Mahajanapadas

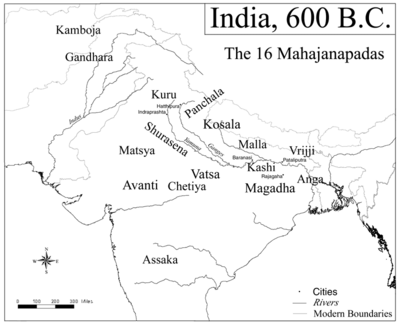

Mahajanapadas (Sanskrit: महाजनपद, Mahājanapadas) literally "Great Kingdoms" (from Maha, "great," and Janapada "foothold of a tribe," "country") refers to 16 monarchies and 'republics' that stretched across the Indo-Gangetic plains from modern-day Afghanistan to Bangladesh in the sixth century B.C.E., prior to and during the rise of Buddhism in India. They represent a transition from a semi-nomadic tribal society to an agrarian-based society with a vast network of trade and a highly-organized political structure. Many of these “kingdoms” functioned as republics governed by a general assembly and a council of elders led by an elected “king consul.” The Mahajanapadas are the historical context of the Sanskrit epics, such as the Mahabharata and the Ramayana as well as Puranic literature (the itihasa). They were also the political and social context in which Buddhism and Jainism emerged and developed.

Most of the historical details about the Mahajanapadas are culled from Sanskrit literature. Buddhist and Jaina texts refer to the Mahajanapadas only incidentally. In a struggle for supremacy during the fifth century B.C.E., the growing state of Magadha emerged as the most predominant power in ancient India, annexing several of the Janapadas. They were all eventually absorbed into the the Maurya Empire after 321 B.C.E.

Origins

The political structure of the ancient Indians appears to have started with semi-nomadic tribal units called Jana (meaning subjects). Early Vedic texts speak of several Janas, or tribes, of Aryans, organized as semi-nomadic tribal states, fighting among themselves and with other non-Aryan tribes for cattle, sheep and green pastures. These early Vedic Janas later coalesced into the Janapadas of the Epic Age.

The term "Janapada" literally means the foothold of a tribe. The fact that Janapada is derived from Jana suggests the taking of land by a Jana tribe for a settled way of life. This process of settlement on land had completed its final stage prior to the times of Buddha and Panini. The Pre-Buddhist north-west region of the Indian sub-continent was divided into several Janapadas demarcated from each other by boundaries. In the Panini grammar, Janapada stands for country and Janapadin for its citizenry. Each Janapada was named after the Kshatriya tribe (or Kshatriya Jana) who had settled there[1] [2][3][4] [5].

Tribal identity was more significant than geographical location in defining the territory of a Janapada, and the sparsity of the population made specific boundary lines unimportant. Often rivers formed the boundaries of two neighboring kingdoms, as was the case between the northern and southern Panchala and between the western (Pandava's Kingdom) and eastern (Kaurava's Kingdom) Kuru. Sometimes, large forests, which were larger than the kingdoms themselves, formed boundaries, such as the Naimisha Forest between Panchala and Kosala kingdoms. Mountain ranges like Himalaya, Vindhya and Sahya also formed boundaries.

Economic and political organization

The development of a stable agricultural society led to concepts of private property and land revenue, and to new forms of political and economic organization. Commerce among the Janapadas expanded through the Ganges Valley, and powerful urban trading centers emerged. Craftsmen and traders established guilds (shrem) and a system of banking and lending, issuing script and minting coins, of which the earliest were silver-bent bars and silver and copper punch-marked coins.

Many Janapadas were republics (ghana-sangas), either single tribes or a confederacy of tribes, governed by a general assembly (parishad) and a council of elders representing powerful kshatriya families (clans). One of the elders was elected as a chief (raja or pan) or "king consul," to preside over the assembly. Monarchies came to embody the concept of hereditary ascension to the throne and the association of the king with a divine status, accompanied by elaborate ceremonies and sacrifices.

Some kingdoms possessed a main city that served as a capital, where the palace of the ruler was situated. In each village and town, taxes were collected by the officers appointed by the ruler in return for protection from the attacks of other rulers and robber tribes, as well as from invading foreign nomadic tribes. The ruler also enforced law and order in his kingdom by punishing the guilty.

The republics provided a climate in which unorthodox views were tolerated, and new schools of thought such as Buddhism and Jainism emerged and spread. These challenged the orthodox Vedic social order and the exclusivity of the caste system, emphasizing equality and a rational approach to social relations. This approach appealed to the wealthy as well as the poor because it allowed for social mobility, and royal patronage supported missionaries who spread Buddhism over India and abroad. By the third century B.C.E. Jainism had already reached many parts of India.

The Mahajanapadas of the late Vedic (from about 700 B.C.E.) are the historical context of the Sanskrit epics, such as the Mahabharata and the Ramayana as well as Puranic literature (the itihasa). Most of the historical details about the Mahajanapadas are culled from this literature. Buddhist and Jaina texts refer to the Mahajanapadas only casually and give no historical details about them.

Disappearance

In a struggle for supremacy that followed in the sixth/fifth century B.C.E., the growing state of Magadha emerged as the most predominant power in ancient India, annexing several of the Janapadas of the Majjhimadesa. A bitter line in the Brahmin Puranas laments that Magadhan emperor Mahapadma Nanda exterminated all Kshatriyas, none worthy of the name Kshatrya being left thereafter. This obviously refers to the Kasis, Kosalas, Kurus, Panchalas, Vatsyas and other neo-Vedic tribes of the east Panjab of whom nothing was ever heard except in the legend and poetry.

