Otto Hahn

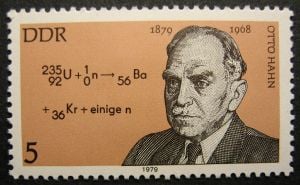

Otto Hahn (March 8, 1879 ‚Äď July 28, 1968) was a German chemist and a pioneer of radioactivity and radiochemistry. He received the 1944 Nobel Prize in Chemistry. He was called the "founder of the atomic age" by his contemporaries and, officially, by the senate and scientists of the Max Planck Society. Glenn T. Seaborg, also a Nobel laureate in Chemistry and President of the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission, regarded him as "the father of nuclear chemistry."

Biography

Childhood

Otto Hahn was born on March 8, 1879, in Frankfurt am Main, the youngest son of the glazier and entrepreneur Heinrich Hahn (1845-1922) ("Glasbau Hahn") and his wife Charlotte Hahn, née Giese (1845-1905). Together with his brothers Karl, Heiner and Julius, he enjoyed a sheltered childhood. At the age of 15, he began to take a special interest in chemistry and carried out simple experiments in the laundry room. His father Heinrich, who became prosperous thanks to his hard work and thrift, and the originality of his ideas, would have liked Otto Hahn to study architecture, as he had built or acquired several residential and business properties. But his son Otto succeeded in persuading him that his ambition was to become an industrial chemist.

Education

In 1897, after taking his Abitur at the Klinger Oberrealschule in Frankfurt, Hahn begun to study chemistry and mineralogy at the University of Marburg. His subsidiary subjects were physics and philosophy. Here, Hahn joined the Students' Association of Natural Sciences and Medicine, which was a student fraternity and a forerunner of today's Nibelungia Fraternity. He spent his third and fourth semester studying under Adolf von Baeyer at the University of Munich. In 1901, Hahn received his doctorate in Marburg for a dissertation entitled On Bromine Derivates of Isoeugenol, a topic from the field of classical organic chemistry. After completing his one-year military service, the young chemist returned to the University of Marburg, where for two years he worked as assistant to his doctoral supervisor, Geheimrat Professor Theodor Zincke.

Early research

Hahn's intention was to work in industry. With this in mind, and also to improve his knowledge of English, he took up a post at University College London in 1904, working under Sir William Ramsay, famous for his discovery of inert gases. Here Hahn worked on radiochemistry, which at that time was still a relatively new field. In 1905, in the course of his work with salts of the element radium, Hahn discovered a substance he called radiothorium (thorium 228), which at that time was believed to be a new radioactive element. (In fact, it was a still undiscovered isotope of the known element thorium. The terms "isotopy" and "isotope" were only coined in 1913, by the British chemist Frederick Soddy). In the autumn of 1905, Hahn transferred to McGill University in Montreal, Canada, in order to pursue further research under Sir Ernest Rutherford. It was here that Hahn discovered the new radioactive elements thorium C, radium D and radioactinium (as he termed them).

