Li Tieguai

Li Tieguai (śĚéťďĀśčź: meaning "Iron-crutch Li" ) (Wade-Giles: "Li T'ieh-kuai" ) is one of the most ancient of the Eight Immortals of the Daoist pantheon. Given the wide discrepancies in the dates ascribed to his mortal life (from the Tang ,618-906 C.E.,[1] to the Yuan, 1279-1368 C.E.,[2] dynasties), it seems reasonable to assume that he is a legendary (rather than historical) figure.[3]

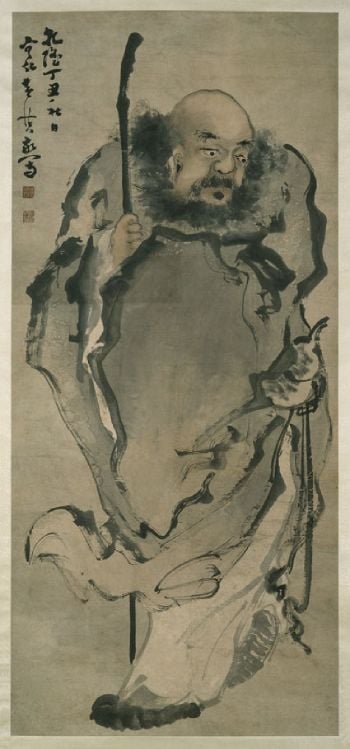

In Chinese art, Li Tieguai is portrayed as an ugly old beggar with a dirty face and unkempt beard, walking with the aid of a large iron crutch. He is described as irascible and ill-tempered, but also benevolent to the poor, sick, and the needy, whose suffering he alleviates with medicine from his gourd bottle.

Member of the Eight Immortals

Li Tieguai is one of the illustrious Eight Immortals (Ba Xian), a group of Daoist/folk deities who play an important role in Chinese religion and culture. While they are famed for espousing and teaching Daoist philosophy and cultivation practices, they are also figures of popular myth and legend that are known for their devotion to the downtrodden and their collective lifestyle of ‚Äúfree and easy wandering.‚ÄĚ Though they are most often depicted and described in the context of their group, each has their own particular set of tales, iconography, and areas of patronage.

Legends

The character of Li Tieguai stands at the center of a considerable complex of legends and myths. One such story says that when he was younger, Li Tieguai was a handsome and motivated man who achieved fame for his ascetic and philosophical acumen. By his early thirties, he was able to go for weeks without eating or drinking, and could become so attuned to the Dao that he was like a dead man. Word of these exploits eventually reached the divinized Laozi, who allegedly returned to earth to become Li's patron and mentor. (In some versions, he is instead instructed by the Queen Mother of the West.)[4]

Under Laozi's expert tutelage, Li's aptitude at various magical and superhuman feats flourished, eventually earning him a following of devoted pupils and admirers. Eventually, Laozi taught Li how to make a voyage of the spirit‚ÄĒseparating his soul from his body in order to travel to the celestial realms. After this final lesson, the Old Master invited his pupil to visit him in the heavenly abode of the immortals and gods.

Duly excited by this possibility, Li Tieguai began to prepare for his journey, instructing his most prized student in how to care for his material body while he was away. As a contingency, he further advised the young man that his body should be immediately cremated if he did not return within seven days. Unfortunately, while Li Tieguai's spirit was off among the celestial spheres, his pupil received some troubling news: His beloved mother had taken ill. Though he was consumed by anxiety over his mother's health, the young apprentice remained conscious of his duty to his master and continued his vigil over Li's lifeless body. However, on the evening of the sixth day, this stress proved to be too taxing. The student, sure that his master had forever departed the material realm, quickly burned his body and rushed home to tend to his mother. Soon after, Li's soul returned to our plane, only to find that his fine-featured body had been reduced to a pile of ashes. Fearful that he should be extinguished, Li quickly entered the first available material form that he could find‚ÄĒthe body of a recently expired beggar-man.

At first, Li Tieguai's vanity railed against this repulsive form (as the beggar was covered in sores, had enormous bulging eyes, and smelled incredibly foul) and he considered leaving it in search of a preferable body. To his surprise, Laozi suddenly appeared and suggested that accepting this body might be the final step he would require to truly embrace immortality. No sooner had these words been spoken than Li realized the irrelevance of the form of his material body. In honor of his student's revelation, Laozi gave him two gifts: An unbreakable staff (which the beggar needed to walk around) and a gourd filled with a magical elixir that could cure all illnesses. With that, Laozi instructed his newly-immortal pupil to act for the good of all people and vanished. Li Tieguai's first act after this revelation was to visit his neglectful student's home and to cure his ailing mother. After this point, he became a wandering healer who constantly looked out for the needs of the downtrodden.[5]