According to Buddhist texts, the first 14 of the Mahajanapadas belong to Majjhimadesa (Mid India) while the Kambojans and Gandharans belong to Uttarapatha or the north-west division of Jambudvipa. These last two never came into direct contact with the Magadhan state until the rise of the Maurya Empire in 321 B.C.E. They remained relatively isolated but were invaded by the Achaemenids of Persia during the reign of Cyrus (558-530 B.C.E.) or in the first year of Darius. Kamboja and Gandhara formed the twentieth and richest strapy of Achaemenid Empire. Cyrus I is said to have destroyed the famous Kamboja city called Kapisi (modern Begram) in Paropamisade (Paropamisus Greek for Hindu Kush). In 327 B.C.E. the Greeks under Alexander of Macedon overran the Punjab, but withdrew after two years, creating an opportunity for Chandragupta Maurya to step in.

Mahajanapadas

Buddhist and other texts make incidental references to 16 great nations (Solasa Mahajanapadas) which were in existence before the time of Buddha, but do not give any connected history except in the case of Magadha. In several passages, the ancient Buddhist text Anguttara Nikaya[6], gives a list of 16 great nations:

Another Buddhist text written in Pali, Digha Nikaya ("Collection of Long Discourses"), mentions only first 12 Mahajanapadas in this list and omits the last four.[7].

Chulla-Niddesa, another ancient text of the Buddhist canon, adds Kalinga to the list and substitutes Yona for Gandhara, thus listing the Kamboja and the Yona as the only Mahajanapadas from Uttarapatha[8] [9][10].

The Jaina Bhagvati Sutra gives a slightly different list of 16 Mahajanapadas: Anga, Banga (Vanga), Magadha, Malaya, Malavaka, Accha, Vaccha, Kochcha (Kachcha?), Padha, Ladha (Lata), Bajji (Vajji), Moli (Malla), Kasi, Kosala, Avaha and Sambhuttara. It is evident that the author of Bhagvati is only interested in the countries of Madhydesa and of the far east and south, since the nations from Uttarapatha, like the Kamboja and Gandhara, are omitted. The more extended horizon of the Bhagvati and its omission of all countries from Uttarapatha clearly shows that the Bhagvati list is of later origin and therefore less reliable[11][12].

Those who drew up these lists of Janapada lists were clearly more concerned with tribal groups than geographical boundaries, since the lists include names of the dynasties or tribes and not of the countries. The Buddhist and Jaina texts refer to the Mahajanapadas only casually and give no historical details about them. The following isolated facts are gleaned from these and other ancient texts containing references to these ancient nations.

Kasi

The Kasis were Aryan people who had settled in the region around Varanasi (formerly called Banaras). The capital of Kasi was at Varanasi, which took its name from the rivers Varuna and Asi which made up its north and south boundaries. Before the time of Buddha, Kasi was the most powerful of the 15 Mahajanapadas. Several Jatakas (folktales about the previous incarnations of Buddha) bear witness to the superiority of its capital over other cities of India and speaks high of its prosperity and opulence. The Jatakas speak of long rivalry of Kasi with Kosala, Anga and Magadha. A struggle for supremacy went on among them for a time. King Brihadratha of Kasi had conquered Kosala, but Kasi was later incorporated into Kosala by King Kansa during Buddha's time. The Kasis along with the Kosalas and Videhans are mentioned in Vedic texts and appear to have been closely allied peoples. Matsya Purana and Alberuni read Kasi as Kausika and Kaushaka respectively; all other ancient texts read Kasi.

Kosala

The country of Kosalas was located to the north-west of Magadha with its capital at Savatthi (Sravasti). It was located about 70 miles to north-west of Gorakhpur and comprised territory corresponding to the modern Awadh (or Oudh) in Uttar Pradesh. It had river Ganga for its southern, river Gandhak for its eastern and the Himalaya mountains for its northern boundaries.

In the Ramayana, Mahabharata and the Puranas the ruling family of the Kosala kingdom was descended from king Ikshvaku. The Puranas give lists of kings of the Aikhsvaka dynasty (the dynasty founded by Ikshvaku) from Ikshvaku to Presenajit (Pasenadi). A Buddhist text, the Majjhima Nikaya ("Middle-length Discourses") mentions Buddha as "a Kosalan"[13] and Mahavira, the 24th Tirthankara of Jainism taught in Kosala. In the time of king Mahakosala, Kashi was an integral part of the kingdom.[14]. Mahakosala was succeeded by his son Pasenadi (Prasenajit), a follower of Buddha. During Pasenadi’s absence from the capital, his minister Digha Charayana raised his son Vidudabha to the throne.[15]. There was a struggle for supremacy between king Pasenadi (Prasenjit) and king Ajatasatru of Magadha which was finally settled once the confederation of Lichchavis became aligned with Magadha. Kosala was ultimately merged into Magadha in the fourth century B.C.E. during the reign of Vidudabha. The chief cities of Kosala were Ayodhya, Saketa, Benares and Sravasti.

Anga

The first reference to the Angas is found in the Atharva-Veda where they are mentioned along with the Magadhas, Gandharis and the Mujavats, all apparently as a despised people. The Jaina Prajnapana ranks Angas and Vangas in the first group of Aryan peoples. Based on Mahabharata evidence, the country of Anga roughly corresponded to the region of Bhagalpur and Monghyr in Bihar and parts of Bengal. The River Champa formed the boundary between the Magadha in the west and Anga in the east; Anga was bounded by river Koshi (Ganga) on the north. According to the Mahabharata, Duryodhana had named Karna the King of Anga. Sabhaparava of Mahabharata (II.44.9) mentions Anga and Vanga as forming one country. The Katha-Sarit-Sagara also attests that Vitankapur, a city of Anga was situated on the shores of the sea; it is possible that the boundaries of Anga extended to the sea in the east.

