| War |

| History of war |

| Types of War |

| Civil war · Total war |

| Battlespace |

| Air · Information · Land · Sea · Space |

| Theaters |

| Arctic · Cyberspace · Desert Jungle · Mountain · Urban |

| Weapons |

| Armored · Artillery · Biological · Cavalry Chemical · Electronic · Infantry · Mechanized · Nuclear · Psychological Radiological · Submarine |

| Tactics |

|

Amphibious · Asymmetric · Attrition |

| Organization |

|

Chain of command · Formations |

| Logistics |

|

Equipment · Materiel · Supply line |

| Law |

|

Court-martial · Laws of war · Occupation |

| Government and politics |

|

Conscription · Coup d'état |

| Military studies |

|

Military science · Philosophy of war |

A prisoner of war (POW) is a combatant who is imprisoned by an enemy power during or immediately after an armed conflict or war. International law defines who qualifies as a prisoner of war as persons captured while fighting in the military. Rules on the treatment of prisoners of war extend only to combatants, excluding civilians who engage in hostilities (who are defined by international law as war criminals) and forces that do not observe conventional requirements for combatants as defined in laws of war.

In the history of war (which covers basically all of human history) attitudes toward enemy combatants who were captured has changed. In the most violent times, no prisoners were taken—all enemy combatants were killed during and even after they ceased to fight. For most of human history, however, combatants of the losing side and, on many occasions, their civilians also were captured and kept or sold as slaves. While the concept of prisoner of war and their rights emerged in the seventeenth century, it was not until the beginning of the twentieth century that these rights began to be specified and an international definition attempted.

The Geneva Conventions of 1929 and 1949 finally set the standards for definition and treatment of prisoners of war. While not all countries have been willing or able to abide by these rules on all occasions, nonetheless the existence of the standards of treatment that are expected of other human beings, formally considered to be enemies, is a great advance for humankind. Until all societies can learn to live in peace and harmony, humane treatment of those who were involved in violent conflict but have capitulated or been rendered harmless, is a step toward reconciliation and forgiveness.

Definition

To be entitled to prisoner of war status, the captured service member must have conducted operations according to the laws and customs of war: be part of a chain of command and wear a uniform and bear arms openly. Thus, franc-tireurs, terrorists, and spies may be excluded. In practice, these criteria are not always interpreted strictly. Guerrillas, for example, may not wear a uniform or carry arms openly yet are typically granted POW status if captured. However, guerrillas or any other combatant may not be granted the status if they try to use both the civilian and the military status. Thus, the importance of uniforms — or as in the guerrilla case, a badge — to keep this important rule of warfare.

Alternative definitions

Some groups define prisoner of war in accordance with their internal politics and world view. Since the special rights of a prisoner of war, granted by governments, are the result of multilateral treaties, these definitions have no legal effect and those claiming rights under these definitions would legally be considered common criminals under an arresting jurisdiction's laws. However, in most cases these groups do not demand such rights.

The United States Army uses the term prisoner of war to describe only friendly soldiers who have been captured. The proper term for enemy prisoners captured by friendly forces is Enemy Prisoner of War or EPW.[1]

Hague Convention

The Hague Convention of 1907 was a preliminary effort to establish an international definition of POW status.[2] This convention states that

- Prisoners are in the power of the hostile capturing government, not the actual captors; and must be treated humanely and that their belongings remain theirs (with the exception of arms, horses, and military papers)

- Prisoners may be interned in a town, fortress, or other similar facility but cannot be confined unless absolutely vital to public safety

- The capturing state may put prisoners to work, but not for the war effort and must pay wages to the prisoner upon their release

- The capturing government is responsible for the well-being of prisoners and barring some other agreement must house and board prisoners to the same standards as their own soldiers

- Relief societies for prisoners of war must have access to the prisoners

- Prisoners must be able to contact representatives from their states

- Prisoners are bound by the laws of their captor state

The Geneva Convention

The Geneva Conventions of 1929 and 1949 attempted to further define the status and treatment of prisoners of war.[3] The Geneva Convention defines those who can be considered POWs, including members of a foreign nation's army, a hostile militia member, members of an army raised by a nation not recognized by the detaining state, civilians with combat-support roles, and civilians who take up arms. This convention also stipulates that those defined as POWs must be afforded every right of a POW from the time they are captured until their repatriation.

