North German Confederation

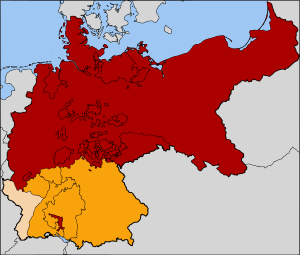

The North German Confederation (Norddeutscher Bund), came into existence in August 1866, as a military alliance of twenty-two states of northern Germany with the Kingdom of Prussia as the leading state. In July 1867, it was transformed into a federal state. It provided the country with a constitution and was the building block of the German Empire, which adopted most parts of the federation's constitution and its flag. Unlike the German Confederation, the North German Confederation was in fact a true state. Its territory comprised the parts of the German Confederation north of the river Main, plus Prussia's eastern territories and the Duchy of Schleswig, but excluded Austria, Bavaria, Württemberg, Baden, and the southern parts of the Grand Duchy of Hesse.

The North German Confederation firmly established Prussia at the wheel of the German state. Popularly described as an army with a state rather than a state with an army, this meant that its military tradition and expansionist ambitions were inherited by the new entity. Democratically weak, the new German state or empire into which the Confederation evolved, was ambitious and expansionist in ethos. At a time when Europe's monarchies were adopting [[[parliament|parliamentary]] systems limiting the role of kings and queens, the German Emperor exercised almost autocratic authority. This set the stage for Germany's role in World War I and World War II under leaders who were convinced that Germans deserved to dominate and rule over others because of the superior qualities of the German people. Both the ideas of perpetual conquest and of the racial superiority of Nordic people has been traced back to the Prussian legacy, placed center stage by the Confederation and by its successor states through Empire to the Third Reich.

Historical background=

When the Holy Roman Empire was wound up in 1806, the German speaking states decided to form a Confederation as a step towards German re-unification. It was created by the Congress of Vienna in 1815, tasked with re-drawing Europe's borders after the Napoleonic Wars under the Presidency of the House of Habsburg. Under the empire, about 200 small German states had existed. The Confederacy comprised 38 states and three free-cities, due to the merging of states no longer regarded as viable. The confederation was briefly suspended in 1848 due to dispute about the shape that unification should take but it was reconstituted in 1850. During this period, Prussia vied with Austria as the dominant power. Many very small principalities formed part of this Confederation. However, Prussia's Chancellor, Otto von Bismarck preferred a more unified state, one that would resemble France and Great Britain more closely. Austria-Hungary was a large multi-ethnic state that would, if part of a new German state, dominate and compromise its German identity. In order to exclude Austria from the process, Prussia and her allies declared war on Austria in 1866. The new German state was to have a "common [[nationalism|national culture" not many cultures.[1] Belief in the racial superiority of Nordic people, as well as the ideas of "perpetual war and conquest" has been traced back to the Prussian legacy.[2] Prussia's very efficient and pervasive bureaucracy also became integral to the new state. The formation in 1866 of the North German confederation was a major step towards German re-unification. It cemented Prussian control over northern Germany, and through the Zollverein (Customs Union) and secret peace treaties, agreed with the southern states the day before the Peace of Prague it extended Prussia's zone of influence into southern Germany as well.

Constitution

The federation came into force on July 1, 1867, with the King of Prussia, William I, as its President, and Bismarck as Chancellor.Bismarck was tasked with drafting a Constitution for the Confederation. This constitution granted huge powers to the chancellor, who was appointed by the President of the Bundesrat (Prussia). This was because the constitution made the chancellor responsible, but not accountable, to the Reichstag. This therefore allowed him the benefit of being the link between the emperor and the people. The Chancellor retained powers over the military budget. Laws also prevented certain civil servants becoming members of the Reichstag, those who were Bismarck's main opposition in the 1860s.

The states were represented in the Bundesrat (Federal Council) with 43 seats (of which Prussia held 17). Most notably, Bismarck introduced universal male suffrage into the confederation for elections to the Reichstag. The Bundesrat membership was extended before 1871 with the creation of the Zollverein Parliament in 1867, an attempt to create closer unity with the southern states by permitting representatives to be sent to the Bundersrat. Each state retained its own government but the military was controlled by the Confederation. Arguably, an Austrian dominated Confederation would have developed a stronger democratic tradition; often looked on as an autocratic state, in fact, by 1900, "to a 'unique extent' Austro-Hungary was becoming 'a multi-national democratic federation, able to offer its peoples the economic benefits of a huge market, legally protected equality in status, and the security that was the Empire's traditional boon."[3]

Following Prussia's victory over the Second French Empire in the Franco-Prussian War of 1871, Bavaria, Württemberg, and Baden (together with parts of the Grand Duchy of Hesse which had not originally joined the federation), now grouped together with the various states of the Federation to form the German Empire, with William I taking the new title of German Emperor (rather than Emperor of Germany as Austria was not included). Benz suggests that the Franco-Prussian war provided Bismarck with the opportunity he wanted to convince the southern states that it was in their interest to join his German state. The excuse for the war was French opposition to succession to the Spanish throne of a member of the Prussian royal house.[1]

Postal Union

One of the functions of the confederation was to handle mail and issue postage stamps; for details.

