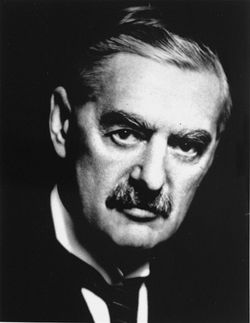

Neville Chamberlain

Arthur Neville Chamberlain (March 18, 1869 – November 9, 1940), known as Neville Chamberlain, was a British Conservative politician and prime minister of the United Kingdom from 1937 to 1940.

Chamberlain is perhaps the most ill-regarded British prime minister of the twentieth century in the popular mind internationally because of his policy of appeasement towards Nazi Germany regarding the abandonment of Czechoslovakia to Hitler at Munich in 1938. In the same year he also gave up the Irish Free State Royal Navy ports, in practice making it safe for German submarines to stay about two hundred miles west of the Irish coast, where they could attack merchant shipping at will.

In 1918, after serving in local politics and as lord mayor of Birmingham, Chamberlain joined his father (also a former mayor of Birmingham) and his half brother in Parliament at the age of 49. He declined a junior ministerial position, remaining a backbencher until he was appointed postmaster general after the 1922 general election. He was rapidly promoted secretary of state for health, then as chancellor of the exchequer, but presented no budget before the government fell in 1924. Again minister of health (1924-1929), he introducing a range of reform measures from 1924 to 1929 before returning to the exchequer in the coalition National Government in 1931, where he spent six years reducing the war debt and the tax burden. When Stanley Baldwin retired after the abdication of Edward VIII and the coronation of George VI, Chamberlain took his place as prime minister in 1937.

His political legacy is overshadowed by his dealings with and appeasement of Nazi Germany. He signed the Munich Agreement with Hitler in 1938, which effectively allowed Germany to annex the Czech Sudetenland. Shortly thereafter, Hitler occupied the remainder of Czechoslovakia, technically his first International aggression, and the first step on the road to World War II. Chamberlain entered into a Mutual Defense Pact with Poland, but was unable to do anything directly when Germany invaded it six days later on September 1, 1939. Nevertheless, Chamberlain delivered an ultimatum to Hitler, declared war on Germany on September 3 and launched attacks on German shipping on September 4. During the period now known as "The Phoney War" until May 1940, Chamberlain sent a 300,000 strong British Expeditionary Force to Belgium, which later had to be ignominiously rescued from the beaches of Dunkirk.

On May 10, 1940, he was forced to resign after Germany invaded the Netherlands, Belgium and France, and was succeeded by Winston Churchill. He died of cancer six months after leaving office. His policy of appeasement remains controversial. This stemmed both from a personal horror of war and from a genuine belief that a lasting peace could be built and from a commitment to diplomacy over and against confrontation. So many of his own friends had lost their lives in World War I that he really did want that war to be the war that ended all wars.

Early life

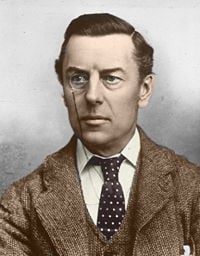

Born in Birmingham, England, Chamberlain was the eldest son of the second marriage of Joseph Chamberlain and a half-brother to Austen Chamberlain. Joseph's first wife had died shortly after giving birth to Austen. Neville's mother also died in childbirth in 1875, when Neville was six years old.

Chamberlain was educated at Rugby School, but the experience unsettled him and he became rather shy and withdrawn during his time there. At first he declined to join the school debating society, changing his mind only in 1886 when he spoke in favor of preserving the United Kingdom, agreeing with his Liberal Unionist father's opposition over Irish Home Rule. During this period Chamberlain developed a love of botany, later becoming a fellow of the Royal Horticultural Society. He was also fascinated by ornithology and fishing. Chamberlain had a passion for music and literature, and in later life would often quote William Shakespeare in the public debates of the day.

After leaving school, Chamberlain studied at Mason Science College (later the University of Birmingham) where he took a degree in science and metallurgy. Shortly after graduation he was apprenticed to an accounting firm.

In 1890, Joseph Chamberlain's finances took a downturn, and he decided, against better advice from his brothers, to try growing sisal in the Bahamas. Neville and Austen were sent to the Americas to investigate the island of Andros, which seemed a good prospect for a plantation, but the crops failed in the unsuitable environment, and by 1896 the business was shut down at a heavy loss.

Neville Chamberlain's later ventures at home were more successful. He served as chairman of several manufacturing firms in Birmingham, including Elliots, a metal goods manufacturer, and Hoskins, a cabin berth manufacturer. He gained a reputation for being a hands-on manager, taking a strong interest in the day-to-day running of affairs.

Lord Mayor of Birmingham

Although he had campaigned for his father and brother, it was in November 1911 that he entered politics himself when he was elected to Birmingham City Council. He immediately became chairman of the Town Planning Committee. That January, he began a devoted marriage to Anne Vere Cole, with whom he had two children, Dorothy Ethel (1911-1994) and Francis Neville (1914-1965). Under Chamberlain's direction, Birmingham adopted one of the first town planning schemes in Britain. In 1913 he took charge of a committee looking at housing conditions. The interim report of the committee could not be implemented immediately because of the war, but it did much to show Chamberlain's vision of improvements to housing.

