Omar N. Bradley

| Omar N. Bradley | |

|---|---|

| February 12, 1893 – April 8, 1981 (aged 88) | |

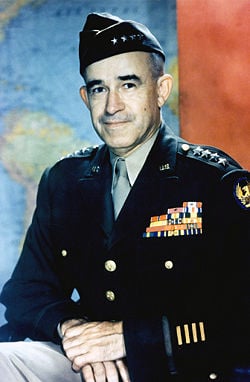

General Omar Bradley, United States Army, 1949 official photo | |

| Nickname | "The G.I.'s General" |

| Place of birth | Clark, Missouri, United States |

| Place of death | New York City, New York, United States |

| Allegiance | United States of America |

| Service/branch | U.S. Army |

| Years of service | 1915–1953 |

| Rank | General of the Army |

| Commands held | 82nd Infantry Division 28th Infantry Division U.S. II Corps First Army 12th Army Group Army Chief of Staff Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff |

| Battles/wars | Mexican Border Service World War I World War II Korea |

| Awards | Army Distinguished Service Medal Navy Distinguished Service Medal Silver Star Medal Legion of Merit Bronze Star Medal Knight Commander of the British Empire |

Omar Nelson Bradley KCB (February 12, 1893 – April 8, 1981) was one of the main U.S. Army field commanders in North Africa and Europe during World War II and a General of the Army in the United States Army. He was the last surviving five-star commissioned officer of the United States. He played a significant role in defeating the Axis Powers, liberating Paris, and pushing into Germany, where he was the first Allied commander to make contact with the Russians as they advanced from the East.

Bradley was the first official Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff and the first Chairman of the NATO Committee. Renowned for his tactical ability and for his rapport with his soldiers, who considered him to be a "soldier's soldier." In 1951, during the Korean War, he resisted Gen. Douglas MacArthur's demands to extend the war into enemy sanctuaries in Chinese territory. Comments made after World War II suggest that, as the arms race between the U.S. and the Soviet Union developed, Bradley was fearful that the emphasis on building yet more powerful ways of killing greater numbers of people was cheapening life. He spoke disapprovingly of a world that contained "nuclear giants and ethical infants." A world geared and ready for war may not value peace very highly.

Early life and career

Bradley, the son of a schoolteacher, John Smith Bradley, and his wife, Sarah Elizabeth "Bessie" Hubbard Bradley, was born into a poor family near Clark, Missouri. He attended Higbee Elementary School and graduated from Moberly High School. Bradley intended to enter the University of Missouri. Instead, he was advised to try for West Point. He placed first in his district placement exams and entered the academy in 1911.[1]

Bradley lettered in baseball three times, including on the 1914 team, where every player remaining in the army became a general. He graduated from West Point in 1915 as part of a class that contained many future generals, and which military historians have called, "The class the stars fell on." There were ultimately 59 generals in the graduating class, with Bradley and Dwight Eisenhower attaining the highest rank of General of the Army.

He joined the 14th Infantry Regiment, but like many of his peers, did not see action in Europe. Instead, he held a variety of stateside assignments. He served on the U.S.-Mexico border in 1915. When war was declared, he was promoted to captain, but was posted to the Butte, Montana, copper mines. He courted and later married Mary Elizabeth Quayle on December 28, 1916.[2] Bradley joined the 19th Infantry Division in August 1918, which was scheduled for European deployment, but the influenza pandemic and the armistice prevented it.

Between the wars, he taught and studied. From 1920–1924, he taught mathematics at West Point. He was promoted to major in 1924, and took the advanced infantry course at Fort Benning, Georgia. After a brief service in Hawaii, he studied at the Command and General Staff School at Fort Leavenworth in 1928–1929. From 1929, he taught at West Point again, taking a break to study at the Army War College in 1934. He was promoted to lieutenant colonel in 1936, and worked at the War Department directly under Army Chief of Staff George Marshall from 1938. In February 1941, he was promoted to brigadier general (bypassing the rank of colonel)[3] and sent to command Fort Benning (the first from his class to become a general officer). In February 1942, he took command of the 82nd Infantry Division before being switched to the 28th Infantry Division in June.

World War II

Bradley did not receive a frontline command until early 1943, after Operation Torch. He had been given VIII Corps but instead was sent to North Africa to serve as deputy to General George S. Patton. He succeeded Patton as head of II Corps in April, and directed it in the final Tunisian battles of April and May. He then led his corps, by then part of Patton's Seventh Army, onto Sicily in July.