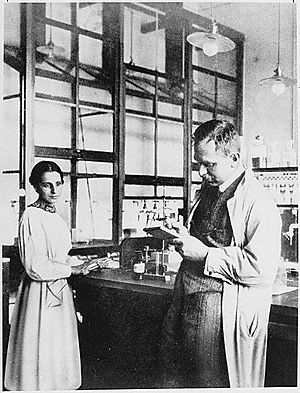

In the summer of 1906 Hahn returned to Germany, where he collaborated with Emil Fischer at the University of Berlin. Fischer placed at his disposal a former woodworking shop in the Chemical Institute to use as his own laboratory ("Holzwerkstatt"). There, in the space of a few months, using extremely primitive apparatus, Hahn discovered mesothorium I, mesothorium II and‚ÄĒindependently from Boltwood‚ÄĒthe mother substance of radium, ionium. In subsequent years, mesothorium I (radium 228) assumed great importance because, like radium 226 (discovered by Pierre and Marie Curie), it was ideally suited for use in medical radiation treatment, while costing only half as much to manufacture. (In 1914, for the discovery of mesothorium I, Otto Hahn was first nominated for the Nobel Prize in Chemistry by Adolf von Baeyer). In June 1907, by means of the traditional habilitation thesis, Hahn qualified to teach at the University of Berlin. On September 28, 1907‚ÄĒsomething of a historic date in the history of atomic research‚ÄĒhe made the acquaintance of the young Austrian physicist Lise Meitner, who had transferred from Vienna to Berlin. So began the thirty-year collaboration and lifelong close friendship between the two scientists.

After the physicist Harriet Brooks had observed a radioactive recoil in 1904, but interpreted it wrongly, Otto Hahn succeeded, in the winter of 1908/09, in demonstrating the radioactive recoil in the alpha transformation and interpreting it correctly. "… a profoundly significant discovery in physics with far-reaching consequences", as the physicist Walther Gerlach put it.

In 1910 Hahn was appointed professor, and in 1912 he became head of the Radioactivity Department of the newly founded "Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Chemistry" in Berlin-Dahlem (since 1956 "Otto Hahn Building of the Free University," Berlin, Thielallee 63). Succeeding Alfred Stock, Hahn was Director of the Institute from 1928 to 1946. As early as 1924, Hahn was elected to full membership of the Prussian Academy of Sciences in Berlin (proposed by Einstein, Planck, Fritz Haber, Schlenk and von Laue).

In June 1911, while attending a conference in Stettin (today: Szczecin, Poland) Otto Hahn met the young and highly sensitive art student Edith Junghans (1887-1968). On March 22, 1913 the couple married in Edith's native city of Stettin, where her father, Paul Ferdinand Junghans, was a high-ranking law officer and until his early death in 1915 was President of the City Parliament. On April 9, 1922 the couple had their only son, Hanno, who would become a distinguished art historian and architectural researcher (at the Hertziana in Rome). In 1960, while on a study trip in France, Dr Hanno Hahn was involved in a fatal car accident, together with his wife and assistant Ilse Hahn, née Pletz. They left a fourteen-year-old son, Dietrich. (In 1990, in memory of Hanno and Ilse Hahn and in support of talented young art historians, the internationally respected "Hanno and Ilse Hahn Prize for Outstanding Contributions to Italian Art History" was established. It is awarded biennally by the Bibliotheca Hertziana, Max Planck Institute for Art History, in Rome).

During the First World War, Hahn was conscripted into the army, where he was assigned, together with James Franck and Gustav Hertz, to the special unit for chemical warfare under the direction of Fritz Haber. The unit developed, tested and produced poison gas for military purposes, and was sent to both the western and eastern front lines. In December 1916, Hahn was transferred to the "Headquarter of His Majesty" in Berlin, and was able to resume his radiochemical research in his institute. In 1917/18 Hahn and Lise Meitner isolated a long-lived activity, which they named "proto-actinium." Already in 1913, Fajans and Göhring had isolated a short-lived activity from uranium X2 and called the substance "brevium." The two activities were different isotopes of the same undiscovered element no. 91. Finally in 1949, the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) named this new element protactinium and confirmed Hahn and Meitner as discoverers.

In February 1921, Otto Hahn published the first report on his discovery of uranium Z, the first example of nuclear isomerism. "… a discovery that was not understood at the time but later became highly significant for nuclear physics", as Walther Gerlach remarked. And, indeed, it was not until 1936 that the young physicist Carl Friedrich von Weizsäcker succeeded in providing a theoretical explanation of the phenomenon of nuclear isomerism. For this discovery, whose full significance was recognized by very few, Hahn was again proposed, in 1923, for the Nobel Prize in Chemistry, this time by Max Planck, among others.