In 1915 he became lord mayor of Birmingham. Within the first two months, he had won government approval to increase the electricity supply, organized the use of coal as part of the war effort and had prevented a strike by council workers. During this time he assisted in the creation of the Birmingham Symphony Orchestra, now world-class, and the establishment of the Birmingham Municipal Bank, the only one of its type in the country, which aimed to encourage savings to pay for the war loan. The bank proved highly successful and lasted until 1976, when it merged with the TSB (now Lloyds-TSB). Chamberlain was re-elected lord mayor in 1916. He did not complete his term, instead moving to a government post in London.

Early ministerial career

In December 1916, David Lloyd George in London offered Chamberlain the new post of director of national service, to which several people including Chamberlain’s half-brother Austen had recommended him. The director was responsible for co-coordinating conscription and ensuring that essential war industries were able to function with sufficient workforces. Despite several interviews, however, Chamberlain was unclear about many aspects of the job and it proved to be very difficult to recruit volunteers to work in industry. He clashed several times with Lloyd George, who had taken a strong dislike to him, which added to his difficulties. Chamberlain resigned in 1917. He and Lloyd George retained a mutual contempt that would last throughout their political careers.

Embittered by his failure, Chamberlain decided to stand in the next general election and was elected for Birmingham Ladywood. He was offered a junior post at the Ministry of Health, but declined it, refusing to serve a Lloyd George government. He also declined a knighthood. Chamberlain spent the next four years as a Conservative backbencher, despite his half-brother Austen becoming leader of Conservative MPs in 1921.

In October 1922, discontent amongst Conservatives against the Lloyd George Coalition Government resulted in the majority of MPs leaving the coalition, even though it meant abandoning their current leadership, as Austen had pledged to support Lloyd George. Fortuitously for Neville, he was on his way home from Canada at the time of the meeting, and so not forced to choose between supporting his brother's leadership and bringing down a man he despised.

In 1922, the Conservatives won the general election. The new Conservative prime minister, Andrew Bonar Law, offered Chamberlain the position of postmaster general. After consulting his family on whether he should accept, he did so. He was also created a Privy Councillor, becoming the "Right Honourable." Within a few months he earned a reputation for his abilities and skill, and was soon promoted to the Cabinet as minister of health. In this position, he introduced the Housing Act of 1923 that provided subsidies for private companies building affordable housing as a first step towards a program of slum clearances. He also introduced the Rent Restriction Act, which limited evictions and required rents to be linked to the property's state of repair. Chamberlain's main interest lay in housing, and becoming the minister of health gave him a chance to spread these ideas on a national basis. These ideas stemmed from his father, Joseph Chamberlain.

When Stanley Baldwin became prime minister four months later, he promoted Chamberlain to chancellor of the exchequer, a position which he held until the government fell in January 1924. His first chancellorship was unusual in that he presented no budget.

Becoming the heir apparent

In the 1929 general election, Chamberlain changed his constituency from Birmingham Ladywood to a safer seat, Birmingham Edgbaston, and held it easily, but the Conservative Party lost the election to Labour and entered a period of internal conflict. In 1930 Chamberlain became chairman of the Conservative Party for a year and was widely seen as the next leader. However, Baldwin survived the conflict over his leadership and retained it for another seven years. During this period, Chamberlain founded and became the first head of the Conservative Research Department.

During these two years out of power, Baldwin's leadership came in for much criticism. Many in politics, Conservative or otherwise, urged the introduction of protective tariffs, an issue which had caused conflict on and off for the last 30 years. Chamberlain was inclined towards tariffs, having a personal desire to see his father's last campaign vindicated. The press baron Lord Beaverbrook launched a campaign for "Empire Free Trade," meaning the removal of tariffs within the British Empire and the erection of external tariffs; he was supported in his opposition to Baldwin by Lord Rothermere, who also opposed Baldwin's support for Indian independence. Their main newspapers, the Daily Express and Daily Mail respectively, criticized Baldwin and stirred up discontent within the party. At one point, Beaverbrook and Rothermere created the United Empire Party, which stood in by-elections and tried to get Conservatives to adopt its platform. Chamberlain found himself in the difficult position of supporting his leader, even though he disagreed with Baldwin's handling of the issue and was best placed to succeed if he did resign. Baldwin stood his ground, first winning a massive vote of confidence within his party and then taking on the challenge of the United Empire Party at the Westminster St. George's by-election in 1931. The official Conservative candidate was victorious, and Chamberlain found his position as the clear heir to Baldwin established, especially after Churchill's resignation from the Conservative Business Committee over Indian home rule.

Despite now being a national figure, Chamberlain almost lost Ladywood to his Labour challenger, winning, after several recounts by 77 votes—but he faced a significant challenge in the new government. Chamberlain declined a second term as chancellor of the exchequer, choosing to become minister of health again.

Between 1924 and 1929 he successfully introduced 21 pieces of legislation, the boldest of which was perhaps the Rating and Valuation Act 1925, which radically altered local government finance. The act transferred the power to raise rates from the Poor Law boards of guardians to local councils, introduced a single basis and method of assessment for evaluating rates, and enacted a process of quinquennial valuations. The measure established Chamberlain as a strong social reformer, but it angered some in his own party. He followed it with the Local Government Act 1929, which abolished the boards of guardians altogether, transferring their powers to local government and eliminating workhouses. The act also eliminated rates paid by agriculture and reduced those paid by businesses, a measure forced by Winston Churchill and the Exchequer; the result was a strong piece of legislation that won Chamberlain many acclaims. Another prominent piece of legislation was the Widows, Orphans, and Old Age Pensions Act 1925, which did much to foster the development of the embryonic Welfare State in Britain.

