiane, and several Mon and Khmer Buddha sculptures recovered from the central and southern provinces are exhibited in museums. The earliest indigenous Buddha images, dating from 1353-1500, show a strong Khmer influence, but by the reign of King Wisunarath (1501-1520), a distinctive Lao style had begun to develop, and statues displayed characteristic beak-like noses, extended earlobes, tightly-curled hair, and long hands and fingers. During this period, two distinctive mudras (hand positions), found only in Lao Buddhist sculpture, appeared: "Calling for Rain," in which the Buddha stands with both arms held stiffly at the side of the body with fingers pointing downwards, and "Contemplating the Tree of Enlightenment" in which the Buddha stands with hands crossed at the wrist in front of the body.[1]

Many magnificent examples from the "golden age" of the Lao Buddha image, the period from 1500-1695, can be seen today in Ho Phra Keo, Wat Sisakhet and the Luang Prabang National Museum. With the growth of Siamese influence in the region during the 18th century, Lao sculpture was increasingly influenced by the contemporaneous Ayutthaya and Bangkok (Rattanakosin) styles. By the French colonial period decline had set in, and Buddha images were cast less and less frequently.

Lao artisans used a variety of media in their sculptures, including bronze, wood, ceramics, gold, and silver and precious stones. Smaller images were often cast in gold or silver or made of precious stone, while the tiny, votive images found in cloisters or caves were made of wood and ceramics. Wood was also commonly used for large, life-size standing images of the Buddha.

The Pak Ou (mouth of the Ou river) caves near Luang Prabang, Laos, are noted for their hundreds of mostly wooden Lao style Buddha sculptures assembled over the centuries by local people and pilgrims and laid out over the floors and wall shelves.

A few large images were cast in gold, most notably the Phra Say of the sixteenth century, which the Siamese carried to Thailand in the late eighteenth century. Today, it is in enshrined at Wat Po Chai in Nongkhai, Thailand, just across the Mekong River from Vientiane. The Phra Say's two companion images, the Phra Seum and Phra Souk, are also in Thailand, in Bangkok and Lopburi. Perhaps the most famous sculpture in Laos, the Phra Bang, is also cast in gold. According to legend, the craftsmanship is held to be of Sinhalese origin, but the features are clearly Khmer. Tradition maintains that relics of the Buddha are contained in the image.

The two best-known sculptures carved in semi-precious stone are the Phra Keo (The Emerald Buddha) and the Phra Phuttha Butsavarat. The Phra Keo, which is probably of Xieng Sen (Chiang Saen, Lannathai) origin, carved from a solid block of jade, rested in Vientiane for two hundred years before the Siamese carried it away in the late eighteenth century. Today, it serves as the palladium of the Kingdom of Thailand, and resides at the Grand Palace in Bangkok. The Phra Phuttha Butsavarat, like the Phra Keo, is also enshrined in its own chapel at the Grand Palace in Bangkok. Before the Siamese seized it in the early nineteenth century, this crystal image was the palladium of the Lao kingdom of Champassack.

Brick-and-mortar was also used to construct colossal Buddha images. Perhaps the most famous of these is the image of Phya Vat (sixteenth century) in Vientiane, though an unfortunate renovation altered the appearance of the sculpture, and it no longer resembles a Lao Buddha.

Bronze sculptures

Bronze is an alloy of copper, containing about two percent tin. Other materials are often added, however, and the balance of ingredients determines the characteristics of the bronze. In Laos, like Cambodia and Thailand, the bronze, which is called samrit, includes precious metals, and often has a relatively high percentage of tin, which gives the newly-cast images a lustrous dark gray color. Other images, such as the Buddha of Vat Chantabouri in Vientiane, have a higher copper and, probably, gold content that give them a muted gold color.

A number of colossal bronze images exist in Laos. Most notable of these are the Phra Ong Teu (sixteenth century) of Vientiane, the Phra Ong Teu of Sam Neua, the image at Vat Chantabouri (sixteenth century) in Vientiane and the image at Vat Manorom (fourteenth century) in Luang Phrabang, which seems to be the oldest of the colossal sculptures. The Manorom Buddha, of which only the head and torso remain, shows that colossal bronzes were cast in parts and assembled in place.

