New Economic Policy

The New Economic Policy (NEP) (Russian: новая экономическая политика (НЭП), tr. novaya ekonomicheskaya politika) was an economic policy of the Soviet Union proposed by Vladimir Lenin in 1921 to address the economic challenges brought on by the Russian Civil War (1919-1922) and the failures of the policy of War Communism (1918-1921).

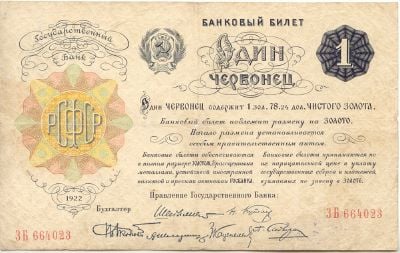

The NEP represented a more market-oriented economic policy to foster economic growth in a country which had suffered severely due to war and revolution since 1915. The Bolshevik government adopted the NEP in the course of the 10th Congress of the All-Russian Communist Party (March 1921) and promulgated it by a decree on March 21, 1921: "On the Replacement of Prodrazvyorstka by Prodnalog". Further decrees refined the policy. Other policies included monetary reform (1922–1924) and the attraction of foreign capital.

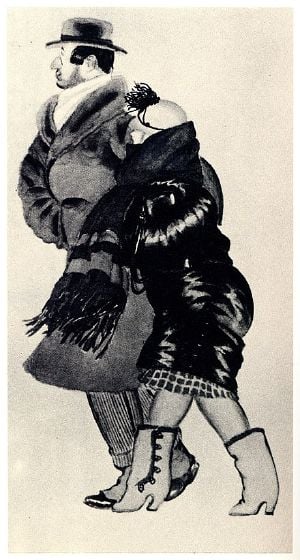

The NEP created a new category of people called NEPmen (нэпманы) (nouveau riches). Joseph Stalin abandoned the NEP in 1928 with the Great Break, his policy of forced collectivization of agriculture and rapid industrialization.

Background

In November 1917, the Bolsheviks seized control from the provisional government. There were immediate economic and political challenges. Karl Marx had predicted the communist revolution would take place in a capitalist country, but Russia was still largely agrarian and peasant. There was also an immediate political backlash. The Russian Civil War of 1917–1922 pitted the Bolsheviks and their allies against the Whites and other counter-revolutionary forces. During this period the Bolsheviks attempted to administer Russia's economy, still largely agrarian with only a nascent capitalist sector purely by decree, a policy known as War Communism. Food was seized from farmers. Factory workers were ordered to produce, and goods were seized by decree.[1] While this policy enabled the Bolshevik regime to overcome shortages initially, it soon caused economic disruptions and hardships.

Combined with the devastation of the war, these were major hardships for the Russian people and diminished popular support for the Bolsheviks. Peasants, because of the extreme scarcity, began to refuse to co-operate in giving food for the war effort. Producers who were not directly compensated for their labor often stopped working, leading to widespread shortages. As food became more scarce for urban workers, some migrated from the cities to the countryside, where the chances to feed themselves were higher. It reduced the opportunity for the barter of industrial goods for food and worsened the situation of the remaining urban population, weakening the economy and industrial production. Between 1918 and 1920, Petrograd lost 70 percent of its population, while Moscow lost over 50 percent.[2]

At the end of the Civil War, the Bolsheviks controlled Russian cities, but 80 percent of the Russian population were peasants:

... the writ of centralized state power did not extend much beyond the cities and the (partially destroyed) rail lines connecting them. In the broad expanses of the countryside, peasants, who comprised upwards of 80 percent of the total population, hunkered down in their communes, having both economically and psychologically withdrawn from the state and its military and food detachments.[3]