Formation of the National Government

The Labour Government faced a massive economic crisis as currencies collapsed and speculators turned towards the United Kingdom. Matters were not helped by the publication of the May Report, which revealed that the budget was unbalanced. The revelation triggered a crisis of confidence in the pound, and Labour ministers grappled with the proposed budget cuts. Given the possibility that the government could fall, Prime Minister Ramsay MacDonald met regularly with delegations from both the Conservatives and Liberals. Baldwin spent much of the summer in France, so Chamberlain was the primary leader of the Conservative delegation. He soon came to the conclusion that the best solution was a National Government comprised of politicians drawn from all parties. He also believed that a National Government would have the greatest chance of introducing tariffs. As the political situation deteriorated, Chamberlain argued strongly for coalition, eventually convincing both leaders that this was the best outcome. King George V and the acting Liberal leader Sir Herbert Samuel, among others, were also convinced. Finally, on 24 August 1931, the Labour government resigned and MacDonald formed a National Government. Chamberlain once more returned to the Ministry of Health with the specific task of encouraging local authorities to make cuts to their expenditure.

Return to the Exchequer

After the 1931 general election, Chamberlain again became chancellor of the exchequer. As chancellor, Chamberlain hoped to introduce protective tariffs, but the economic situation threatened government unity; at the general election, the parties supporting the government had agreed to ask for a "Doctor's mandate" to enact any legislation necessary to resolve the economic situation. Now the government, made up of Conservatives, Liberals, National Labour, and Liberal Nationals, faced a major crisis. The government agreed that no immediate steps would be taken; instead, the issue was referred to a subcommittee of the Cabinet—whose members were largely in favor of tariffs. In the meantime, Chamberlain introduced the Abnormal Importations Bill, which allowed temporary duties to be imposed if importers seemed to be taking advantage of government delays.

The Cabinet committee reported in favor of introducing a general tariff of ten percent, with exceptions for certain goods such as produce from the dominions and colonies, as well as higher tariffs for excessively high imports or for particular industries which needed safeguarding. In addition, the government would negotiate with dominion governments to secure trading agreements within the British Empire, promoting Chamberlain's father's vision of the Empire as an economically self-sufficient unit. The Liberals in the Cabinet, together with Lord Snowden (1864-1937), the first Labour Chancellor, refused to accept this and threatened resignation. In an unprecedented move, the government suspended the principle of collective responsibility and allowed the free-traders to publicly oppose the introduction of tariffs without giving up membership in the government. This move had kept the National Government together at this stage, but Chamberlain would have preferred to force the Liberals' resignations from the government, despite his reluctance to lose Snowden. When he announced the policy in the House of Commons on February 4, 1932, he used his father's former dispatch box from his time at the Colonial Office and made great play in his speech of the rare moment when a son was able to complete his father's work. At the end of his speech, Austen walked down from the backbenches and shook Neville's hand amidst great applause.

Later that year, Chamberlain traveled to Ottawa, Canada, with a delegation of Cabinet ministers who intended to negotiate free trade within the empire. The resulting Ottawa Agreement did not meet expectations, as most dominion governments were reluctant to allow British goods in their markets. A series of bilateral agreements increased the tariffs on goods from outside the empire even further, but there was still little direct increase in internal trade. The agreement was sufficient, however, to drive Snowden and the Liberals out of the National Government; Chamberlain welcomed this, believing that all the forces supporting the government would eventually combine into a single "National Party."

Chamberlain remained Chancellor until 1937, during which time he emerged as the most active minister of the government. In successive budgets he sought to undo the harsh budget cuts of 1931 and took a lead in ending war debts, which were finally cancelled at a conference at Lausanne in 1932. In 1934, he declared that economic recovery was under way, stating that the nation had "finished Hard Times and could now start reading Great Expectations." However, from 1935 on, financial strains grew as the government proceeded on a program of rearmament.

Chamberlain now found himself under attack on two fronts: Winston Churchill accused him of being too frugal with defense expenditure while the Labour Party attacked him as a warmonger. In the 1937 budget, Chamberlain proposed one of his most controversial taxes, the National Defense Contribution, which would raise revenue from excessive profits in industry. The proposal produced a massive storm of disapproval, and some political commentators speculated that Chamberlain might leave the Exchequer, not for 10 Downing Street, but for the backbenches.

Despite these attacks from the Labour Party and Churchill, Chamberlain had adopted a policy, called Rationalization, which would prove vital to Britain during wartime. Under this policy the government bought old factories and mines. This was a gradual process as the depression had hit Britain hard. Then the factories were destroyed. Gradually, newer and better factories were built in their place. They were not to be used when Britain was in a state of depression. Rather, Chamberlain was preparing Britain for the time when Britain would emerge out of the depression. By 1938 Britain was in the best position for rearmament, as thanks to this policy Britain had the most efficient factories in the world with the newest technology. This meant that Britain was able to produce the best weapons fastest, and with the best technology.

