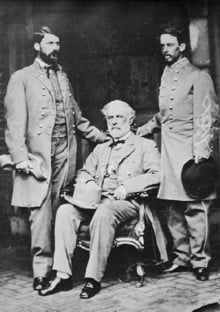

Robert Edward Lee (January 19, 1807 â October 12, 1870) was a career army officer and the most successful general of the Confederate forces during the American Civil War. He eventually commanded all Confederate armies as general-in-chief. Like Hannibal earlier and Rommel later, his victories against superior forces in an ultimately losing cause won him enduring fame. After the war, he urged sectional reconciliation, and spent his final years as a devoted college president. Lee remains an iconic figure of the Confederacy in the Southern states to this day. During his own lifetime, he was respected by his enemies and can perhaps be regarded as the right man on the wrong side of a war that not only almost divided a nation but that was, in part, a struggle to abolish slavery and towards the realization of the high ideals expressed in the founding documents of the United States. Even though this ideal is still elusive, those who won the war he so nobly lost were representatives of democracy and freedom.

Early life and career

Robert Edward Lee was born at Stratford Hall Plantation, in Westmoreland County, Virginia, the fourth child of American Revolutionary War hero Henry Lee ("Lighthorse Harry") and Anne Hill (née Carter) Lee. He entered the United States Military Academy in 1825. When he graduated (second in his class of 46) in 1829 he had not only attained the top academic record but was the first cadet (and so far the only) to graduate the Academy without a single demerit. He was commissioned as a second lieutenant in the Army Corps of Engineers.

Lee served for seventeen months at Fort Pulaski on Cockspur Island, Georgia. In 1831, he was transferred to Fort Monroe, Virginia, as assistant engineer. While he was stationed there, he married Mary Anna Randolph Custis (1808â1873), the great-granddaughter of Martha Washington (George Washington's wife), at Arlington House, her parents' home just across from Washington, D.C. They eventually had seven children, three boys and four girls: George Washington Custis Custis, William Henry Fitzhugh Lee, Robert Edward, Mary, Annie, Agnes, and Mildred.

Engineering

Lee served as an assistant in the chief engineer's office in Washington from 1834 to 1837, but spent the summer of 1835 helping to lay out the state line between Ohio and Michigan. In 1837, he got his first important command. As a first lieutenant of engineers, he supervised the engineering work for St. Louis harbor and for the upper Mississippi and Missouri rivers. His work there earned him a promotion to captain. In 1841, he was transferred to Fort Hamilton in New York Harbor, where he took charge of building fortifications.

Mexican War, West Point, and Texas

Lee distinguished himself in the Mexican War (1846â1848). He was one of Winfield Scott's chief aides in the march from Veracruz to Mexico City. He was instrumental in several American victories through his personal reconnaissance as a staff officer; he found routes of attack that the Mexicans had not defended because they thought the terrain was impassable.

He was promoted to major after the Battle of Cerro Gordo in April 1847. He also fought at Contreras and Chapultepec, and was wounded at the latter. By the end of the war he had been promoted to lieutenant colonel.

After the Mexican War, he spent three years at Fort Carroll in Baltimore harbor, after which he became the superintendent of West Point in 1852. During his three years at West Point, he improved the buildings, the courses, and spent a lot of time with the cadets. Lee's oldest son, George Washington Custis Lee, attended West Point during his tenure. Custis Lee graduated in 1854, first in his class.

In 1855, Lee became Lieutenant Colonel of the Second Cavalry and was sent to the Texas frontier. There he helped protect settlers from attacks by the Apache and the Comanche.

These were not happy years for Lee as he did not like to be away from his family for long periods of time, especially as his wife was becoming increasingly ill. Lee returned home to see her as often as he could.

He happened to be in Washington at the time of abolitionist John Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry, Virginia (now West Virginia) in 1859, and was sent there to arrest Brown and to restore order. He did this very quickly and then returned to his regiment in Texas. When Texas seceded from the Union in 1861, Lee was called to Washington, D.C. to wait for further orders.

