Lollardy

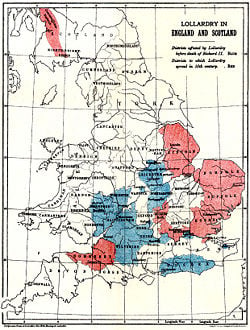

Lollardy or Lollardry was the political and religious movement of the Lollards from the late fourteenth century to early in the time of the English Reformation. Lollardy followed from the teachings of John Wyclif, a prominent theologian at the University of Oxford beginning in the 1350s. Its demands were primarily for reform of the Roman Catholic Church.

It taught that piety was a requirement for a priest to be a "true" priest or to perform the sacraments, and that a pious layman had power to perform those same rites, believing that religious power and authority came through piety and not through the Church hierarchy. Similarly, Lollardy also emphasized the authority of the Scriptures over the authority of priests. It taught the concept of the "Church of the Saved", meaning that Christ's true Church was the community of the faithful, which overlapped with but was not the same as the official Church of Rome. It taught a form of predestination. It advocated apostolic poverty and taxation of Church properties. It also denied transubstantiation in favor of consubstantiation. Through its influence on Jan Hus, it had a wide impact on the pre-reformation reformist movements. Especially following the Peasants' Revolt (1381) Lollardy was widely perceived to threaten State as well as Church authority, since it encouraged all people to access God directly through the scriptures.

Etymology

Lollard, Lollardi, or Loller was the popular derogatory nickname given to those without an academic background, educated if at all only in English, who were reputed to follow the teachings of John Wycliffe in particular, and were certainly considerably energised by the translation of the Bible into the English. The alternative, Wycliffite, is generally accepted to be a more neutral term covering those of similar opinions, but having an academic background.

The origin of the term is clouded with uncertainty, but four possibilities suggest themselves:

- The Dutch word, lollaerd, meaning someone who mutters, a mumbler. This is also related to the Dutch word, lull or lollen, as in "a mother lulls her child to sleep", or "to sing or chant";

- The Latin lolium, tares (mingled with the Catholic wheat);

- after the Franciscan, Lolhard, who converted to the Waldensian way, becoming eminent as a preacher in Guienne. That part of France was then under English domination, influencing lay English piety. He was burned at Cologne in the 1370s;

- The Middle-English loller, "a lazy vagabond, an idler, a fraudulent beggar", likely a later usage; influenced by Chaucer's use of the term in the Canterbury Tales.

- The Dutch derivation is the most likely, due to the influence on Lollardy of the informal lay communities, originating in Deventer in Overijssel around the teaching of Gerhard Groote, in the last two decades of the fourteenth century; but the Latin lolium (tares) an interesting alternative, supported by Chaucer's Epilogue to the Man of Law's Tale, in his description of the Poor Parson's preaching:

"And he'll go starting up some heresy

And sow his tares in our clean corn, perchance."

Perhaps we do not have to make a choice, for all were contemptuous marks of abuse, initially roundly detested by those to whom attached; but worn with pride by later Lollards.

Beliefs

Although Lollardy can be said to have originated in the writings of John Wyclif, it is true that the Lollards had no central doctrine. Likewise, being a decentralized movement, Lollardy neither had nor proposed any singular authority. The movement associated itself with many different ideas, but individual Lollards did not necessarily have to agree with every tenet.

Fundamentally, Lollards were anticlerical. They believed the Roman Catholic Church to be corrupt in many ways and looked to Scripture as the basis for their religion. To provide an authority for religion outside of the Church, Lollards began the movement towards a translation of the bible into the vernacular; Wyclif himself in his works translated many passages.

One group of Lollards petitioned parliament with The Twelve Conclusions of the Lollards. While by no means a central authority of the Lollards, the Twelve Conclusions reveal certain basic Lollard ideas. The Lollards stated that the Catholic Church had been corrupted by temporal matters and that its claim to be the true church was not justified by its heredity. Part of this corruption involved prayers for the dead and chantries. These were seen as corrupt since they distracted priests from other work and that all should be prayed for equally. Lollards also had a tendency to iconoclasm. Lavish church fixtures were seen as an excess; they believed effort should be placed on helping the needy and preaching rather than working on lavish decoration. Icons were also seen as dangerous since many seemed to worship the icon rather than God, leading to idolatry.

Believing in a lay priesthood, the Lollards challenged the Church’s ability to invest or deny the divine authority to make a man a priest. Denying any special authority to the priesthood, Lollards thought confession unnecessary since a priest did not have any special power to forgive sins. Lollards challenged the practice of clerical celibacy and believed priests should not hold political positions since temporal matters should not interfere with the priests’ spiritual mission.