Anga’s capital Champa, formerly known as Malini, was located on the right bank of river Ganga, near its junction with river Champa. It was a flourishing city, referred to as one of six principal cities of ancient India (Digha Nikaya). It was a great center of trade and commerce and its merchants regularly sailed to distant Suvarnabhumi. Other important cities of Anga were said to be Assapura and Bhadrika.

A great struggle went on between the Angas and its eastern neighbors, the Magadhas. The Vidhura Pandita Jataka describes Rajagriha (the Magadhan Capital) as the city of Anga, and the Mahabharata refers to a sacrifice performed by the king of Anga at Mount Vishnupada (at Gaya). This indicates that Anga had initially succeeded in annexing the Magadhas, and that its borders extended to the kingdom of Matsya. This success of Angas did not last long. About the middle of the sixth century B.C.E., Bimbisara (558 B.C.E. — 491 B.C.E.) the crown prince of Magadha, had killed Brahmadatta, the last independent king of Anga, and seized Champa. Bimbisara made it his headquarters and ruled over it as his father's Viceroy. Anga then became an integral part of the expanding Magadha empire[16].

Magadha

The first reference to the Magadhas (Sanskrit: मगध) occurs in the Atharva-Veda where they are found listed along with the Angas, Gandharis and the Mujavats as a despised people. The bards of Magadha are spoken of in early Vedic literature in terms of contempt. The Vedic dislike of the Magadhas in early times was due to the fact that the Magadhas were not yet wholly Brahmanised.

There is little definite information available on the early rulers of Magadha. The most important sources are the Puranas, the Buddhist Chronicles of Sri Lanka, and other Jain and Buddhist texts, such as the Pali Canon. Based on these sources, it appears that Magadha was ruled by the Śiśunāga dynasty for some 200 years, c. 684 B.C.E. - 424 B.C.E. Rigveda mentions a king Pramaganda as a ruler of Kikata. Yasaka declares that Kikata was a non-Aryan country. Later literature refers to Kikata as synonym of Magadha. With the exception of the Rigvedic Pramaganda, whose connection with Magadha is very speculative, no other king of Magadha is mentioned in Vedic literature. According to the Mahabharata and the Puranas, the earliest ruling dynasty of Magadha was founded by king Brihadratha, but Magadha came into prominence only under king Bimbisara and his son Ajatasatru (ruled 491-461 B.C.E.). The kingdom of Magadha finally emerged victorious in the war of supremacy which went on for a long time among the nations of Majjhimadesa, and became a predominant empire in mid-India.

Two of India's major religions, Jainism and Buddhism, originated in Magadha. Siddhartha Gautama himself was born a prince of Kapilavastu in Kosala around 563 B.C.E., during the Śiśunāga Dynasty. As the scene of many incidents in his life, including his enlightenment, Magadha is often considered a blessed land. Magadha was also the origin of two of India's greatest empires, the Maurya Empire and Gupta Empire, which are considered the ancient Indian "Golden Age" because of the advances that were made in science, mathematics, astronomy, religion, and philosophy. The Magadha kingdom included republican communities such as the community of Rajakumara. Villages had their own assemblies under their local chiefs called Gramakas, and administrations were divided into executive, judicial, and military functions.

The kingdom of the Magadhas roughly corresponded to the modern districts of Patna and Gaya in southern Bihar, and parts of Bengal in the east. It was bounded on the north by river Ganga, on the east by the river Champa, on the south by the Vindhya mountains and on the west by river Sona. During Buddha's time, its boundaries included Anga. Its earliest capital was Girivraja, or Rajagriha in modern Rajgir, in the Patna district of Bihar. The other names for the city were Magadhapura, Brihadrathapura, Vasumati, Kushagrapura and Bimbisarapuri. It was an active center of Jainism in ancient times. The first Buddhist Council was held in Rajagriha in the Vaibhara Hills. Later on, Pataliputra became the capital of Magadha.

Vajji or Vriji

The Vajjians or Virijis included eight or nine confederated clans (atthakula) of whom the Licchhavis, the Videhans, the Jnatrikas and the Vajjis were the most important. Mithila (modern Janakpur in district of Tirhut) was the capital of Videha which became an important center of political and cultural activities in northern India. Videha came into prominence during the reign of King Janaka. The last king of Videha, Kalara, is said to have perished along with his kingdom because of his attempt on a Brahmin maiden. On the ruins of his kingdom arose the republics of Licchhavis, Videhans and seven other small republics.

Around 600 B.C.E. the Licchhavis were disciples of Lord Mahavira (b. 599 B.C.E.), but later they became followers of Buddha, and Buddha is said to have visited the Licchavis on many occasions. The Licchhavis were closely related by marriage to the Magadhas and one branch of Lichhavis dynasty ruled Nepal until start of the Middle Ages, but have nothing to do with current ruling shah dynasty in Nepal. The Licchavis are represented as (Vratya) Kshatriyas in Manusmriti. Vaishali, the headquarters of the powerful Vajji republic and the capital of Lichchavis, was defeated by king Ajatasatru of Magadha.

