Okinawa

| |

| Capital | Naha |

| Region | Ryūkyū Archipelago |

| Island | Okinawa |

| Governor | Hirokazu Nakaima |

| Area | 2,271.30 km² (44th) |

| - % water | 0.5% |

| Population (October 1, 2000) | |

| - Population | 1,318,218 (32nd) |

| - Density | 580 /km² |

| Districts | 5 |

| Municipalities | 41 |

| ISO 3166-2 | JP-47 |

| Website | www.pref.okinawa.jp/ english/ |

| Prefectural Symbols | |

| - Flower | Deigo (Erythrina variegata) |

| - Tree | Pinus luchuensis (ryūkyūmatsu) |

| - Bird | Okinawa woodpecker (Sapheopipo noguchii) |

Symbol of Okinawa Prefecture | |

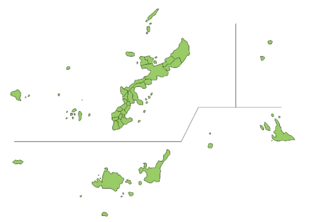

Okinawa Prefecture (沖縄県, Okinawa-ken;Okinawan: Uchinā) is one of Japan's southern prefectures, and consists of hundreds of the Ryūkyū Islands in a chain over 1,000 km long, which extends southwest from Kyūshū (the southwesternmost of Japan's main four islands) to Taiwan. Okinawa's capital, Naha, is located in the southern part of the largest and most populous island, Okinawa Island, which is approximately half-way between Kyūshū and Taiwan. The disputed Senkaku Islands (Chinese: Diaoyu Islands) are presently administered as part of Okinawa Prefecture.

The three tribal federations of the Ryukyu Islands were united in 1429, under the first Shō Dynasty. The Kingdom of Ryukyu was a Chinese tributary and remained semi-autonomous even after it was conquered by the Japanese Satsuma clan in 1609, serving as a middle ground for trade between the Japanese shogunate and China. Four years after the 1868 Meiji Restoration, the Japanese government officially annexed the kingdom and renamed it Ryūkyū han. Ryūkyū han became Okinawa Prefecture in 1879. Okinawa Island was the site of the Battle of Okinawa, the largest amphibious assault of World War II. In 1972, the U.S. government returned the islands to Japanese administration. The United States Forces Japan (USFJ) have maintained a large military presence there, arousing some opposition from local residents. Okinawa’s warm temperatures, beautiful beaches and abundant coral reefs attract large numbers of tourists, and several Japanese baseball teams conduct their winter training there.

Geography

Major islands

The set of islands belonging to the prefecture is called Ryūkyū Shotō (琉球諸島). Okinawa's inhabited islands are typically divided into three geographical archipelagos. From northeast to southwest:

- Okinawa Islands

- Ie-jima

- Kume

- Okinawa Honto

- Tokashiki

- Miyako Islands

- Miyako-jima

- Yaeyama Islands

- Iriomote

- Ishigaki

- Yonaguni

Okinawa Island, approximately half-way between Kyūshū and Taiwan, is the largest in the Ryūkyū Islands archipelago; it is about 70 miles (112 km) long and 7 miles (11 km) wide. Okinawa Island has an area of 463 square miles (1,199 square km). The area of the entire prefecture is about 871 square miles (2,255 square km). Okinawa's capital, Naha, is located in the southern part of the largest and most populous island, Okinawa Island.

Geography, climate and natural resources

The island is largely composed of coral rock, and rainwater filtering through that coral has given the island many caves, which played an important role in the Battle of Okinawa. Gyokusendo, an extensive limestone cave in the southern part of Okinawa's main island, is a popular tourist attraction.

Okinawa is a major producer of sugar cane, pineapple, papaya, and other tropical fruit. Primary economic activities are tuna fishing, cattle raising, sugar refining, and pineapple canning. Sweet potatoes, rice, and soybeans are also grown on the island, and textiles, sake (rice wine), and lacquerware are manufactured. Offshore wells yield petroleum.

