NirvÄá¹a (Pali: NibbÄna, meaning "extinction" or "blowing out" of the triple fires of greed, anger, and delusion), is the highest goal of Theravada Buddhism, understood to be the end of suffering (dukkha). The Buddha described nirvana as the unconditioned mode of being that is free from mind-contaminants (kilesa) such as lust, anger, or craving. It is the highest spiritual attainment, which dissolves the causes for future becoming (Karma) that keep beings forever wandering through realms of desire and form (samsara).

There are many synonyms for nirvana, as shown by the following passage from the Samyutta Nikaya (a scripture of Buddhism), which describes nirvana as:

- â¦the far shore, the subtle, the very difficult to see, the unaging, the stable, the undisintegrating, the unmanifest, the unproliferated, the peaceful, the deathless, the sublime, the auspicious, the secure, the destruction of craving, the wonderful, the amazing, the unailing, the unailing state, the unafflicted, dispassion, purity, freedom, the unadhesive, the island, the shelter, the asylum, the refuge⦠(SN 43:14)

The concept of nirvana remains an important ideal and aspiration for millions of Buddhists around the world.

Descriptions

Traditionally, definitions of nirvana have been provided by saying what it is not, thus pointing to nirvana's ineffable nature. The Buddha discouraged certain lines of speculation, including speculation into the state of an enlightened being after death, on the grounds that such questions were not useful for pursuing enlightenment; thus definitions of nirvana might be said to be doctrinally unimportant in Buddhism.

Approaching nirvana from the angle of the via negativa, the Buddha calls nirvÄna "the unconditioned element" (i.e., not subject to causation). It is also the "cessation of becoming" (bhavanirodha nibbÄnam) (SN-Att. 2.123). Nirvana is also never conceived of as a place, but the antinomy of samsÄra, which itself is synonymous with ignorance (avidyÄ; PÄli: avijjÄ). Additionally, nirvana is not the clinging existence with which humanity is said to be afflicted. It has no origin or end. It is not made or fabricated. It has no dualities, so that it cannot be described in words. It has no parts that may be distinguished one from another. It is not a subjective state of consciousness. It is not conditioned on or by anything else. Doctrinally, "'the liberated mind (citta) that no longer clingsâ means NibbÄna [Nirvana]â (Majjhima Nikaya 2-Att. 4.68).

Positively speaking, nirvana carries connotations of stilling, cooling, and peace. The realizing of nirvana is compared to the ending of avidyÄ (ignorance) which perpetuates the will into effecting the incarnation of mind into biological or other form, passing on forever through life after life (samsara). Samsara is caused principally by craving and ignorance (see dependent origination). Nirvana, then, is not a place nor a state; it is an absolute truth to be realized.

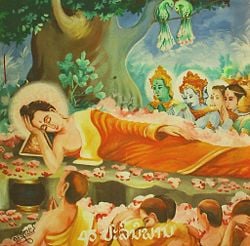

Parinirvana

In Buddhism, parinirvana (meaning "complete extinction") is the final nirvana, usually understood to be within reach only upon the death of the body of someone who has attained complete awakening (bodhi). It is the ultimate goal of Buddhist practice and implies a release from the cycle of deaths and rebirths as well as the dissolution of all worldly physical and mental aggregates known as skandhas (form, feeling, perception, mental fabrications, and consciousness). When a person who has realized nirvana dies, his or her death is referred as parinirvana (fully passing away) and it is said that the person will not be reborn again. Buddhism holds that the ultimate goal and end of samsaric existence (of ever "becoming" and "dying" and never truly being) is realization of nirvana; what happens to a person after his parinirvana cannot be explained, as it is outside of all conceivable experience.

