Nuwa

For the character Nu Wa in the Chinese novel Fengshen Yanyi, see Nu Wa Niang Niang

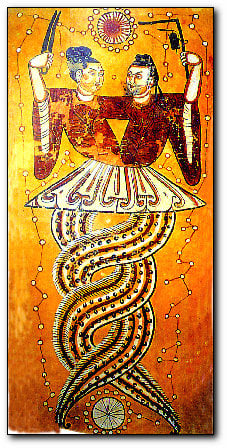

In Chinese mythology, Nüwa (Traditional Chinese: 女媧; Simplified Chinese: 女娲; Pinyin: nǚwā) is a Chinese mythological character best known for creating and reproducing people after a great calamity. Some scholars suggest that the female Nuwa was the first creative Chinese deity, appropriate for ancient Chinese matriarchal society, in which childbirth was seen to be a miraculous occurrence, not requiring the participation of the male. The earliest myths represent Nuwa as a female in a procreative role; in later stories Nuwa has a husband/brother named Fuxi, who assumes primary importance. In ancient art, Nuwa is often depicted with a snake body and a human head.

According to myth, Nuwa shaped the first human beings out of yellow clay, then grew tired, dipped a rope into the mud and swung it around. The blobs of mud that fell from the rope became common people, while the handcrafted ones became the nobility. Another myth recounts how Nuwa saved mankind from terrible flooding and destruction.

Overview

In Chinese mythology, Nüwa was a mythological character, generally represented as a female. (Other later traditions attribute this creation myth to either Pangu or Yu Huang.) Nüwa appears in many Chinese myths, performing various roles as a wife, sister, man, tribal leader (or even emperor), creator, or maintainer. Most myths present Nüwa as female in a procreative role, creating and reproducing people after a great calamity. Nuwa is also associated with a deluge myth, in which the water god Gong Gong smashed his head against Mount Buzhou (不周山), a pillar holding up the sky, collapsing it and causing great floods and suffering among the people.

The earliest literary reference to Nuwa, in Liezi (列子) by Lie Yukou (列圄寇, 475 - 221 B.C.E.), describes Nüwa repairing the heavens after a great flood, and states that Nüwa molded the first people out of clay. The name “Nuwa” first appears in "Elegies of Chu" (楚辞, or Chuci), chapter 3: "Asking Heaven" by Qu Yuan (屈原, 340 - 278 B.C.E.), in another account of Nuwa molding figures from the yellow earth, and giving them life and the ability to bear children. Demons then fought and broke the pillars of the Heavens, and Nüwa worked unceasingly to repair the damage, melting down the five-colored stones to mend the Heavens.

Some scholars suggest that the female Nuwa was the first creative Chinese deity. Ancient Chinese society was matriarchal and primitive. Childbirth was seen to be a miraculous occurrence, not requiring the participation of the male, and children only knew their mothers. As the reproductive process became better understood, ancient Chinese society moved towards a patriarchal system and the male ancestral deity, Fu Xi, assumed primary importance.[1]

By the Han Dynasty (206 – 220 C.E.), Nuwa was described in literature with her husband Fuxi as the first of the Three August Ones and Five Emperors, and they were often called the "parents of humankind." In the earliest Chinese dictionary, Shuowen Jiezi (說文解字), by Xu Shen (58 - 147 C.E.), Nüwa is said to have been both the sister and the wife of Fuxi. However, paintings depicting them joined as half people, half snake or dragon, date as far back as the Warring States period (fifth century B.C.E. to 220 B.C.E.). A stone tablet from the Han dynasty, dated 160 C.E., depicts Fu Hsi with Nüwa, who was both his wife and his sister.

Some of the minorities in South-Western China hail Nüwa as their goddess and some festivals, such as the 'Water-Splashing Festival,' are in part a tribute to her sacrifices. Nüwa is also the traditional divine goddess of the Miao people.

Creation Myth

Nuwa is not considered a creator of the entire physical universe, but a creator and protector of animals and people. It is said that Nüwa existed in the beginning of the world. The earth was a beautiful place with blossoming trees and flowers, and full of animals, birds, fish and all living creatures. But as she wandered about it Nüwa felt very lonely, so she began to create animals. On the first day she created chickens. On the second day she created dogs. On the third day she created sheep. On the fourth day she created pigs. On the fifth day she created cows. On the sixth day she created horses. On the seventh day, she bent down and took up a handful of yellow clay, mixed it with water and molded a figure in her likeness. As she worked, the figure came alive - the first human being. Nüwa was pleased with her creation and went on making more figures of both men and women. They danced around her, and her loneliness was dispelled. She created hundreds of figures, but grew tired of the laborious process. Then she dipped a rope in the clay mud, and swung it around her. Soon the earth around her was covered with lumps of mud. The handmade figurines became the wealthy and the noble; those that arose from the splashes of mud were the poor and the common. A variation on this story relates that some of the figures melted in the rain as Nüwa was waiting for them to dry, and that in this way sickness and physical abnormalities came into existence.