In the early 1920s, Otto Hahn created a new field of work. Using the "emanation method," which he had recently developed, and the "emanation ability," he founded what became known as "Applied Radiochemistry" for the researching of general chemical and physical-chemical questions. In 1933 he published a book in English (and later in Russian) entitled "Applied Radiochemistry." It contains the lectures given by Hahn when he was a visiting professor at Cornell University in Ithaca, New York in 1933. "As a young graduate student at the University of California at Berkeley in the mid-1930s and in connection with our work with plutonium a few years later, I used his book "Applied Radiochemistry" as my bible. This book was based on a series of lectures which Professor Hahn had given at Cornell in 1933; it set forth the "laws" for the co-precipitation of minute quantities of radioactive materials when insoluble substances were precipitated from aqueous solutions. I recall reading and rereading every word in these laws of co-precipitation many times, attempting to derive every possible bit of guidance for our work, and perhaps in my zealousness reading into them more than the master himself had intended. I doubt that I have read sections in any other book more carefully or more frequently than those in Hahn's "Applied Radiochemistry." In fact, I read the entire volume repeatedly and I recall that my chief disappointment with it was its length. It was too short." These were the words of Glenn T. Seaborg, President of the United States Atomic Energy Commission, in 1966.

The discovery of nuclear fission

Jointly with Lise Meitner and his pupil and assistant Fritz Strassmann (1902-1980), Otto Hahn continued the research work that the Italian physicist Enrico Fermi and his team had started in 1934 when they bombarded uranium with neutrons. Until 1938 all scientists believed that the elements with atomic numbers greater than 92 (which are known as transuranium elements) arise when uranium atoms are bombarded with neutrons.

On July 13, 1938, with the preparatory help and support of Hahn, Lise Meitner emigrated illegally via Holland to Stockholm, Sweden, as she had lost her Austrian citizenship after the annexation of Austria to Nazi Germany in March 1938, and as she was of Jewish origin she was particularly at risk.

Otto Hahn continued the work with Fritz Strassmann on elucidating the outcome of the bombardment of uranium with thermal neutrons. Prompted by a letter from Meitner, in December 1938 Hahn and Strassmann looked for barium in the alleged transuranium elements produced by bombarding an uranium sample with neutrons, and confirmed its presence. The barium was detected by the use of an organic barium salt constructed by Wilhelm Traube, a Jewish chemist who was later arrested and murdered despite Hahn's efforts to save him.

On the evidence of the decisive experiment on December 17, 1938 (the celebrated "radium-barium-mesothorium-fractionation"), Otto Hahn concluded that the uranium nucleus had "burst" into atomic nuclei of medium weight. This was the discovery of nuclear fission.

Hahn's and Strassmann's radiochemical findings were first published on January 6, 1939. One day later, February 11, 1939 (Otto Hahn having previously informed his colleague of his chemical experiments by letter) Lise Meitner and her nephew, the physicist Otto Robert Frisch, who had also emigrated to Sweden, published the first physical-theoretical explanation of nuclear fission in the English journal "Nature." This was when Frisch coined the term "nuclear fission," which subsequently became internationally known.

"The discovery of nuclear fission by Otto Hahn and Fritz Strassmann opened up a new era in human history. During the war, Otto Hahn - together with his pupils - worked on uranium fission reactions. By 1945 he had drawn up a list of 25 elements and about 100 isotopes whose existence he had demonstrated. - Thanks to his determined intervention, Otto Hahn, who had always been an opponent of the Nazi dictatorship, was able to support numerous members of his institute whose lives were in danger or were suffering persecution, and prevent them from being sent to the front line or deported. In this, he was assisted by his courageous wife Edith, who had for years collected food and groceries for Jewish people hiding in Berlin. As early as 1934, Hahn resigned from the University of Berlin in protest against the dismissal of Jewish colleagues, notably Lise Meitner, Fritz Haber and James Franck.