History

Ancient times

For most of human history, depending on the temperament of the victors, combatants of the losing side in a battle could expect to be either slaughtered, to eliminate them as a future threat, or enslaved, bringing economic and social benefits to the victorious side and its soldiers. Typically, little distinction was made between combatants and civilians, although women and children were more likely to be spared, if only to be raped or captured for use or sale as slaves. Castration was common in Ancient Greece, and remained in practice in Chinese dynasties until the late nineteenth century.

Middle Ages

During the Middle Ages, religious wars were particularly ferocious. It was during the seventh century that Islamic concept of Ma malakat aymanukum was introduced in the Divine Islamic laws of the Qur'an, where female slaves obtained by war or armed conflicts were defined as the only persons to be used for sexual purposes.

During this time, extermination of heretics or "non-believers" was considered desirable. Examples are the Crusades against the Cathars and the Baltic people in the thirteenth century.[4] Likewise the inhabitants of conquered cities were frequently massacred during the Crusades against the Turks in the eleventh and twelfth centuries, or during the Muslim and Ottoman Turkish incursions in Europe throughout the period. Thus, there was little concept of prisoner of war during this time.

Rulers and army commanders, however, were frequently used to extract tribute by granting their freedom in exchange for a significant ransom in treasury or land, necessitating their detainment until the transaction was complete.

Seventeenth to mid-twentieth centuries

In 1625 the Dutch philosopher Hugo Grotius wrote On the Law of War and Peace, which defined the criteria for just war as he saw it. In Grotius' just war, warring states would aim to do as little damage as possible, which is one result of just wars occurring only as a last resort. A part of causing as little damage possible was the treatment of enemy combatants. Grotius emphasized that combatants should be treated humanely.

The Treaty of Westphalia of 1648, which ended the Thirty Years War, is considered the first to establish the rule of releasing prisoners at the end of hostilities and allowing them to return to their homelands.[5]

French philosopher Montesquieu wrote The Spirit of Laws in 1748, in which he defined his own views on the rights of POWs. Montesquieu opposed slavery in general and afforded many rights to prisoners. In this work he argued that captors have no right to do any harm to their prisoners. The only thing captors should be allowed to do is disarm their prisoners to keep them from causing harm to others.[6]

During the nineteenth century, there were increased efforts to improve the treatment and processing of prisoners. The extensive period of conflict during the Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars (1793-1815), followed by the Anglo - American War of 1812, led to the emergence of a cartel system for the exchange of prisoners, even while the belligerents were at war. A cartel was usually arranged by the respective armed service for the exchange of like-ranked personnel. The aim was to achieve a reduction in the number of prisoners held, while at the same time alleviating shortages of skilled personnel in the home country.

Later, as result of these emerging conventions a number of international conferences were held, starting with the Brussels Conference of 1874, with nations agreeing that it was necessary to prevent inhumane treatment of prisoners and the use of weapons causing unnecessary harm. Although no agreements were ratified by the participating nations, work was continued that resulted in new conventions being adopted and becoming recognized as international law, which specified that prisoners of war are required to be treated humanely and diplomatically.

The first systematic treatment of prisoners of war came during the American Civil War during which the political philosopher Francis Lieber wrote Instructions for the Government of Armies of the United States in the Field for the Union army.[7] This work attempted to codify the laws of war, including those relating to the treatment of POWs. It is estimated that there were 400,000 prisoners of war, not counting all of those involved in the parole of prisoners practiced until the time prisons could be built. [8]

World War I

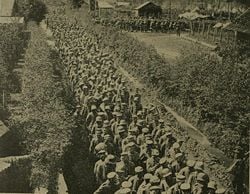

During World War I about eight million men surrendered and were held in POW camps until the war ended. All nations pledged to follow the Hague rules on fair treatment of prisoners of war, and in general the POWs had a much higher survival rate than their peers who were not captured.[9] Individual surrenders were uncommon; usually a large unit surrendered all its men. At Tannenberg 92,000 Russians surrendered during the battle. When the besieged garrison of Kaunas surrendered in 1915, 20,000 Russians became prisoners. Over half the Russian losses were prisoners (as a proportion of those captured, wounded, or killed); for Austria 32 percent, for Italy 26 percent, for France 12 percent, for Germany 9 percent, and for Britain 7 percent. Prisoners from the Allied armies totaled about 1.4 million (not including Russia, which lost between 2.5 and 3.5 million men as prisoners.) From the Central Powers about 3.3 million men became prisoners.[10]