In the approach to Normandy, Bradley was chosen to command the substantial U.S. First Army, which alongside the British Second Army made up General Montgomery's 21st Army Group. He embarked for Normandy from Portsmouth aboard the heavy cruiser USS ''Augusta'' (CA-31). During the bombardment on D-Day, Bradley positioned himself at a steel command cabin built for him on the deck of the Augusta, 20 feet (6 m) by 10 feet (3 m), the walls dominated by Michelin motoring maps of France, a few pin-ups, and large scale maps of Normandy. A row of clerks sat at typewriters along one wall, while Bradley and his personal staff clustered around the large plotting table in the center. Much of that morning, however, Bradley stood on the bridge, standing next to Task Force Commander Admiral Alan G. Kirk, observing the landings through binoculars, his ears plugged with cotton to muffle the blast of Augusta's guns.

On June 10, General Bradley and his staff left the Augusta to establish headquarters ashore. During Operation Overlord, he commanded three corps directed at the two American invasion targets, Utah Beach and Omaha Beach. Later in July, he planned Operation Cobra, the beginning of the breakout from the Normandy beachhead. As the build-up continued in Normandy, the U.S. Third Army was formed under Patton, Bradley's former commander, while General Hodges succeeded Bradley in command of the U.S. First Army; together they made up Bradley's new command, the 12th Army Group. By August, the 12th Army Group had swollen to over 900,000 men and ultimately consisted of four field armies. It was the largest group of American soldiers to ever serve under one field commander.

After the German attempt (Operation Lüttich) to split the U.S. armies at Mortain, Bradley's force was the southern half of an attempt to encircle the German Seventh Army and Fifth Panzer Army in Normandy, trapping them in the Chambois pocket (or Falaise pocket) (Operation Totalise). Although only partially successful, the German forces still suffered huge losses during their retreat.

The American forces reached the "Siegfried Line," or "Westwall," in late September. The sheer scale of the advance had taken the Allied high command by surprise. They had expected the German Wehrmacht to make stands on the natural defensive lines provided by the French rivers, and consequently, logistics had become a severe issue as well.

At this time, the Allied high command under General Eisenhower faced a decision on strategy. Bradley favored a strategy consisting of an advance into the Saarland, or possibly a two-thrust assault on both the Saarland and the Ruhr Area. Newly promoted to Field Marshal, Bernard Montgomery (British Army) argued for a narrow thrust across the Lower Rhine, preferably with all Allied ground forces under his personal command as they had been in the early months of the Normandy campaign, into the open country beyond and then to the northern flank into the Ruhr, thus avoiding the Siegfried Line. Although Montgomery was not permitted to launch an offensive on the scale he had wanted, George C. Marshall and Henry Arnold were eager to use the First Allied Airborne Army to cross the Rhine, so Eisenhower agreed to Operation Market-Garden. The debate, while not fissuring the Allied command, nevertheless led to a serious rift between the two Army group commanders of the European Theater of Operations. Bradley bitterly protested to Eisenhower the priority of supplies given to Montgomery, but Eisenhower, mindful of British public opinion, held Bradley's protests in check.

Bradley's Army Group now covered a very wide front in hilly country, from the Netherlands to Lorraine and, despite his being the largest Allied Army Group, there were difficulties in prosecuting a successful broad-front offensive in difficult country with a skilled enemy that was recovering its balance. Courtney Hodges' 1st Army hit difficulties in the Aachen Gap and the Battle of Hurtgen Forest cost 24,000 casualties. Further south, Patton's 3rd Army lost momentum as German resistance stiffened around Metz's extensive defenses. While Bradley focused on these two campaigns, the Germans had assembled troops and materiel for a surprise offensive.

Bradley's command took the initial brunt of what would become the Battle of the Bulge. Over Bradley's protests, for logistical reasons the 1st Army was once again placed under the temporary command of Montgomery's Twenty-First Army Group. In a move without precedent in modern warfare, the U.S. 3rd Army under George Patton disengaged from their combat in the Saarland, moved 90 miles (145 km) to the battlefront, and attacked the Germans' southern flank to break the encirclement at Bastogne. In his 2003 biography of Eisenhower, Carlo d'Este implies that Bradley's subsequent promotion to full general was to compensate him for the way in which he had been sidelined during the Battle of the Bulge.