List of member states

- Prussia (Preußen)

(including Lauenburg)

- Saxony (Sachsen)

Grand duchies (Großherzogtümer)

- Hesse (Hessen) (Only Upper Hesse, the province north of the Main River)

- Mecklenburg-Schwerin

- Mecklenburg-Strelitz

- Oldenburg Oldenburg

- Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach (Sachsen-Weimar-Eisenach)

Duchies (Herzogtümer)

- Anhalt

- Brunswick (Braunschweig)

- Saxe-Altenburg (Sachsen-Altenburg)

- Saxe-Coburg and Gotha (Sachsen-Coburg und Gotha)

- Saxe-Meiningen (Sachsen-Meiningen) Meiningen

Principalities (Fürstentümer)

- Lippe Detmold

- Reuss, junior line Gera

- Reuss, senior line Greiz

- Schaumburg-Lippe Bückeburg

- Schwarzburg-Rudolstadt Rudolstadt

- Schwarzburg-Sondershausen Sondershausen

- Waldeck-Pyrmont Arolsen

Free Hanseatic cities (Freie Hansestädte)

- Bremen

- Hamburg

- Lübeck

Legacy

The constitution of the North German Federation, "with slight changes" continued to serve as the constitution of the German Empire.[4] Both the Confederation and the empire have been described as "Prussia writ large." The constitution gave little power to parliament, which was consequently "the most distinguished debating chamber in Europe." The King of Prussia, as President, appointed the Chancellor and with the Prussian King at the center and the military under Prussian control, the militaristic traditions of the Prussian House of Hohenzollern also took center stage.

Prussia has been described as an army with a state rather than a state with an army.[5] Wilhelm I's successor, Kaiser Wilhelm II who remained in power until the monarchy was abolished after World War I had an expansionist agenda; he wanted Germany to possess an empire that would rival those of other European powers. The constitution that he inherited enabled him to exercise a great deal of influence over the political process, so much so that it was the king and his "court, rather than the Chancellor and his 'men" who exercised political power and decision-making" from the 1890s on.[6] This weak democratic foundation contributed to Adolf Hitler's rise to power; he only ever achieved 37 percent of the popular vote in 1932 but by 1933 had acquired emergency powers and could change the constitution and pass laws "without consulting parliament."[7]

Spending as much as two-thirds and sometimes more of the state budget on the Army, ordinary citizens were taught that they existed for the state; "their role in life was one of obedience, work, sacrifice and duty."[8] This ethos lies behind Germany's role in both world wars. One the one hand, it is difficult to argue for any direct cause and effect between Bismarck, creator of both the North German Confederacy and of the German Empire and Hitler. On the other hand, the two men shared pride in the ideal of a strong Germany, believed that greatness was the German destiny, dealt ruthlessly with opponents and centralized power in their own hands. Prussia's very efficient and pervasive bureaucracy, integral to the new state, provided Hitler the tool he needed to rule through bureaucrats rather than elected representatives.

Notes

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Benz, Wolfgang, and Thomas Dunlap. 2006. A Concise History of the Third Reich. Weimar and now, 39. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. ISBN 9780520234895.

- Dill, Marshall. 1970. Germany; a Modern History. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 9780472071012.

- Eley, Geoff. 1986. From Unification to Nazism: Reinterpreting the German Past. Boston, MA: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 9780049430389.

- Feuchtwanger, E.J. 2001. Imperial Germany, 1850-1918. London, UK: Routledge. ISBN 9780203189498.

- Kitson, Alison. 2001. Germany, 1858-1990: Hope, Terror, and Revival. Oxford advanced history. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199134175.

- Lieven, D.C.B. 2001. Empire: The Russian Empire and its Rivals. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300088595.

- Röhl, John C.G. 1996. The Kaiser and his Court: Wilhelm II and the Government of Germany. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521565042.

- Schulte-Peevers, Andrea. 2004. Germany. Footscray, AU: Lonely Planet Publications. ISBN 9781740594714.

- Shirer, William L. 1990. The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 9780671728694.

- Taylor, A.J.P. 2003. Bismarck, the Man and the Statesman. Phoenix Mill, UK: Sutton Pub. ISBN 9780750932745.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.