Lee as slave owner

As a member of the Virginia aristocracy, Lee had lived in close contact with slavery all of his life, but he never held more than about a half-dozen slaves under his own nameâin fact, it was not positively known that he had held any slaves at all under his own name until the rediscovery of his 1846 will in the records of Rockbridge County, Virginia, which referred to an enslaved woman named Nancy and her children, and provided for their manumission in case of his death.[1]

However, when Lee's father-in-law, George Washington Parke Custis, died in October 1857, Lee came into a considerable amount of property through his wife, and also gained temporary control of a large population of slavesâsixty-three men, women, and children, in allâas the executor of Custis's will. Under the terms of the will, the slaves were to be freed "in such manner as to my executors may seem most expedient and proper," with a maximum of five years from the date of Custis's death provided to arrange for the necessary legal details of manumission.[2]

Custis's will was probated on December 7, 1857. Although Robert Lee Randolph, Right Reverend William Meade, and George Washington Peter were named as executors along with Robert E. Lee, the other three men failed to qualify, leaving Lee with the sole responsibility of settling the estate, and with exclusive control over all of Custis's former slaves. Although the will provided for the slaves to be emancipated "in such a manner as to my executors may seem most expedient and proper," Lee found himself in need of funds to pay his father-in-law's debts and repair the properties he had inherited; he decided to make money during the five years that the will had allowed him control of the slaves by hiring them out to neighboring plantations and to eastern Virginia (where there were more jobs to be found). The decision caused dissatisfaction among Custis's slaves, who had been given to understand that they were to be made free as soon as Custis died.

In 1859, three of the slavesâWesley Norris, his sister Mary, and a cousin of theirsâfled for the North. Two 1859 anonymous letters to the New York Tribune (dated June 19[3] and June 21[4]), based on hearsay and an 1866 interview with Wesley Norris,[5] printed in the National Anti-Slavery Standard record that the Norrises were captured a few miles from the Pennsylvania border and returned to Lee, who had them whipped and their lacerated backs rubbed with brine. After the whipping, Lee forced them to go to work in Richmond, Virginia, and then Alabama, where Wesley Norris gained his freedom in January 1863 by escaping through the rebel lines to Union-controlled territory.

Lee released Custis's other slaves after the end of the five-year period in the winter of 1862.

Lee's views on slavery

Since the end of the Civil War, it has often been suggested that Lee was in some sense opposed to slavery. In the period following the Civil War and Reconstruction, Lee became a central figure in the lost cause of the Confederacy interpretation of the war, and as succeeding generations came to look on slavery as a terrible wrong, the idea that Lee had always somehow opposed it helped maintain his stature as a symbol of Southern United States honor and national reconciliation.

The most common lines of evidence cited in favor of the claim that Lee opposed slavery are: (1) the manumission of Custis's slaves, as discussed above; (2) Lee's 1856 letter to his wife in which he states that "There are few, I believe, in this enlightened age, who will not acknowledge that slavery as an institution is a moral and political evil,"[6] and (3) his support, towards the very end of the Civil War, for enrolling slaves in the Confederate army, with manumission as an eventual reward for good service.

Critics object that these interpretations mischaracterize Lee's actual statements and actions to imply that he opposed slavery. The manumission of Custis's slaves, for example, is often mischaracterized as Lee's own decision, rather than a requirement of Custis's will. Similarly, Lee's letter to his wife is being misrepresented by selective quotation; while Lee does describe slavery as an evil, he immediately goes on to write:

It is useless to expatiate on its disadvantages. I think it however a greater evil to the white man than to the black race, and while my feelings are strongly enlisted in behalf of the latter, my sympathies are more strong for the former. The blacks are immeasurably better off here than in Africa, morally, socially and physically. The painful discipline they are undergoing, is necessary for their instruction as a race, and I hope will prepare and lead them to better things. How long their subjugation may be necessary is known and ordered by a wise Merciful Providence.[6]

In fact, the main topic of the letterâa comment in approval of a speech by President Franklin Pierceâis not the evils of slavery at all, but rather a condemnation of abolitionism, which Lee describes as "irresponsible and unaccountable" and an "evil Course."

Finally, critics charge that whatever private reservations Lee may have held about slavery, he participated fully in the slave system, and does not appear to have publicly challenged it in any way until the partial and conditional plan, under increasingly desperate military circumstances, to arm slaves.