Appointment as prime minister

Despite financial controversies, when Baldwin retired after the abdication of Edward VIII and the coronation of George VI, it was Chamberlain who was invited to "kiss hands"[1] and succeed him. He became prime minister of the United Kingdom on May 28, 1937, and leader of the Conservative Party a few days later.

Chamberlain was a Unitarian and did not accept the basic trinitarian belief of the Church of England, the first prime minister to officially reject this doctrine since the Duke of Grafton. This did not bar him from advising the king on appointments in the established church.

Chamberlain's ministerial selections were notable for his willingness to appoint without regard for balancing the parties supporting the National Government. He was also notable for maintaining a core of ministers close to him who agreed strongly with his goals and methods, and for appointing a significant number of ministers with no party political experience, choosing those with experience from the outside world. Such appointments included the law lord, Lord Maugham as lord chancellor; the former first sea lord, Lord Chatfield as minister for coordination of defence, the businessman Andrew Duncan as president of the Board of Trade; the former director-general of the BBC Sir John Reith as minister of information, and the department store owner Lord Woolton as minister of food. Even when appointing existing MPs, Chamberlain often ignored conventional choices based on service and appointed MPs who had not been in the House of Commons very long, such as the former civil servant and Governor of Bengal, Sir John Anderson, who became the minister in charge of air raid precautions; or the former president of the National Farmers Union, Sir Reginald Dorman-Smith, who was made minister of agriculture.

Domestic policy

Chamberlain's domestic policy, which receives little attention from historians today, was considered highly significant and radical at the time. Achievements included the Factory Act 1937, which consolidated and tightened many existing measures and sought to improve working conditions by limiting the number of hours that minors and women could work and setting workplace regulation standards. The Housing Act 1938 provided subsidies that encouraged slum clearance and the relief of overcrowding, as well as maintaining rent controls for cheap housing. The Physical Training Act 1937 promoted exercise and good dieting and aimed for a compulsory medical inspection of the population. The Coal Act 1938 nationalized mining royalties and allowed for the voluntary amalgamation of industries. Passenger air services were made into a public corporation in 1939. The Holidays with Pay Act 1938 gave paid holidays to over eleven million workers and empowered the Agricultural Wages Boards and Trade Boards to ensure that holidays were fixed with pay. In many of these measures Chamberlain took a strong personal interest. One of his first actions as prime minister was to request two-year plans from every single department, and during his premiership he would make many contributions.

Few aspects of domestic policy gave Chamberlain more trouble than agriculture. For years, British farming had been a depressed industry; vast sections of land went uncultivated while the country became increasingly dependent upon cheap foreign imports. These concerns were brought to the forefront by the National Farmers Union, which had considerable influence on MPs with rural constituencies. The union called for better protection of tariffs, for trade agreements to be made with the consent of the industry, and for the government to guarantee prices for producers. In support, Lord Beaverbrook's Daily Express launched a major campaign for the country to "Grow More Food," highlighting the "idle acres" that could be used. In 1938, Chamberlain gave a speech at Kettering in which he dismissed the Beaverbrook campaign, provoking an adverse reaction from farmers and his parliamentary supporters.

In late 1938, Chamberlain and his Minister of Agriculture William Shepherd Morrison proposed a Milk Industry Bill that would set up ten trial areas with district monopolies of milk distribution, create a Milk Commission, cut or reduce subsidies for quality milk, butter, and cheese, and grant local authorities the power to enforce pasteurisation. Politicians and the milk industry reacted unfavorably to the bill, fearing the level of state control involved and the possible impact on small dairies and individual retailers. The Milk Marketing Board declared itself in favor of amendments to the bill, a rare move; at the start of December, the government agreed to so radically redraft the bill as to make it a different measure. Early in 1939, Chamberlain moved Morrison away from the Ministry of Agriculture and appointed as his successor Sir Reginald Dorman-Smith, MP for Petersfield and a former president of the National Farmers Union. Dorman-Smith was hailed as bringing greater expertise to the role, but developments were slow; after war had broken out, there were many who still felt the country was not producing sufficient food to overcome the problems of restricted supplies.

Other proposed domestic reforms were cancelled outright when the war began, such as the raising of the school leaving age to 15, which would have otherwise commenced on September 1, 1939, were it not for the outbreak of World War II. The home secretary, Sir Samuel Hoare, proposed a radical reform of the criminal justice system, including the abolition of flogging, which was also put on hold. Had peace continued and a general election been fought in 1939 or 1940, it seems likely that the government would have sought to radically extend the provision of pensions and health insurance while introducing family allowances.

Relations with Ireland

When Chamberlain became prime minister, relations between the United Kingdom and the Irish Free State had been heavily strained for some years. The government of Eamon de Valera, seeking to transform the country into an independent republic, had proposed a new constitution, Bunreacht na hÉireann. The constitution was adopted at the end of 1937, turning the Free State into Éire, an internally republican state which only retained the monarchy as an organ for external relations. The British government accepted the changes, formally stating that it did not regard them as fundamentally altering the position of Ireland within the Commonwealth of Nations.