The religious art tradition of the region has received an original contemporary twist in the monumental fantastic sculpture gardens of Luang Pu Bunleua Sulilat: Buddha Park near Vientiane, and Sala Keoku near Nong Khai, Thailand.

Buddhist painting

Two forms of Buddhist painting, bas-relief murals and painted preaching cloths, were primarily created for use in educational purposes and as aids in meditation. Images from the Jataka, the Lao version of the Ramayana known as the Pharak Pharam, and other religious themes, were painted without perspective using simple lines and blocks of uniform color, with no shadow or shading. The Buddha and other important figures were depicted following strict artistic conventions. Lao temple murals were painted directly onto dry stucco, making them extremely fragile and susceptible to flaking. Those which are still in existence have been restored many times, often using modern pigments; examples can be seen at Wat Sisakhet in Vientiane and at Wat Pa Heuk and Wat Siphouthabath in Luang Prabang. Hanging cloths made by painting scenes from the Jataka or Pharak Pharam onto rough cotton sheets were displayed while monks were preaching.[2]

Luang Prabang, the site of numerous Buddhist temple complexes, was declared a United Nations World Heritage Site in December 1995. The Cultural Survival and Revival in the Buddhist Sangha Project was launched to revive the traditional skills needed to properly care for, preserve and conserve temples by establishing a training school to teach young monks painting, gilding and woodcarving.[3]

Ceramics

The discovery of the remains of a kiln in 1970 at a construction site in the Vientiane area brought to light a tradition of Laotian ceramics. Since then, at least four more kilns have been identified and surface evidence and topography indicate at least one hundred more in the Ban Tao Hai (Village of the Jar Kilns) vicinity. Archaeologists have labeled the area Sisattanak Kiln Site.

According to Honda and Shimozu (The Beauty of Fired Clay: Ceramics from Burma, Cambodia, Laos, and Thailand, 1997), the Lao kilns are similar to the Siamese types found at Suphanburi and Si Satchanalai. But Hein, Barbetti and Sayavongkhamdy[4] say that the Lao kilns, which are of a cross-draft clay-slab type, differ substantially not only from the Siamese types but all other types in Southeast Asia.

Radiocarbon dating of the kiln gives a fifteenth-seventeenth century time frame, with an earlier period of that range most likely. This is supported by the evidence of surface finds, which indicate that an increasing number of glazed wares were fired over time. Older wares were of a utilitarian nature, including pipes, domestic wares and architectural fittings. Most of the glazed wares were pipes; their quality indicates a well-developed tradition, and their motifs suggest the possibility that they were export wares.

Much study remains to be done, but the site is evidence that Lao ceramic production was comparable to that of other countries in the region. From the examples collected to date, it can be said that Lao ceramics used one kind of clay, with 5 percent quartz added as a temper. Both the clay and the quartz were finely crushed. The glazed wares were a light, translucent green (like celadon) or various shades of brown. There have also been shards showing an olive-colored glaze, not unlike the type found in Thailand.

Many of the glazed wares have ribbed or fluted exteriors, similar to that of the silver bowls ubiquitous in Laos, both the regular silver bowls ("oh tum") and the silver stem bowls ("khan"). Glazed ceramic stem bowls have been collected as surface finds at the Sisattanak Kiln Site. Decorations to glazed wares show a great measure of restraint, with simple incisions, stamps and fluting. Unglazed wares are similarly austere. They are generally not decorated with incisions or stamps, which are common in other Southeast Asian wares.

Textiles and crafts

Silk and cotton cloth is hand-woven on traditional wooden frame looms by the ethnic Lao and most other Tai-speaking ethnicities to create wrap-round skirts with elaborately bordered hems (pha sin), ceremonial shawls (pha biang), shoulder bags and many other articles of Lao traditional clothing. Textiles are produced in many different styles and dyed in a range of different colors according to the geographical provenance and ethnicity of the weavers. Various regional styles may be identified, including the solid color and striped pattern mix of northern chok, supplementary thread silk textiles, and the Khmer-style pha chongkraben of the southern provinces. Motifs vary from region to region, but the use of gold and silver threads and protective diamond- and star-shaped designs and images of mythical animals such as dragons and nagas are common to many parts of the country. In recent years the migration of many provincial weaving families to Vientiane to seek employment there has led to the evolution of a new, modern style of Lao textile which includes both regional and international designs.