Bradley used the advantage gained in March 1945—after Eisenhower authorized a difficult but successful Allied offensive (Operation Veritable and Operation Grenade) in February 1945—to break the German defenses and cross the Rhine into the industrial heartland of the Ruhr. Aggressive pursuit of the disintegrating German troops by Bradley's forces resulted in the capture of a bridge across the River Rhine at Remagen. Bradley and his subordinates quickly exploited the crossing, forming the southern arm of an enormous pincer movement encircling the German forces in the Ruhr from the north and south. Over 300,000 prisoners were taken. American forces then met up with the Soviet forces near the River Elbe in mid-April. By V-E Day, the 12th Army Group was a force of four armies (1st, 3rd, 9th, and 15th) that numbered over 1.3 million men.[4]

Post-war

Bradley headed the Veterans Administration for two years after the war. He is credited with doing much to improve its health care system and with helping veterans receive their educational benefits under the G. I. Bill of Rights.[5] He was made Army Chief of Staff in 1948 and first official Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff in 1949.[6] On September 22, 1950, he was promoted to the rank of General of the Army, the fifth—and last—man in the twentieth century to achieve that rank. Also in 1950 he was made the first Chairman of the NATO Committee. He remained on the committee until August 1953 when he left active duty to take a number of positions in commercial life. One of those positions was Chairman of the Board of the Bulova Watch Company from 1958 to 1973.[7]

As Chairman of the Joint Chiefs, Bradley strongly rebuked Gen. Douglas MacArthur, the commander of the U.N. forces in Korea, for his desire to expand the Korean War into China by attacking enemy sanctuaries.[8] Soon after President Truman relieved MacArthur of command in April 1951, Bradley said in congressional testimony, "Red China is not the powerful nation seeking to dominate the world. Frankly, in the opinion of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, this strategy would involve us in "the wrong war, at the wrong place, at the wrong time, and with the wrong enemy."

He published his memoirs in 1951, as A Soldier's Story, and took the opportunity to attack Field Marshal Montgomery's 1945 claims to have won the Battle of the Bulge. Bradley spent his last years at a special residence on the grounds of the William Beaumont Army Medical Center, part of the complex which supports Fort Bliss, Texas.[9]

On December 1, 1965, Bradley's wife Mary died of leukemia. He met Esther Dora "Kitty" Buhler while doing business for Bulova, and married her on September 12, 1966[10]. Together they established the Omar N. Bradley Foundation and the Omar N. Bradley Library at West Point in 1974. Pres. Gerald R. Ford awarded Bradley the Presidential Medal of Freedom on Januaary 10, 1977.

In 1970 Bradley also served as a consultant during the making of the film Academy Award winning film, Patton. The film, in which Bradley is portrayed by actor Karl Malden, is very much seen through Bradley's eyes: whilst admiring of Patton's aggression and will to victory, the film is also implicitly critical of Patton's egotism (particularly his alleged indifference to casualties during the Sicilian campaign) and love of war for its own sake. Bradley is shown being praised by a German intelligence officer for his lack of pretentiousness, "unusual in a general."

One of his last public appearances was in connection with the inauguration of President Ronald Reagan in January 1981. Upon Bradley's death, he was buried with full military honors at Arlington National Cemetery. He is buried next to his two wives.[11]

Legacy

Unlike some of the more colorful generals of World War II, Bradley was a polite and courteous man. He was popular with both his superiors and his men, earning the esteem and confidence of both in effect. First favorably brought to public attention by correspondent Ernie Pyle, he was informally known as "the soldier's general." Will Lang, Jr. of LIFE magazine said, "The thing I most admire about Omar Bradley is his gentleness. He was never known to issue an order to anybody of any rank without saying 'Please' first."

Bradley is known for saying, "Ours is a world of nuclear giants and ethical infants. We know more about war than about peace, more about killing than we know about living."

The U.S. Army's M2 Bradley infantry fighting vehicle and M3 Bradley cavalry fighting vehicle are named after General Bradley.

On May 5, 2000, the United States Postal Service issued Distinguished Soldiers stamps in which Bradley was honored.[12]

Bradley also served as a member of Pres. Lyndon Johnson's "Wise Men," a think-tank comprised of well-known Americans considered experts in their fields. Their main purpose was to recommend strategies for dealing with the nation's problems, including the Vietnam War. While agreeing with the war in principle, Bradley believed it was being micromanaged by politicians and Pentagon bureaucrats.