The territory of the Vajji mahajanapada was located on the north of the Ganga River and extended up to the Terai region of Nepal. On the west, the Gandak River was probably the boundary between it and the Malla mahajanapada, and possibly also separated it from the Kosala mahajanapada. On the east, its territory probably extended up to the forests along the banks of the rivers, Koshi and Mahananda. Vaishali (modern Basarh in Vaishali District of North Bihar), a prosperous town located 25 miles north of river Ganga and 38 miles from Rajagriha, was the capital of Licchhavis and the political headquarters of powerful Varijian confederacy. In the introductory portion of the Ekapanna Jataka, the Vaishali was described as encompassed by a triple wall with the three gates with watch-towers. The Second Buddhist Council was held at Vaishali. Other important towns and villages were Kundapura or Kundagrama (a suburb of Vaishali), Bhoganagara and Hatthigama.[17]

The Vajji Sangha (union of Vajji), which consisted of several janapadas, gramas (villages), and gosthas (groups), was administered by a Vajji gana parishad (people's council of Vajji). Eminent people called gana mukhyas were chosen from each khanda (district) to act as representatives on the council. The chairman of the council was called Ganapramukh (head of the democracy), but was often addressed as the king, though his post was not dynastic. Other executives included a Mahabaladhrikrit (equivalent to the minister of internal security), binishchayamatya (chief justice), and dandadhikrit (other justices).

Malla

Malla was named after the ruling clan of the same name. The Mahabharata (VI.9.34) mentions the territory as the Mallarashtra (Malla state). The Mallas are frequently mentioned in Buddhist and Jain works. They were a powerful clan of Eastern India. Panduputra Bhimasena is said to have conquered the chief of the Mallas in course of his expedition through Eastern India. Mahabharata mentions Mallas along with the Angas, Vangas, and Kalingas, as eastern tribes. The Malla mahajanapada was situated north of Magadha and divided into two main parts with the river Kakuttha (present day Kuku) as the dividing line.

The Mallas were republican people with their dominion consisting of nine territories (Kalpa Sutra; Nirayavali Sutra), one for each of the nine confederated clans. Two of these confederations…one with Kuśināra (modern Kasia near Gorakhpur) as its capital, second with Pava (modern Padrauna, 12 miles from Kasia) as the capital, had become very important at the time of Buddha. Kuśināra and Pava are very important in the history of Buddhism since Buddha took his last meal and was taken ill at Pava and breathed his last at Kusinara. The Jain founder Mahāvīra died at Pava.

The Mallas, like the Lichchhavis, are mentioned by Manusmriti as Vratya Kshatriyas. They are called Vasishthas (Vasetthas) in the Mahapparnibbana Suttanta. The Mallas originally had a monarchical form of government but later they became a Samgha (republic) whose members called themselves rajas. The Mallas were a brave and warlike people, and many of them followed Jainism and Buddhism. The Mallas appeared to have formed an alliance with Lichchhavis for self defense, but lost their independence not long after Buddha's death and were annexed to the Magadhan empire.

The Malla later became an important dynasty in ninth century eastern India.

Chedi or Cheti

The Chedis (Sanskrit: चेदि), Chetis or Chetyas had two distinct settlements of which one was in the mountains of Nepal and the other in Bundelkhand near Kausambi. According to old authorities, Chedis lay near Yamuna midway between the kingdom of Kurus and Vatsas. In the medieval period, the southern frontiers of Chedi extended to the banks of river Narmada. Sotthivatnagara, the Sukti or Suktimati of Mahabharata, was the capital of Chedi. It was ruled during early periods by Paurava kings and later by Yadav kings.

The Chedis were an ancient peoples of India and are mentioned in the Rigveda. Prominent Chedis during the Kurukshetra War included Damaghosha, Shishupala, Dhrishtaketu, Suketu, Sarabha, Bhima's wife, Nakula's wife Karenumati, and Dhristaketu's sons. Other famous Chedis included King Uparichara Vasu, his children, King Suvahu, and King Sahaja. A branch of Chedis founded a royal dynasty in the kingdom of Kalinga according to the Hathigumpha Inscription of Kharvela.

Vamsa or Vatsa

The Vatsas, Vamsas or Vachchas (also known as Batsa, or Bansa) are said to be an offshoot from the Kurus. Vatsa's geographical location was near the confluence of the Ganges and Yamuna rivers, corresponding with the territory of modern Allahabad in Uttar Pradesh. Its capital was Kauśāmbī[18][19], (identified with the modern village of Kosam, 38 miles from Allahabad). Kausambi was a prosperous city and the residence of a large number of wealthy merchants resided. It served as an exchange post for goods and passengers from the north-west and south.

The Puranas state that the Vatsa kingdom was named after a Kaśī king, Vatsa.[20] The Ramayana and the Mahabharata attribute the credit of founding its capital Kauśāmbī to a Chedi prince Kuśa or Kuśāmba. The first ruler of the Bhārata dynasty of Vatsa, about whom some definite information available is Śatānīka II, Parantapa, father of Udayana. Udayana, the romantic hero of the Svapnavāsavadattā, the Pratijñā-Yaugandharāyaṇa and many other legends, was a contemporary of Buddha and of Pradyota, the king of Avanti.[21] According to the Puranas, the four successors of Udayana were Vahināra, DanḍapāṇI, Niramitra and Kṣemaka. Later, the Vatsa kingdom was annexed by the Avanti kingdom. Maniprabha, the great-grandson of Pradyota ruled at Kauśāmbī as a prince of Avanti.[22]

Vatsa had a monarchical form of government based at Kausambi. The Buddha visited Koushambi several times during the reign of Udayana on his effort to spread the dharma, the Eightfold Path and the Four Noble Truths. Udayana was an Upasaka (lay follower) of Buddha, and made Buddhism the state religion. The Chinese translation of the Buddhist canonical text Ekottara Āgama ("Numbered Discourses") states that the first image of Buddha, curved out of sandalwood was made under the instruction of Udayana.