Traditional weaving techniques handed down from one generation to the next include chok (discontinuous supplementary weft technique), khit (continuous supplementary weft technique), mat mi (resist-dyeing technique), ghot (tapestry weave technique), muk (continuous supplementary warp technique) and muko (a combination of the muk, mat mi and chok techniques).

Hmong, Yao, and Sino-Tibetan ethnicities such as the Lolo-Burmish speaking Akha, Ha Nhi, Lolo and Phunoi are known for their sewing and embroidering skills, which have given rise to some of the most spectacular and colorful traditional costumes in the world. In many parts of the country these colorful costumes are decorated with copious amounts of silver jewelry. Silver smithing is still practiced by a number of ethnic groups, predominantly by the Hmong, the Yao and Tibeto-Burman ethnicities such as the Akha, but also by some Mon-Khmer groups in the southern half of the country. Several ethnicities still utilize bronze drums in their religious ceremonies, though in many areas the art of casting these drums is dying out.

Paper has been made by hand in Laos for over 700 years using the bark of the local sa or mulberry tree (broussonetia papyrifera vent). The bark is crushed and soaked in water until it had dissolved into a paste. The liquid is then scooped out, poured through a bamboo sieve and finally placed in a thin layer on a bamboo bed and dried in the sun. Traditionally sa paper was used for calligraphy and for making festive temple decorations, umbrellas, fans and kites. In former times it was also used as a filter in the manufacture of lacquer ware. In recent years the art of sa paper handicraft has been revived, particularly in Luang Prabang where it is now used to create lampshades, writing paper, greetings cards and bookmarks.

The manufacture of household objects such as baskets, containers and furniture from bamboo, rattan and various other types of reed has been practiced for centuries. Woodcarving was traditionally a sculptural art, and with the spread of Buddhism it assumed an increasingly important role in the production of Buddha images and the carving of temple and palace door frames, pillars, roofs, lintels and decorative friezes. During the Lan Xang era skilled carpenters produced royal thrones, ornate wooden furniture, royal barges, palanquins and elephant howdahs. By the early twentieth century, their work had expanded to include the production of high-quality tables, chairs and cabinets for a growing urban middle class.

Architecture

In the rural and mountainous districts of Laos, most ethnic minority groups live in small or medium-sized villages of stilted or non-stilted thatched houses constructed from wood and bamboo. The residential housing of Tai-Kadai ethnicities varies in size and quality; many Northern Tai ethnicities construct rudimentary single-roomed bamboo houses on stilts, but South Western Tai groups such as the Tai Daeng, Tai Dam, and Tai Khao build large open plan stilted houses with tortoise shell-shaped thatched roofs. Lao Isaan, Lao Ngaew and a few South Western Tai groups such as the Kalom and Phu Tai live mainly in houses of traditional Lao design. In the past several Mon-Khmer ethnicities, including the Bahnaric-speaking Brau, Sedang and Yae, the Katuic-speaking Ca-tu, Katang, Kui, Pa-co and Ta-oi and Lavy, constructed stilted long houses up to 30 or 40 meters in length, to house numerous extended families. Bahnaric and Katuic long houses were traditionally clustered around a communal house, where ritual ceremonies were performed, guests received and village councils held. Sometimes the communal house took the imposing form of a rong house, characterized by a high ground clearance and steep two- or four-sided roof with sculpted finials. Today residential long houses and tall-roofed communal houses still exist, but over the past half-century communal house design has become simpler and there has been a trend towards the construction of smaller, single-family stilted houses of bamboo and wood, grouped in clusters of 20 to 100.[5]

Contemporary visual arts

Western-style oil and water-color painting arrived in Laos during the French colonial period. The first Western art school was opened by the French painter Marc Leguay (1910-2001), who taught traditional drawing, metalwork and graphic art there from 1940 to 1945, and later taught art at the Lycée de Vientiane until 1975. Marc Leguay portrayed scenes of Lao life in vibrant colors and is chiefly remembered for the postage stamp designs he produced on commission to the Royal Lao Government during the 1950s.

