Matthew Calbraith Perry (April 10, 1794 ‚Äď March 4, 1858) was an American naval officer and diplomat who is most famous for his mission to Japan, which opened that country to trade with the West.

Perry began his United States naval career when he was only 15 years old, under the command of his older brother Oliver Hazard Perry. Perry’s first command was schooner USS Cayne that sailed to Africa as part of the United States Navy’s efforts to stop the transatlantic slave trade. He was instrumental as a naval commander in bringing a conclusion to the Mexican-American War. Perry built a reputation for himself as a captain who saw to his crew's health as well as firm discipline. He promoted reforms for training naval officers and for expanding the use of steam power. He was known as the "father of the steam navy."

Perry's most widely acclaimed achievement was his successful diplomatic mission to Japan. His efforts resulted in that island nation opening its shores to another country for the first time in more than two hundred years. This opening would have negative as well as positive consequences. However, it did lead to the rest of the world gaining much from exposure to Japanese culture. A sharing of ingenuity as well as commercial and trading links were formed. Japan, it can be argued, succeeded in retaining many aspects of its own culture while opening itself to the world markets and competing as an economic and technological power at the global level. At the same time, Commodore Perry can be credited fairly with helping to transform the world into a global community and the United States into a world power.

Born in Rocky Brook, Rhode Island, he was the son of Captain Christopher Raymond Perry and the younger brother of Oliver Hazard Perry. Oliver Perry, hero of the Battle of Lake Erie on September 10, 1813, is often quoted by the opening words of his battle report, "We have met the enemy and they are ours."

Matthew Perry obtained a midshipman's commission in the United States Navy in 1809, and was initially assigned to USS Revenge, under the command of his brother Oliver.

Perry's early career saw him assigned to several different ships, including the USS President, where he was aide to Commodore John Rodgers, which was victorious over a British vessel, HMS Little Belt, shortly before the War of 1812 was officially declared. During that war, Perry was transferred to USS United States, and consequently saw little fighting in that war afterward. His ship was trapped by the British blockade at New London, Connecticut. After the war he served on various vessels in the Mediterranean Sea and Africa notably aboard USS Cyane during its patrol off Liberia in 1819-1820. The Cyane was sent to suppress piracy and the slave trade in the West Indies. Later during this period, while in port in Russia, Perry was offered a commission in the Russian navy, which he declined.

Command assignments, 1820s-1840s

Opening of Key West

When England possessed Florida in 1763, the Spanish contended that the Florida Keys were part of Cuba and North Havana. The United States felt the island could potentially be the "Gibraltar of the West" because Key West guarded the northern edge of the 90 mile wide Straits of Florida‚ÄĒthe deep water route between the Atlantic Ocean and the Gulf of Mexico.

In 1815, the governor of Havana, Cuba deeded the island of Key West, Florida to Juan Pablo Salas of Saint Augustine, Florida. After Florida was transferred to the United States, Salas sold the island to U.S. businessman John W. Simonton for $2,000 in 1821. Simonton lobbied the United States Government to establish a naval base on the island, to take advantage of the island's strategic location and to bring law and order to the town.

On March 25, 1822, Perry sailed his next command, the schooner USS Shark to Key West and planted the United States flag, claiming the Florida Keys as American territory.

Perry renamed the island Cayo Hueso as Thompson's Island for the Secretary of the Navy Smith Thompson and its harbor as Port Rodgers for the president of the Board of Navy Commissioners. Rodgers was his superior officer, Commodore John Rodgers. Neither name remained for very long.

From 1826 through 1827 he acted as fleet captain for Commodore Rodgers. Perry returned for shore duty at Charleston, South Carolina in 1828. In 1830 he took command of USS Concord. He spent the years from 1833 to 1837 as second officer of the New York Navy Yard that was later renamed the Brooklyn Navy Yard. Perry was promoted to captain when his assignment there ended.

Perry had a considerable interest in naval education, supporting an apprentice system to train new seamen, and helped establish the curriculum for the United States Naval Academy. He was also a vocal proponent of modernization. Once promoted to captain, in 1837 he oversaw construction of the Navy's second steam frigate, USS Fulton, which he commanded after it was commissioned. He organized the United States' first corps of naval engineers, and conducted the first American Navy gunnery school while commanding USS Fulton in 1839 and 1840 at Sandy Hook on the coast of New Jersey.