Kuru

The Puranas trace the origin of Kurus from the Puru-Bharata family. Aitareya Brahmana locates the Kurus in Madhyadesha and also refers to the Uttarakurus as living beyond the Himalayas. According to Buddhist text Sumangavilasini (II. p 481), the people of Kururashtra (the Kurus) came from the Uttarakuru. Vayu Purana attests that Kuru, son of Samvarsana of the Puru lineage, was the eponymous ancestor of the Kurus and the founder of Kururashtra (Kuru Janapada) in Kurukshetra. The country of the Kurus roughly corresponded to the modern Thaneswer, union territory of Delhi and Meerut district of Uttar Pradesh. The rivers Aruna, Ashumati, Hiranvati, Apaya, Kausiki, Sarasvati and Drishadvati or Rakshi washed the lands of Kurus.

According to Jatakas, the capital of Kurus was Indraprastha (Indapatta) near modern Delhi, which extended for seven leagues. In Buddha's time, Kuru was ruled by a titular chieftain (king consul) named Korayvya. The Kurus of Buddhist period did not occupy the same position as they had in the Vedic period but continued to enjoy their ancient reputation for deep wisdom and sound health. The Kurus had matrimonial relations with Yadavas, the Bhojas and the Panchalas. There is a Jataka reference to king Dhananjaya introduced as prince from the race of Yudhishtra. Though a well known monarchical people in earlier period, the Kurus are known to have switched to republic form of government during sixth/fifth century B.C.E.. Kautiliya's Arthashastra (4th century B.C.E.) also attests to the Kurus following the Rajashabdopajivin (king consul) constitution.

Panchala

The Panchalas occupied the country to the east of the Kurus between the upper Himalayas and the river Ganga. Panchala roughly corresponded to modern Budaun, Farrukhabad and the adjoining districts of Uttar Pradesh. The country was divided into Uttara-Panchala and Dakshina-Panchala. The northern Panchala had its capital at Adhichhatra or Chhatravati (modern Ramnagar in the Bareilly District), while southern Panchala had it capital at Kampilya or Kampil in Farrukhabad District. The famous city of Kanyakubja or Kanauj was situated in the kingdom of Panchala. Originally a monarchical clan, the Panchals appear to have switched to republican corporation in the sixth and fifth century B.C.E. Fourth century B.C.E. Kautiliya's Arthashastra (4th century B.C.E.) attests to the Panchalas following the Rajashabdopajivin (king consul) constitution.

Panchala had been the second "urban" center of Vedic civilization, as its focus moved east from the Punjab, after the early Iron Age. The Shaunaka and Taittiriya Vedic schools were located in the area of Panchala.

In the Indian Hindu epic Mahabharata, Draupadi (wife of the five Pandava brothers) was the princess of Panchala; Panchali was her other name.

Machcha or Matsya

Matsya or Machcha (Sanskrit for fish), classically called the Mese (IPA: [ˈmiːˌziː]), lay to south of the kingdom of Kurus and west of the Yamuna which separated it from the kingdom of Panchalas. It roughly corresponded to former state of Jaipur in Rajasthan, and included the whole of Alwar with portions of Bharatpur. The capital of Matsya was at Viratanagara (modern Bairat) which is said to have been named after its founder king Virata. In Pāli literature, the Matsya tribe is usually associated with the Surasena. The western Matsya was the hill tract on the north bank of Chambal. A branch of Matsya is also found in later days in Visakhapatnam region.

The Matsya Kingdom was founded by a fishing community. The political importance of Matsya had dwindled by the time of Buddha. King Sujata ruled over both the Chedis and Matsyas thus showing that Matsya once formed a part of Chedi kingdom. King Virata, a Matsya king, founded the kingdom of Virata. The epic Mahabharata refers to as many as six other Matsya kingdoms.

Surasena

Surasenas lay to the southwest of Matsya and west of Yamuna, around the modern Brajabhumi. Its capital was Madhura or Mathura. Avantiputra, the king of Surasena, was the first among the chief disciples of Buddha through whose help, Buddhism gained ground in Mathura country. The Andhakas and Vrishnis of Mathura/Surasena are referred to in the Ashtadhyayi of Panini. Surasena was the sacred land of Lord Krishna in which he was born, raised, and ruled. Kautiliya's Arthashastra relates that the Vrishnis, Andhakas and other allied tribes of the Yadavas formed a Samgha and Vasudeva (Krishna) is described as the Samgha-mukhya. According to Megasthenes, people of this place worshipped the shepherd God Herakles, which according to many scholars was due to a misconception while others see in it connotations of Scythic origin of Yadus.

The Surasena kingdom lost its independence when it was annexed by the Magadhan empire.

Assaka or Ashmaka

Assaka (or Ashmaka) was located on the Dakshinapatha or southern high road, outside the pale of Madhyadesa. In Buddha's time, Assaka was located on the banks of the Godavari river and was the only mahajanapada south of Vindhya mountains. The capital of Assaka was Potana or Potali which corresponds to Paudanya of Mahabharata, and now lies in the Nandura Tehsil. The Ashmakas are also mentioned by Panini and placed in the north-west in the Markendeya Purana and the Brhat Samhita. The River Godavari separated the country of Assakas from that of the Mulakas (or Alakas). The commentator of Kautiliya's Arthashastra identifies Ashmaka with Maharashtra. At one time, Assaka included Mulaka and their country abutted with Avanti.

Avanti

Avanti (Sanskrit: अवन्ति) was an important kingdom of western India and was one of the four great monarchies in India when Buddhism arose, the other three being Kosala, Vatsa and Magadha. Avanti was divided into north and south by the river Vetravati. Initially, Mahissati (Sanskrit Mahishamati) was the capital of Southern Avanti, and Ujjaini (Sanskrit Ujjayini) the capital of northern Avanti, but in the times of Mahavira and Buddha, Ujjaini was the capital of integrated Avanti. The country of Avanti roughly corresponded to modern Malwa, Nimar and adjoining parts of the Madhya Pradesh. Both Mahishmati and Ujjaini were located on the southern high road called Dakshinapatha extending from Rajagriha to Pratishthana (modern Paithan). Avanti was an important center of Buddhism and some of the leading theras and theris were born and resided there. Avanti later became part of the Magadhan empire when King Nandivardhana of Avanti was defeated by king Shishunaga of Magadha.