Leguay was also involved in the founding of the National School of Fine Arts (now the National Faculty of Fine Arts) under the Ministry of Education, Sport and Religious Affairs, which opened in 1962, together with the National School of Music and Dance at Ban Anou in central Vientiane. After 1975 two provincial secondary art schools were established in Luang Prabang and Savannakhet, and a National Arts Teacher Training School was also opened in 1982. Since the syllabus has always focused mainly on copying classical or early modern Western masters, and Laos has remained relatively insulated from contemporary international art trends and developments, a distinctive Lao style of contemporary art has yet to develop. There is little market within Laos for contemporary art. Established Lao painters and sculptors are obliged to support themselves by creating realistic landscapes and scenes for the tourist market. There are at least two well-known overseas Lao artists, Vong Phaophanit (b. 1961), who combines indigenous materials such as rice, rubber, and bamboo with a striking use of neon light; and Phet Cash (b. 1973), who does botanical drawings and modern abstract paintings.[6]

Performing arts

Lao performing arts, like many Asian artistic traditions, have their roots in ancient religious and community activities. Communication with the spirits has always been an element of Lao daily life, and both the ethnic Lao and many minority groups continue to perform ritual dances of propitiation in many parts of the country. A well-known animistic dance ritual associated with the Phou Nheu and Nha Nheu guardian deities of Luang Prabang takes place every Lao New Year at Wat Wisun in the northern capital. Healing rituals also have ancient roots; the Lao folk genres lam saravane and lam siphandone (call-and-response folk songs) still incorporate healing dances of spirit propitiation (lam phi fah), performed by female shamans.

The art of sung storytelling traditionally served to teach morality as well as perpetuating the various myths, legends, and cosmologies associated with particular ethnic groups. As Buddhism spread throughout the region, monks used sung storytelling techniques to recite Jataka tales and other religious texts inscribed on palm-leaf manuscripts. The term an nangsu (literally "reading a book") is still widely used to describe the sung storytelling genre. Lam pheun, one of the older varieties of the call-and-response genre lam/khap, involves the recitation of Jataka tales, local legends, and histories, while the regional lam siphandone features long slow passages of solo recitation believed to derive from a much earlier period.

The two great performing arts traditions of Laos are rich and diverse folk heritage of the lam or khap call-and-response folk song and its popular theatrical derivative lam luang; and the graceful classical music and dance (natasinh) of the former royal courts.[7]

Classical music

The Lao term "peng lao deum" (traditional lao pieces") makes a distinction between classical court music (mainly of Luang Prabang) and the nonclassical folk traditions, but historical evidence points to an indigenous classical tradition heavily influenced by ancient Khmer music. King Fa Ngum was raised and educated in Angkor Wat, and brought Khmer traditions with him when he founded the kingdom of Lan Xang in 1353 and established the first center for court music. In 1828, the Siamese established control over the region and slowly infiltrated the musical traditions of the court.

Lao classical music is closely related to Siamese classical music. The Lao classical orchestra (known as a piphat) can be divided into two categories, Sep Nyai and Sep Noi (or Mahori). The Sep Nyai orchestra performs ceremonial and formal music and includes: Two sets of gongs (kong vong), a xylophone (lanat), an oboe (pei or salai), two large kettle drums (khlong) and two sets of cymbals (xing). The Sep Noi, capable of playing popular tunes, includes two bowed string instruments, the So U and the So I, also known to the Indians. These instruments have a long neck or fingerboard and a small sound box; this sound box is made of bamboo in the So U and from a coconut in the So I. Both instruments have two strings, and the bow is slid between these two strings, which are tuned at a fifth apart and lways played together. The Sep Nyai is strictly percussion and oboe; the Sep Noi ensemble (or Mahori) may include several khene. In this respect, the Sep Noi differs markedly from the mahori orchestras of Cambodia and Siam.