Promotion to Commodore

Perry acquired the courtesy title of commodore (then the highest rank in the U. S. Navy) in 1841. Perry was made chief of the Philadelphia Navy Yard in the same year. In 1843, he took command of the African Squadron, whose duty was to interdict the slave trade under the Webster-Ashburton Treaty, and continued in this mission through 1844.

It was not until 1857 the U.S. Congress passed legislation allowing for a ‚ÄúFlag Officer‚ÄĚ and not until 1862 that the rank of ‚ÄúAdmiral‚ÄĚ was introduced.

The Mexican-American War

Organized as early as 1838, Home Squadron ships were assigned, among other duties, to protect coastal commerce, aid ships in distress, suppress piracy and the slave trade, as well as make coastal surveys, and train ships to relieve others on distant stations. In 1845 Commodore David Connor was appointed commander of the United States Home Squadron. Suffering from poor health and aged 54, Connor was considering retirement. However, the coming of the Mexican American War persuaded the American Navy authorities to not change commanders in the face of the war. Perry, who would eventually succeed Connor, was made second-in-command of the Home Squadron and captain USS Mississippi, a side-wheel steamer.

Mexico had no official navy, making the United States Navy's role completely one-sided.[1] The navy quickly blockaded Mexico along its entire coastline of the Gulf of Mexico. With the Mississippi as his flagship, Commodore Perry left Connor's main force of 200 ships and sailed with seven ships for Frontera on the Gulf of Mexico in October 1846. From October 24 to 26 he sailed up the Tabasco River (the present day Grijalva River) and demonstrated naval might against the city of Tabasco. Neither side was able to mount sufficient force to hold Tabasco. Torn between the option of shelling the town to drive out the Mexican Army and disrupting commerce, Perry gave in to the requests of the townspeople ceased the bombardment and withdrew. He then sailed back to the port city of Frontera. Later he returned to Commodore David Connor's main force and took part in the Tampico Expedition which ended when the Navy occupied Tampico in November 1846. In January 1847 needed repairs to the Mississippi forced Perry to return to shipyard at Norfolk, Virginia. Before he sailed for Norfolk, Perry gave six heavy cannons to the United States military commander in the field, General Winfield Scott. These cannons were landed and, by manpower, positioned nearly two miles inland and used to great effect during the siege at Veracruz. At sea, the ship cannon did have sufficient range to reach the entrenched Mexican Army inland and inaccessible at Vera Cruz. (Fairfax 1961, 106)

Perry was still in Norfolk when the amphibious landings on March 9, 1847, took place at Vera Cruz. This was the first large-scale amphibious landing conducted by the United States military. Some reports refer to Commodore Connor's direction of the landing as brilliant and that some 12,000 men and materials where landed within five hours. Perry's return to the United States gave his superiors the chance to give him orders to relieve and succeed Commodore Connor, who was by then suffering from poor health, as commander of the Home Squadron. Perry returned to the fleet during the siege of Vera Cruz and his ship supported the siege from the sea. After the fall of Vera Cruz on March 29, the American force with General Scott moved inland toward Mexico City and Perry moved against the remaining Mexican port cities. Perry assembled the Mosquito Fleet and captured Tuxpan in April 1847. In June 1847 he attacked Tabasco, this time with more favorable results. Perry personally led a 1,173-man assault landing force ashore and captured the city.

The Opening of Japan: 1852-1854

Precedents

Perry's expedition to Japan was preceded by several naval expeditions by American ships:

- From 1797 to 1809, several American ships traded in Nagasaki under the Dutch flag, upon the request of the Dutch who were not able to send their own ships because of their conflict against Great Britain during the Napoleonic Wars.

- In 1837, an American businessman in Canton, China, named Charles W. King saw an opportunity to open trade by trying to return to Japan three Japanese sailors (among them, Otokichi) who had been shipwrecked a few years before on the coast of Oregon. He went to Uraga Channel with Morrison, an unarmed American merchant ship. The ship was attacked several times, and finally sailed back without completing its mission.

- In 1846, Commander James Biddle, sent by the United States Government to open trade, anchored in Tokyo Bay with two ships, including one warship armed with 72 cannons, but his requests for a trade agreement remained unsuccessful.

- In 1848, Captain James Glynn sailed to Nagasaki, leading at last to the first successful negotiation by an American with "Closed Country" Japan. James Glynn recommended to the United States Congress that negotiations to open Japan should be backed up by a demonstration of force, thus paving the way to Perry's expedition.