Okinawa is said to have the most beautiful beaches in all of Japan and normally enjoys temperatures above 20 degrees Celsius for most of the year. Okinawa and the many islands that make up the prefecture boast some of the most abundant coral reefs found in the world. Rare blue corals are found off of Ishigaki and Miyako islands, as are numerous other species throughout the island chain. Many coral reefs are found in this region of Japan and wildlife is abundant. Sea turtles return yearly to the southern islands of Okinawa to lay their eggs. During the summer months, swimmers are warned about poisonous jellyfish and other dangerous sea creatures. A species of wildcat, said to have roamed Iriomote island in the East China Sea for 200,000 years, was discovered in 1967.[1]

The Southeast Botanical Gardens (東南植物楽園, Tōnan shokubutsu rakuen) in Okinawa City contains 2,000 tropical plant species.

History

Early history

The oldest evidence of human existence in the Ryukyu islands has been discovered in Naha City and Yaese Town[2]. Some human bone fragments from the Paleolithic era were unearthed, but there is no clear evidence of Paleolith remains. Japanese Jōmon influences are dominant in the Okinawa Islands, although clay vessels in the Sakishima Islands have a commonality with those in Taiwan.

Continuous human habitation can be traced as far back as 4000 years ago. Evidence of southward migration from Kyūshū has been found in two northern island groups (Amami-Oshima and Okinawa); evidence in the two southern island groups (Miyako and Yaeyama) points to Melanesian cultural strains from the South.[3]

The first written mention of the word Ryukyu is found in the Book of Sui (one of the Twenty-Four Histories of imperial China, completed in 636 C.E.). This “Ryukyu” might refer to Taiwan, rather than to the Ryukyu islands. The earliest written reference to Okinawa, the Japanese name for the islands, is found in the biography of Jianzhen, written in 779. Agricultural societies established in the eighth century developed slowly until the twelfth century. The location of the islands, in the center of the East China Sea relatively close to Japan, China and South-East Asia, eventually allowed the Ryūkyū Kingdom to become a prosperous trading nation.

Ryūkyū Kingdom

According to the three Ryūkyū historical annals&mdash, Chūzan Seikan, (中山世鑑, Mirror of Chūzan), Chūzan Seifu (中山世譜, Genealogy of Chūzan), and Kyūyō (球陽, Chronicle of Ryūkyū)—the history of the Ryūkyū Kingdom began with the Tenson Dynasty (天孫王朝, Dynasty of Heavenly Descent), which was said to have lasted 17,000 years. Many historians today believe that this is a mythological legend created in the sixteenth or seventeenth century to lend legitimacy to the ruling dynasty, the Shō family, and give them prominence over other local aristocratic families.

The Tenson Dynasty ended with three kings of the Shunten Line (舜天王朝), lasting from 1187 to 1259. According to Chūzan Seikan, written by Shō Shōken, the founder of the dynasty was a son of Minamoto no Tametomo, a Japanese aristocrat and relative of the Imperial family who was exiled to the Izu Islands after he failed to gain power in the Kyoto court. Some Japanese and Chinese scholars claim that the Shunten dynasty is also an invention of the Shō family historians.

In the fourteenth century, small domains scattered on Okinawa Island were unified into three principalities: Hokuzan (北山, Northern Mountain), Chūzan (中山, Central Mountain), and Nanzan (南山, Southern Mountain). This was known as the Three Kingdoms or Sanzan (三山, Three Mountains) period. These three principalities, or tribal federations led by major chieftains, battled, and Chūzan emerged victorious, receiving Chinese investiture in the early fifteenth century. The ruler of Chūzan passed his throne to king Hashi; he received the surname "Shō" from the Ming emperor in 1421, becoming known as Shō Hashi] (尚巴志). Hashi had already conquered Hokuzan in 1416 and subjugated Nanzan in 1429, uniting the island of Okinawa for the first time, and founding the first Shō Dynasty.