The Buddhist term Mahaparinirvana, meaning "great, complete Nirvana," refers to the ultimate state of nirvana (everlasting, highest peace and happiness) entered by an Awakened Being (Buddha) or "arhat" (Pali: arahant) at the moment of physical death, when the mundane skandhas (constituent elements of the ordinary body and mind) are shed and only the Buddhic skandhas remain. However, it can also refer (in the Mahayana) to the same inner spiritual state reached during a Buddha's physical lifetime. In the Mahayana Buddhist scripture entitled the "Mahayana Mahaparinirvana Sutra," the Buddha teaches that unlike "ordinary" nirvana, "Mahaparinirvana" is the highest state or realm realized by a perfect Buddha, a state in which that Buddhic being awakens to "the Eternal, Bliss, the Self, and the Pure." Only in Mahaparinirvana is this True Self of the Buddha said to be fully discernible. One can understand the relationship between nirvana and samsara in terms of the Buddha while on earth. Buddha was both in samsara while having attained to nirvana so that he was seen by all, and simultaneously free from samsara.

Nirvana in Buddhist commentaries

A Buddhist Sarvastivà din commentary, Abhidharma-mahavibhà sa-sà stra, provides a careful analysis of the possible etymological meanings of nirvana that are derived from its Sanskrit roots:

- VÃ na, implying the path of rebirth, + nir, meaning "leaving off" or "being away from the path of rebirth."

- VÃ na, meaning "stench," + nir, meaning "freedom": "Freedom from the stench of distressing kamma."

- Và na, meaning "dense forests," + nir, meaning "to get rid of" = "to be permanently rid of the dense forest of the five aggregates (panca skandha)," or the "three roots of greed, hate, and delusion (lobha, dosa, moha)" or the "three characteristics of existence" (impermanence, anitya; unsatisfactoriness, dukkha; soullessness, anà tma).

- VÃ na, meaning "weaving," + nir, meaning "knot" = "freedom from the knot of the distressful thread of kamma."

Mahayana perspectives

In MahÄyÄna Buddhism, calling nirvana the "opposite" of samsÄra or implying that it is separate from samsÄra is doctrinally problematic. According to early MahÄyÄna Buddhism, nirvana and samsara can be considered to be two aspects of the same perceived reality. By the time of NÄgÄrjuna (second century C.E.), the identity of nirvana and samsÄra are alleged.

The TheravÄda school makes the dichotomy of samsÄra and NibbÄna the starting point of the entire quest for deliverance. Even more, it treats this antithesis as determinative of the final goal, which is precisely the transcendence of samsara and the attainment of liberation in NibbÄna. Where Theravada differs significantly from the MahÄyÄna schools, which also start with the duality of samsÄra and nirvana, is in not regarding this polarity as a mere preparatory lesson tailored for those with blunt faculties, to be eventually superseded by some higher realization of non-duality. From the standpoint of the PÄli Suttas, even for the Buddha and the Arahants, suffering and its cessation, samsÄra and NibbÄna, remain distinct.

The MahÄparinirvÄna SÅ«tra

The nature of nirvana is discussed in what alleges to be the final of all Mahayana sutras, allegedly delivered by the Buddha on his last day of life on earthâthe Mahaparinirvana Sutra or Nirvana Sutra. Here, as well as in a number of linked Tathagatagarbha sutras, in which the Tathagatagarbha is equated with the Buddha's eternal Self or eternal nature, nirvana is spoken of by the Mahayana Buddha in very "cataphatic," positive terms. Nirvana, or "Great NirvÄna," is indicated to be the sphere or domain (vishaya) of the True Self. It is seen as the state that constitutes the attainment of what is "Eternal, the Self, Bliss, and the Pure." MahÄ-nirvÄna ("Great Nirvana") thus becomes equivalent to the ineffable, unshakeable, blissful, all-pervading, and deathless Selfhood of the Buddha himselfâa mystery which no words can adequately reach and which, according to the Nirvana Sutra, can only be fully known by an Awakened Beingâa perfect Buddhaâdirectly.

Strikingly, the Buddha of the Mahaparinirvana Sutra gives the following definition of the attributes of nirvana, which includes the ultimate reality of the Self (not to be confused with the "worldly ego" of the five skandhas):

- The attributes of Nirvana are eightfold. What are these eight? Cessation [nirodha], loveliness/ wholesomeness [subha], Truth [satya], Reality [tattva], eternity [nitya], bliss [sukha], the Self [atman], and complete purity [parisuddhi]: that is Nirvana.

He further states: "Non-Self is Samsara [the cycle of rebirth]; the Self (atman) is Great Nirvana."

