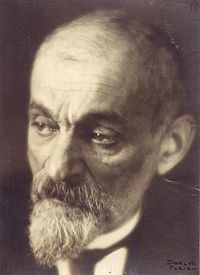

Lev Shestov

| Western Philosophy 19th-century philosophy | |

|---|---|

| |

| Name: Lev Shestov | |

| Birth: January 31, 1866 (Kiev, Russian Empire) | |

| Death: November 19, 1938 (Paris, France) | |

| School/tradition: Irrationalism, Existentialism | |

| Main interests | |

| Theology, Nihilism | |

| Notable ideas | |

| {{{notable_ideas}}} | |

| Influences | Influenced |

| Friedrich Nietzsche, Soren Kierkegaard, Dostoevsky, Leo Tolstoy | D. H. Lawrence, Nikolai Berdyaev, Sergei Bulgakov, Albert Camus, John Middleton Murry, Jules de Gaultier, Lucien Lйvy-Bruhl |

Lev Isaakovich Shestov (Russian: Лев Исаакович Шестов), born Yehuda Leyb Schwarzmann (Russian: Иегуда Лейб Шварцман)) was a Russian—Jewish existentialist writer and philosopher. He was the first Russian philosopher to find an audience in Europe. Shestov was an irrationalist whose philosophy ran counter to the prevailing rationalism of his day. Shestov rejected any rational basis for God. He abhored the rational religion of Western philosophy (for example, Immanuel Kant's Religion within the Limits of Reason Alone), arguing that God is beyond rational comprehension and even morality. Shestov's ideas were certainly influenced by his exposure to the Russian Orthodox Church. His insistence on the absoluteness and incomprehensibility of God through reason were a response to the rationalism of Western philosophy and ideology.

He emigrated to France in 1921, fleeing from the aftermath of the October Revolution. He lived in Paris until his death on November 19, 1938.

Life

Shestov was born Lev Issakovich Schwarzmann on January 31 (February 13), 1866, in Kiev into a Jewish family. He obtained an education at various places, due to fractious clashes with authority. He went on to study law and mathematics at Moscow State University but after a clash with the Inspector of Students he was told to return to Kiev, where he completed his studies.

Shestov's dissertation prevented him from becoming a doctor of law, as it was dismissed on account of its revolutionary tendencies. In 1898, he entered a circle of prominent Russian intellectuals and artists which included Nikolai Berdyaev, Sergei Diaghilev, Dmitri Merezhkovsky, and Vasily Rozanov. Shestov contributed articles to a journal the circle had established. During this time he completed his first major philosophical work, Good in the teaching of Tolstoy and Nietzsche: Philosophy and Preaching; two authors that had a profound impact on Shestov's thinking.

He further developed his thinking in a second book on Dostoevsky and Nietzsche, which increased Shestov's reputation as an original and incisive thinker. In All Things Are Possible (published in 1905), Shestov adopted the aphoristic style of Friedrich Nietzsche. Shestov dealt with such issues as religion, rationalism, and science in this brief work, issues he would examine in later writings.

However, Shestov's works were not met with approval, even by some of his closest Russian friends. Many saw in Shestov's work, a renunciation of reason and metaphysics, and even an espousal of nihilism. Nevertheless, he would find admirers in such writers as D.H. Lawrence.

In 1908, Shestov moved to Freiburg, Germany, and he stayed there until 1910, when he moved to the small Swiss village of Coppet. During this time the author worked prolifically. One of the fruits of these labors was the publication of Great Vigils and Penultimate Words. He returned to Moscow in 1915, and in this year his son Sergei died in combat against the Germans. During the Moscow period, his work became more influenced by matters of religion and theology. The seizure of government by the Bolsheviks in 1919 made life difficult for Shestov, and the Marxists pressured him to write a defense of Marxist doctrine as an introduction to his new work, Potestas Clavium; otherwise it would not be published. Shestov refused this, yet with the permission of the authorities he lectured at the University of Kiev on Greek philosophy.

Shestov's dislike of the Soviet regime led him to undertake a long journey out of Russia, and he eventually ended up in France. The author was a popular figure in France, where his originality was quickly recognized. That this Russian was newly appreciated is attested by his having been asked to contribute to a prestigious French philosophy journal. In the interwar years, Shestov continued to develop into a thinker of great prominence. During this time he had become totally immersed in the study of such great theologians such as Blaise Pascal and Plotinus, while at the same time lecturing at the Sorbonne in 1925. In 1926, he was introduced to Edmund Husserl, with whom he maintained a cordial relationship despite radical differences in philosophical outlook. In 1929, during a return to Freiburg he met with Martin Heidegger, and was urged to study Danish philosopher Søren Kierkegaard.