Classical court music disappeared from Laos after the communist takeover in 1975. The Royal Lao Orchestra, consisting of musicians of the former court of the king of Laos, moved to Knoxville and Nashville, Tennessee, in the United States, and tried to continue the tradition of classical court music there.[8] The communist government regarded classical court music as “elitist” and integrated the khene into the piphat to give it a uniquely Lao flavor. The modified ensemble was given the name “mahori,” a term previously used in Thailand and Cambodia for an ensemble dominated by stringed instruments which performed at weddings and other community celebrations; its new usage was intended to reflect the role of the modified piphat as an ensemble for the entertainment of all the people.

Some ethnomusicologists believe that the ancient musical traditions of the Khmer people as well as diverse forms of folk music related to the oldest types of Indian music, which have largely disappeared in India itself, have been best preserved in Laos. They claim that a a tempered heptatonic scale, known by ancient Hindus as the "celestial scale" (Gandhara grama), which divides the octave into seven equal parts, is used in the classical music of Laos.

Classical dance

The rulers of Lan Xang (14th century) introduced the Khmer god-king ideology and the use of sacred female court dancers and masked male dancers, accompanied by gong-chime ensembles, to affirm the divinity of the king and protect him from evil influences. By at least the 16th century, a Lao version of the Ramayana known as the Pharak Pharam had been commissioned to serve as source material.

In subsequent centuries, as Lan Xang broke up into the smaller kingdoms of Luang Prabang, Vientiane and Champassak, the court theater of Siam, also based on the Khmer model but steadily developing its own unique characteristics, became the source of artistic inspiration for the Lao courts, as shown by the close affinities between the styles and repertoires of the surviving classical dance troupes of Vientiane and Luang Prabang.

Stylistically, the classical dance (lakhon prarak pharam) of today, accompanied by the mahori ensemble, is very similar to its Siamese counterpart, featuring both the female dance (lakhon nai) and male masked dance (khon). However, its source, the Pharak Pharam, contains characteristically strong Buddhist elements and also differs in a number of details from both Siamese and other Southeast Asian versions of the Ramayana epic.[9]

Folk music and dance

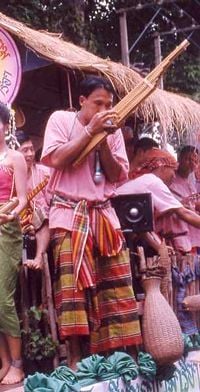

Many of Laos' ethnic minority groups preserve distinctive music and dance traditions, which are performed to propitiate the spirits and celebrate social milestones in the lives of members of the community. Solo and group songs and dances are accompanied by a variety of instruments: stringed instruments ranging from plucked gourd lutes to bowed bamboo fiddles; percussion instruments of various shapes and sizes, including bronze drums and gongs, wooden bells, bamboo clappers, chimes, and even pestles and mortars; and wind instruments such as vertical and transverse bamboo flutes, single- and double-reed wooden trumpets and buffalo horns. The most ubiquitous wind instrument in Laos is the khene, which is used not just by the Lao ethnic majority but also by many other Tay-Tai speaking groups. Bronze drums carry great ritual significance in the wider Southeast Asian region, and in Laos, as in neighboring Vietnam and Cambodia, they constitute an integral part of ritual ceremonies amongst Mon-Khmer and Lolo-Burmish groups.[10]