Here the Buddha of the MahÄparinirvÄna SÅ«tra insists on its eternal nature and affirms its identity with the enduring, blissful Self, saying:

- It is not the case that the inherent nature of NirvÄna did not primordially exist but now exists. If the inherent nature of NirvÄna did not primordially exist but does now exist, then it would not be free from taints (Äsravas) nor would it be eternally (nitya) present in nature. Regardless of whether there are Buddhas or not, its intrinsic nature and attributes are eternally present⦠Because of the obscuring darkness of the mental afflictions (kleÅas), beings do not see it. The TathÄgata, endowed with omniscient awareness (sarvajñÄ-jñÄna), lights the lamp of insight with his skill-in-means (upÄya-kauÅalya) and causes Bodhisattvas to perceive the Eternal, Bliss, the Self, and the Pure of NirvÄna.

According to these MahÄyÄna teachings, any being who has reached nirvana is not blotted out or extinguished: There is the extinction of the impermanent and suffering-prone "worldly self" or ego (comprised of the five changeful skandhas), but not of the immortal "supramundane" Self of the indwelling Buddha Principle (Buddha-dhatu). Spiritual death for such a being becomes an utter impossibility. The Buddha states in the MahÄyÄna MahÄparinirvÄna Sutra (Tibetan version): "NirvÄna is deathless⦠Those who have passed into NirvÄna are deathless. I say that anybody who is endowed with careful assiduity is not compounded and, even though they involve themselves in compounded things, they do not age, they do not die, they do not perish."

Misconceptions

There are many misconceptions surrounding the Buddhist concept of nirvana, which derive from Buddhism's connection to Hinduism. Metaphysically, it should be noted that nirvana is not considered to be the same as the Hindu concept of moksha. Though the two concepts may appear to be similar because each refers to an escape from samsaric suffering, they, nevertheless, are still based on different metaphysical presuppositions and are incomensurate.

In the Saamannaphala Sutta of the Digha Nikaya, the Buddha clearly outlines the differences between his teaching of nirvana and the Hindu schools' teaching, which are considered to be wrong views. The Buddha emphasized that the Hindu belief in a permanent self (atman) not only negates the activities of moral life but also falls in a form of grasping, a hindrance to spiritual liberation.[1]

Nirvana is the complete realization of the middle way that denies the extremist view of nihilism (Pali: Ucchedavaada), nor eternalism (Pali: Sassatavaada), nor the monism of "oneness with Brahman" (as taught in Hinduism). Nirvana is not eternalism, as the Buddha posits Anatta (not-self), so there is no immortality of a personal self, nor is it nihilism:

- â¦which identifies the psycho-physical person (naama-ruupa) with the body (ruupa), rejecting human effort and the world hereafter (para loka). When the body is dead, it entails the total annihilation of the psycho-physical person, without the continuity of the consciousness for bearing moral retribution of his deeds done.[2]

Therefore, the early Buddhist concept of nirvana differs both from the Vedic concept of nirvana as described in several Upanishads, especially the Nirvana Upanishad, as well as the Vedic concept of moksha, the union of the atman (soul) with Brahman, nor is it the same as Heaven in many other religions.

Notes

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Collins, Steven. 1998. Nirvana and Other Buddhist Felicities. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521570549

- Kabit-Zinn, Jon. 2005. Wherever You Go, There You Are. Hyperion. ISBN 1401307787

- Welbon, Guy Richard. 1969. The Buddhist Nirvana and Its Western Interpreters. Chicago: University of Chicago. ASIN: B000GZWMD2

- Yamamoto, Kosho. 2000. Mahayanism: A Critical Exposition of the Mahayana Mahaparinirvana Sutra. London: Nirvana Publications.

External links

All links retrieved June 30, 2025.

- Buddha - A Hero's Journey to Nirvana.

- Salvation Versus Liberation, A Buddhist View of Paradise Worlds.

- Mind Like Fire Unbound â a discussion of fire imagery as used in the Buddha's time.

- A Buddhist practice based on the four stages of the Buddha's enlightenment that lead him to Nirvana.

- The Life of Buddha in Legend and Art.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.