Background

The Portuguese landed in southern Kyushu, Japan, in 1543 and within two years were making regular port calls. In 1549, a Portuguese Jesuit priest, Francis Xavier, arrived in Kyushu, and, largely due to his influence, Christianity began to have a considerable impact on Japan. The Spanish arrived in 1587, followed by the Dutch in 1609. Tolerance for Christianity disappeared as Japan became more unified and the openness of the period decreased. Strong persecution and suppression of Christianity took place although foreign trade was still encouraged.

By 1616, trade was restricted to Nagasaki and Hirado, an island northwest of Kyushu. In 1635 all Japanese were forbidden to travel outside of Japan or return. The Portuguese were restricted to Deshima, a man-made islet in Nagasaki's harbor measuring 600 by 240 feet, but were then expelled completely by 1638. By 1641, the few Dutch and Chinese foreign contacts were limited to this islet in the Bay of Nagasaki. A small stone bridge connected Deshima to the mainland. A strong guard presence was constantly at the bridge to prevent foreigners entering and Japanese visiting.

The United States wanted to begin trading with Japan because at Japanese ports the American navy and merchant ships could restock coal and supplies. The American whaling fleet also had an interest in the Japanese market.

First visit, 1852-1853

Following the war, American leaders began considering trade with the Far East. Japan was known to be aloof and isolated from the early seventeenth century.[1] The British had established themselves in Hong Kong in 1843 and the Americans feared losing Pacific Ocean access.

Perry was recognized as the only man suitable for the assignment. In his interview for the position, Perry responded by saying; "We will demand as a right, not solicit as a favor, those acts of courtesy due from one civilized nation to another." For two years Perry studied every bit of information on Japan he could find. At the same time he handpicked the officers and men who would sail with him. His concentrations on the crew that would accompany him included only tall men of formal manner and distinctive appearance.

In 1852, Perry embarked from Norfolk, Virginia for Japan, in command of a squadron of ships in search of a Japanese trade treaty. His fleet included the best of American technology. Aboard the black-hulled steam frigate USS Susquehanna (built in 1847), he arrived with the sloops of the line USS Plymouth (1844), USS Saratoga (1842), and the side-wheel steam frigate USS Mississippi (1841) at Edo Bay and sailed into Uraga Harbor near Edo (modern Tokyo) and anchored on July 8, 1853.[1]

Never before had the Japanese seen ships steaming with smoke. When they saw Commodore Perry’s fleet, they thought the ships were "giant dragons puffing smoke." They did not know that steamboats existed and were shocked by the number and size of the guns on board the ships.

Kayama Yezaimon was the daimyo (a powerful feudal leader) of Uraga. On July 8, 1853, with the clang of the warning gongs ringing in his ears, he scanned the horizon. The summer sun was high above the Pacific Ocean when Kayama saw four large ships approaching spouting thick black columns of smoke. As the frigates sailed into Edo bay toward Uraga Harbor, they turned so their guns appeared to bear upon the shore defenses.

Abe Masahiro, head of the Roju (Uraga governing council) studied the oncoming ships through a telescope. The ships remained well beyond the range of his small shore batteries. Yet he could see the reverse was quite untrue. As he watched from his castle wall, a samurai dispatched by Kayama arrived and informed Masahiro that a barbarian fleet blocked the mouth of Edo Bay.

From the forecastle of the leading ship, the sloop of war USS Saratoga, Lieutenant John Goldsborough watched as dozens of Japanese galleys approached the American fleet. They were dramatically decorated with flags and banners. The galleys, reminiscent of ancient Roman Empire ships, were propelled by ten to twenty oars each with two or three men at each oar.[2]

Perry's fleet was met by the representatives of the Tokugawa Shogunate and were told summarily to leave at once and proceed to Deshima in the Bay of Nagasaki, the only Japanese port open to foreigners.

However, Perry refused to leave. He was carrying a special letter from President Millard Fillmore. This letter and other documents requesting trade rights with Japan were prepared on the finest vellum, embellished with government seals and was carried along with other delicate gifts in an ornate gold edged rosewood chest. Perry would deliver the box to no one other than the emperor.