Germany held 2.5 million prisoners; Russia held 2.9 million, and Britain and France held about 720,000, mostly gained in the period just before the Armistice in 1918. The US held 48,000. The most dangerous moment was the act of surrender, when helpless soldiers were sometimes gunned down. Once prisoners reached a camp in general conditions were satisfactory (and much better than in World War II), thanks in part to the efforts of the International Red Cross and inspections by neutral nations. Conditions were, however, terrible in Russia—starvation was common for prisoners and civilians alike; about 15-20 percent of the prisoners in Russia died. In Germany food was short but only 5 percent died.[11][12][13]

The Ottoman Empire often treated prisoners of war poorly. Some 11,800 British Empire soldiers, most of them Indians became prisoners after the five-month Siege of Kut, in Mesopotamia, in April 1916. Many were weak and starved when they surrendered and 4,250 died in captivity.[14]

By December 9, 264,000 prisoners had been repatriated. A very large number of these were released en masse and sent across allied lines without any food or shelter. This created difficulties for the receiving Allies and many died from exhaustion. The released POWs were met by cavalry troops and sent back through the lines to reception centers where they were refitted with boots and clothing and dispatched to the ports in trains. Upon arrival at the receiving camp the POWs were registered and “boarded” before being dispatched to their own homes. All officers had to write a report on the circumstances of their capture and to ensure that they had done all they could to avoid capture. On a more enlightened note, each returning officer and man was given a message from King George V, written in his own hand and reproduced on a lithograph. It read as follows:

The Queen joins me in welcoming you on your release from the miseries & hardships, which you have endured with so much patience and courage.

During these many months of trial, the early rescue of our gallant Officers & Men from the cruelties of their captivity has been uppermost in our thoughts.

We are thankful that this longed for day has arrived, & that back in the old Country you will be able once more to enjoy the happiness of a home & to see good days among those who anxiously look for your return.

George R.I.

Modern times

World War II

During World War II, Germany and Italy generally treated prisoners from the British Commonwealth, France, the U.S. and other western allies, in accordance with the Third Geneva Convention (1929) which had been signed by these countries.[15] Nazi Germany did not extend this level of treatment to non-Western prisoners, who suffered harsh captivities and died in large numbers while in captivity. The Soviet Union and the Empire of Japan also did not treat prisoners of war in accordance with the Geneva Convention.

When soldiers of lower rank were made to work, they were compensated, and officers (such as in Colditz Castle) were not forced to work. The main complaint of prisoners of war in German Army camps, especially during the last two years of the war, was the poor quality and miserly quantities of food provided, a fate German soldiers and civilians were also suffering due to the blockade conditions. Fortunately for the prisoners, food packages provided by the International Red Cross supplemented the food rations, until the last few months when allied air raids prevented shipments from arriving. The other main complaint was the harsh treatment during forced marches in the last months resulting from German attempts to keep prisoners away from the advancing allied forces.

In contrast Germany treated the Soviet Red Army troops that had been taken prisoner with neglect and deliberate, organized brutality. The Nazi Government regarded Soviet POWs as being of a lower racial order, in keeping with the Third Reich's policy of "racial purification." As a result Soviet POWs were held under conditions that resulted in deaths of hundreds of thousands from starvation and disease. Most prisoners were also subjected to forced labor under conditions that resulted in further deaths. An official justification used by the Germans for this policy was that the Soviet Union had not signed the Geneva Convention; this was not legally justifiable however as under article 82 of the Third Geneva Convention of 1929; signatory countries had to give POWs of all signatory and non-signatory countries the rights assigned by the convention.

On the Soviet side, the claimed justification for the harsh treatment of German Army prisoners, and those of the forces of other Axis powers, was that they had forfeited their right to fair treatment, because of the widespread crimes committed against Soviet civilians during the invasion of the Soviet Union. German POWs were used for forced labor under conditions that resulted in deaths of hundreds of thousands. One specific example of Soviet cruelty towards the German POWs was after the Battle of Stalingrad during which the Soviets had captured 91,000 German troops. The prisoners, already starved and ill, were marched to war camps in Siberia to face the bitter cold. Of the troops captured in Stalingrad, only 5,000 survived. The last German POWs were released only in 1955, after Stalin had died.