Summary of service

Dates of rank

- Graduated from the United States Military Academy—Class of 1915, 44th of 164

- Second Lieutenant, United States Army: June 12 1915

- First Lieutenant, United States Army: October 13 1916

- Captain, United States Army: August 22 1917

- Major, National Army: July 17 1918

- Captain, Regular Army (reverted to peacetime rank): November 4 1922

- Major, Regular Army: June 27 1924

- Lieutenant Colonel, Regular Army: July 22 1936

- Brigadier General (Temporary), Regular Army: February 24 1941

- Major General, Army of the United States: February 18 1942

- Lieutenant General, Army of the United States: June 9 1943

- Promoted to permanent rank of Colonel in the Regular Army: November 13 1943

- General, Army of the United States: March 29 1945

- Appointed a General in the Regular Army: January 31 1949

- General of the Army: September 22 1950

Primary decorations

- Army Distinguished Service Medal (With three oak leaf clusters)

- Navy Distinguished Service Medal

- Silver Star

- Legion of Merit (w/oak leaf cluster)

- Bronze Star Medal

- Mexican Border Service Medal

- World War I Victory Medal

- American Defense Service Medal

- European-African-Middle Eastern Campaign Medal

- World War II Victory Medal

- Army of Occupation Medal

- National Defense Service Medal

and also

- Presidential Medal of Honor 1977

Assignment history

- 1911: Cadet, United States Military Academy

- 1915: 14th Infantry Regiment

- 1919: ROTC professor, South Dakota State College

- 1920: Instructor, United States Military Academy (West Point)

- 1924: Infantry School Student, Fort Benning, Georgia

- 1925: Commanding Officer, 19th and 27th Infantry Regiments

- 1927: Office of National Guard and Reserve Affairs, Hawaiian Department

- 1928: Student, Command and General Staff School

- 1929: Instructor, Fort Benning, Infantry School

- 1934: Plans and Training Office, USMA West Point

- 1938: War Department General Staff, G-1 Chief of Operations Branch and Assistant Secretary of the General Staff

- 1941: Commandant, Infantry School Fort Benning

- 1942: Commanding General, 82nd Infantry Division and 28th Infantry Division

- 1943: Commanding General, II Corps, North Africa and Sicily

- 1943: Commanding General, Field Forces European Theater

- 1944: Commanding General, First Army (Later 1st and 12th U.S. Army Groups)

- 1945: Administrator of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Administration

- 1948: United States Army Chief of Staff

- 1949: Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff

- 1953: Retired from active service

Notes

- ↑ Omar N. Bradley and Clay Blair. A General's Life: An Autobiography. (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1983), 18-19.

- ↑ Bradley, General's Life, 42.

- ↑ Jay Hollister, General Omar Nelson Bradley. Retrieved May 14, 2007.

- ↑ Bradley, General's Life, 117-436.

- ↑ Bradley, General's Life, 447-448.

- ↑ Bradley, General's Life, 447-448.

- ↑ Bulova, The History of Bulova. Retrieved May 14, 2007.

- ↑ Bradley, General's Life, 638.

- ↑ Omar N. Bradley, A Soldier's Story (New York: Holt, 1951).

- ↑ Bradley, General's Life, 666-667.

- ↑ Bradley, General's Life, 670.

- ↑ United States Postal Service, Distinguished Soldiers Retrieved May 16, 2007.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Bradley, Omar N. A Soldier's Story. New York: Holt, 1951. ISBN 0375754210

- Bradley, Omar N. and Clay Blair. A General's Life: An Autobiography. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1983. ISBN 0671410237

- Bulova. About Bulova, The History of Bulova Retrieved May 14, 2007.

- D'Este, Carlo. Eisenhower: A Soldier's Life. Holt Paperbacks, 2003. ISBN 0805056874

- Greenwell, Dale. The Greatest American Who Ever Lived A World War II Album, Selected from Omar N. Bradley's Photographs, the John Mladinich Collection. Biloxi, MS: JJ Co, 2004 ISBN 9780975987209

- Hollister, Jay. General Omar Nelson Bradley. General Omar Nelson Bradley. Retrieved May 14, 2007.

- Reeder, Red. Omar Nelson Bradley: The Soldiers' General, Illustrated by Herman B. Vestal. Champaign, IL: Garrard Pub. Co., 1969.

- United States Postal Service. Distinguished Soldiers Stamps. Distinguished Soldiers. Retrieved May 16, 2007.

External links

All links retrieved November 17, 2022.

- Bradley's biography at the U.S. Army website.

- Omar Nelson Bradley, General of the Army, Arlington National Cemetery profile.

| Preceded by: Gen. Dwight Eisenhower |

Chief of Staff of the United States Army 1948–1949 |

Succeeded by: Gen. J. Lawton Collins |

| Preceded by: Adm. William D. Leahy as Chief of Staff to the Commander in Chief |

Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff 1949–1953 |

Succeeded by: Adm. Arthur W. Radford |

| Preceded by: Billy Graham |

Sylvanus Thayer Award recipient 1973 |

Succeeded by: Robert Daniel Murphy |

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.