Shō Hashi adopted the Chinese hierarchical court system, built Shuri Castle and the town as his capital, and constructed Naha harbor. Several generations later, in 1469, King Shō Toku died without a male heir; a palatine servant declared he was Toku's adopted son and gained Chinese investiture. This pretender, Shō En, began the Second Shō Dynasty. Ryūkyū's golden age occurred during the reign of Shō Shin, the second king of that dynasty, who reigned from 1478-1526.

The kingdom established tributary relations with China during its Ming and Qing Dynasties. It also developed trade relations with Japan, Korea and many Southeast Asian countries, including Siam, Pattani, Malacca, Champa, Annam, and Java. Between the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, the Ryūkyū Kingdom emerged as the main trading intermediary in Eastern Asia. Japanese products—silver, swords, fans, lacquer-ware, folding screens—and Chinese products—medicinal herbs, minted coins, glazed ceramics, brocades, textiles—were traded within the kingdom for Southeast Asian sappanwood, rhino horn, tin, sugar, iron, ambergris, Indian ivory and Arabian frankincense. Altogether, 150 voyages between the kingdom and Southeast Asia on Ryūkyūan ships were recorded, with 61 of them bound for Siam, ten for Malacca, ten for Pattani and eight for Java, among others.

During this period, many Gusukus, similar to castles, were constructed.

Commercial activities in the kingdom diminished around 1570 with the rise of Chinese merchants and the intervention of Portuguese and Spanish ships, corresponding with the start of the Red Seal Ship system in Japan.

Japanese invasion (1609)

Around 1590, Toyotomi Hideyoshi asked the Ryūkyū Kingdom to aid in his campaign to conquer Korea. If successful, Hideyoshi intended to then move against China; the Ryūkyū kingdom, as a tributary state of the Ming Dynasty, refused. The Tokugawa shogunate that emerged following Hideyoshi's fall, authorized the Shimazu family—feudal lords of the Satsuma domain (present-day Kagoshima prefecture)—to send an expeditionary force to conquer the Ryūkyūs. The occupation of the Ryūkyūs occurred with a minimum of armed resistance, and King Shō Nei was taken as a prisoner to the Satsuma domain and later to Edo—modern day Tokyo. When he was released two years later, the Ryūkyū Kingdom regained a degree of autonomy.

Since complete annexation would have created a problem with China, the sovereignty of Ryūkyū was maintained. The Satsuma clan was able to profit considerably by trading with China through Ryūkyū, during a period in which foreign trade was heavily restricted by the shogunate.

Though Satsuma maintained strong influence over the islands, the Ryūkyū Kingdom maintained considerable degree of domestic political freedom for over two hundred years. Four years after the 1868 Meiji Restoration, the Japanese government, through military incursions, officially annexed the kingdom and renamed it Ryūkyū han. At the time, the Qing Dynasty of China still asserted sovereignty over the islands, since the Ryūkyū Kingdom had been a tributary nation of China. Okinawa han became a prefecture of Japan in 1879, seven years later than all the other hans.

Battle of Okinawa

The Battle of Okinawa, also known as Operation Iceberg, the largest amphibious assault in the Pacific Theater of World War II,[4][5] was fought on the island of Okinawa. The 82-day battle lasted from late March through June 1945. The nature of Japanese resistance, resulting in such massive losses of life, led ultimately to the decision by U.S. President Truman to use the atomic bomb over Hiroshima, six weeks later.[6]

The battle has been referred to as the "Typhoon of Steel" in English, and tetsu no ame ("rain of steel") or tetsu no bōfū ("violent wind of steel") in Japanese, because of the ferocity of the fighting, the intensity of the gunfire, and the sheer numbers of Allied ships and armored vehicles that assaulted the island. The Japanese lost over 90,000 troops, and the Allies (mostly the United States) suffered nearly 50,000 casualties, with over 12,000 killed in action, before they were able to gain control of the island. Hundreds of thousands of civilians were killed, wounded or attempted suicide. Such slaughter led to a great desire to end the war as quickly as possible. To mark this tragedy, a Memorial plaza was built, with over 230,000 names of people who perished during the Battle of Okinawa including 14,000 American soldiers, are engraved on memorials at the Cornerstone of Peace.