While almost all the fighting in the Civil War occurred outside urban areas, urban populations decreased substantially.[4] The war disrupted transportation (especially railroads), and basic public services. Infectious diseases thrived, especially typhus. Shipments of food and fuel by railroad and by water dramatically decreased. City residents first experienced a shortage of heating oil, then coal, leaving them to resort to burning wood for heat. Populations in northern towns (excluding capital cities) declined an average of 24 percent.[5] Northern towns were impacted the most, receiving less food than towns in the agricultural south. Petrograd alone lost 850,000 people, half of the urban population decline during the Civil War.[5] Hunger and poor conditions drove residents out of cities. Workers migrated south to get peasants' surpluses. Those migrants who had more recently gone to the cities for work left because they still had ties to villages.[4]

Urban workers formed the core of Bolshevik support, so the exodus posed a serious problem. Factory production severely slowed or halted. Factories lost 30,000 workers in 1919. To survive, city dwellers sold personal valuables, made artisan craft-goods for sale or barter, and planted gardens. The acute need for food drove them to obtain 50–60 percent of food through illegal trading by meshochniks (bag people). The shortage of cash caused the black market to use a barter system, which was inefficient.[6] Drought and frost led to the Russian famine of 1921, in which millions starved to death, especially in the Volga region, further eroding urban support for the Bolshevik party.[7] When no bread arrived in Moscow in 1921, workers became hungry and disillusioned. They organized demonstrations against the Bolshevik Party's policy of privileged rations, in which the Red Army, Party members, and students received rations first. The Kronstadt rebellion of soldiers and sailors, who had been supporters of the Bolsheviks, broke out in March 1921, fueled by anarchism and populism.[6] In 1921 Lenin replaced the food requisitioning policy with a tax, signaling the inauguration of the New Economic Policy.[8]

Policies

Lenin characterized the NEP in 1922 as an economic system that would include "a free market and capitalism, both subject to state control," while socialized state enterprises would operate on "a profit basis."[9]

The NEP represented a move away from full nationalization of certain parts of industries. The new laws sanctioned the co-existence of private and public sectors, creating a state oriented "mixed economy."[10] The policy partially revoked the complete nationalization of industry (established during the period of War Communism, introducing a mixed economy which allowed private individuals to own small and medium sized enterprises,[11] while the state continued to control large industries, banks and foreign trade.[12] In addition, the NEP abolished prodrazvyorstka (forced grain-requisition)[11] introducing prodnalog: a tax on farmers in its place, payable in the form of raw agricultural product.[13]

The goals of the Soviets were several. They expected it would generate foreign investments which were needed in order to fund industrial and developmental projects with foreign exchange or technology requirements.[14] For industrial development, they required a steady supply of food for industrial workers. War Communism had not worked. The NEP instituted a revision of their agricultural policy.[15] The Bolsheviks viewed traditional village life as conservative and backward, but efforts at collectivization to this point were still met with great resistance. Given their dire economic situation after the civil war, NEP allowed the state to cultivate better relations with the peasants, allowing private landholdings because the idea of collectivized farming had met such strong opposition.[16]

Capitalist incentive

Lenin, faced with dire economic conditions, turned to capitalist incentive to boost production. He opened up markets to permit a greater degree of free trade, hoping to motivate the population to increase production. Under NEP, not only were "private property, private enterprise, and private profit largely restored in Lenin's Russia," but Lenin's regime turned to international capitalism for assistance, willing to provide "generous concessions to foreign capitalism." Lenin took the position that in order to achieve socialism, he had to create "the missing material prerequisites" of modernization and industrial development that Russia had lacked prior to the revolution. That made it imperative for Soviet Russia to "fall back on a centrally supervised market-influenced program of state capitalism." Lenin was following Karl Marx's precepts that a nation must first reach "full maturation of capitalism as the precondition for socialist realization." Future years would use the term Marxism–Leninism to describe Lenin's approach to economic policies, which were seen to favor policies that moved the country toward communism.[17] The main policy Lenin used was an end to grain requisitions. Instead he allowed the peasants to keep and trade part of their produce, instituting a tax on their profits. At first, this tax was paid in kind, but as the currency became more stable in 1924, it was changed to a cash payment.[11] This increased the peasants' incentive to produce, and in response production jumped by 40 percent after the drought and famine of 1921–1922.[18]

