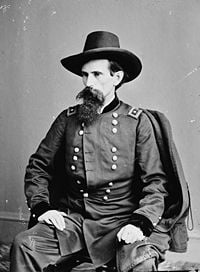

Lew Wallace

| Lew Wallace | |

|---|---|

| April 10, 1827 – February 15, 1905 | |

Lew Wallace | |

| Place of birth | Brookville, Indiana |

| Place of death | Crawfordsville, Indiana |

| Allegiance | United States |

| Years of service | 1846 – 1847; 1861 – 1865 |

| Rank | Major General |

| Commands held | 11th Indiana Infantry 3rd Division, Army of the Tennessee |

| Battles/wars | American Civil War

|

| Other work | Author of Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ, territorial governor of New Mexico, U.S. minister to Turkey |

Lewis "Lew" Wallace (April 10, 1827 – February 15, 1905) was a self taught lawyer, governor, Union general in the American Civil War, American statesman, and author, best remembered for his historical novel Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ.

Early life

Wallace was born in Brookville, Indiana, to a prominent local family. His father, David Wallace, served as Indiana Governor; his mother, Zerelda Gray Sanders Wallace, was a prominent temperance and suffragist activist. He briefly attended Wabash College in Crawfordsville, Indiana. He started working in the county clerks office and studied his father's law books in his spare time. He served in the Mexican War as a first lieutenant with the First Indiana Infantry regiment. After the war, he returned to Indianapolis and was admitted to the bar in 1849. He began practicing law and served two terms as prosecuting attorney of Covington, Indiana. In 1853, he moved to Crawfordsville and was elected to the Indiana Senate in 1856. In 1852, he married Susan Arnold Elston by whom he had one son.

Civil War

At the start of the Civil War, Wallace was appointed state adjutant general and helped raise troops in Indiana. On April 25, 1861, he was appointed Colonel of the Eleventh Indiana Infantry. After brief service in western Virginia, he was promoted to brigadier general of volunteers on September 3 1861. In February 1862, he was a division commander fighting under Brig. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant at the Battle of Fort Donelson. During the fierce Confederate assault on February 15, 1862 Wallace coolly acted on his own initiative to send a brigade to reinforce the beleaguered division of Brigadier John A. McClernand, despite orders from Grant to avoid a general engagement. This action was key in stabilizing the Union defensive line. Wallace was promoted to major general in March.

Shiloh

Wallace's most controversial command came at the Battle of Shiloh, where he continued as a division commander under Grant. Wallace's division had been left as reserves at a place called Stoney Lonesome to the rear of the Union line. Early in the morning, when Grant's army was surprised and virtually routed by the sudden appearance of the Confederate States Army under Albert Sidney Johnston, Grant sent orders for Wallace to move his unit up to support the division of William Tecumseh Sherman.

Wallace claimed that Grant's orders were unsigned, hastily written, and overly vague. There were two paths by which Wallace could move his unit to the front, and Grant (according to Wallace) did not specify which route he was directed. Wallace chose to take the upper path, which was less used and in considerably better condition, and which would lead him to the right side of Sherman's last known position. Grant later claimed that he had specified that Wallace take the lower path, though circumstantial evidence seems to suggest that Grant had forgotten that more than one path even existed.

Wallace arrived at the end of his march only to find that Sherman had been forced back, and was no longer where Wallace thought he would be found. Moreover, he had been pushed back so far that Wallace now found himself in the rear of the advancing Southern troops. Nevertheless, a messenger from Grant arrived with word that Grant was wondering where Wallace was, and why he had not arrived at Pittsburg Landing, where the Union was making its stand. Wallace was confused. He felt sure he could viably launch an attack from where he was and hit the Rebels in the rear. He decided to turn his troops around and march back to Stoney Lonesome. For some reason, rather than realigning his troops so that the rear guard would be in the front, Wallace chose to countermarch his column; he argued that his artillery would have been greatly out of position to support the infantry when it would arrive on the field.

Wallace marched back to Stoney Lonesome, and arrived at 11:00 a.m. It had now taken him five hours of marching to return to where he started, with somewhat less rested troops. He then proceeded to march over the lower road to Pittsburg Landing, but the road had been left in terrible conditions by recent rainstorms and previous Union marches, so the going was extremely slow. Wallace finally arrived at Grant's position at about 7:00 p.m., at a time when the fighting was practically over. However, the Union came back to win the battle the following day.