After World War II

Following the Battle of Okinawa and the end of World War II in 1945, Okinawa was under the United States administration for 27 years. During this trusteeship rule, the U. S. Air Force established numerous military bases on the Ryukyu islands.

In 1972, the U.S. government returned the islands to Japanese administration. Under the Treaty of Mutual Cooperation and Security, the United States Forces Japan (USFJ) have maintained a large military presence in Okinawa. Approximately 27,000 personnel, including 15,000 Marines, contingents from the Navy, Army and Air Force, and their 22,000 family members, are stationed in Okinawa.[7] U.S. military bases occupy 18 percent of the main island, and 75 percent of all USFJ bases are located in Okinawa prefecture.[8]

Language and culture

Okinawa has historically been a separate nation, and Okinawan language and culture differ considerably from those of mainland Japan.

Language

Numerous Ryukyuan languages, which are more or less incomprehensible to Japanese speakers, are still spoken, though their use is declining as the younger generation speaks mainland Japanese. Many linguists outside Japan consider Ryukyuan languages as different languages from Japanese, while Japanese linguists and Okinawans generally perceive them as "dialects." Standard Japanese is almost always used in formal situations. In informal situations, the de facto everyday language among Okinawans under age 60 is mainland Japanese spoken with an Okinawan accent, called ウチナーヤマトグチ (Uchinā Yamatoguchi "Okinawan Japanese"). Uchinā Yamatoguchi is often mistaken for the true Okinawan language ウチナーグチ (Uchināguchi "Okinawan language"), which is still used in traditional cultural activities, such as folk music, or folk dance. A radio news program is also broadcast in the language [7].

Religion

Okinawa has indigenous religious beliefs, bearing a resemblance to the Shintoism of mainland Japan, and generally characterized by ancestor worship and respect for relationships between the living, the dead, and the gods and spirits of the natural world. Awe-inspiring natural objects, special geologic formations, and locations associated with ancestors are regarded with reverence.[9]

Cultural influences

Okinawan culture bears traces of its various trading partners. The island’s customs show evidence of Chinese, Thai and Austronesian influences. Okinawa's most famous cultural export is probably karate, thought to be a synthesis of Chinese kung fu with traditional Okinawan martial arts. A ban on weapons in Okinawa for two long periods after the invasion, and forced annexation by Japan during the Meiji Restoration period, probably contributed to the development of karate.

Another traditional Okinawan product that owes its existence to Okinawa's trading history is awamori—an Okinawan distilled spirit made from indica rice imported from Thailand.

Other cultural characteristics

The people of Okinawa maintain a strong tradition of pottery, textiles, and glass making.

Other prominent examples of Okinawan culture include the sanshin—a three-stringed Okinawan instrument, closely related to the Chinese sanxian, and ancestor of the Japanese shamisen, somewhat similar to a banjo. Its body is often bound with snakeskin (from pythons, imported from elsewhere in Asia, rather than from Okinawa's poisonous habu, which are too small for this purpose). Okinawan culture also features the eisa dance, a traditional drumming dance. A traditional craft, the fabric named bingata, is made in workshops on the main island and elsewhere.

Architecture

Okinawa has many remains of a unique type of castle or fortress called Gusuku. These are believed to be the predecessors of Japan's castles. Castle ruins and other sites in Okinawa were officially registered as part of The World Heritage, in November, 2000. The preservation and care of these sites, which are regarded by Okinawans as symbolic of the Ryuku cultural heritage, are a top priority for both the Okinawan people and the government.[10]

While most Japanese homes are made of wood and allow the free circulation of air to combat humidity, typical modern homes in Okinawa are made from concrete, with barred windows for protection from flying debris during the regular typhoons. Roofs are also designed to withstand strong winds; tiles are individually cemented in place and not merely layered, as on many homes elsewhere in Japan.

Many roofs also display a statue resembling a lion or dragon, called a shisa, which is said to protect the home from danger. Roofs are typically red in color and are inspired by Chinese design.