NEP economic reforms aimed to take a step back from central planning to allow the economy to become more independent. NEP labor reforms tied labor to productivity, incentivizing the reduction of costs and the redoubling the efforts of labor. Labor unions became independent civic organizations.[11] NEP reforms also opened up government positions to the most qualified workers. The NEP gave opportunities for the government to use engineers, specialists, and intelligentsia for cost accounting, equipment purchasing, efficiency procedures, railway construction, and industrial administration. A new class of "NEPmen" thrived. These private traders opened up urban firms hiring up to 20 workers. NEPmen also included rural artisan craftsmen selling their wares on the private market.[19]

Policy Impact

After the New Economic Policy was instituted, agricultural production increased greatly. In order to stimulate economic growth, farmers were given the opportunity to sell portions of their crops to the government in exchange for monetary compensation. Farmers now had the option to sell some of their produce, giving them a personal economic incentive to produce more grain.[16] This incentive, coupled with the breakup of the quasi-feudal landed estates, surpassed pre-Revolution agricultural production. The agricultural sector became increasingly reliant on small family farms, while heavy industries, banks, and financial institutions remained owned and run by the state. This created an imbalance in the economy as the agricultural sector grew much faster than heavy industry. To maintain their income, factories raised prices. Due to the rising cost of manufactured goods, peasants had to produce much more wheat to buy these consumer goods, which increased supply and thus lowered the price of their agricultural products. This fall in prices of agricultural goods and sharp rise in prices of industrial products was known as the Scissors Crisis (due to the crossing of graphs of the prices of the two types of product). Peasants began withholding their surpluses in wait for higher prices, or sold them to "NEPmen" (traders and middle-men) who re-sold them at high prices. Many Communist Party members considered this an exploitation of urban consumers. To lower the price of consumer goods, the state took measures to decrease inflation and enact reforms on the internal practices of the factories. The government also fixed prices, in an attempt to halt the scissor effect.[20]

Backlash

Lenin and his followers saw the NEP as an interim measure, a strategic retreat from socialism. He understood it was capitalism, but justified it by insisting that it was a different type of capitalism, "state capitalism", the last stage of capitalism before the evolution to socialism .[16] However, it proved highly unpopular with the Left Opposition in the Bolshevik Party because of its compromise with some capitalist elements and the relinquishment of state control.[13] The Left saw the NEP as a betrayal of Communist principles, and believed it would have a negative long-term economic effect. They stood for a fully planned economy instead. In particular, the NEP fostered a class of traders ("NEPmen") whom the Communists regarded as "class enemies" of the working class. Vladimir Lenin is quoted to have said "For a year we have been retreating. On behalf of the Party we must now call a halt. The purpose pursued by the retreat has been achieved. This period is drawing, or has drawn, to a close."[21] Lenin had also been known to say about NEP, "We are taking one step backward, to take two steps forward later."[22] NEP was intended to provide the economic conditions necessary for socialism eventually to evolve.

Stalin was initially receptive towards Lenin's shift in policy towards a state capitalist system. By 1923, the last year of Lenin's life, he argued in the Twelfth Party Congress in April 1923 that it allowed the "growth of nationalistic and reactionary thinking..." He also expressed that in the recent Central Committee plenum there were speeches made which were incompatible with communism, all of which were ultimately caused by the NEP. These statements were made just after Lenin was incapacitated by stroke.[23]

With Lenin incapacitated (he would die in January 1924), Leon Trotsky and Joseph Stalin tangled over how to develop the Soviet economy. It was part of a struggle for power. Trotsky, who promulgated a policy of Permanent revolution was supported by radical members of the Communist Party, the so-called Left Opposition. Its most prominent members were Trotsky, Grigory Zinoviev and Lev Kamenev. They believed that socialism in Russia would only survive if the state controlled the allocation of all output. Trotsky believed that the state should repossess all output to invest in capital formation. Despite his stated concerns, Stalin initially supported NEP and the more moderate members of the Communist Party. He advocated for a state-run capitalist economy, at least until he managed to wrest control of the Communist Party from Trotsky. After defeating the Trotsky faction, Stalin reversed his opinions about economic policy and implemented the first five-year plan, turning on his erstwhile supporters, Nikolai Bukharin and Karl Radek.[24]