When his fleet was warned to leave, Perry ignored the warning. A Japanese officer with a Dutch interpreter appeared in a small boat alongside the Susquehanna demanding to meet with the ships' commander. The officer was politely told by a petty officer, "The Lord of the Forbidden Interior, could not possibly demean his rank by appearing on deck to carry on a discussion." Astonishing the crewmen on the deck of the Susquehanna, the Japanese officer took no offense; but seemed impressed. When the presence of the vice governor of the shogunate of Uraga was offered, the petty officer responded, "Why did you not bring the governor?" The Japanese officer, history records, was a man of equal mettle. "He is forbidden to be on ships. Would the Lord of the Forbidden Interior designate an officer whose rank was appropriate to conversing with a vice-governor?"[1]

Perry sent a junior lieutenant to join this conversation at the ship's rail. The lieutenant, after a ceremonious exchange of greetings announced that, "the expedition was a most honored one because it carried a message from the President of the United States to the Emperor himself." When the Japanese officer asked if the vice-governor could see this message, Lieutenant Contee told him in all seriousness that, "no one could see it but the emperor or one of his princes. However the governor would be shown a copy of the letter."

The following day the governor, Kayama Yezaimon, sailed out to Perry's flagship on an elaborate barge. Perry had remained completely out of sight during the preceding day's negotiations. He remained secluded sending the Susquehanna’s Captain Buchanan to meet with the governor and carry on the negotiations. The governor, reportedly impressed when he saw the rosewood chest, faltered. He was unsure if the emperor would be best served if he allowed foreigners, gai jin, to land and meet with members of the royal household. Buchanan's well-rehearsed response, "That would indeed be too bad, for the Lord of the Forbidden Interior is committed to delivering the message, or dying in the attempt" had obvious effect. Coupled with this response, earlier that morning, the fleet's guns had been purposely exposed and readied.[1]

Kayama Yezaimon left and returned to shore. Five days later, on July 14, Perry finally allowed himself to be seen. The ships all moved in closer to the harbor. At the appointed moment, Perry appeared on the gleaming deck of his flagship in full military dress. With the aid of a thirteen gun salute, boarded his barge and headed to the onshore pavilion where the properly ranked Prince Idzu awaited with his entourage. One hundred marines in starched dress uniforms had landed beforehand and awaited Perry with a company of seamen and two navy musical bands. Fifteen small boats led his procession slowly and ceremoniously, each mounting a gun. Perry's preparation and attention to detail was paying off. Flanked by two immense black seamen, Perry was led by two midshipmen carrying the rosewood chest.

Scorned by some newspapers in the United Sates as "humbug" insisting the government attend to serious matters, to the Japanese the pomp and pageantry signified that America was a nation worthy of Japan's trade. Knowing that no decision would come in the next days or weeks, Perry in all solemnity told Prince Idzu, "I shall return for an answer within six months."[1]

Japan had for centuries rejected modern technology, and the Japanese military forces could not resist nor refrain from fascination with Perry's modern weaponry. To Japan the "Black Ships" would then become a symbol of Western technology.

Second visit, 1854

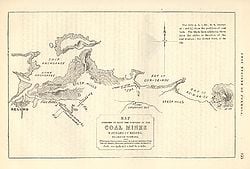

On his way back to Japan, Perry anchored off of Keelung in Formosa, known today as Taiwan, for ten days. Perry and crewmembers landed on Formosa and investigated the potential of mining the coal deposits in that area. He emphasized in his reports that Formosa provided a convenient, mid-way trade location. Perry's reports noted that the island was very defensible and it could serve as a base for exploration in a similar way that Cuba had done for the Spanish in the Americas. Occupying Formosa could help the United States counter European monopolization of the major trade routes. The United States government failed to respond to Perry's proposal to claim sovereignty over Formosa.

Perry returned to Japan in February 1854 with twice as many ships. After a brief standoff, Perry landed on March 8, 1854 to conclude the peace and trade talks. The resultant treaty embodied virtually all the demands in President Fillmore's letter. Perry signed the Convention of Kanagawa on March 31, 1854 and departed for the United States.

Perry had three central objectives in his mission. He succeeded in achieving two. Two ports were now open to America giving access to strategic coal energy resources. He also succeeded in protecting America's then primary source of oil - Pacific Ocean whales. Japan did not open trade with the United States or the west until 1858 when the U.S. Consul, established in Japan as a result of the Kanagawa Treaty, achieved Perry's final objective and established a commercial treaty. The Treaty of Amity and Commerce between the United States and Japan was concluded July 29, 1858.