Deluge Myth

There was a quarrel between two of the more powerful gods, Gong Gong, the God of Water and Zhu Rong, the God of Fire, and they decided to settle it with a fight. They fought all the way from heaven to earth, wreaking havoc everywhere. When the God of Water Gong Gong saw that he was losing, he smashed his head against Mount Buzhou (不周山), a mythical peak supposed to be northwest of the Kunlun range in southern Xinjiang which was said to be a pillar holding up the sky. The pillar collapsed, half the sky fell in, the earth cracked open, forests went up in flames, flood waters sprouted from beneath the earth and dragons, snakes and fierce animals leaped out at the people. Many people were drowned and more were burned or devoured.

Nüwa was grieved that mankind which she had created should undergo such suffering. She decided to mend the sky and end this catastrophe. She melted together the five colored stones and with the molten mixture patched up the sky. Then she killed a giant turtle and used its four legs as four pillars to support the fallen part of the sky. She caught and killed a dragon and this scared the other beasts away from the land of Qi. Then she gathered and burned a huge quantity of reeds and with the ashes stopped the flood from spreading, so that the people could live happily again.

The only trace left of the disaster, the legend says, was that the sky slanted to the northwest and the earth to the southeast, and so, since then, the sun, the moon and all the stars turn towards the west and all the rivers run southeast. Other versions of the story describe Nüwa going up to heaven and filling the gap with her body (half human half serpent) and thus stopping the flood. Because of this legend, some of the minorities in South-Western China hail Nüwa as their goddess and festivals such as the 'Water-Splashing Festival' are, in part, a tribute to her sacrifices.

Nüwa and other traditions

The Nüwa flood stories share common elements with other global deluge traditions, such as:

- global flood or calamity (Gong Gongs destruction)

- destruction of humanity and animals (explicitly described)

- select pair survives calamity (Fuxi & Nuwa in most Chinese versions)

- select pair survives in a boat or gourd (Zhuang version)

- similarity of names (Nuwa, Noah, Nu, Manu, Oannes, etc.)

- rebuilding humanity after devastation(explicitly described)

- colorful heavenly object (5 colored pillar, rainbow)

Similarly, aspects of the Nuwa creation myths, such as the creation of humans from mud, the Fuxi-Nuwa brother-sister pair, the half-snake element, and survival of a flood, resemble creation myths from other cultures. Nuwa and Fuxi resemble the Japanese brother-and-sister deities Amaterasu and Susanoo.

Nüwa in Primary Sources

Below are some of the sources that describe Nüwa, in chronological order. These sources do not include local tribal stories or modern recreations. 1) (475 - 221 B.C.E.) author: Lie Yukou (列圄寇), book: Liezi (列子), chapter 5: "Questions of Tang" (卷第五 湯問篇), paragraph 1: account: "Nüwa repairs the heavens" Detail: Describes Nüwa repairing the heavens after a great flood. It also states that Nüwa molded the first people out of clay.

2) (340 - 278 B.C.E.) author: Qu Yuan (屈原), book: "Elegies of Chu" (楚辞, or Chuci), chapter 3: "Asking Heaven" (天問, or Wentian), account: "Nüwa Mends The Firmament" Detail: The name Nüwa first appears here. This story states that Nüwa molded figures from the yellow earth, giving them life and the ability to bear children. Demons then fought and broke the pillars of the Heavens. Nüwa worked unceasingly to repair the damage, melting down the five-colored stones to mend the Heavens.

3) (179 - 122 B.C.E.) author: Liu An (劉安), book: Huainanzi (淮南子), chapter 6: Lanmingxun (覽冥訓), account: "Nüwa Mended the Sky" Detail: In remote antiquity, the four poles of the Universe collapsed, and the world descended into chaos: the firmament was no longer able to cover everything, and the earth was no longer able to support itself; fire burned wild, and waters flooded the land. Fierce beasts ate common people, and ferocious birds attacked the old and the weak. Nüwa tempered the five-colored stone to mend the Heavens, cut off the feet of the great turtle to support the four poles, killed the black dragon to help the earth, and gathered the ash of reed to stop the flood. Variation: The four corners of the sky collapsed and the world with its nine regions split open.