At the end of World War II in 1945 Hahn was suspected of working on the German nuclear energy project to develop an atomic reactor or an atomic bomb (But his only connection was the discovery of fission; he did not work on the program). Hahn and his colleagues were interned at Farm Hall, Godmanchester, near Cambridge, England. While they were there, the German scientists learned of the dropping of the American atom bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki on August 6 and August 9. Otto Hahn was on the brink of despair, as he felt that because he had discovered nuclear fission he shared responsibility for the death and suffering of hundreds of thousands of Japanese people. Early in January 1946, the group was allowed to return to Germany.

The Nobel Prize in Chemistry

In November 1945 the Royal Swedish Academy awarded Hahn the 1944 Nobel Prize in Chemistry

"There is no doubt at all that Hahn fully deserves the Nobel Prize in Chemistry" wrote Lise Meitner to her friend Eva von Bahr-Bergius in late 1945. However, this statement may be seen as Meitner's expressing her years-long admiration for Hahn as a fellow scientist and especially as a great chemist and thus deserving of a Nobel for any of his major accomplishments in the field of Chemistry. It does not deflect from her belief that the discovery of fission was more related to physics than to chemistry, nor to her belief that she deserved the Nobel herself or even her opinion that Hahn should have shared the prize with her.

Founder of the Max Planck Society

From 1948 to 1960, Otto Hahn was the founding President of the newly formed Max Planck Society for the Advancement of Science. Through his tireless activity and worldwide respect, it succeeded in regaining the renown once enjoyed by the Kaiser Wilhelm Society. Immediately after the Second World War, Hahn reacted to the dropping of the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki by coming out strongly against the use of nuclear energy for military purposes. He saw the application of his scientific discoveries to such ends as a misuse, or even a crime. Consequently, among other things, he initiated the Mainau Declaration of 1955, in which a large number of Nobel Prize-winners called attention to the dangers of atomic weapons and warned the nations of the world urgently against the use of "force as a final resort."

He was also instrumental and one of the authors of the Göttingen Declaration of 1957, in which, together with 17 leading German atomic scientists, he protested against the nuclear arming of the new German armed forces (Bundeswehr). In January 1958, Otto Hahn signed the Pauling Appeal to the United Nations for the "immediate conclusion of an international agreement to stop the testing of nuclear weapons," and in October he signed the international Agreement to call a meeting to draw up a world constitution. Right up to his death, he never tired of warning urgently of the dangers of the nuclear arms race between the great powers and of the radioactive contamination of the planet. From 1957, Otto Hahn was repeatedly proposed by international organizations, including the largest French trade union CGT, for the Nobel Peace Prize. Linus Pauling, winner of the Nobel Peace Prize in 1962, once described Otto Hahn as "an inspiration to me."

Acknowledgments and awards

Hahn received many governmental honors and academic awards from all over the world. He was elected member or honorary member in 45 Academies and scientific societies (among them the Royal Society in London and the Academies in Allahabad (India), Bangalore (India), Boston (USA), Bucharest, Copenhagen, Helsinki, Lisbon, Madrid, Rome, Stockholm, Vienna) and received 37 of the highest national and international orders and medals (among them the Golden Paracelsus Medal from the Swiss Chemical Society and the Faraday Medal from the British Chemical Society). In 1959, President Charles de Gaulle of France made him an Officer of the Légion d'Honneur, he was made a knight of the Peace Class of the Order Pour le Mérite, received the Distinguished Service Order and the Grand Cross of the Federal Republic of Germany. In 1961 Pope John XXIII awarded him the Gold Medal of the Papal Academy. (In 1957 Hahn was elected an honorary citizen of the city of Magdeburg, German Democratic Republic, and in 1958 an honorary member of the Soviet Academy of Sciences in Moscow. He declined both honors).

In 1966, US President Lyndon B. Johnson and the US Atomic Energy Commission in Washington D.C. awarded Otto Hahn the Enrico Fermi Prize (together with Lise Meitner and Fritz Strassmann). This was the only time that foreign scientists were honored with this award.