Demography

Okinawa prefecture age pyramid as of October 1, 2003

(per 1000's of people)

| Age | People |

|---|---|

| 0-4 | |

| 5-9 | |

| 10-14 | |

| 15-19 | |

| 20-24 | |

| 25-29 | |

| 30-34 | |

| 35-39 | |

| 40-44 | |

| 45-49 | |

| 50-54 | |

| 55-59 | |

| 60-64 | |

| 65-69 | |

| 70-74 | |

| 75-79 | |

| 80 + |

Okinawa Prefecture age pyramid, divided by sex, as of 1 October 2003

(per 1000's of people)

Okinawa has an unusually large number of centenarians, and of elderly people who have avoided the health problems and diseases of old age. Five times as many Okinawans live to be 100 than residents in the rest of Japan.[11]

Cities

Okinawa Prefecture includes eleven cities.

- Ginowan

- Ishigaki

- Itoman

- Miyakojima

- Nago

- Naha (capital)

- Nanjo

- Okinawa City (formerly Koza)

- Tomigusuku

- Urasoe

- Uruma

Towns and villages

These are the towns and villages in each district.

|

|

|

Education

The public schools in Okinawa are overseen by the Okinawa Prefectural Board of Education. The agency directly operates several public high schools [8]. The US Department of Defense Dependents Schools (DoDDS) operates 13 schools in Okinawa; seven of these schools are located on Kadena Air Base.

Okinawa is home to several universities, including Meiou University, Okinawa International University, Okinawa Kenritsu Geijutsu Daigaku, Okinawa University, and Ryūkyū University.

Sports

- F.C. Ryūkyū (Naha)

- Ryukyu Kings (Naha)

In addition, several baseball teams, including the Softbank Hawks, Yokohama BayStars, Chunichi Dragons, and Yakult Swallows, hold training during the winter in the prefecture as it is the warmest prefecture of Japan with no snow and higher temperatures than other prefectures.

Transportation

Okinawa is served by 13 airports.

Prior to World War II, railways were used in present-day Nishihara, Kadena, and Itoman. The first rail line in Okinawa, operating with handcars in Minami Daitō, opened in 1902, during the Meiji period. Okinawa Island's first railroad opened in 1910, for the transportation of sugar cane. The same year, the Okinawa Electric Railway (the predecessor of Okinawa Electric Company), opened the island's first streetcar line, between Daimon-mae and Shuri (5.7 km, 1067 mm gauge, 500 V). The prefectural government opened the Okinawa Prefectural Railways line between Naha and Yonabaru in December of 1914, and by the end of the Taisho period,(大正 lit. Great Righteousness, 1912 - 1926) had completed a railway system with three lines radiating from Naha: one to Kadena, one to Yonabaru, and one to Itoman. Bus and automobile transportation soon overtook the railways as a road system was developed, and bombing during World War II destroyed the remaining railway lines.

The Okinawa City Monorail Line (沖縄都市モノレール Okinawa Toshi Monorēru), or Yui Rail (ゆいレール Yui Rēru), in Naha, Okinawa, Japan, operated by Okinawa City Monorail Corporation (沖縄都市モノレール株式会社 Okinawa Toshi Monorēru Kabushiki-gaisha), opened on August 10, 2003, and is currently the only functioning public rail system in Okinawa Prefecture. It runs on an elevated track through the heart of Naha from Naha Airport in the west to Shuri (near Shuri Castle) in the east, stopping at 15 stations.[12] It takes 27 minutes and costs ¥290 to traverse its entire length of 12.8 km.

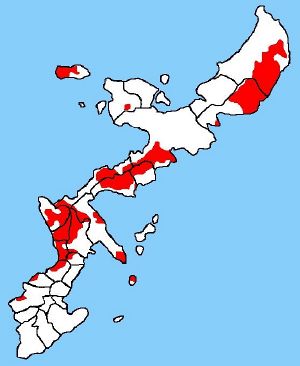

Opposition to U.S. military presence

Okinawa accounts for less than one percent of Japan's land, but hosts about two-thirds of the 40,000 American forces in the country.[8] Because the islands are close to China and Taiwan, the United States has 14 military bases, occupying 233 square kilometers (90 sq mi), or about 18 percent of the main island. Two major bases, Marine Corps Air Station Futenma and Kadena Air Base are located near residential areas. One third (9,852 acres) of the land used by the U.S. military is the Marine Corps Northern Training Area in the north of the island.