De Valera also sought to overturn other aspects of the Anglo-Irish Treaty, most notably the partition that had created Northern Ireland, as well as seeking to reclaim control of the three "Treaty Ports" which had remained in British control. Chamberlain, mindful of the deteriorating European situation, the desirability of support from a friendly neutral Ireland in time of war, and the difficulty of using the ports for defense if Ireland was opposed, wished to achieve peaceful relations between the two countries. The United Kingdom was also claiming compensation from Ireland, a claim whose validity the Free State strongly disputed.

Chamberlain, Secretary of State for Dominion Affairs Malcolm MacDonald, and de Valera held a conference starting in January 1938 in an attempt to resolve the other conflicts between their countries. De Valera hoped to secure, at the very least, the British government's neutrality on the matter of ending partition, but the devolved government of Northern Ireland was implacably opposed to any attempt to create a united Ireland. In February 1938, a Northern Ireland general election gave Lord Craigavon's government an increased majority, strengthening the Unionists' hand and making it difficult for the government to make any concessions. Despite this, de Valera proved willing to discuss the other points of contention.

The result of the conference was a strong and binding trade agreement between the two countries. Britain agreed to hand over the treaty ports to Irish control, while Ireland agreed to pay Britain £10 million with wider claims cancelled. The loss of the treaty ports meant that the British Navy was restricted to a patrolling range some 200 miles west of Ireland in the Atlantic. This meant that German submarines could operate with impunity in the Atlantic until the 1943 development of airborne marine microwave radar, something that could not have been predicted or relied upon in 1938. This was a very serious tactical error, and was strongly derided by Winston Churchill in the House of Commons (who had built the treaty ports into the 1921 agreement precisely for the reasons of possible submarine warfare against Germany). Being able to refuel anti-submarine ships from the Irish coast would have saved thousands of merchant marine lives on the British and American sides. No settlement on partition was reached, and Chamberlain's hopes of being able to establish munitions factories in Ireland were not realized during the Second World War, but the two countries also issued a formal expression of friendship.

The agreement was criticized at the time and subsequently by Churchill, but he was the lone voice of dissent; the diehard wing of the Conservative Party was no longer willing to fight over the issue of Ireland. Others have pointed out that the issue's resolution resulted in Ireland taking a stance of benevolent neutrality during the Second World War (known in Ireland as “The Emergency”), and recent evidence has shown the extent to which the state helped the United Kingdom.

Palestine White Paper

One of the greatest controversies of Chamberlain's premiership concerned the government's policy on the future of the British Mandate of Palestine. After successive commissions and talks had failed to achieve a consensus, the government argued that the statements in the Balfour Declaration (1917) (that it "view[ed] with favour" a "national home" for Jews in Palestine) now had been achieved since over 450,000 Jews had immigrated there. The MacDonald White Paper of 1939, so named after the secretary of state for the colonies, Malcolm MacDonald, was then introduced. It proposed a quota of 75,000 further immigrants for the first five years, with restrictions on the purchase of land.

The White Paper caused a massive outcry, both in the Jewish world and in British politics. Many supporting the National Government were opposed to the policy on the grounds that they claimed it contradicted the Balfour Declaration. Many government MPs either voted against the proposals or abstained, including Cabinet Ministers such as the Jewish Leslie Hore-Belisha.

European policy

As with many in Europe who had witnessed the horrors of the First World War and its aftermath, Chamberlain was committed to peace at any price short of war. The theory was that dictatorships arose where peoples had grievances, and that by removing the source of these grievances, the dictatorship would become less aggressive. It was a popular belief that the Treaty of Versailles was the underlying cause of Hitler's grievances. Chamberlain, as even his political detractors admitted, was an honorable man, raised in the old school of European politics. His attempts to deal with Nazi Germany through diplomatic channels and to quell any sign of dissent from within, particularly from Churchill, were called by Chamberlain "the general policy of appeasement" (June 7, 1934).

The first crisis of Chamberlain's tenure was over the annexation of Austria. The Nazi government of Adolf Hitler had already been behind the assassination of one chancellor of Austria, Engelbert Dollfuss, and was pressuring another to surrender. Informed of Germany's objectives, Chamberlain's government decided it was unable to stop events, and acquiesced to what later became known as the Anschluss.

Following the historic meeting in Munich with Hitler, Chamberlain famously held aloft the paper containing the resolution to commit to peaceful methods signed by both Hitler and himself on his return from Germany to London in September 1938. He said:

My good friends, for the second time in our history, a British Prime Minister has returned from Germany bringing peace with honour. I believe it is peace for our time.

The second crisis came over the Sudetenland area of Czechoslovakia, which was home to a large German minority. The Munich Agreement, engineered by the French and British governments, effectively allowed Hitler to annex the country's defensive frontier, leaving its industrial and economic core within a day's reach of the Wehrmacht. In reference to the Sudetenland and trenches being dug in a London central park, Chamberlain infamously declared in a September 1938 radio broadcast:

How horrible, fantastic it is that we should be digging trenches and trying on gas-masks here because of a quarrel in a far away country between people of whom we know nothing. I am myself a man of peace from the depths of my soul.

When Hitler invaded and seized the rest of Czechoslovakia in March 1939, Chamberlain felt betrayed by the breaking of the Munich Agreement and decided to take a much harder line against the Nazis, declaring war against Germany upon its invasion of Poland.