The discovery of Kierkegaard prompted Shestov to realize that his philosophy shared great similarities, such as his rejection of idealism, and his belief that man can gain ultimate knowledge through ungrounded subjective thought rather than objective reason and verifiability. However, Shestov maintained that Kierkegaard did not pursue this line of thought far enough, and proceeded to continue where he thought the Dane left off. The results of this tendency are seen in his work Kierkegaard and Existential Philosophy: Vox Clamantis in Deserto, published in 1936, a fundamental work of religious existentialism.

Despite his weakening condition Shestov continued to write at a quick pace, and finally completed his magnum opus, Athens and Jerusalem. This work examines the necessity that reason be rejected in the discipline of philosophy. Furthermore, it adumbrates the means by which the scientific method has made philosophy and science irreconcilable, since science concerns itself with empirical observation, whereas (so Shestov argues) philosophy must be concerned with freedom, God, and immortality, issues that cannot be solved by science.

In 1938, Shestov contracted a serious illness while at his vacation home. During this final period, he continued his studies, concentrating in particular on Indian Philosophy as well as the works of his contemporary Edmund Husserl, who had died recently. Shestov himself died at a clinic in Paris.

Philosophy

The Philosophy of Despair

Shestov's philosophy owes a great debt to that of Friedrich Nietzsche both in style and substance. Like Nietzsche, Shestov's philosophy is, at first sight, not a philosophy at all: it offers no systematic unity, no coherent set of propositions, no theoretical explanation of philosophical problems. Most of Shestov's work is fragmentary. With regard to the form (he often used aphorisms) the style may be deemed more web-like than linear, and more explosive than argumentative. The author seems to contradict himself on every page, and even seeks out paradoxes. This is because he believes that life itself is, in the last analysis, deeply paradoxical, and not comprehensible through logical or rational inquiry. Shestov maintains that no theory can solve the mysteries of life. Fundamentally, his philosophy is not "problem-solving," but problem-generating, with a pronounced emphasis on life's enigmatic qualities.

His point of departure is not a theory, or an idea, but an experience. Indeed, it is the very experience described so eloquently by nineteenth century British poet, James Thomson, in his pessimistic expression of urban life in the Industrial Revolution, The City of Dreadful Night:

- The sense that every struggle brings defeat

- Because Fate holds no prize to crown success;

- That all the oracles are dumb or cheat

- Because they have no secret to express;

- That none can pierce the vast black veil uncertain

- Because there is no light beyond the curtain;

- That all is vanity and nothingness.

It is the experience of despair, which Shestov describes as the loss of certainties, the loss of freedom, the loss of the meaning of life. The root of this despair is what he frequently calls "Necessity," but also "Reason," "Idealism," or "Fate": a certain way of thinking (but at the same time also a very real aspect of the world) that subordinates life to ideas, abstractions, generalizations and thereby kills it, through an ignoring of the uniqueness and "livingness" of reality.

"Reason" is the obedience to and the acceptance of Certainties that tell us that certain things are eternal and unchangeable and other things are impossible and can never be attained. This accounts for the view that Shetov's philosophy is a form of irrationalism, though it is important to note that the thinker does not oppose reason, or science in general, but only rationalism and scientism: the tendency to consider reason as a sort of omniscient, omnipotent God that is good for its own sake. It may also be considered a form of personalism: people cannot be reduced to ideas, social structures, or mystical oneness. Shestov rejects any mention of "omnitudes," "collective," "all-unity." As he explains in his masterpiece Athens and Jerusalem:

"But why attribute to God, the God whom neither time nor space limits, the same respect and love for order? Why forever speak of "total unity"? If God loves men, what need has He to subordinate men to His divine will and to deprive them of their own will, the most precious of the things He has bestowed upon them? There is no need at all. Consequently the idea of total unity is an absolutely false idea....It is not forbidden for reason to speak of unity and even of unities, but it must renounce total unity—and other things besides. And what a sigh of relief men will breathe when they suddenly discover that the living God, the true God, in no way resembles Him whom reason has shown them until now!"

Through this attack on the "Self evident," Shestov implies that we are all seemingly alone with our suffering, and can be helped neither by others, nor by philosophy. This explains his lack of a systematic philosophical framework.