The relationship between U.S. troops stationed in Okinawa and the local community is strained. Noise pollution from military drills, aircraft accidents, environmental destruction[13], and crimes committed by U.S. military personnel[14]. have eroded local citizens' support for the U.S. military bases. According to an article published May 30, 2007, in the Okinawa Times newspaper, 85 percent of the Okinawans oppose the large presence of the USFJ and demand the consolidation, reduction and removal of US military bases from Okinawa.[15]

The Okinawan prefectural government and local municipalities have made several demands for the withdrawal of the US military since the end of World War II[16], but both the Japanese and U.S. governments consider the mutual security treaty and the USFJ essential for the security of the region. Plans for the relocation of the Marine Corps Air Station Futenma and other minor bases, announced after Okinawan protests in 1995, have been indefinitely postponed. On October 26, 2005, the governments of the United States and Japan agreed to move the Marine Corps Air Station Futenma base from its location in the densely populated city of Ginowan to the more northerly and remote Camp Schwab. Protests from environmental groups and residents over the construction of part of a runway at Camp Schwab, and from businessmen and politicians in the area around Futenma and Henoko over potential economic losses, have occurred [9].

The U.S. is also considering moving most of the 20,000 troops on Okinawa to new bases in Australia, Singapore, Malaysia, Vietnamese and the Philippines. As of 2006, 8,000 US Marines were being relocated from Okinawa to Guam[17]

According to historian Peter Schrijvers, an estimated 10,000 Japanese women were raped by American troops during the World War II Okinawa campaign.[10] During the first ten days of the occupation of the Kanagawa prefecture, 1,336 cases of rape by U.S. soldiers were reported.[18]

Another issue is the possible presence of nuclear weapons on U.S. bases and ships. [Japan]]'s Three Non-Nuclear Principles (非核三原則 Hikaku San Gensoku), a parliamentary resolution (never adopted into law) that has guided Japanese nuclear policy since the late 1960s, states that, Japan shall neither possess nor manufacture nuclear weapons, nor shall it permit their introduction into Japanese territory. The Diet formally adopted the principles in 1971. There is still speculation that not all of the 1200 nuclear weapons deployed to US bases in Okinawa before the reversion of Okinawa to Japanese administration in 1972 have been removed,[19] and that U.S. naval ships armed with nuclear weapons continue to stop at Okinawan ports.

Ports

The major ports of Okinawa include

- Naha Port

- Port of Unten [11]

- Port of Kinwan [12]

- Nakagusukuwan Port [13]

- Hirara Port [14]

- Port of Ishigaki [15]

United States military installations

- Kadena Air Base

- Marine Corps Base Camp Smedley D. Butler

- Marine Corps Air Station Futenma

- Camp Courtney

- Camp Foster

- Camp Hansen

- Camp Kinser

- Camp McTureous

- Camp Schwab

- Camp Gonsalves (Northern Training Area, Jungle Warfare Training Center)

- Naha Military Port

- Naval Facility White Beach

- Camp Lester

- Torii Station

- Camp Shields

See also

- Ryukyu Kingdom

- Battle of Okinawa

Notes

- ↑ Iriomote wildcat. A Wild Cat Living in an Primeval Natural Wilderness. [1].japan.org. Retrieved July 11, 2008.

- ↑ 山下町第1洞穴出土の旧石器について(Japanese), 南島考古 22. Retrieved May 27, 2008.

- ↑ Background and History. [2].Okinawa.com Travel. Retrieved May 26, 2008

- ↑ Laura Lacey. "Battle of Okinawa." The United States Navy assembled an unprecedented armada in April of 1945.militaryhistoryonline. Retrieved May 27, 2008.