The repeated failures of the Baldwin government to deal with rising Nazi power are often historically laid on the doorstep of Chamberlain, since he presided over the final collapse of European affairs, resisted acting on military information, lied to the House of Commons about Nazi military strength, shunted out opposition which, correctly, warned of the need to prepare—and above all, failed to use the months profitably to ready for the oncoming conflict. However, it is also true that by the time of his premiership, dealing with the Nazi Party in Germany was an order of magnitude more difficult. Germany had begun general conscription previously, and had already amassed an air arm. Chamberlain, caught between the bleak finances of the Depression era and his own abhorrence of war—and a Kriegsherr who would not be denied a war—gave ground and entered history as a political scapegoat for what was a more general failure of political will and vision which had begun with the Treaty of Versailles in 1919.

It should be remembered that a policy of keeping the peace had broad support; had the Commons wanted a more aggressive prime minister, Winston Churchill would have been the obvious choice. Even after the outbreak of war, it was not clear that the invasion of Poland need lead to a general conflict. What convicted Chamberlain in the eyes of many commentators and historians was not the policy itself, but his manner of carrying it out and the failure to hedge his bets. Many of his contemporaries viewed him as stubborn and unwilling to accept criticism, an opinion backed up by his dismissal of cabinet ministers who disagreed with him on foreign policy. If accurate, this assessment of his personality would explain why Chamberlain strove to remain on friendly terms with the Third Reich long after many of his colleagues became convinced that Hitler could not be restrained.

Chamberlain believed passionately in peace, thinking it his job as Britain's leader to maintain stability in Europe; like many people in Britain and elsewhere, he thought that the best way to deal with Germany's belligerence was to treat it with kindness and meet its demands. He also believed that the leaders of men are essentially rational beings, and that Hitler must necessarily be rational as well. Most historians believe that Chamberlain, in holding to these views, pursued the policy of appeasement far longer than was justifiable, but it is not exactly clear whether any course could have averted war, and how much better the outcome would have been had armed hostilities begun earlier, given that France was unwilling to commit its forces, and there were no other effective allies: Italy had joined the Pact of Steel, the Soviet Union had signed a non-aggression pact, and the United States was still officially isolationist.

Chamberlain did, however, abort the proposal of von Kleist and Wilhelm Canaris before the invasion to Austria to eliminate Hitler, deciding to play on the edge of the situation: to maintain a strong anti-communist power in Central Europe, with the Nazis, accepting some “reward” on “lebensraum” and still “manage” with Hitler. His neglectful words for the people in Central Europe he practically offered to Hitler, and the Jews for that matter, constitute possibly the worst-ever diplomatic moment in British history. Chamberlain was nicknamed "Monsieur J'aime Berlin" (French for “Mr. I Love Berlin”) just before the outbreak of hostilities, and remained hopeful up until Germany's invasion of the Low Countries that a peace treaty to avert a general war could be obtained in return for concessions "that we don't really care about." This policy was widely-criticized at the time and since; however, given that the French General Staff was determined not to attack Germany but instead remain on the strategic defensive, what alternatives Chamberlain could have pursued were not clear. Instead, he used the months of the Phoney War to complete development of the Supermarine Spitfire and Hawker Hurricane fighter aircraft, and to strengthen the RDF or radar defense grid in England. Both of these priorities would pay crucial dividends in the Battle of Britain.

Outbreak of war

On September 1, 1939, Germany invaded Poland. Many in the United Kingdom expected war, but the government did not wish to make a formal declaration unless it had the support of France. France's intentions were unclear at that point, and the government could only give Germany an ultimatum: if Hitler withdrew his troops within two days, Britain would help to open talks between Germany and Poland. When Chamberlain announced this in the House on September 2, there was a massive outcry. The prominent Conservative former minister, Leo Amery, believing that Chamberlain had failed in his responsibilities, famously called on acting Leader of the Opposition Arthur Greenwood to "Speak for England, Arthur!" Chief Whip David Margesson told Chamberlain that he believed the government would fall if war was not declared. After bringing further pressure on the French, who agreed to parallel the British action, Britain declared war on September 3, 1939.

In Chamberlain's radio broadcast to the nation, he noted:

This morning the British Ambassador in Berlin handed the German Government a final note stating that, unless we heard from them by 11 o'clock that they were prepared at once to withdraw their troops from Poland, a state of war would exist between us. I have to tell you now that no such undertaking has been received, and that consequently this country is at war with Germany.

...Yet I cannot believe that there is anything more, or anything different, that I could have done, and that would have been more successful... Now may God bless you all and may He defend the right. For it is evil things that we shall be fighting against, brute force, bad faith, injustice, oppression, and persecution. And against them I am certain that the right will prevail.

As part of the preparations for conflict, Chamberlain asked all his ministers to "place their offices in his hands" so that he could carry out a full-scale reconstruction of the government. The most notable new recruits were Winston Churchill and former Cabinet Secretary Maurice Hankey. Much of the press had campaigned for Churchill's return to government for several months, and taking him aboard looked like a good way to strengthen the government, especially as both the Labour Party and Liberal Party declined to join.

