Molt

Molting (American English) or moulting (British English) is the routine shedding of the outer covering of an animal, including old feathers in birds, old hairs in mammals, old skin in reptiles, and the entire exoskeleton in arthropods.

In arthropods, such as insects and crabs, molting also is known as ecdysis.

Symbolically, the imagery of molting is used at times as an analogy of personal transformation, such as the molting of one's old self and the emergence of a new and improved person, or the shedding of the body as the human soul transmigrates from one life to another.

Molting in birds

Molting in birds is a comparatively slow process, as a bird never sheds all its feathers at once—it must keep enough feathers to regulate body temperature and repel moisture. However, some species of birds become flightless during an annual "wing molt" and must seek protected habitat with a reliable food supply during that time.

The process of molting in birds is as follows:

- The bird begins to shed some old feathers

- Pin feathers grow in to replace the old feathers

- As the pin feathers become full feathers, other feathers are shed

This is a cyclical process that happens in many phases. Commonly, a molt begins at a bird's head, progresses down the body to its wings and torso, and finishes with the tail feathers.

A molting bird should never have any bald spots. If a pet bird has such bald spots, the bird should be taken to an avian veterinarian to search for possible causes for the baldness, which may include giardia, mites, or feather-plucking.

Molting in mammals

In mammals, the hair, fur, or wool that covers the animal is called a pelage. The pelage provides insulation, concealment on land, buoyancy and streamlining in water, and may be modified for defense or display (Ling 1970). Occasionally replacement or "shedding" of the pelage is essential for survival.

This process of molting in mammals, also called shedding, is true even for marine mammals, such as the pinnipeds (walruses, sea lions, fur seals, and true seals). Molting in mammals includes both shedding of hair and the outer layer of skin, with whales shedding their old skin.

Different pelages occur at different stages in the life history and can relate to varying seasonal requirements dictated by the environment, such as climate, and life processes such as reproduction (Ling 1970). A juvenile pelage is the first coat of hair of a mammal, and it is commonly of fine texture. The post-juvenile molt replaces this fur and gives way to the adult or subadult pelage. Molting is established before sexual maturity and even prenatally, and are inherent features of mammals (Ling 1970).

The pattern of molting varies between species. Some mammals shed their hair year-around, replacing a few hairs at a time, while some molts may be annual or semiannually, such as more strongly in the spring or summer months, or even more regularly. Elephant seals shed hair all at once, called a catastrophic mold. Beluga whales (Delphinapterus leucas) molt each summer, shedding their old yellow skin (Lowry 1994).

Beluga whales tend to rub on coarse gravel to facilitate the removal of their skin, and the skin grows about 100 times faster than normal during the molting period (Lowry 1994).

Molting in reptiles

The most familiar example of molting in reptiles is when snakes "shed their skin." This is usually achieved by the snake rubbing its head against a hard object, such as a rock (or between two rocks) or a piece of wood, causing the already stretched skin to split. At this point, the snake continues to rub its skin on objects, causing the end nearest the head to peel back on itself, until the snake is able to crawl out of its skin, effectively turning the molted skin inside-out. This is similar to how you might remove a sock from your foot by grabbing the open end and pulling it over itself. The snake's skin is often left in one piece after the molting process.

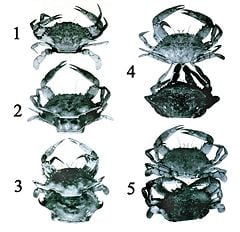

In arthropods, such as insects, arachnids and crustaceans, molting is the shedding of the exoskeleton, or cuticle, typically to let the organism grow. The exoskeleton is a hard, inert, outer structure that supports and protects the animal. For some arthropods, it is referred to commonly as a shell.

The molting process is often termed ecdysis. Ecdysis can be defined as the molting or shedding of the cuticula in arthropods and the related groups that together make up the Ecdysozoa. The Ecdysozoa are a group of protostome animals that includes Arthropoda, Nematoda, and several smaller phyla. The most notable characteristic shared by ecdysozoans is a three-layered cuticle composed of organic material, which is periodically molted as the animal grows. This process gives the group its name.

The exoskeleton, or cuticle, is well-defined and is secreted by, and strongly attached to, the underlying epidermal cells (Ewer 2005). Since the cuticula of these animals is also the skeletal support of the body and is inelastic, unable to grow like skin, it is shed during growth and a new, larger covering is formed. The new exoskeleton that is secreted by the epidermis is initially soft and remains so until the outer cuticle is shed at ecdysis. The new cuticle expands and hardens after the molting of the old exoskeleton.

After molting, an arthropod is described as teneral—it is fresh pale, and soft-bodied. Within a short time, sometimes one or two hours, the cuticle hardens and darkens following a tanning process similar to that of the tanning of leather. It is during this short phase that the animal grows, since growth is otherwise constrained by the rigidity of the exoskeleton.

Ecdysis may also enable damaged tissue and missing limbs to be regenerated or substantially re-formed, although this may only be complete over a series of molts, the stump being a little larger with each molt until it is of normal, or near normal size again.

Process

In preparation for ecdysis, the arthropod becomes inactive for a period of time, undergoing apolysis (separation of the old exoskeleton from the underlying epidermal cells). For most organisms, the resting period is a stage of preparation during which the secretion of fluid from the molting glands of the epidermal layer and the loosening of the underpart of the cuticula occur.

Once the old cuticle has separated from the epidermis, the digesting fluid is secreted into the space in between them. However, this fluid remains inactive until the upper part of the new cuticula has been formed.

While the old cuticula is being digested, the new layer is secreted. All cuticular structures are shed at ecdysis, including the inner parts of the exoskeleton, which includes terminal linings of the alimentary tract and of the tracheae if they are present.

Then, by crawling movements, the animal pushes forward in the old integumentary shell, which splits down the back allowing the animal to emerge. Often, this initial crack is caused by an increase in blood pressure within the body (in combination with movement), forcing an expansion across its exoskeleton, leading to an eventual crack that allows for certain organisms, such as spiders, to extricate themselves.

Molting in insects

Each stage in the development of an insect between molts is called an instar, or stadium. Higher insects tend to have fewer instars (four to five) than lower insects (anywhere up to about 15). Higher insects have more alternatives to molting, such as expansion of the cuticle and collapse of air sacs to allow growth of internal organs.

The process of molting in insects begins with the separation of the cuticle from the underlying epidermal cells (apolysis) and ends with the shedding of the old cuticle (ecdysis). In many of them, it is initiated by an increase in the hormone ecdysone. This hormone causes:

- apolysis - the separation of the cuticle from the epidermis

- excretion of new cuticle beneath the old

- degradation of the old cuticle

After apolysis, molting fluid is secreted into the space between the old cuticle and the epidermis (the exuvial space). This fluid contains inactive enzymes that are activated only after the new epicuticle is secreted. This prevents them from digesting the new procuticle as it is laid down. The lower regions of the old cuticle—the endocuticle and mesocuticle—are then digested by the enzymes and subsequently absorbed. The exocuticle and epicuticle resist digestion and are hence shed at ecdysis.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Ewer, J. How the ecdysozoan changed its coat. PLos Biology 3(10): e349, 2005. Retrieved July 23, 2007.

- Lowry, L. Beluga whale. Wildlife Notebook Series (Alaska Dept. of Fish and Game). 1994.

- Ling, J. K. “Pelage and molting in wild mammals with special reference to aquatic forms.” The Quarterly Review of Biology 45(1): 16-54, 1970.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.