The Lao folkloric tradition incorporates a wide repertoire of folk dances (fon phun muang), some based on ancient animist rituals, some developed in celebration of the passing of the seasons and others adapted from courtly performance genres. Many different varieties of ethnic minority folkloric dance are performed in Laos, including the xoe and sap (bamboo pole) dances of the Tay-Tay speaking groups to the robam of the Khmer, the khene and umbrella dances of the Hmong and the bell and drum dances of the Yao. One of the most popular social dances in Laos is the celebrated lam vong (circle dance), in which couples dance circles around one another until there are three circles in all—a circle danced by the individual, a circle danced by the couple, and a circle danced by the whole crowd. Featuring delicate and precise movements of the hand, the lam vong is danced to a slow rhythm performed by an ensemble led by the khene. Often performed along with the recital of a traditional Lao greetings poem, the fon uay phone welcoming dance originated in the royal palace. Similar courtly origins are attributed to the fon sithone manora (which depicts the romantic tale of the eponymous half-bird, half-human heroine), fon sang sinxay (based on the Sinxay epic) and the candle dance fon tian, which is believed to have originated in neighboring Lanna. Other important folk dances include the welcoming dance fon baci su khuan which is performed in conjunction with the baci ceremony, the graceful southern female dance fon tangwai (performed to the accompaniment of lam tangwai), and the male martial arts dance fon dab. Well-known ethnic minority dances include the Hmong New Year dance, fon bun kin chieng and the Khmu courtship dance fon pao bang.[11]

Lao folk music, known as lam (khap in the north), a unique call-and-response singing style which derives its melodies from word tones, is believed to be a direct legacy of the pre-Buddhist era of spirit communication and epic recitation. The extemporaneous singing, accompanied by the khene is popular both in Laos and Thailand, where there is a large ethnic Lao population.

In Traditional Music of the Lao, Terry Miller identifies five factors which helped to produce the various genres of lam: Animism (lam phi fa), Buddhism (an nangsue), story telling (lam phuen), ritual courtship, and male-female competitive folksongs (lam glawn).[12] Of these, lam phi fa and lam phuen are probably the oldest, while mor lam glawn was the primary ancestor of the commercial mor lam performed today. Glawn or gaun (Thai กลอน) is a verse form commonly used in traditional mor lam, made up of four-line stanzas, each with seven basic syllables (although sung glawn often includes extra, unstressed syllables). There is a set pattern for the tone marks to be used at various points in the stanza, plus rhyme schemes to hold the unit together. Performances of glawn are typically memorized rather than improvised.[13] The characteristic feature of lam singing is the use of a flexible melody which is tailored to the tones of the words in the text.

Lam pheun, one of the most popular varieties of the call-and-response genre lam (khap), involves the recitation of jataka tales, local legends and histories, while the regional lam siphandone features long slow passages of solo recitation believed to derive from a much earlier period. Modern lam (khap) is best-known for its raucous and often bawdy exchanges between men and women. Lam pa nyah (literally 'poetry lam'), a flirtatious male-female courting game in which young men and women engage in sung poetic dialog, testing each others' skills, gave rise to the more theatrical lam glawn, traditionally given as a night-long performance at temple fairs, in which male and female singers perform passages of poetry interspersed with improvised repartee to the accompaniment of the khene. Complementing the lam and khap of the Lao ethnic majority, several Tay-Tai speaking ethnic minority peoples preserve their own call-and-response dialog song traditions in which boys and girls engage in flirtatious vocal banter.

There are important differences between lam and its northern counterpart, khap. Repartee between couples is an important feature of all varieties of khap, but it can be distinguished from lam by its additional use of a chorus to repeat phrases uttered by the male and female soloists. In Luang Prabang, both khap thum and khap salang samsao utilize a small orchestra made up of classical instruments drawn from the court piphat tradition.

Theater

Ancient traditions such as lam contributed to the later development of other performing arts. During the latter half of the nineteenth century, as the growing urbanization of Southeast Asia gave rise to new popular musical theatre genres, a theatrical derivative of lam pheun, known as lam luang, emerged in Laos. Lam luang, a combination of singing and storytelling with improvisation, acting and dance, performed to a musical accompaniment, is thought to have originated when the moh lam (lam singer) began to act out all the parts in his story, changing his costume and movement with each character. Under the influence of Siamese likay, Cambodian yike and Vietnamese cải lương, lam luang came to involve as many as 30 performers acting out the various roles. From an early date musical accompaniment included both traditional Lao and western instruments. In 1972, the Pathet Lao established the Central Lao Opera (Lam Luang) Troupe in the north of the country to promote lam luang as a national popular art form. Though no longer popular in the cities, lam luang has retained its appeal in rural areas of Laos and is frequently used as a means of educating the public about social issues such AIDS, drug awareness, and health.