It is interesting to note the omission of a Japanese signature on the English language version of the Kanagawa Treaty. Perry's letter to the Navy Secretary offers this explanation: "It will be observed that the practice usually pursued in affixing signatures to treaties was departed from on this occasion, and for reason assigned by the Japanese, that their laws forbade the subjects of the Empire from putting their names to any document written in a foreign language." By accepting the treaty with the missing signature Perry's determination to achieve his mission's objectives was tempered by willingness to compromise on issues of custom.[3]

For the first 100 years, the Treaty of Kanagawa represented the origins for the distrust and confrontation that led to American involvement in World War II. However the following decades of cooperation and strategic alliance serve well the memory of the warrior diplomats of the nineteenth century. That they laid aside the tools of war to reach this accord shows the potential for different cultures to find meeting points and live in mutual support.

Barriers lifted

To effect the successful conclusion of the treaty, Commodore Perry assigned senior Naval officers for diplomatic duty rather than allow the negotiations to center upon himself. At the same time, he gathered an impressive naval squadron along with United States Marine Corps ground forces. Perry never had to actually employ these troops but strategically used this force as a counter measure on several occasions.

Another clever tactic Perry took was not allowing himself to be diverted by dealing with low ranking government officials. He had brought an official letter from the President of the United States, Millard Fillmore, to the Emperor of Japan. Although he had invested two years in research for his mission, he proceeded steadily and cautiously. He waited patiently with his armed ships and insisted on dealing only with the highest emissaries of the Emperor.

Perry’s characteristics of working methodically, patiently, and persistently created an environment where there was no expectation of instant success but an incrementally applied effort. Even though Perry’s strategies may have appeared compelling and perhaps aggressive, this framework built his success and produced the results of his mission.

Although Perry has insisted upon meeting with the Japanese Emperor, it was the ruling Japanese shogunate who represented Japan in signing the Convention. The Japanese military leadership was impressed that they were not in a defensible position. They signed the treaties realizing that its long standing isolationist policy would not protect Japan from the threat of war. After long debate finally, on March 31, 1854, the Japanese government and American delegation led by Perry agreed on the Convention of Kangawa.[4] The 1854 Convention of Kanagawa and the United States-Japan Treaty of Amity and Commerce, the "Harris Treaty" of 1858 which followed, allowed for the establishment of foreign concessions, included extra-territoriality for foreigners and minimal import taxes for foreign goods.

The treaty proposed:

- Peace and permanent friendship between the United States and Japan

- Opening of two ports to American ships at Shimoda and Hakodate

- Help for any American ships wrecked on the Japanese coast and protection for shipwrecked persons

- Permission for American ships to buy supplies, coal, water, and other necessary provisions in Japanese ports.

In accordance with Japanese custom, ceremonies and lavish dinners followed the treaty signing. Japanese courtesy and manner made a strong impression on members of the American delegation and their amazement at the rich Japanese culture featured prominently in their reports.

Through his patient and strong approach Commodore Perry was able to dissolve the barriers that separated Japan from the rest of the world. To this day the Japanese celebrate Perry's expedition with annual Black ship festivals. Perry’s hometown of Newport, Rhode Island and Shimoda Japan celebrates a Black Ship festival every year in July. Newport and Shimoda, Japan regard each other as sister cities in tribute to Commodore Perry.

Return to the United States, 1855

Upon Perry's return to the United States in 1855, Congress voted to grant him a reward of $20,000 in appreciation of his work in Japan. Perry used part of this money to prepare and publish a report on the expedition in three volumes, titled Narrative of the Expedition of an American Squadron to the China Seas and Japan.

Last years

Perry died three years later on March 4, 1858 in New York City. His remains were moved to the Island Cemetery in Newport, Rhode Island on March 21, 1866, along with those of his daughter, Anna, who died in 1839.

Side notes

- Perry's middle name is often misspelled as Galbraith.

- Among other mementos, Perry presented Queen Victoria with a breeding pair of Japanese Chin dogs, a breed previously owned only by Japanese nobility.

- A replica of Perry's U.S. flag is on display on board the USS Missouri (BB-63) Memorial in Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. It is attached to the bulkhead just inboard of the Japanese surrender-signing site (1945) on the port side of the ship.

- His wife, Jane Slidell, was the sister of John Slidell. During the American Civil War John Slidell was one of the two CSA diplomats involved in the Trent Affair in November, 1861. The city of Slidell, Louisiana is named after him. Jane Slidell also had another brother, Alexander Slidell Mackenzie, a naval officer, who commanded the USS Somers off the coast of Africa during the Blockade of Africa and was involved in the only incidence of mutiny in the United States Navy resulting in the execution of the alleged mutineers.[5]

Matthew C. Perry's Timeline

- 1794, (April 10) Born in South Kingstown, Rhode Island

- 1809, Embarked in a naval career as midshipman at the age of fifteen.