Otto Hahn, honorary citizen of the cities of Frankfurt am Main and Göttingen and the land and the city of Berlin, died at July, 28th, 1968 in Göttingen. The next day, the Max Planck Society published the following obituary notice in all the major newspapers: "On July 28, in his 90th year, our Honorary President Otto Hahn passed away. His name will be recorded in the history of humanity as the founder of the atomic age. In him Germany and the world have lost a scholar who was distinguished in equal measure by his integrity and personal humility. The Max Planck Society mourns its founder, who continued the tasks and traditions of the Kaiser Wilhelm Society after the war, and mourns also a good and much loved human being, who will live in the memories of all who had the chance to meet him. His work will continue. We remember him with deep gratitude and admiration."

Commemorative honors

Proposals were made at different times, first in 1971 by American chemists, that the newly synthesized element no. 105 should be named Hahnium in Hahn's honor, although in 1997 the IUPAC (International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry) finally named it Dubnium, after the Russian research center in Dubna (see Element naming controversy). The intention is, however, that element no. 108, Hassium should be renamed Hahnium in the future. In addition, in 1964 the only European and one of the world's three nuclear-powered civilian ships, the freighter NS Otto Hahn, was named in his honor. In 1959 there were the opening ceremonies of the "Otto Hahn Institute" in Mainz and the "Hahn Meitner Institute for Nuclear Research (HMI)" in Berlin. There are craters on Mars and moon, and the asteroid No. 19126 "Ottohahn" named in his honor, as well as the "Otto Hahn Prize" of both the German Chemical and Physical Societies, the "Otto Hahn Medal" of the Max Planck Society and the "Otto Hahn Peace Medal in Gold" of the United Nations Association of Germany (DGVN) in Berlin.

Many cities and districts in German-speaking countries have named secondary schools after him, and countless streets, squares and bridges throughout Europe bear his name. Several states have honored Otto Hahn by issuing coins, medals, and stamps‚ÄĒamong them, the Federal Republic of Germany, the German Democratic Republic, Austria, Romania, Angola, Cuba, the Commonwealth of Dominica, Madagascar, St. Vincent & the Grenadines, Chad, Guinea and Bissau). An island in the Antarctic (near Mount Discovery) was also named after him, as were two Intercity trains of the German Federal Railways in 1971, running between Hamburg and Basel SBB, and the "Otto Hahn Library" in G√∂ttingen. In 1974, in appreciation of the special contribution of Otto Hahn to German-Israeli relations, a wing of the Weizmann Institute of Science in Rehovot, Israel, was given the name "Otto Hahn Wing." In several cities and districts busts, monuments and memorial plaques were unveiled, including Berlin (East and West), Boston (USA), Frankfurt am Main, G√∂ttingen, Gundersheim, Mainz, Marburg, Munich (in the hall of honor in the Deutsches Museum), Rehovot (Israel), San Vigilio (Lake Garda) and Vienna (in the foyer of the International Atomic Energy Agency, IAEA). A special honor in 1997 was conferred on Hahn in the Netherlands: after an azalea already bore his name (rhododendron luteum Otto Hahn), Dutch rose growers named a new variety of rose "Otto Hahn."

At the end of 1999, the German newsmagazine FOCUS published an inquiry of 500 leading natural scientists, engineers and physicians about the most important scientists of the twentieth century. In this poll the experimental chemist Otto Hahn - after the theoretical physicists Albert Einstein and Max Planck - was elected third (with 81 points) and thus the most significant experimental researcher of his time. (FOCUS, 52, (1999): 103-108).

Publications by Hahn

- Hahn, Otto. 1936. Applied Radiochemistry. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Hahn, Otto, W. Gaade ed. 1950. New Atoms - Progress and some memories. New York, NY: Elsevier Inc.

- Hahn, Otto, Willy Ley ed. 1966. A Scientific Autobiography. New York, NY: Charles Scribner's Sons.