Gandhara

The wool of Gandharis is referred to in the Rigveda. The Gandharis, along with the Mujavantas, Angas and the Magadhas, are also mentioned in the Atharvaveda, but apparently as "a despised people". Gandharas are included in the Uttarapatha division of Puranic and Buddhistic traditions. Aitareya Brahmana refers to king Naganajit of Gandhara as a contemporary of raja Janaka of Videha. Gandharas were settled from Vedic times along the south bank of river Kubha (Kabol or Kabul River) up to its mouth at the Indus River.[23]Later the Gandharas crossed the Indus and expanded into parts of north-west Panjab. Gandharas and their king figure prominently as strong allies of the Kurus against the Pandavas in Mahabharata war. The Gandharas were well trained in the art of war.

According to Puranic traditions, this Janapada was founded by Gandhara, son of Aruddha, a descendant of Yayati. The princes of this Ghandara are said to have come from the line of Druhyu who was a famous king of Rigvedic period. The river Indus watered the lands of Gandhara. Taksashila and Pushkalavati, the two cities of Ghandara, are said to have been named after Taksa and Pushkara, the two sons of Bharata, a prince of Ayodhya. According to Vayu Purana (II.36.107), the Gandharas were destroyed by Pramiti (Kalika), at the end of Kaliyuga. Panini has mentioned both Vedic form Gandhari as well as the later form Gandhara in his Ashtadhyayi. The Gandhara kingdom sometimes also included Kashmira[24]. Hecataeus of Miletus (549-468) refers to Kaspapyros (Kasyapura i.e Kashmira) as Gandharic city. According to Gandhara Jataka, at one time, Gandhara formed a part of the kingdom of Kashmir. Jataka also gives another name Chandahara for Gandhara.

Gandhara Mahajanapada of Buddhist traditions included territories in east Afghanistan, and north-west of the Panjab (modern districts of Peshawar (Purushapura) and Rawalpindi). Its capital was Takshasila (Prakrit Taxila). The Taxila University was a renowned center of learning in ancient times, attracting scholars from all over the world. The Sanskrit grammarian Panini (flourished c. 400 B.C.E.), and Kautiliya both studied at Taxila University. In the middle of the sixth century B.C.E., King Pukkusati or Pushkarasarin of Gandhara was a contemporary of King Bimbisara of Magadha.

Gandhara was located on the grand northern high road (Uttarapatha) and was a center of international commercial activities. It was an important channel of communication with ancient Iran and Central Asia. According to one school of thought, the Gandharas and Kambojas were cognate people [25] [26] [27][28][29][30]. Some scholars contend that the Kurus, Kambojas, Gandharas and Bahlikas were cognate people and all had Iranian affinities [31][32][33] [34][35]. According to Dr T. L. Shah, the Gandhara and Kamboja were nothing but two provinces of one empire and were located coterminously hence influencing each others language [36]. Naturally, they may have once been a cognate people [37] [38] [39] [40]. Gandhara was often linked politically with the neighboring regions of Kashmir and Kamboja.[41].

Kamboja

Kambojas are also included in the the Uttarapatha division of Puranic and Buddhistic traditions. In ancient literature, the Kamboja is variously associated with the Gandhara, Darada and the Bahlika (Bactria). Ancient Kamboja is known to have comprised regions on either side of the Hindukush. The original Kamboja was a neighbor of Bahlika located in eastern Oxus country, but over time some clans of Kambojas appear to have crossed Hindukush and planted colonies on its southern side. These latter Kambojas are associated with the Daradas and Gandharas in Indian literature and also find mention in the Edicts of Ashoka. The evidence in Mahabharata and in Ptolemy's Geography distinctly supports two Kamboja settlements[42][43][44][45][46]. The cis-Hindukush region from Nurestan up to Rajauri in southwest of Kashmir sharing borders with the Daradas and the Gandharas constituted the Kamboja country [47]. The capital of Kamboja was probably Rajapura (modern Rajori) in south-west of Kashmir. The Kamboja Mahajanapada of the Buddhist traditions refers to this cis-Hindukush branch of ancient Kambojas[48]

The trans-Hindukush region including Pamirs and Badakhshan which shared borders with the Bahlikas (Bactria) in the west and the Lohas and Rishikas of Sogdiana/Fergana in the north, constituted the Parama-Kamboja country[49].

The trans-Hindukush branch of the Kambojas remained pure Iranian but a large section of the Kambojas of cis-Hindukush appears to have come under Indian cultural influence. The Kambojas are known to have had both Iranian as well as Indian affinities[50] [51] There is evidence that the Kambojas used a republican form of government from Epic times. The Mahabharata refers to several Ganah (or Republics) of the Kambojas[52]. Kautiliya's Arthashastra [53] and Ashoka's Edict No. XIII also states that the Kambojas followed a republican constitution. Though Panini's Sutras[54] portray the Kamboja of Panini as a Kshatriya Monarchy, the special rule and the exceptional form of derivative he gives to denote the ruler of the Kambojas implies that the king of Kamboja was only a titular head (king consul).[55].

See also

Notes

- ↑ Vasudeva Sharana Agrawala. India as Known to Pāṇini: A Study of the Cultural Material in the Ashṭādhyāyī. (Lucknow, 1963, 427; India in the Time of Patañjali. 1968, 68

- ↑ Dr. B. N. Puri. India; Socio-economic and Political History of Eastern India. 1977, 9

- ↑ Y. K Mishra. Tribes of Ancient India. (Bihar (India): 1977, 18

- ↑ Mamata Choudhury. Ethnology; Tribal Coins of Ancient India. 2007, xxiv; Devendra Handa. Coins, Indic - 2007. The Journal of the Numismatic Society of India (1972): 221, (Numismatic Society of India).