Civil War

On April 18, 1861, on the eve of the American Civil War, President Abraham Lincoln, through Secretary of War Simon Cameron, offered Lee command of the United States Army (Union Army) through an intermediary, Maryland Republican politician Francis P. Blair, at the home of Blair's son Montgomery Blair, Lincoln's Postmaster-General, in Washington. Lee's sentiments were against secession, which he denounced in an 1861 letter as "nothing but revolution" and a betrayal of the efforts of the Founders. However his loyalty to his native Virginia led him to join the Confederacy.

At the outbreak of war he was appointed to command all of Virginia's forces, and then as one of the first five full generals of Confederate forces. Lee, however, refused to wear the insignia of a Confederate general stating that, in honor to his rank of Colonel in the United States Army, he would only display the three stars of a Confederate colonel until the Civil War had been won and Lee could be promoted, in peacetime, to a general in the Confederate Army.

After commanding Confederate forces in western Virginia, and then in charge of coastal defenses along the Carolina seaboards, he became military adviser to Jefferson Davis, president of the Confederate States of America, whom he knew from West Point.

Commander, Army of Northern Virginia

Following the wounding of Gen. Joseph E. Johnston at the Battle of Seven Pines, on June 1, 1862, Lee assumed command of the Army of Northern Virginia, his first opportunity to lead an army in the field. He soon launched a series of attacks, the Seven Days Battles, against General George B. McClellan's Union forces threatening Richmond, Virginia, the Confederate capital. Lee's attacks resulted in heavy Confederate casualties and they were marred by clumsy tactical performances by his subordinates, but his aggressive actions unnerved McClellan. After McClellan's retreat, Lee defeated another Union army at the Second Battle of Bull Run. He then invaded Maryland, hoping to replenish his supplies and possibly influence the Northern elections that fall in favor of ending the war. McClellan obtained a lost order that revealed Lee's plans and brought superior forces to bear at Battle of Antietam before Lee's army could be assembled. In the bloodiest day of the war, Lee withstood the Union assaults, but withdrew his battered army back to Virginia.

Disappointed by McClellan's failure to destroy Lee's army, Lincoln named Ambrose Burnside as commander of the Army of the Potomac. Burnside ordered an attack across the Rappahannock River at Battle of Fredericksburg. Delays in getting pontoon bridges built across the river allowed Lee's army ample time to organize strong defenses, and the attack on December 12, 1862, was a disaster for the Union. Lincoln then named Joseph Hooker commander of the Army of the Potomac. Hooker's advance to attack Lee in May 1863, near Battle of Chancellorsville, Virginia, was defeated by Lee and Thomas J. Jackson's daring plan to divide the army and attack Hooker's flank. It was an enormous victory over a larger force, but came at a great cost as Jackson, Lee's best subordinate, was mortally wounded.

In the summer of 1863, Lee proceeded to invade the North again, hoping for a Southern victory that would compel the North to grant Confederate independence. But his attempts to defeat the Union forces under George G. Meade at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, failed. His subordinates did not attack with the aggressive drive Lee expected, J.E.B. Stuart's cavalry was out of the area, and Lee's decision to launch a massive frontal assault on the center of the Union lineâthe disastrous Pickett's Chargeâresulted in heavy losses. Lee was compelled to retreat again but, as after Antietam, was not vigorously pursued. Following his defeat at Gettysburg, Lee sent a letter of resignation to Confederate President Jefferson Davis on August 8, 1863, but Davis refused Lee's request.

In 1864, the new Union general-in-chief Ulysses S. Grant sought to destroy Lee's army and capture Richmond. Lee and his men stopped each advance, but Grant had superior reinforcements and kept pushing each time a bit further to the southeast. These battles in the Overland Campaign included the Battle of the Wilderness, Battle of Spotsylvania Court House, and Battle of Cold Harbor. Grant eventually fooled Lee by stealthily moving his army across the James River (Virginia). After stopping a Union attempt to capture Petersburg, Virginia, a vital railroad link supplying Richmond, Lee's men built elaborate trenches and were besieged in Petersburg. He attempted to break the stalemate by sending Jubal A. Early on a raid through the Shenandoah Valley to Washington, D.C., but Early was defeated by the superior forces of Philip Sheridan. The Siege of Petersburg would last from June 1864 until April 1865.