4) (145 - 90 B.C.E.) author: Sima Qian (司馬遷), book: Shiji (史記), section 1: BenJi (本紀), chapter 1: prolog Detail: Nüwa is described as a man with the last name of Feng, who is related to Fuxi; and possibly related to Fenghuang (鳳凰, pinyin: fènghuáng).

5) (58 - 147 C.E.) author: Xu Shen (許慎), book: Shuowen Jiezi (說文解字), entry: Nüwa Detail: The Shuowen is China's earliest dictionary. In it, Nüwa is said to have been both the sister and the wife of Fuxi. Nüwa and Fuxi were pictured as having snake-like tails interlocked in an Eastern Han dynasty (25 - 220) mural in the Wuliang Temple in Jiaxiang county, Shandong province.

6) (618 - 907 C.E.) author: LiRong (李榮), book: Duyi Zhi (獨异志); vol 3, account: "opening of the universe" Detail: There was a brother and a sister living on the Kunlun Mountain, and there were no ordinary people at that time. The sister's name was Nüwa. The brother and sister wished to become husband and wife, but felt shy and guilty about this desire. So the brother took his younger sister to the top of the Kunlun Mountain and prayed: "If Heaven allows us to be man and wife, please let the smoke before us gather; if not, please let the smoke scatter." The smoke before them gathered together. So Nüwa came to live with her elder brother. She made a fan with grass to hide her face. (The present custom of women covering their faces with fans originated from this story.)

7) (618 - 907 C.E.) author: Lu Tong (盧同), book: Yuchuan Ziji (玉川子集), chapter 3 Detail: characters: "與馬異結交詩" 也稱 "女媧本是伏羲婦," pinyin: "Yu Mayi Jie Jiao Shi" YeCheng "Nüwa ben shi Fuxi fu," English: "NuWa originally is Fuxi’s wife"

8) (618 - 907 C.E.) author: Sima Zhen (司馬貞), book: "Four Branches of Literature Complete Library" (四庫全書, or Siku Quanshu) , chapter: "Supplemental to the Historic Record – History of the Three August Ones" Detail: The three August Ones ([[Three August Ones and Five Emperors|San Huang]]) are: Fuxi, Nüwa, Shennong; Fuxi and Nüwa were brother and sister, and have the same last name "Fong" or Feng. Note: SimaZhens commentary is included with the later Siku Quanshu compiled by Ji Yun (紀昀) & Lu Xixiong (陸錫熊 ).

9) (960 - 1279 C.E.) author: Li Fang (李昉), collection: Songsi Dashu (宋四大書), series: "Taiping Anthologies for the Emperor" (太平御覽, or Taiping Yulan), book: Vol 78, chapter "Customs by Yingshao of the Han Dynasty" Detail: States that there were no men when the sky and the earth were separated. Nüwa used yellow clay to make people. The clay was not strong enough, so she put ropes into the clay to make the bodies erect. It was also said that she prayed to gods to let her be the goddess of marital affairs. (Variations of this story exist.)

Notes

- ↑ Association for Promoting the Protection and Use of the Imperial Temples of Emperors of Successive Dynasties in Beijing, along with the Administrative Office of the Imperial Temples of Emperors of Successive Dynasties in Beijing. 2007. Worshiping the Three Sage Kings and Five Virtuous Emperors - The Imperial Temple of Emperors of Successive Dynasties in Beijing. (Beijing: Foreign Language Press. ISBN 9787119046358).

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Association for Promoting the Protection and Use of the Imperial Temples of Emperors of Successive Dynasties in Beijing, along with the Administrative Office of the Imperial Temples of Emperors of Successive Dynasties in Beijing. 2007. Worshiping the Three Sage Kings and Five Virtuous Emperors - The Imperial Temple of Emperors of Successive Dynasties in Beijing. Beijing: Foreign Language Press. ISBN 9787119046358

- Birrell, Anne. 1993. Chinese mythology: an introduction. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0801845955 ISBN 9780801845956

- Giddens, Sandra, and Owen Giddens. 2006. Chinese mythology. Mythology around the world. New York: Rosen Pub. Group. ISBN 9781404207691

- Sanders, Tao Tao Liu. 1983. Dragons, gods & spirits from Chinese mythology. World mythologies series. New York: Schocken Books. ISBN 0805237992 ISBN 9780805237993

- Yang, Lihui, and Deming An. 2005. Handbook of Chinese mythology. Handbooks of world mythology. Santa Barbara, Calif: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781576078068 ISBN 9781576078075

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.