End of NEP

By 1924, after Lenin's death in January, Nikolai Bukharin had become the foremost supporter of the New Economic Policy. The power struggle between Stalin and the Left Opposition played out over the succeeding three year period. By 1927, Stalin, with the help of Bukharin, Karl Radek, and Mikhail Tomsky, successfully routed the Left Opposition. Having secured his left flank, he turned against Bukharin and what would come to be called the Right Opposition.

The USSR abandoned NEP in 1928 after Joseph Stalin worked his way into a position of leadership during the Great Break, a period of both economic and political centralization and cultural revolution. The term came from the title of Joseph Stalin's article "Year of the Great Turn" ("Год великого перелома: к XII годовщине Октября", literally: "Year of the Great Break: Toward the 12th Anniversary of October") published on November 7, 1929, the 12th anniversary of the October Revolution.[25] While NEP had successfully stabilized the Soviet economy, Stalin wanted to embark on a vast industrialization program. Having eliminated the Left Opposition, he turned against Bukharin and the NEP policy and embraced the position of the Left Opposition that NEP was not sufficiently communist. He considered peasant farms too small to support the massive agricultural demands of the Soviet Union's push for rapid industrialization. The Grain Procurement Crisis of 1928, during which grain procurement proved to be inadequate to the needs of urban workers, would prove to be fatal for NEP.

In order to ensure adequate food supply for urban workers, Stalin enacted a system of collectivization.[26] In order to accumulate capital for rapid industrialization, he introduced the Five Year Plans starting in 1928. It would officially bring NEP to a close. After seven years of NEP, Stalin introduced full central planning, re-nationalizing much of the economy, and from the late 1920s onwards introduced a policy of rapid industrialization and collectivization of agriculture.

Legacy

The NEP succeeded in creating an economic recovery after the devastation of World War I, the October Revolution, and the Russian Civil War. By 1925, in the wake of Lenin's NEP, a "... major transformation was occurring politically, economically, culturally and spiritually." Small-scale and light industries were largely in the hands of private entrepreneurs or cooperatives. By 1928, agricultural and industrial production had been restored to the 1913 (pre-World War I) level.[13]

Rejection of NEP

The Bolsheviks hoped that the USSR's industrial base would reach the level of capitalist countries in the West, to avoid losing a future war. (Stalin proclaimed, "Either we do it, or we shall be crushed.") For that purpose he believed NEP would not provide the basis for his program of rapid industrialization. Stalin tried to rally the support of peasants for collectivization by giving them an enemy to blame for their difficulties. He asserted that the grain crisis was caused by kulaks – peasants who had fared better after the Emancipation of the Serfs 1861. The kulaks were farmers who were relatively better off compared to other members of the commune. Stalin accused them of "hoarding" grain and "speculation of agricultural produce" in an effort to create class conflict. Stalin imposed collectivization of agriculture by seizing land held by the kulaks. It was given to agricultural cooperatives (kolkhozes and sovkhozes).[27] The collectivization policy was less than successful economically, leading to mass famines and the deaths of millions.

Impact on China

Pantsov and Levine see many of the post-Mao economic reforms of the Chinese Communist Party's former paramount leader Deng Xiaoping away from a command economy and towards a "socialist market economy" during the 1980s as influenced by the NEP:

It will be recalled that Deng Xiaoping himself had studied Marxism from the works of the Bolshevik leaders who had propounded NEP. He drew on ideas from NEP when he spoke of his own reforms. In 1985, he openly acknowledged that 'perhaps' the most correct model of socialism was the New Economic Policy of the USSR.[28]

Notes

- ↑ Jennifer Llewellyn, Michael McConnell, and Steve Thompson, "The New Economic Policy (NEP)," Alpha History, June 18, 2019. Retrieved January 12, 2023.