The oldest extant form of Lao puppetry, or lakhon tukkata, is found in Luang Prabang, where a troupe based at Wat Xieng Thong preserves the ipok rod-puppet tradition associated with the former royal court. The Ipok Puppet Troupe of Luang Prabang performs with the original puppets carved for King Sakkarin (1895-1904) in the Siamese hun style; held from below on sticks, with jointed arms manipulated by strings, they are used to recount stories from the Lao Ramayana and from local traditions. The repertoire focuses on three Lao traditional stories, Karaket, Sithong Manora and Linthong. Each show is preceded by a ceremony to honor the spirits of the ancestors embodied in the puppets, which are stored at the wat when not in use. Unfortunately the puppeteers are now very old and the provincial government is urgently seeking outside assistance to preserve this dying art form.

Khene

The unique and haunting drone of the Lao national instrument, the khene, is an essential component of the folk music of Laos. The khene (also spelled "khaen," "kaen" and "khen"; Lao: ແຄນ, Thai: แคน) is a mouth organ of Lao origin whose seven or sometimes eight pairs of bamboo and reed pipes are fitted into a small, hollowed-out hardwood reservoir into which air is blown. The moh khene (khene player) blows into the soundbox and pitch is determined by means of holes bored into the tubes which, when blocked, bring into action vibrating reeds of silver fitted into each tube. Similar instruments date back to the Bronze Age of Southeast Asia.

The most interesting characteristic of the khene is its free reed, which is made of brass or silver. The khene uses a pentatonic scale in one of two modes (thang sun and thang yao), each mode having three possible keys. The khene has five different lai, or modes: Lai yai, lai noi, lai sootsanaen, lai po sai, and lai soi. Lai po sai is considered to be the oldest of the lai khene, and lai sootsanaen is called the "Father of the Lai Khene." The khene has seven tones per octave, with intervals similar to that of the Western diatonic natural A-minor scale: A, B, C, D, E, F, and G. A khene can be made in a particular key but can not be tuned after the reed is set and the pipes are cut. If the khaen is played along with other instruments the others have to tune to the khene. The khene can be played as a solo instrument (dio khaen), as part of an ensemble (ponglang), or as an accompaniment to a Lao or Isan Folk Opera Singer mor lam.

Lao Music in Thailand

Following the Siamese conquest of Laos in 1828, and the subsequent dispersion of the Lao population into Siam (Central Thailand), Lao music became fashionable there. Sir John Bowring, an envoy from Great Britain, described a meeting with the deputy king (ouparaja) of Siam in 1855 in which his host performed on the Lao khene; at a meeting two days later he entertained Bowring with Lao dancers and khene music. The Chronicles of the Fourth Reign said the deputy king enjoyed playing the khene and "could perform the Lao type of dance and could skillfully perform the Lao comedy-singing. It is said that if one did not actually see his royal person, one would have thought the singer were a real Lao."

Immediately after the deputy king's death in 1865, King Mongkut made known his fear that Lao musical culture would supplant Siamese genres and banned Lao musical performances in a proclamation in which he complained that, "Both men and women now play Lao khene (mo lam) throughout the kingdom… Lao khene is always played for the topknot cutting ceremony and for ordinations. We cannot give the priority to Lao entertainments. Thai have been performing Lao khene for more than ten years now and it has become very common. It is apparent that wherever there is an increase in the playing of Lao khene there is also less rain."

In recent years Lao popular music has made inroads into Thailand through the success of contemporary Lao musicians Alexandria, L.O.G., and Cells.

Contemporary music in Laos

Contemporary mor lam is very different from that of previous generations. Instead of traditional genres, singers perform three-minute songs combining lam segments with pop style sections, while comedians perform skits in between blocks of songs.[14] In recent decades there has been a growing tendency, particularly in the south of the country, to use modern Western instruments in accompaniment of lam.