General-in-chief

On January 31, 1865, Lee was promoted to general-in-chief of Confederate forces. In early 1865, he urged adoption of a scheme to allow slaves to join the Confederate army in exchange for their freedom. The scheme never came to fruition in the short time the Confederacy had left before it ceased to exist.

As the Confederate army was worn down by months of battle, a Union attempt to capture Petersburg, Virginia on April 2, 1865, succeeded. Lee abandoned the defense of Richmond and sought to join General Joseph Johnston's army in North Carolina. His forces were surrounded by the Union army and he surrendered to General Grant on April 9, 1865, at Appomattox Court House, Virginia. Lee resisted calls by some subordinates (and indirectly by Jefferson Davis) to reject surrender and allow small units to melt away into the mountains, setting up a lengthy guerrilla war.

After the war

Following the war, Lee applied for, but was never granted, the official postwar amnesty. After filling out the application form, it was delivered to the desk of Secretary of State William H. Seward, who, assuming that the matter had been dealt with by someone else and that this was just a personal copy, filed it away until it was found decades later in his desk drawer. Lee took the lack of response either way to mean that the government wished to retain the right to prosecute him in the future.

Lee's example of applying for amnesty was an encouragement to many other former members of the Confederate States of America's armed forces to accept being citizens of the United States once again. In 1975, President Gerald Ford granted a posthumous pardon and the U.S. Congress restored his citizenship, following the discovery of his oath of allegiance by an employee of the National Archives and Records Administration in 1970.

Lee and his wife had lived at his wife's family home prior to the Civil War, the Custis-Lee Mansion. It was confiscated by Union forces, and is today part of Arlington National Cemetery. After his death, the courts ruled that the estate had been illegally seized, and that it should be returned to Lee's son. The government offered to buy the land outright, to which he agreed.

He served as president of Washington College (now Washington and Lee University) in Lexington, Virginia, from October 2, 1865, until his death in 1870. Over five years he transformed Washington College from a small, undistinguished school into one of the first American colleges to offer courses in business, journalism, and Spanish language. He also imposed a sweeping and breathtakingly simple concept of honorâ"We have but one rule, and it is that every student is a gentleman"âthat endures today at Washington and Lee and at a few other schools that continue to maintain absolutist "honor systems." Importantly, Lee focused the college on attracting as students men from the North as well as the South. The college remained racially segregated, however; after John Chavis, admitted in 1795, Washington and Lee did not admit a second black student until 1966.

Final illness and death

On the evening of September 28, 1870, Lee fell ill, unable to speak coherently. When his doctors were called, the most they could do was help put him to bed and hope for the best. It is almost certain that Lee had suffered a stroke. The stroke damaged the frontal lobes of the brain, which made speech impossible, and made him unable to cough. He was force-fed to keep up his strength, but he developed pneumonia. With no ability to cough, Lee died from the effects of pneumonia (not from the stroke itself). He died two weeks after the stroke on the morning of October 12, 1870, in Lexington, Virginia, and was buried underneath the chapel at Washington and Lee University.

Quotes

- "There are few, I believe, in this enlightened age, who will not acknowledge that slavery as an institution is a moral and political evil. It is idle to expatiate on its disadvantages. I think it is a greater evil to the white than to the colored race. The blacks are immeasurably better off here than in Africa, morally, physically, and socially. The painful discipline they are undergoing is necessary for their further instruction as a race, and will prepare them, I hope, for better things. How long their servitude may be necessary is known and ordered by a merciful Providence. Their emancipation will result from the mild and melting influences of Christianity than from the storm and tempest of fiery controversy." Lee's response to a speech given by President Franklin Pierce, December 1856.

- "It is well that war is so terrible. We should grow too fond of it." Lee's remark made at the battle of Fredericksburg, December 1862.

- "After four years of arduous service, marked by unsurpassed courage and fortitude, the Army of Northern Virginia has been compelled to yield to overwhelming numbers and resources.