Penultimate Words: Surrender versus Struggle

But despair is not the last word, it is only the "penultimate word." The last word can't be said in human language, can't be captured in theory. His philosophy begins with despair, his whole thinking is desperate, but Shestov tries to point to something beyond despair—and beyond philosophy.

This is what he calls "faith": not a belief, not a certainty, but another way of thinking that arises in the midst of the deepest doubt and insecurity. It is the experience that everything is possible (Dostoevsky), that the opposite of Necessity is not chance or accident, but possibility, that there does exist a God-given freedom without boundaries, without walls or borders. Shestov maintains that we should continue to struggle, to fight against Fate and Necessity, even when a successful outcome is not guaranteed. Exactly at the moment that all the oracles remain silent, we should give ourselves over to god, who alone can comfort the sick and suffering soul. In some of his most famous words he explains:

"Faith, only the faith that looks to the Creator and that He inspires, radiates from itself the supreme and decisive truths condemning what is and what is not. Reality is transfigured. The heavens glorify the Lord. The prophets and apostles cry in ecstasy, "O death, where is thy sting? Hell, where is thy victory?" And all announce: "Eye hath not seen, non ear heard, neither have entered into the heart of man, the things which God hath prepared for them that love Him."

Furthermore, although acknowledged as a Jewish philosopher, Shestov saw in the resurrection of Christ this victory over necessity. He courageously proclaimed the incarnation and resurrection to be a transfiguring spectacle in which god was showing humanity that the purpose of life is indeed not "mystical" surrender to the "absolute," but ascetical struggle:

"Cur Deus homo? Why, to what purpose, did He become man, expose himself to injurious mistreatment, ignominious and painful death on the cross? Was it not in order to show man, through His example, that no decision is too hard, that it is worth while bearing anything in order not to remain in the womb of the One? That any torture whatever to the living being is better than the 'bliss' of the rest-satiate 'ideal' being?"

Likewise, the final words of his last and greatest work, Athens and Jerusalem, end: "Philosophy is not Besinnen [surrender] but struggle. And this struggle has no end and will have no end. The kingdom of God, as it is written, is attained through violence."

Legacy

Shestov was highly admired and honored by Nikolai Berdyaev and Sergei Bulgakov in Russia, Jules de Gaultier, Lucien Levy-Brühl and Albert Camus in France, and D.H. Lawrence and John Middleton Murry in England.

Shestov isn't very well-known, even in the academic world. This is partly due to the fact that his works weren't readily available for a long time (which has changed with The Lev Shestov), partly also to the specific themes he discusses (unfashionable and "foreign" to the English-speaking world) and partly the consequence of the sombre and yet ecstatic atmosphere that permeates his writings—his quasi-nihilistic position and his religious outlook which make for an unsettling and incongruous combination to contemporary Western readers.

He did however influence writers like Albert Camus (who wrote about him in Le Mythe de Sisyphe), Benjamin Fondane (his "pupil"), and notably Emil Cioran, who writes about Shestov: "He was the philosopher of my generation, which didn't succeed in realizing itself spiritually, but remained nostalgic about such a realization. Shestov [...] has played an important role in my life. [...] He thought rightly that the true problems escape the philosophers. What else do they do but obscuring the real torments of life?"[1] Shestov also appears in the work of Gilles Deleuze.

More recently, alongside Dostoevsky's philosophy, many have found solace in Shestovs battle against the rational self-consistent and self-evident; for example Bernard Martin of Columbia University, who translated his works now found online; and the scholar, who wrote "The Annihilation of Inertia: Dostoevsky and Metaphysics." This book was an evaluation of Dostoyevsky's struggle against the self-evident "wall," and refers to Shestov on several occasions.

Main Works

These are Shestovs most important works, in their English translations, and with their date of writing:

- The Good in the Teaching of Tolstoy and Nietzsche, 1899

- The Philosophy of Tragedy, Dostoevsky and Nietzsche, 1903

- All Things are Possible (Apotheosis of Groundlessness), 1905

- Potestas Clavium, 1919

- In Job's Balances, 1923-1929

- Kierkegaard and the Existential Philosophy, 1933-1934

- Athens and Jerusalem, 1930-1937

Notes

- ↑ Emil Cioran, Oeuvres, Paris: Gallimard, 1995

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Martin, Bernard. 1966. Lev Shestov - Introduction. Ohio University Press. Retrieved January 2, 2006.

- Strelsky, Nikander. 1980 "Lev Shestov," in Columbia Dictionary of Modern European Literature. Columbia University Press. ISBN 9780231037174

- Terras, Victor. 1991. A History of Russian Literature. Yale University Press. ISBN 0300059345

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.