Believing that more attention should be given to the message in the scriptures rather than to ceremony and worship, the Lollards denounced the ritualistic aspects of the Church such as transubstantiation, exorcism, pilgrimages, and blessings. These focused too much on powers the Church supposedly did not have and led to a focus on temporal ritual over God and his message.

The Twelve Conclusions also denounce war and violence, even capital punishment. Abortion is also denounced.

Outside of the Twelve Conclusions, the Lollards had many beliefs and traditions. Their scriptural focus led Lollards to refuse the taking of oaths. Lollards also had a tradition of millenarianism. Some criticized the Church for not focusing enough on Revelation. Many Lollards believed they were near the end of days, and several Lollard writings claim the Pope to be the antichrist.

History

Immediately upon going public, Lollardy was attacked as heresy. At first, Wyclif and Lollardy were protected by John of Gaunt and anti-clerical nobility, who were most likely interested in using Lollard-advocated clerical reform to create a new source of revenue from England’s monasteries. The University of Oxford also protected Wyclif and allowed him to hold his position at the university in spite of his views on the grounds of academic freedom, which also gave some protection to the academics who supported it within that institution. Lollardy first faced serious persecution after the Peasants' Revolt in 1381. While Wyclif and other Lollards opposed the revolt, one of the peasants’ leaders, John Ball, preached Lollardy. The royalty and nobility then found Lollardy to be a threat not just to the Church, but to all the English social order. The Lollards' small measure of protection evaporated. This change in status was also affected by the removal of John of Gaunt from the scene, when he left England in pursuit of the throne of Castile, which he claimed through his second wife.

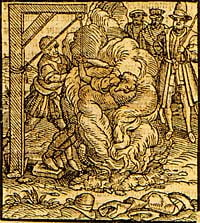

Lollardy was strongly resisted by both the religious and secular authorities. Among those opposing it was Thomas Arundel, Archbishop of Canterbury. King Henry IV passed the De heretico comburendo in 1401, not specifically agaist the Lollards, but prohibiting the translating or owning of the Bible and authorising the burning of heretics at the stake.

In the early fifteenth century, Lollardy went underground after more extreme measures were taken by the Church and State. The one of these measures was the burning at the stake of John Badby, a layman and artisan who refused to renounce his Lollard views. His was the first execution of a layman in England for the crime of heresy. A group of Lollard knights had been a powerful force in English politics, but even these powerful noblemen did not escape this crackdown. Sir John Oldcastle, a close friend of King Henry V was brought to trial in 1413 after evidence of his Lollard beliefs was uncovered. Oldcastle escaped from the Tower of London and organized an insurrection, which included an attempted kidnapping of the king. The rebellion failed, and Oldcastle was executed. Oldcastle's revolt made Lollardy seem even more threatening to the state, and the persecution of Lollards became more severe. A variety of other martyrs for the Lollard cause were executed over the following century, including Thomas Harding who died at White Hill, Chesham, in 1532, one of the last Lollards to be persecuted.

Lollards were effectively absorbed into Protestantism during the English Reformation, in which Lollardy played a role. Since Lollardy had been underground for more than 100 years, the extent of Lollardy and its ideas at the time of the Reformation is uncertain and a point of debate. However, many critics of the Reformation, including Thomas More, associated Protestants with Lollards. Protestant leaders, including Archbishop Cranmer, referred to Lollardy as well. Whether Protestants actually drew influence from Lollardy or whether they referred to it to create a sense of tradition is debated by scholars. The extent of Lollardy in the general populace at this time is also unknown, but the prevalence of Protestant iconoclasm in England suggests Lollard ideas may still have had some popular influence if Zwingli was not the source, as Lutherans did not advocate iconoclasm. The similarity between Lollards and later English Protestant groups such as the Baptists, Puritans and Quakers also suggests some continuation of Lollard ideas through the Reformation. John Knox, the leader of the Reformation in Scotland, may have been unable to graduate from St Andrews because he refused to sign a repudiation of Lollardy. Jan Hus drew much of his inspiration from Lollardy.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Hudson, Anne. The Premature Reformation: Wycliffite Texts and Lollard History. New York: Oxford University Press, 2002. ISBN 9780198227625

- Rex, Richard. The Lollards (Social History in Perspective). New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2002. ISBN 9780333597521

- Wicliffe, John, and James Henthron Todd (ed.). An Apology For Lollard Doctrines, Attributed To Wicliffe. Whitefish, MT: Kessinger Publishing, LLC, 2007 ISBN 9781430452126

External links

All links retrieved November 3, 2022.

- The Lollard Society - society dedicated to providing a forum for the study of the Lollards.

- Lollards in the Catholic Encyclopedia - Lollardy as a heresy, from the Roman Catholic perspective.

- Lollards - essay on Lollards on Medieval Church website, including extensive list of secondary sources.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.