- Hahn, Otto, Ernst Kaiser and Eithne Wilkins trans. 1970. My Life. London, UK: Macdonald & Co. ISBN 0356029336.

See also

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Asimov, Isaac. 1982. Asimov's Biographical Encyclopedia of Science and Technology, 2nd ed. Garden City, NY: Doubleday. ISBN 0385177712.

- Fermi, Laura. 1962. The Story of Atomic Energy. New York, NY: Random House.

- Berninger, Ernst H. 1970. Otto Hahn 1879-1968. (English edition) Bonn, DE: Inter Nationes. ISBN 3804707572.

- Reid, R.W. 1969. Tongues of Conscience. London, UK: Constable & Co. ISBN 0094558906.

- Spence, Robert. 1970. Otto Hahn - Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society, Volume 16. London.

- Graetzer, Hans D., David L. Anderson. 1971. The Discovery of Nuclear Fission. A documentary history. New York, NY: Van Nostrand-Reinhold.

- Seaborg, Glenn T. 1972. Nuclear Milestones. San Francisco, CA: W.H. Freeman. ISBN 0716703424.

- Beyerchen, Alan D. 1977. Scientists under Hitler. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 0300018304.

- Nachmansohn, David. 1979. German-Jewish Pioneers in Science 1900-1933. Highlights in Atomic Physics, Chemistry and Biochemistry. New York, NY: Springer Inc. ISBN 0387904026.

- Feldman, Anthony, Peter Ford. 1986. Otto Hahn - in: Scientists and Inventors. New York, NY: Facts on File. ISBN 0871964104.

- Clark, Ronald W. 1980. The Greatest Power on Earth. London, UK: Sidgwick & Jackson. ISBN 0283987154.

- Shea, William R. ed. 1983. Otto Hahn and the Rise of Nuclear Physics. Boston, MA: D. Reidel Pub. Co. ISBN 902771584X.

- McKay, Alwyn. 1984. The Making of the Atomic Age. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. ISBN 019289174X.

- Rhodes, Richard. 1988. The Making of the Atomic Bomb. New York, NY: Simon and Schuster. ISBN 0671441337.

- Revill, J.A., Charles Frank ed. 1993. Operation Epsilon. The Farmhall Transcripts. Philadelphia, PA: IOP Publishing. ISBN 0750302747.

- Hoffmann, Klaus. 2001. Otto Hahn - Achievement and Responsibility. New York, NY: Springer Inc. ISBN 0387950575.

- Kant, Horst. 2002. Otto Hahn and the Declarations of Mainau and Göttingen. New York, NY: Springer. ISBN 0387950575.

- Whiting, Jim. 2004. Otto Hahn and the Discovery of Nuclear Fission. Bear, DE: Mitchell Lane Publishers. ISBN 1584152044.

|

1926:¬†Theodor Svedberg | 1927:¬†Heinrich Wieland | 1928:¬†Adolf Windaus | 1929:¬†Arthur Harden / Hans von Euler-Chelpin | 1930:¬†Hans Fischer | 1931:¬†Carl Bosch / Friedrich Bergius | 1932:¬†Irving Langmuir | 1934:¬†Harold Urey | 1935:¬†Fr√©d√©ric Joliot-Curie / Ir√®ne Joliot-Curie | 1936:¬†Peter Debye | 1937:¬†Norman Haworth / Paul Karrer | 1938:¬†Richard Kuhn | 1939:¬†Adolf Butenandt / Leopold RuŇĺińćka | 1943:¬†George de Hevesy | 1944:¬†Otto Hahn | 1945:¬†Artturi Virtanen | 1946:¬†James B. Sumner / John Northrop / Wendell Meredith Stanley | 1947:¬†Robert Robinson | 1948:¬†Arne Tiselius | 1949:¬†William Giauque | 1950:¬†Otto Diels / Kurt Alder |

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.