- ↑ Richard Pipes, Russia Under the Bolshevik Regime (New York, NY: Knopf Doubleday, 2011, ISBN 978-0307788610), 371. Retrieved January 22, 2023.

- ↑ Lewis H. Siegelbaum, Soviet State and Society Between Revolutions, 1918–1929 Cambridge Russian Paperbacks, Volume 8 (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1992, ISBN 978-0521369879), 68.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Diane P. Koenker, William G. Rosenberg, and Ronald Grigor Suny, (eds.), Party, State, and Society in the Russian Civil War: Explorations in Social History (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1989, ISBN 978-0253205414), 58–80.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Koenker, Rosenberg, and Suny, 61.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Koenker, Rosenberg, and Suny, 58–119.

- ↑ Peter Kenez, A History of the Soviet Union from the Beginning to the End (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2006, ISBN 978-0521682961), 48. Retrieved January 22, 2023.

- ↑ Siegelbaum, 85.

- ↑ V. I. Lenin, "The Role and Functions of the Trade Unions under the New Economic Policy," in Lenin's Collected Works, 2nd edition, ed. and trans. David Skvirsky and George Hanna, Volume 33, 184., Progress Publishers, Moscow, 1973. Retrieved January 22, 2023.

- ↑ V N. Bandera, "New Economic Policy (NEP) as an Economic Policy," Journal of Political Economy 71(3) (1963): 268. Retrieved January 22, 2023.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 Peter Kenez, A History of the Soviet Union from the Beginning to the End (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2006, ISBN 978-0521682961), 47–48. Retrieved January 22, 2023.

- ↑ Elisabeth Gaynor Ellis and Anthony Esler, World History; The Modern Era (Boston, MA: Pearson Prentice Hall, 2007, ISBN 978-0131299733), 483.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 Robert Service, A History of Twentieth-Century Russia (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1997, ISBN 0674403487), 124-125.

- ↑ Sheila Fitzpatrick, The Russian Revolution 4th ed. (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2017, ISBN 978-0198806707), 96.

- ↑ Vladimir P. Timoshenko, Agricultural Russia and the Wheat Problem (Stanford, CA: Food Research Institute, Stanford University Press, 1932), 86.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 Sheldon Richman, "War Communism to NEP: the road from serfdom," Journal of Libertarian Studies (1981): 93–94. Retrieved January 22, 2023.

- ↑ Raymond E. Zickel, Soviet Union a Country Study, 2nd ed. (Washington, DC: Library of Congress, Federal Research Division, 1991, ISBN 978-0844407272), 64. Retrieved January 22, 2023.

- ↑ Siegelbaum, 90.

- ↑ Siegelbaum, 97–116.

- ↑ Bandera, 265–279.

- ↑ "Eleventh Congress of the R.C.P.(B.)," marxists.org, March 27-April 2, 1922. Retrieved January 22, 2023.

- ↑ Orlando Figes, Revolutionary Russia, 1891–1991: A History (New York, NY: Metropolitan Books, 2014, ISBN 978-0805091311).

- ↑ Robert Himmer, "The Transition from War Communism to the New Economic Policy: An Analysis of Stalin's Views," Russian Review 53(4) (October 1994): 515–529.

- ↑ Fitzpatrick, 115.

- ↑ Lynne Viola, Peasant rebels under Stalin: Collectivization and the Culture of Peasant Resistance (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 1996, ISBN 978-0195101973).

- ↑ Collectivization would, in fact, trigger a famine that killed millions as peasants resisted the policy.

- ↑ Donald Kagan, The Western Heritage (London, UK: Pearson Prentice Hall, 2010, ISBN 978-0205705177).

- ↑ Alexander Pantsov and Steven I. Levine, Deng Xiaoping: A Revolutionary Life (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2015, ISBN 9780199392032), 373. Retrieved January 22, 2023.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Bandera, V. N. "New Economic Policy (NEP) as an Economic Policy," Journal of Political Economy 71(3) (1963): 265-279. Retrieved January 22, 2023.