Initially, Chamberlain intended to make Churchill a minister without portfolio (possibly with the sinecure office of Lord Privy Seal) and include him in a War Cabinet of just six members, with the service ministers outside it. However, he was advised that it would be unwise not to give Churchill a department, so Churchill instead became first lord of the admiralty. Chamberlain's inclusion of all three service ministers in the War Cabinet drew criticism from those who argued that a smaller cabinet of non-departmental ministers could take decisions more efficiently.

War premiership

The first eight months of the war are often described as the "Phoney War," for the relative lack of action. Throughout this period, the main conflict took place at sea, raising Churchill's stature; however, many conflicts arose behind the scenes.

The Soviet invasion of Poland and the subsequent Soviet-Finnish War led a call for military action against the Soviets, but Chamberlain believed that such action would only be possible if the war with Germany were concluded peacefully, a course of action he refused to countenance. The Moscow Peace Treaty in March 1940 brought no consequences in Britain, though the French government led by Édouard Daladier fell after a rebellion in the Chamber of Deputies. It was a worrying precedent for an allied prime minister.

Problems grew at the War Office as Secretary of State for War Leslie Hore-Belisha became an ever-more controversial figure. Hore-Belisha's high public profile and reputation as a radical reformer who was turning the army into a modern fighting force made him attractive to many, but he and the chief of the imperial general staff, Lord Gort, soon lost confidence in each other in strategic matters. Hore-Belisha had also proved a difficult member of the War Cabinet, and Chamberlain realized that a change was needed; the minister of information, Lord Macmillan, had also proved ineffective, and Chamberlain considered moving Hore-Belisha to that post. Senior colleagues raised the objection that a Jewish minister of information would not benefit relations with neutral countries, and Chamberlain offered Hore-Belisha the post of president of the board of trade instead. The latter refused and resigned from the government altogether; since the true nature of the disagreement could not be revealed to the public, it seemed that Chamberlain had folded under pressure from traditionalist, inefficient generals who disapproved of Hore-Belisha's changes.

When Germany invaded Norway in April 1940, an expeditionary force was sent to counter them, but the campaign proved difficult, and the force had to be withdrawn. The naval aspect of the campaign in particular proved controversial and was to have repercussions in Westminster.

Fall and resignation

Following the debacle of the British expedition to Norway, Chamberlain found himself under siege in the House of Commons. On May 8, over 40 government backbenchers voted against the government and many more abstained. Although the government won the vote, it became clear that Chamberlain would have to meet the charges brought against him. He initially tried to bolster his government by offering to appoint some prominent Conservative rebels and sacrifice some unpopular ministers, but demands for an all-party coalition government grew louder. Chamberlain set about investigating whether or not he could persuade the Labour Party to serve under him and, if not, then who should succeed him.

Two obvious successors emerged: Lord Halifax, then foreign minister, and Winston Churchill. Although almost everyone would have accepted Halifax, he was deeply reluctant to accept, arguing that it was impossible for a member of the House of Lords to lead an effective government. Over the next 24 hours, Chamberlain explored the situation further. Chamberlain was advised that if Labour declined to serve under Chamberlain, Churchill would have to try to form a government. Labour leaders Clement Attlee and Arthur Greenwood were unable to commit their party and agreed to put two questions to their National Executive Committee: Would they join an all-party government under Chamberlain? If not, would they join an all-party government under "someone else"?

The next day, Germany invaded the Netherlands, Belgium and France. At first, Chamberlain believed it was best for him to remain in office for the duration of the crisis, but opposition to his continued premiership was such that, at a meeting of the War Cabinet, Lord Privy Seal Sir Kingsley Wood told him clearly that it was time to form an all-party government. Soon afterwards, a response came from the Labour National Executive—they would not serve with Chamberlain, but they would with someone else. On the evening of 10 May 1940, Chamberlain tendered his resignation to the King and formally recommended Churchill as his successor.

Lord President of the Council and death

Despite his resignation as prime minister, Chamberlain remained leader of the Conservative Party and retained a great deal of support. Although Churchill was pressured by some of his own supporters and some Labour MPs to exclude Chamberlain from the government, he remembered the mistake that Lloyd George made in marginalizing Herbert Henry Asquith]] during the First World War and realized the importance of retaining the support of all parties in the Commons. Churchill had first planned to make Chamberlain chancellor of the exchequer and leader of the House of Commons, but so many Labour and Liberal leaders were reluctant to serve in such a government that Churchill instead appointed him as lord president of the council.

Chamberlain still wielded power within government as the head of the main home affairs committees, most notably the Lord President's Committee. He served loyally under Churchill, offering much constructive advice. Despite preconceived notions, many Labour ministers found him to be a helpful source of information and support. In late May 1940, the War Cabinet had a rapid series of meetings over proposals for peace from Germany which threatened to split the government. Churchill, supported by the Labour members Clement Attlee and Arthur Greenwood, was against the proposals, which were favored by Lord Halifax. Chamberlain was initially inclined to accept the terms, but this division threatened to bring down the government. Over the course of three days, Churchill, aided by Greenwood and the Liberal leader Sir Archibald Sinclair, gradually persuaded Chamberlain to oppose the terms, and Britain remained in the war.

At this stage, Chamberlain still retained the support of most Conservative MPs. This was most visible in the House of Commons, where Conservatives would cheer Chamberlain, while Churchill only received the applause of Labour and Liberal members. Realizing that this created the impression of a weak government, Chamberlain and the Chief Whip, David Margesson, took steps to encourage the formation of a Conservative power base that would support Churchill.