I need not tell you the brave survivors of so many hard fought battles who have remained steadfast to the last, that I have consented to this result from no distrust of them, but feeling that valor and devotion could accomplish nothing that could compensate for the loss that would have attended the continuance of the contest, I determined to avoid the useless sacrifice of those whose past services have endeared them to their countrymen. By the terms of the agreement, Officers and men can return to their homes and remain until exchanged. You will take with you the satisfaction that proceeds from the consciousness of duty faithfully performed and I earnestly pray that a merciful God will extend to you His blessing and protection. With an unceasing admiration of your constancy and devotion to your country, and a grateful remembrance of your kind and generous consideration of myself, I bid you all an affectionate farewell." General Order Number 9 upon the surrender to Union General U.S. Grant, April, 1865.

Monuments and memorial

Lee County, Alabama is named in his honor. Arlington House, also known as the Custis-Lee Mansion and located in present-day Arlington National Cemetery, is maintained by the National Park Service as a memorial to the family.

Legacy

Few men who lost a war retain as high a reputation on both sides as did General Lee. Those against whom he fought respected him, even though they wished he was not their enemy. In war, he was a brilliant strategist and biographer Al Kaltman (2000) comments that his tactics are still studied today.[7] Kaltman suggests that Lee himself had little concern for his legacy but wanted to get on with the job in hand. He also suggests that Lee was an excellent manager and that valuable advice can be extrapolated from Lee's example, including that managers should set an example just as parents should for their children, that they should âavoid making remarks and taking actions that foster petty jealousies and unprofessional attitudes and conductâ[8] and even that in the company of women men should refrain from âsexual innuendoâ which disrupts the workplace.[9] Lee stressed rising to a challenge, working with available resources (he fought a wealthier and better equipped enemy), striving for continual improvement and projecting a confident image in the face of adversity. In peace, Lee tried to reconcile former enemies and to âbind the nation's wounds.â[10] While loyalty to his state divided him from the Union, his instincts were sympathetic towards the one-nation understanding of statehood. His views on slavery were ambivalent and again he lent towards abolition rather than retention.

In his study of Lee, Brian Reid remarks that a process of hero-making has surrounded Lee's legacy, especially in the South.[11] As the vanquished hero, Lee can be represented sentimentally as a character whose deeds and values all but prove that the wrong side won. However, he also suggests that Lee's military brilliance requires no vindication or embellishment, although some have it that he was too defensive as a tactician and that eventually he defeated himself. Reid says that Lee's best qualities were his imagination, decisiveness, stamina, and the determination to win the Civil War rather than lose it.

Notes

- â George Washington Parke Custis' Will ChickenBones: A Journal.

- â Will of George Washington Parke Custis ChickenBones: A Journal.

- â Letter from "A Citizen" (1859) New York Daily Tribune, June 24, 1859. Retrieved December 6, 2012.

- â "Some Facts that Should Come to Light" (1859) New York Daily Tribune, June 24, 1859. Retrieved December 6, 2012.

- â Testimony of Wesley Norris (1866) National Anti-Slavery Standard, April 14, 1866. Retrieved December 6, 2012.

- â 6.0 6.1 Letter to his wife on slavery (selections; December 27, 1856) Retrieved December 6, 2012.

- â Al Kaltman, The Genius of Robert E Lee (Paramus, NJ: Prentice Hall, 2000, ISBN 0735201870).

- â Kaltman 2000, 23.

- â Kaltman 2000, 18.

- â Kaltman 2000, 340.

- â Brian Holden Reid, Robert Lee: Icon for a Nation (New York, NY: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 2005, ISBN 029784699X).

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Kaltman, Al. The Genius of Robert E Lee. Paramus, NJ: Prentice Hall, 2000. ISBN 0735201870

- Reid, Brian Holden. Robert Lee: Icon for a Nation. New York, NY: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 2005. ISBN 029784699X

External links

All links retrieved December 15, 2022.

- R. E. Lee, the biography by Douglas Southall Freeman (4 vols., complete online version)

- Robert E. Lee Historical Preservation Site

- Lee Chapel at Washington and Lee University where Robert E. Lee is buried

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.