- ↑ B.C. Law. A History of Pāli Literature. 2000 Ed., 648; B.C. Law, "Some Ksatriya Tribes of Ancient India." Journal Of Ancient Indian History (1924): 230-253.

- ↑ Anguttara Nikaya Vol I. 213; Vol IV, 252, 256, 260, etc.

- ↑ Digha Nikaya, Vol II, 200.

- ↑ Dr Kailash Chand Jain. Lord Mahāvīra and his times. (Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publishers PVT LTD, (1974 1991), 197

- ↑ Dr Ramesh Chandra Majumdar. The History and Culture of the Indian People. (1968), lxv

- ↑ K. D. Sethna. Problems of Ancient India. (New Delhi: Aditya Prakashan. 2000. ISBN 8177420267), 7.

- ↑ Hemchandra Raychaudhuri. Political History of Ancient India. (1972) 1996, 86

- ↑ Ramesh Chandra Majumdar, (gen. ed.) History & Culture of Indian People. Vol. 2 Age of Imperial Unity. (Mumbai: Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan, 1947-1951), 15-16

- ↑ Raychaudhuri, 1972, 88-90

- ↑ Raychaudhuri, 1972, 138

- ↑ Raychaudhuri, 1972, 186

- ↑ Raychaudhuri, 1972/1996

- ↑ Raychaudhuri, 105, 107

- ↑ Geographical Review of India. (Geographical Society of India, 1951) (digitized Original from the University of Michigan), 27 online [1]. Retrieved February 11, 2009.

- ↑ Hermann Kulke, Dietmar Rothermund. A History of India. (Routledge, 2004. ISBN 0415329205), 52 [2]. books.google. Retrieved February 11, 2009.

- ↑ F.E. Pargiter. Ancient Indian Historical Tradition. (Delhi: Motilal Banarasidass, (1972) 1977. ISBN 812081486X), 269-270

- ↑ Raychaudhuri, 119

- ↑ Raychaudhuri, 180, 180n, facing 565

- ↑ German Indologist Dr. Heinrich Zimmer believes the Vaikarana Kurus are from Kashmir

- ↑ Jataka No 406.

- ↑ Ch-Em Ruelle. Revue des etudes grecques. (Paris: Association pour l'encouragement des etudes grecques en France, 1973), 131

- ↑ Rajaram Narayan Saletore. Early Indian Economic History. (London: Curzon, (1973) 1975. ISBN-13: 9780874715996), 237, 324

- ↑ David Gordon White. Myths of the Dog-man. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1991. ISBN 9780226895086), 199, 119; Journal of the Oriental Institute (1919): 200; Journal of Indian Museums (1973): 2, Museums Association of India

- ↑ B. N. Mukherjee. The Pāradas: A Study in Their Coinage and History. (1972), 52; Dr B. N. Mukherjee. The Pāradas. (Calcutta: Pilgrim Publishers, 1972)

- ↑ Journal of the Department of Sanskrit (1989): 50, Rabindra Bharati University, Dept. of Sanskrit- Sanskrit literature; The Journal of Academy of Indian Numismatics & Sigillography (1988): 58, Academy of Indian Numismatics and Sigillography - Numismatics;

- ↑ James George Roche Forlong. Rivers of Life Part 2: Or Sources and Streams of the Faiths of Man in All Lands. (1883) (reprint ed. Kessinger Publishing, 2002. ISBN 0766126404), 114. online [3]. books.google. Retrieved February 11, 2009.

- ↑ Journal of the Oriental Institute, (1919): 265, published by Oriental Institute, Vadodara, India.

- ↑ For Kuru-Kamboja connections, see Dr. Chandra Chakraberty. Literary history of ancient India in relation to its racial and linguistic affiliations. (Calcutta: Vijaya Krishna Bros, 1950?), 14, 37

- ↑ Chandra Chakraberty. The Racial History of India. (1944), 153

- ↑ Chandra Chakraberty. Ethnology

- ↑ Qamarud Din Ahmed. Paradise of Gods. (Karachi, Pakistan: 1966), 330 (in English)

- ↑ Dr T. L. Shah. Ancient India, History of India for 1000 years. (four Vols) Vol I, (1938), 38, 98.

- ↑ Many ancient texts such as Kautiliya's Arthashastra (11.1.1-4) do not mention the Gandharas as separate people from the Kambojas.

- ↑ There are also several instances in the ancient literature where the reference has been made only to the Gandharas and not to the Kambojas. In these cases, the Kambojas have obviously been counted among the Gandharas themselves.

- ↑ The Gandhara and the Kamboja are used interchangeably in the records of the Pala kings of Bengal, thus indicating them to be same group of people.

- ↑ James Fergusson. The Tree and Serpent Worship: Illustrations of Mythology and Art in India in the First and Fourth Centuries after Christ. (1868) (reprint ed. Kessinger Pub. 2004), 47 quote: "In a wider sense, name Gandhara implied all the countries west of Indus as far as Candhahar".