There was little fallout from this initially as Wallace was the youngest general of his rank in the army, and was something of a "golden boy." Civilians in the North began to hear the news of the horrible casualties at Shiloh, and the Army needed explanations. Both Grant and his superior, Maj. Gen. Henry Wager Halleck, placed the blame squarely on Wallace, saying that his incompetence in moving up the reserves had nearly cost them the battle. Sherman, for his part, remained mute on the issue. Wallace was removed from his command in June, and reassigned to the much less glamorous duty commanding the defenses of Cincinnati in the Department of the Ohio.

Later service

In July 1864, Wallace produced mixed results in the Battle of Monocacy Junction, part of the Valley Campaigns of 1864: his army (the Middle Department) was defeated by Confederate General Jubal A. Early, but was able to delay Early's advance toward Washington, D.C., sufficiently that the city defenses had time to organize and repel Early.

General Grant's memoirs assessed Wallace's delaying tactics at Monocacy:

If Early had been but one day earlier, he might have entered the capital before the arrival of the reinforcements I had sent. ...General Wallace contributed on this occasion by the defeat of the troops under him, a greater benefit to the cause than often falls to the lot of a commander of an equal force to render by means of a victory.

Personally, Wallace was devastated by the loss of his reputation as a result of Shiloh. He worked desperately all his life to change public opinion about his role in the battle, going so far as to literally beg Grant to "set things right" in Grant's memoirs. Grant, however, like many of the others refused to change his opinion.

Postwar career

Wallace participated in the military commission trial of the Lincoln assassination conspirators as well as the court-martial of Henry Wirz, commandant of the Andersonville prison camp. He resigned from the army in November 1865. Late in the war, he directed secret efforts by the government to help the Mexicans remove the French occupation forces who had seized control of Mexico in 1864. He continued in those efforts more publicly after the war and was offered a major general's commission in the Mexican army after his resignation from the U.S. Army. Multiple promises by the Mexican revolutionaries were never delivered, which forced Wallace into deep financial debt.

Wallace held a number of important political posts during the 1870s and 1880s. He served as governor of New Mexico Territory from 1878 to 1881, and as U.S. Minister to the Ottoman Empire from 1881 to 1885. As governor he offered amnesty to many men involved in the Lincoln County War; in the process he met with Billy the Kid (William Bonney). Billy the Kid met with Wallace, and the pair arranged that Kid would act as an informant and testify against others involved in the Lincoln County War, and, in return, Kid would be "scot free with a pardon in [his] pocket for all [his] misdeeds." But the Kid returned to his outlaw ways and Governor Wallace withdrew his offer. While serving as governor, Wallace completed the novel that made him famous: Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ (1880). It grew to be the best selling American novel of the nineteenth century. The book has never been out of print and has been filmed four times.

Recently, historian Victor Davis Hanson has argued that the novel was based heavily on Wallace's own life, particularly his experiences at Shiloh and the damage it did to his reputation. There are some striking similarities: the book's main character, Judah Ben-Hur accidentally causes injury to a high-ranking commander, for which he and his family suffer no end of tribulations and calumny. Ben-Hur was the first work of fiction to be blessed by a pope.

Wallace died from cancer in Crawfordsville, Indiana, and is buried there in Oak Hill Cemetery. A marble statue of him dressed in a military uniform by sculptor Andrew O'Connor was placed in the National Statuary Hall Collection by the state of Indiana in 1910 and is currently located in the west side of the National Statuary Hall.

Religious Views

Wallace wrote his best selling Ben Hur to defend belief in God against the criticisms of Robert G. Ingersoll (1833-1899). Sub-titled 'A Tale of Christ' the novel is actually the story of a Jewish aristocrat who, condemned to slavery, becomes a Roman citizen and a champion charioteer and seeks revenge against his former Roman friend who has condemned him as a rebel. References to Jesus are woven into the narrative. Wallace depicted Jesus as a compassionate, healing, faith-inspiring teacher but also as transcending racial, cultural and religious divides. Wallace's Jesus is for all the world. Ben Hur at first thought that Jesus intended to overthrow the yoke of Rome but then realized that his was a spiritual message that was also addressed to Romans. In his Prince of India (1893), Wallace speaks about "Universal Religion" and about all religions finding their fulfilment in Jesus, to whom "all manking are brethren" (Volume I: 286). Wallace became a "believer in God and Christ" while writing Ben Hur (1906: 937).