At first, Chamberlain and many others regarded Churchill as a mere caretaker premier and looked forward to a return to 10 Downing Street after the war. By midsummer, however, Chamberlain's health was deteriorating; in July he underwent an operation for stomach cancer. He made several efforts to recover, but by the end of September he felt that it was impossible to continue in government, and he formally resigned as both lord president and leader of the Conservative Party. By special consent of Churchill and the king, Chamberlain continued to receive state papers for his remaining months so that he could keep himself informed of the situation. He retired to Highfield Park, near Heckfield in Hampshire, where he died of cancer on November 9 at the age of 71, having lived for precisely six months after his resignation as premier.

Chamberlain's estate was probated at 84,013 pounds sterling on April 15, 1941.

Legacy

Chamberlain's legacy remains controversial. His policy on Europe has dominated most writings to such an extent that many histories and biographies devote almost all coverage of his premiership to this single area of policy.

Written criticism of Chamberlain was given its first early boost in the 1940 polemic Guilty Men, which offered a deeply critical view of the politics of the 1930s, most notably the Munich Agreement and steps taken towards rearmament. Together with Churchill's post-war memoirs The Second World War, texts like Guilty Men heavily condemned and vilified appeasement. The post-war Conservative leadership was dominated by individuals such as Churchill, Eden, and Harold Macmillan, who had made their names opposing Chamberlain. Some even argued that Chamberlain's foreign policy was in stark contrast to the traditional Conservative line of interventionism and a willingness to take military action.

In recent years, a revisionist school of history has emerged to challenge many assumptions about appeasement, arguing that it was a reasonable policy given the limitations of British arms available, and the scattering of British forces across the world, and the reluctance of dominion governments to go to war. Some have also argued that Chamberlain's policy was entirely in keeping with the Conservative tradition started by Lord Derby between 1846 and 1868 and followed in the Splendid Isolation under Lord Salisbury in the 1880s and 1890s. The production of aircraft was greatly increased at the time of the Munich Agreement. Had war begun instead, the Battle of Britain may have had a much different dynamic with biplanes instead of advanced Spitfires meeting the Germans. More likely, however, German aircraft would have been fully engaged against France and Czechoslovakia. Against the argument that Hitler could neither be trusted nor appeased, it can be stated that diplomacy should always be explored and given a chance before armed conflict.

The emphasis on foreign policy has overshadowed Chamberlain's achievements in other spheres. His achievements as minister of health have been much praised by social historians, who have argued that he did much to improve conditions and brought the United Kingdom closer to the Welfare State of the post-war world.

A generally unrecognized aspect of Chamberlain is his role in the inception of and drawing up of a remit for the Special Operations Executive.[2] This was empowered to use sabotage and subterfuge to defeat the enemy. His eagerness to avoid another Great War was matched by the ferocity of the SOE charter, which he drew up.

Chamberlain was, to an extent, unfortunate in his biography; when his widow commissioned Keith Feiling to write an official life in the 1940s, the government papers were not available for consultation. As a result, Feiling was unable to tackle criticisms by pointing to the government records in a way that later biographers could. Feiling filled the gap with extensive use of Chamberlain's private papers and produced a book that many consider to be the best account of Chamberlain's life, but which was unable to overcome the negative image of him at the time. Later historians have done much more, both emphasizing Chamberlain's achievements in other spheres and making strong arguments in support of appeasement as the natural policy, but a new clear consensus has yet to be reached. Lacking the charisma and flamboyance of his successor, he has tended to stand in Churchill's shadow.

Notes

- ↑ Chamberlain went to his formal appointment at Buckingham Palace uncertain about whether or not the term "kiss hands" was literal or metaphorical. The staff at the palace whom he spoke to before meeting the king did not know either. It was only when the king invited him to sit down, without offering a hand, that Chamberlain deduced the answer.

- ↑ Foreign and Commonwealth Office, Part 1: The Special Operations Executive and its Records. Retrieved July 30, 2007.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Chamberlain, Neville. Norman Chamberlain: A Memoir. London: John Murray, 1923.

- Chamberlain, Neville. In Search of Peace: Speeches (1937-1938). London: National Book Association, Hutchinson & Co. (Publishers) Ltd., 1938.

- Chamberlain, Neville. The Struggle for Peace. London: Hutchinson, 1939.

Biographies:

- Dilks, David. Neville Chamberlain. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1984. ISBN 9780521257244

- Dutton, David. Neville Chamberlain. London: Arnold, 2001. ISBN 9781417532063

- Feiling, Keith. The Life of Neville Chamberlain. London: Macmillan & Co. Ltd, 1946.

- Gilbert, Martin. The Roots of Appeasement. New York: New American Library, 1966.

- James, Robert Rhodes. The British Revolution, 1880-1939. New York: Knopf, 1977. ISBN 978-0394407616

- Matthew, H. C. G. and Brian Harrison (eds.). The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004. ISBN 978-0198614111

- Wheeler-Bennett, John. Munich: Prologue to Tragedy. New York: Duell, Sloan and Pearce, 1948.

External Links

All links retrieved November 11, 2022.

- Historic Figures: Neville Chamberlain – BBC

- Neville Chamberlain – Encyclopaedia Britannica

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.