- ↑ Encyclopedia Americana, 1994, 277

- ↑ Ptolemy's Geography mentions Tambyzoi located in eastern Bactria "Ancient India as Described by Ptolemy: Being a Translation of the Chapters…" (1885), 268

- ↑ Dr. Sylvain Levi has identified Tambyzoi with Kamboja. Indian Antiquary.' (1923), 54; Dr Sylvain Lévi. Pre Aryan and Pre Dravidian in India. (1929) republished Asian Educational Service, 1993. ISBN 8120607724), 122

- ↑ Dr Jean Przyluski, Jules Bloch, Asian Educational Services) while land of Ambautai has also been identified by Dr Michael Witzel, (Harvard University) with Sanskrit Kamboja (Electronic Journal of Vedic Studies 5 (1) (September 1999)

- ↑ Edwin Bryant. Indo-Aryan Controversy: Evidence and Inference in Indian History. (RoutledgeCurzon, 2005. ISBN 978-0700714636), 257

- ↑ George Erdosy, (ed.) The Indo-Aryans of Ancient South Asia: Language, Material Culture and Ethnicity. (Walter de Gruyter, 1995. ISBN 978-3110144475), 326,

- ↑ Mahabharata VII.4.5; II.27.23.

- ↑ Sedna, 2000, 5-6

- ↑ Mahabharata II.27.27.

- ↑ Dr Ram Chandra Jain. Ethnology of Ancient Bhārata. (1970), 107

- ↑ Agrawala, 1953/1963, 49

- ↑ Mahabharata 7/91/39.

- ↑ Arthashastra 11/1/4.

- ↑ Ashtadhyayi IV.1.168-175.

- ↑ Dr Kashi Prasad Jayaswal. Hindu Polity: A Constitutional History of India in Hindu Times, Parts I and II. (1955) reprint (Chaukhamba Sanskrit Pratishthan Oriental Publisher, 2006. ISBN 817084312X), 52

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Agrawala, Vasudeva Sharana. India as Known to Pāṇini: A Study of the Cultural Material in the Ashṭādhyāyī. Lucknow, 1963.

- Ahmed, Qamarud Din. Paradise of Gods. Karachi, Pakistan: 1966. (in English)

- Bhandare, S. "Numismatic Overview of the Maurya-Gupta Interlude." in P. Olivelle, ed. Between the Empires: Society in India 200 B.C.E. to 400 C.E. New York: Oxford University Press. 2006. ISBN 0195689356.

- Chakraberty, Chandra. The Racial History of India. 1944.

- Choudhury, Mamata. Ethnology; Tribal Coins of Ancient India. 2007.

- Falk, H., "The Tidal Waves of Indian History." in P. Olivelle, ed. Between the Empires: Society in India 200 B.C.E. to 400 C.E. New York: Oxford University Press. 2006.

- Fergusson, James. The Tree and Serpent Worship: Illustrations of Mythology and Art in India in the First and Fourth Centuries after Christ. (1868) (reprint ed. Kessinger Pub. 2004. ISBN 0766185281.

- Forlong, James George Roche. Rivers of Life Part 2: Or Sources and Streams of the Faiths of Man in All Lands. (1883) (reprint ed. Kessinger Publishing, 2002. ISBN 0766126404.

- Jain, Ramchandra. Ethnology of Ancient Bharata. Varanasi: Chowkhambha Sanskrit. Series Office, 1970.

- Jayaswal, Kashi Prasad. Hindu Polity: A Constitutional History of India in Hindu Times, Parts I and II. (1955) reprint Chaukhamba Sanskrit Pratishthan Oriental Publisher, 2006. ISBN 817084312X.

- Kulke, Hermann, and Dietmar Rothermund. A History of India, 4th ed. Routledge, 2004. ISBN 0415329205.

- Lahiri, B. Indigenous States of Northern India (Circa 300 B.C.E. to 200 C.E. Calcutta: University of Calcutta, 1974.

- Law, B.C., "Some Ksatriya Tribes of Ancient India." in Journal Of Ancient Indian History (1924)

- Law, Bimala Charan. Some Ksatriya Tribes of Ancient India.

Thesis, University of Calcutta. Calcutta: 1924.

- Lévi, Sylvain. Pre Aryan and Pre Dravidian in India. (1929) republished Asian Educational Service, 1993. ISBN 8120607724.

- Mahajan, V.D. Ancient Indian, rev. ed. New Delhi: S. Chand. (1960) 2006. ISBN 8121908876.

- Muller, F. Max. The Dhammapada And Sutta-nipata. Routledge (UK). 2001. ISBN 0700715487.

- Olivelle, Patrick. ed. Between the Empires: Society in India 200 B.C.E. to 400 C.E. New York and Delhi: Oxford University Press. 2006. ISBN 0195689356.

- Pargiter, F.E. Ancient Indian Historical Tradition. (1972)(Delhi: Motilal Banarasidass, 1977. ISBN 812081486X.

- Rawlinson, Hugh George. A Concise History of the Indian People. Oxford University Press. (1950) 1994. ISBN 8185557632.

- Raychaudhuri, H.C. Political History of Ancient India. Calcutta: University of Calcutta. (1972). 2006 ISBN 8130702916.

- Robinson, Francis. The Cambridge Encyclopedia of India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Nepal, Bhutan, and the Maldives. Cambridge [England]: Cambridge University Press. 1989. ISBN 0521334519.

- Sethna, K.D. Problems of Ancient India. Delhi: Aditya, 2000, ISBN 8177420267.

- Singh, M.R. Geographical Data in the Early Puranas. A Critical Study. Calcutta: Punthi Pustak, 1972.

- Thapar, R. Aśoka and the Decline of the Mauryas. New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2001. ISBN 019564445X.

External links

All links retrieved November 5, 2022.

- 16 Mahajanapadas iloveindia.com

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

- Mahajanapadas history

- Kosala history

- Kasi_Kingdom history

- Anga history

- Magadha history

- Malla_(India) history

- Vajji history

- Vatsa history

- Chedi_Kingdom history

- Kuru_(kingdom) history

- Matsya_Kingdom history

- Panchala history

- Assaka history

- Surasena history

- Gandhara history

- Avanti_(India) history

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.