Religions, he wrote, might retain their titles but war between them would cease. He suggested that religious traditions themselves become the subject of worship, instead of God (ibid: 60). He seems to have regarded Jesus as a teacher of eternal wisdom in whom people from any faith can find inspiration and meaning. "Heaven may be won," say the three Magi in Ben Hur, 'not by sword, not by human wisdom, but by Faith, Love and Good Works'. Wallace would have been aware of the meeting of religious leaders that took place in Chicago in 1893, the Parliament of the World's Religions and appears to have shared the idea that all religions share basic values in common.

Another interesting apect of his writing is the very positive and muscular portrait of Ben Hur, who is vey different from the "Jew as victim" stereotype of much Christian literature. Ben Hur is a hero who overcomes adversity to triumph against his enemies and who remains proud of his Jewish identity throughout the novel. This resonated with the concept of Jews as makers of their own destiny of the emerging Zionist movement. Wallaces respectful treatment of the Jewish identity of both Jesus and of his hero, Ben Hur, anticipated a later tendency in Biblical scholarship to locate Jesus within his Jewish context instead of seeing him as alien to that context. While writing Ben Hur, too, he spent hours studying maps of the Holy Land, so that his references would be geographically accurate. Most sholars at the time saw the task of reconstructing the life of Jesus as one of textual interpretation. Wallace went beyond the text and, again anticipating later trends, wanted to penetrate the mind of Jesus. Visiting the Holy Land from Turkey, he wrote that he was gratified to find "no reason for making a single change in the text" of Ben Hur (1906: 937). Visiting the Holy Land would also become de rigeur for Bible scholars and Jesus' biographers.

Works

- The Fair God; or, The Last of the 'Tzins: A Tale of the Conquest of Mexico (Boston: James R. Osgood and Company), 1873.

- Commodus: An Historical Play ([Crawfordsville, IN?]: privately published by the author), 1876. (revised and reissued again in the same year)

- Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ (New York: Harper & Brothers), 1880.

- The Boyhood of Christ (New York: Harper & Brothers), 1888.

- Life of Gen. Ben Harrison (bound with Life of Hon. Levi P. Morton, by George Alfred Townsend), (Cleveland: N. G. Hamilton & Co., Publishers), 1888.

- Life of Gen. Ben Harrison (Philadelphia: Hubbard Brothers, Publishers), 1888.

- Life and Public Serives of Hon. Benjmain Harrison, President of the U.S. With a Concise Biographical Sketch of Hon. Whitelaw Reid, Ex-Minister to France [by Murat Halstad] (Philadelphia: Edgewood Publishing Co.), 1892.

- The Prince of India; or, Why Constantinople Fell (New York: Harper & Brothers Publishers), 1893. 2 volumes

- The Wooing of Malkatoon [and] Commodus (New York: Harper and Brothers Publishers), 1898.

- Lew Wallace: An Autobiography (New York: Harper & Brothers Publishers), 1906. 2 volumes

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Compilation of Works of Art and Other Objects in the United States Capitol. Architect of the Capitol under the Joint Committee on the Library. United States Government Printing House, Washington, 1965.

- Eicher, John H., and David J. Eicher. Civil War High Commands, Stanford University Press, 2001. ISBN 0804736413.

- Grant, Ulysses S. Personal Memoirs of U. S. Grant. Charles L. Webster & Company, 1886. ISBN 0914427679.

- Hanson, Victor Davis. Ripples of Battle: How Wars of the Past Still Determine How We Fight, How We Live, and How We Think. Doubleday, 2003. ISBN 0385504004.

- Warner, Ezra J. Generals in Blue: Lives of the Union Commanders. Louisiana State University Press, 1964. ISBN 0807108227.

External links

All links retrieved March 11, 2025.

- "General Lew Wallace Study & Museum" – City of Crawfordsville

- "Lew Wallace, 1827-1905" – Gutenburg.org.

- "Wallace" – The Political Graveyard.

- "Meet Lew Wallace: Timeline of an American Hero" – General Lew Wallace Museum.

| Preceded by: Samuel Beach Axtell |

Governor of New Mexico 1878-1881 |

Succeeded by: Lionel Allen Sheldon |

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.