- Ellis, Elisabeth Gaynor, and Anthony Esler. World History; The Modern Era. Boston, MA: Pearson Prentice Hall, 2007. ISBN 978-0131299733

- Figes, Orlando. Revolutionary Russia, 1891–1991: A History. New York, NY: Metropolitan Books, 2014. ISBN 978-0805091311

- Fitzpatrick, Sheila. The Russian Revolution 4th ed. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2017. ISBN 978-0198806707

- Himmer, Robert. "The Transition from War Communism to the New Economic Policy: An Analysis of Stalin's Views," Russian Review 53(4) (October 1994): 515–529.

- Kagan, Donald. The Western Heritage. London, UK: Pearson Prentice Hall, 2010. ISBN 978-0205705177

- Kenez, Peter. A History of the Soviet Union from the Beginning to the End. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2006. ISBN 978-0521682961

- Koenker, Diane P., William G. Rosenberg, and Ronald Grigor Suny (eds.), Party, State, and Society in the Russian Civil War: Explorations in Social History. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1989. ISBN 978-0253205414

- Lenin, V. I., "The Role and Functions of the Trade Unions under the New Economic Policy," in Lenin's Collected Works, 2nd edition, ed. and trans. David Skvirsky and George Hanna, Volume 33, 176-186, Progress Publishers, Moscow, 1973.

- Llewellyn, Jennifer, Michael McConnell, and Steve Thompson. "The New Economic Policy (NEP)," Alpha History, June 18, 2019. Retrieved January 12, 2023.

- Pantsov, Alexander, and Levine, Steven I. Deng Xiaoping: A Revolutionary Life. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2015; ISBN 9780199392032

- Pipes, Richard. Russia Under the Bolshevik Regime. New York, NY: Knopf Doubleday, 2011. ISBN 978-0307788610

- Richman, Sheldon L. "War Communism to NEP: The Road from Serfdom," The Journal of Libertarian Studies V no. 1, 1981.

- Service, Robert. A History of Twentieth-Century Russia. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1997. ISBN 0674403487

- Siegelbaum, Lewis H. Soviet State and Society Between Revolutions, 1918–1929. Cambridge Russian Paperbacks, Volume 8. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1992. ISBN 978-0521369879

- Timoshenko, Vladimir P. Agricultural Russia and the Wheat Problem. Stanford, CA: Food Research Institute, Stanford University Press, 1932.

- Viola, Lynne. Peasant rebels under Stalin : Collectivization and the Culture of Peasant Resistance. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 1996. ISBN 978-0195101973

- Zickel, Raymond E. Soviet Union a Country Study, 2nd ed. Washington, DC: Library of Congress, Federal Research Division, 1991. ISBN 978-0844407272

Further reading

- Ball, Alan M. Russia's Last Capitalists: The NEPmen, 1921–1929. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1987. ISBN 978-0520057173

- Davies, R. W. (ed.). From Tsarism to the New Economic Policy: Continuity and Change in the Economy of the USSR. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1991. ISBN 978-0801499197

- Fitzpatrick, Sheila, et al. (ed.). Russia in the Era of NEP: Explorations in Soviet Society and Culture. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1991. ISBN 978-0253206572

- Nenovsky, Nikolay, "Lenin and the Currency Competition: Reflections on the NEP Experience (1922–1924)". Turin, Italy: International Center of Economic Research Working Paper No. 22, 2006. Retrieved January 22, 2023.

External links

Links retrieved January 19, 2023.

- The New Economic Policy And The Tasks Of The Political Education Departments V.I Lenin 17 Oct. 1921.

- Role and Functions of the Trade Unions Under The New Economic Policy V. I. Lenin. 12 Jan 1922.

- Sahoboss. "The Impact of Lenin and Stalin's Policies on the Rights of the Russian People." South African History Online, 8 May 2017.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.