Following his assumption into the ranks of the immortals, Li Tieguai remained an active participant in the lives of everyday people. Some of these adventures include ministering to the sick and pronouncing moral sanctions against immoral magistrates,[6] rewarding honest and hard-working peasants and fisherman,[7] exposing the evils of corruption in the imperial bureaucracy,[8] and teaching the worthy about the secrets of immortality.[9]

In some ways, Li Tieguai can be seen to represent an archetypal Daoist hero. Not only does he possess the supernatural efficacy (De) necessary to permit miraculous intercession in worldly affairs, but he achieved this skill through a process of gradual cultivation (using philosophical, meditational, alchemical, and dietary methods).[10] Indeed, "he was so saturated with the Taoist contempt of the vanitas vanitatum and the ambitions of the world, that he determined to lead a life of asceticism."[11] Further, he represents an additional Daoist archetype by virtue of his physical hideousness. The manner in which Li Tieguai's frightening exterior conceals a generous and spiritually potent soul is a perfect illustration of the Zhuangzi's contention that human categories (such as beautiful/ugly) are both arbitrary and contingent. Indeed, strong parallels can be seen between the bug-eyed, repulsive beggar that is Li Tieguai and Zhuangzi's motley assortment of physically awkward teachers and exemplars (a group that includes Crippled Shu, Clubfoot Hunchback No-Lips, Jug-Jar Big-Goiter, Shu-Shan No-Toes).[12] However, in his desire to aid all people (especially the needy and oppressed), Li Tieguai also possesses the characteristics of a potent folk deity, which is likely why he became a figure of veneration.

Iconographic representation

In pictorial representations, Li Tieguai is portrayed as a physically repugnant beggar, often with protruding eyes, a balding pate, and ragged clothing. Because of his lame and twisted legs, he is always depicted holding himself up using a large metal crutch. Finally, images of Li usually feature a gourd bottle, which he wears slung over one shoulder. This bottle is understood to contain the mysterious medicine gifted to him by Laozi.[13]

Area of patronage

First and foremost, Li Tieguai is seen as the patron of doctors and pharmacists, likely due to his reputation as a healer.[14] Due to this connection, the signs at traditional Chinese dispensaries often bear the image of his crutch or gourd.[15] Likewise, his spiritual potency has made him a favorite among some religious Daoists and spirit mediums.[16] Finally, he is seen as the patron of cripples, beggars, and other social undesirables.[17]

Notes

- ‚ÜĎ Wong, 27.

- ‚ÜĎ Werner, 345.

- ‚ÜĎ Pas, 202.

- ‚ÜĎ Werner, 343.

- ‚ÜĎ Werner, 343-344.

- ‚ÜĎ Ho and O'Brien, 109-112.

- ‚ÜĎ Ho and O'Brien, 105-108.

- ‚ÜĎ Ho and O'Brien, 100-104.

- ‚ÜĎ Ling, 62.

- ‚ÜĎ Ling, 61-62.

- ‚ÜĎ Ling, 61.

- ‚ÜĎ Watson, 62.

- ‚ÜĎ Ling, 61-62; Goodrich, 313-314.

- ‚ÜĎ Pas, 202.

- ‚ÜĎ Werner, 141; Ho and O'Brien, 26.

- ‚ÜĎ Ho and O'Brien, 26.

- ‚ÜĎ Goodrich, 313-314.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Fowler, Jeaneane. An Introduction to the Philosophy and Religion of Taoism. Portland, OR: Sussex Academic Press, 2005. ISBN 1-84519-085-8

- Goodrich, Anne S. Peking Paper Gods: A Look at Home Worship. Nettetal: Steyler-Verlag, 1991. ISBN 3-8050-0284-X

- Ho, Kwok Man and Joanne O'Brien, trans and eds. The Eight Immortals of Taoism. New York: Meridian, 1990. ISBN 0-452-01070-5

- Kohn, Livia. Daoism and Chinese Culture. Cambridge, MA: Three Pines Press, 2001. ISBN 1-931483-00-0

- Ling, Peter C. "The Eight Immortals of the Taoist Religion." Journal of the North China Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society XLIX (1918). 58-75.

- Pas, Julian F. and Man Kam Leung. ‚ÄúLi T‚Äôieh-Kuai/Li Tieguai.‚ÄĚ Historical Dictionary of Taoism. London: The Scarecrow Press, 1998. ISBN 0-8108-3369-7

- Schipper, Kristofer. The Taoist Body. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1993. ISBN 0-520-05488-1

- Watson, Burton, trans. Chuang Tzu: Basic Writings. New York: Columbia University Press, 1996. ISBN 0-231-10595-9

- Werner, E.T.C. "Pa-Hsien." In A Dictionary of Chinese Mythology. Wakefield, NH: Longwood Academic, 1990. ISBN 0-89341-034-9

- Wong, Eva. Tales of the Taoist Immortals. Boston: Shambala, 2001. ISBN 1-57062-809-2

- Yetts, W. Perceval. "The Eight Immortals." Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Britain and Ireland for 1916 (1916). 773-806.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.