- ↑ The American invasion of Okinawa was the largest amphibious assault of World War IIhistory.net. Retrieved May 27, 2008.

- ↑ The Battle of Okinawa.[3].globalsecurity.org. Retrieved July 12, 2008.

- ↑ 沖縄県の基地の現状(Japanese), Okinawa Prefectural Government. Retrieved May 27, 2008.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 .沖縄に所在する在日米軍施設・区域 Retrieved May 27, 2008.(Japanese), Japan Ministry of Defense

- ↑ Background and History.[4].Okinawa.com. Retrieved May 26, 2008

- ↑ The World Heritage. Treasures of the Earth and Mankind. Okinawa. Okinawa Index. Retrieved May 27, 2008.

- ↑ The Okinawan Centenarian Study The Okinawa Centenarian Study Retrieved May 27, 2008

- ↑ Monorails of Japan. Naha. [5].monorails.org. accessdate 2008-05-27

- ↑ Impact on the Lives of the Okinawan People (Incidents, Accidents and Environmental Issues), Okinawa Prefectural Government Retrieved May 27, 2008.

- ↑ 沖縄・米兵による女性への性犯罪 (Rapes and murders by the U.S. military personnel 1945-2000)Retrieved May 27, 2008.(Japanese), 基地・軍隊を許さない行動する女たちの会

- ↑ 語り継ぎたい「沖縄戦」 Retrieved May 27, 2008.(Japanese), Okinawa Times, May 13, 2007

- ↑ ..U.S. Military Bases in Okinawa Okinawa prefecture, website Military base Affairs Division Retrieved May 27, 2008

- ↑ DefenseLink News Article: Eight Thousand U.S. Marines to Move From Okinawa to Guam defenselink. Retrieved May 27, 2008.

- ↑ review of Peter Schrijvers. The GI War against Japan: American Soldiers in Asia and the Pacific during World War II. [6]. h-net.org. Retrieved July 12, 2008.

- ↑ 完全撤去の保証を与えよ(Japanese), Okinawa Times, October 22, 1999

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Hogg, Clayton L. 1973. Okinawa. This beautiful world, v. 41. Tokyo: Kodansha International [Distributed in the U.S. by Harper & Row, New York. ISBN 0870111892 ISBN 9780870111891

- Inoue, Masamichi S. 2007. Okinawa and the U.S. military: identity making in the Age of Globalization. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 9780231138901 ISBN 0231138903 ISBN 9780231511148 ISBN 0231511140

- Okinawa-ken Kyōiku Iinkai. 2000. The history and culture of Okinawa. Okinawa, Japan: The Board.

- Okinawa-ken (Japan). 1992. Keys to Okinawan culture. Okinawa, Japan: Okinawa Prefectural Government.

- Schrijvers, Peter. The GI War against Japan: American Soldiers in Asia and the Pacific during World War II. New York: New York University Press, 2002. ISBN 9780814798164.

- Sloan, Bill. 2007. The ultimate battle: Okinawa 1945—the last epic struggle of World War II. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 9780743292467 ISBN 0743292464

- Zabilka, Gladys. 1959. Customs and culture of Okinawa. [Tokyo]: Bridgeway Press.

External links

All links retrieved November 17, 2022.

- Okinawa Prefecture

- Okinawa Travel Information

- Okinawa 1988-1991 Blog, reporting news about Okinawa.

- Ryukyu Cultural Archives

| |||

| Cities | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Ginowan | Ishigaki | Itoman | Miyakojima | Nago | Naha (capital) | Nanjō | Okinawa | Tomigusuku | Urasoe | Uruma | |||

| Districts | |||

| Kunigami | Miyako | Nakagami | Shimajiri | Yaeyama | |||

| edit |

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

- Okinawa history

- Book_of_Sui history

- Okinawa_Monorail history

- Rail_transportation_in_Okinawa history

- Three_Non-nuclear_Principles history

- Gusuku history

- Southeast_Botanical_Gardens history

- Ryūkyū_Kingdom history

- Okinawan_cuisine history

- Battle_of_Okinawa history

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.