A blend of lam and Western pop music known as lam luang samay, performed to the accompaniment of a khene backed up by a modern band of electric guitar, bass, keyboard and drums has become popular at outdoor events. Lam luang samay takes as its theme both traditional and contemporary stories. Traditionally, the tune was developed by the singer as an interpretation of glawn poems and accompanied primarily by the khene, but the modern form is most often composed and uses electrified instruments. Contemporary forms of the music are characterized by a quick tempo and rapid delivery, strong rhythmic accompaniment, vocal leaps, and a conversational style of singing that can be compared to American rap.

Rock bands popular with the younger generation in Laos include The Cell, Smile Black Dog, Dao Kha Chai, Awake, Khem Tid, Eighteen and Black Burn, Aluna, Overdance and LOG. Lao music today exhibits a wide variety of styles and different national origins. Outside of Laos, Lao music is mainly created in the United States, France and Canada. An increasing amount of transnational Lao (alternative) rock, pop and hip has given rise to a new genre alongside traditional Lao music such as morlam.

See also

Notes

- ↑ Visiting Arts, Buddhist Sculpture, Laos Cultural Profile. Retrieved October 6, 2008.

- ↑ Visiting Arts, Buddhist Painting, Laos Cultural Profile. Retrieved October 6, 2008.

- ↑ UNESCO, Phase I: Pilot project in Luang Prabang. Retrieved October 6, 2008.

- ↑ An Excavation at the Sisattanak Kiln Site, Vientiane, Lao P.D.R., 1989, 1992).

- ↑ Visiting Arts, Ethnic minority architecture, Laos Cultural Profile. Retrieved October 6, 2008.

- ↑ Visiting Arts, Modern and contemporary art, Laos Cultural Profile. Retrieved October 6, 2008.

- ↑ Visiting Arts, Buddhist Painting, Laos Cultural Profile. Retrieved October 6, 2008.

- ↑ The Music of Southeast Asia: Laos, The traditional music of Laos, An Overview. Retrieved October 6, 2008.

- ↑ Visiting Arts, Lakhon pharak pharam—Lao classical music and dance, Laos Cultural Profile. Retrieved October 6, 2008.

- ↑ Visiting Arts, Ethnic minority performing arts, Laos Cultural Profile. Retrieved October 6, 2008.

- ↑ Visiting Arts, Fon phun muang - Lao folk dance, Laos Cultural Profile. Retrieved October 6, 2008.

- ↑ Terry E. Miller, Traditional Music of the Lao, 295.

- ↑ Terry Miller (ed.), Garland Encyclopedia of World Music: Volume 4, 325.

- ↑ Creedopedia, Mor Lam.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Giteau, Madeleine. Art et archéologie du Laos. Picard, 2001. ISBN-13 978-2708405868.

- Gosling, Betty. Old Luang Prabang. Images of Asia. New York: Oxford University Press, 1996. ISBN 9835600066.

- Lonely Planet. Laos: Arts. Retrieved October 6, 2008.

- Marchal, Henri. L’Art decoratif au Laos; Arts Asiatiques 10 (2) 1964.

- Miller, Terry E. An Introduction to Playing the Kaen. Kent, OH: T.E. Miller, 1980.

- Miller, Terry E. Traditional Music of the Lao: Kaen Playing and Mawlum Singing in Northeast Thailand. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1985. ISBN 0-313-24765-X.

- Nanongkham, Priwan. Khaen Repertories: The Developments of Lao Traditional Music in Northeast Thailand. Retrieved October 6, 2008.

- Somkiart Lopetcharat: Lao Buddha—The Image and Its History. Art Media Resources Ltd., 2001. ISBN 9789742722074.

External links

All links retrieved October 22, 2022.

- Khaen

- The traditional music of Laos

- Traditional Music and & Songs Archive Traditional Music and Songs in Laos

- Khaen World Instrument Gallery

- Collection III: The Voice of the Khen (Khaen) Traditional Music and Songs in Laos

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

- Lao_Buddhist_sculpture history

- Lao_ceramics history

- Lao_music history

- Khene history

- Luang_Prabang history

- Marc_Leguay history

- Pak_Ou_Caves history

- Culture_of_Laos history

- Mor_lam history

- Glawn history

- Emerald_Buddha history

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.