- 1813, Advanced to the rank of Lieutenant

- 1819-1820, Served on the USS Cyane during its patrol off Liberia to suppress piracy and the slave trade in the West Indies

- 1821‚Äď1825, Commanded the USS Shark

- 1822, (March 25) Planted the United States flag, physically claiming the Florida Keys as American property

- 1826-1827, Acted as fleet captain for Commodore Rodgers

- 1828, Perry returned for shore duty to Charleston, South Carolina

- 1830, Assigned to command the USS Concord

- 1833-1837, Second officer of the New York Navy Yard, which was later renamed the Brooklyn Navy Yard

- 1837, Supervised the construction of first naval steamship, Fulton

- 1837, Promoted to the rank of captain

- 1839-1840, Conducted the first U.S. naval gunnery school while commanding USS Fulton off Sandy Hook on the coast of New Jersey

- 1841, Promoted to the rank of commodore and made chief of the Philadelphia Navy Yard

- 1843-1844, Commanded the African Squadron, which was engaged in suppressing the slave trade

- 1845, Made second-in-command of the Home Squadron and captain of USS Mississippi

- 1846, (October 24 to 26) Sailed up the Tabasco River (the present day Grijalva River) and demonstrated naval might against the city of Tabasco

- 1846, (November) After returning to Commodore David Connor's main force, Perry took part in the Tampico Expedition in which ended when the Navy occupied Tampico

- 1847, (January) Needed repairs to the Mississppi forced Perry to return to shipyard at Norfolk, Virginia His return to the U.S. did give his superiors the chance to finally give him orders to succeed Commodore Connor in command of the Home Squadron

- 1847, (March) Returned to the fleet during the siege of Veracruz and his ship supported the siege from the sea

- 1847, (April) Captured Tuxpan

- 1847, (May) Captured Carmen

- 1847, (June 15-16) Captured last port city on the Gulf coast, San Juan Bautista (present day Villahermosa), capital of Tabasco

- 1853, Perry was sent on a mission by President Millard Fillmore to establish trade with Japan

- 1853, (July) Perry leads a squadron of four ships into Yedo Bay (now Tokyo Bay) and presented representatives of the Japanese Emperor and Prince Idzu with the text of a proposed commercial and friendship treaty. Amid much pomp and pagentry Perry solemnly delivers President Fillmore's proposal and withdraws, stating he will return within six months for an answer.

- 1854, (February) Returned to Japan after exploring alternatives in the China Sea should the treaty with Japan fail. He appears with four sailing ships, three steamers, and 1600 men.

- 1854, (March 8) After a brief standoff, Perry landed for peace and trade talks and began to negotiate with the Japanese to establish a trade agreement.

- 1854, (March 31) Perry signs the Treaty of Kanagawa

- 1855, Perry returned to the United States

- 1856- 1857, Perry published three volume set: Narrative of the Expedition of an American Squadron to the China Seas and Japan

- 1858 (March 4), Perry died in New York City

Notes

- ‚ÜĎ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 Wilbur Cross and John B. Hefferman "Naval Battles and Heroes" in American Heritage (New York: American Heritage Publishing, 1960, ISBN 0060213760), 64-69.

- ‚ÜĎ Commodore Matthew Calbraith Perry Retrieved July 17, 2006.

- ‚ÜĎ Fairfax Davis Downey, "Texas and the War With Mexico" in American Heritage (New York: American Heritage Publishing, 1961, ISBN 006021726X), 106; 111.

- ‚ÜĎ The Treaty of Kanagawa: Setting the Stage for Japanese-American Relations. Retrieved July 17, 2006.

- ‚ÜĎ USS Somers Mutiny 1842. Retrieved July 17, 2006.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Cross, Wilbur and John B. Hefferman. "Naval Battles and Heroes." American Heritage. New York: American Heritage Publishing, 1960, 64-69. ISBN 0060213760

- Downey, Fairfax Davis with Paul M. Angle. "Texas and the War With Mexico." American Heritage. New York: American Heritage Publishing, 1961, 106, 111. ISBN 006021726X

External links

All links retrieved April 29, 2025.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

- Matthew_C_Perry  history

- Home_Squadron  history

- First_Battle_of_Tabasco  history

- Second_Battle_of_Tabasco  history

- Convention_of_Kanagawa  history

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.