German soldiers, numbering approximately one million, who surrendered to American forces were placed in Rheinwiesenlager (Rhine meadow camps), officially named Prisoner of War Temporary Enclosures (PWTE). It was decided to treat these prisoners as "Disarmed Enemy Forces (DEF)" who could be denied the rights of prisoners of war guaranteed by the Geneva Convention. The Americans transferred the interior administration of the camps to German prisoners. Estimates for German POW deaths in these camps range from about 3,000 to 10,000, in most part occurring from starvation, dehydration, and exposure to the weather elements. Although Germany surrendered in May 1945 the Allied leadership was worried the Germans would conduct an effective guerrilla warfare against their occupation, and so Germans were held in these transit camps until late summer 1945. The decision to keep them in the poor conditions of Rheinwiesenlager camps for months (despite the war being over) was "mainly to prevent Werwolf activity".[16]

In the Pacific War, the Empire of Japan did neither sign nor follow the Third Geneva Convention of 1929. Prisoners of war from America, Australia, Britain, Canada, Netherlands, and New Zealand held by the Japanese armed forces were subject to brutal treatment, including forced labor, medical experimentation, starvation rations, and poor medical treatment. No access was provided to the International Red Cross. This treatment resulted in the very high death rate of 27 percent of Western prisoners in Japanese prisoner of war camps. Escapes were almost impossible because of the difficulty of men of European descent hiding in Asian societies.[17]

The total death rate for POWs in World War II are shown in the following table.[18]

Percentage of

POWs who diedItalian POWs held by Soviets 84.5% Russian POWs held by Germans 57.5% German POWs held by Soviets 35.8% American POWs held by Japanese 33.0% German POWs held by Eastern Europeans 32.9% British POWs held by Japanese 24.8% British POWs held by Germans 3.5% German POWs held by French 2.58% German POWs held by Americans 0.15% German POWs held by British 0.03%

Korean War

During the Korean War the Korean government promised to abide by the Geneva Convention regarding the treatment of prisoners, but did not completely comply. The government did not recognize the Red Cross as an impartial organization and refused it access to any prisoners of war. Some prisoners also refused to be repatriated following the end of the conflict, which established a new precedent for political asylum for POWs.

Vietnam War

The governments of both North and South Vietnam were guilty of violating the Geneva Convention regarding their treatment of POWs during the Vietnam War. North Vietnam did not fully report all of their prisoners, nor did they allow impartial access to the prisoners or for the prisoners to correspond with their own nations. The South Vietnamese were accused of torturing prisoners and leaving them in inhumane prisons. Many American servicemen were still missing following the war, and although the US Department of Defense's list of POWs/MIAs (missing in action) still contains people who are unaccounted for, the last official POW of the conflict was declared dead in 1994.[19]

War on Terror

America's war on terror during the early twenty-first century has resulted in great controversy of the definition of POWs. America is a signatory of the Geneva Convention and as such has certain responsibilities in detaining prisoners. The administration of George W. Bush decided that people taken prisoner in the multi-nation war on terrorism following the attacks of September 11, 2001 are not to be accorded the same rights as traditional prisoners of war due to the atypical method of war being fought. As a result, the US imprisoned some 700 men at a prison at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba and refused them access to lawyers and held them without charge. These prisoners were all termed "unlawful combatants." In 2004, the United States Supreme Court ruled that these prisoners had the right to challenge their detention.

Notes

- ↑ Care of Enemy Prisoners of War/Internees United States Army Institute of Surgical Research. Retrieved April 10, 2007.

- ↑ Chapter II: Prisoners of War Hague Convention of 1907, IV Convention Respecting the Laws and Customs of War on Land Retrieved October 15, 2007.

- ↑ Convention (III) relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War Geneva, 12 August 1949. www.icrc.org. Retrieved October 15, 2007.

- ↑ Norman Davies. History of Europe. (Oxford University Press, 1996), 362

- ↑ "Prisoner of war," Encyclopedia Brittanica.

- ↑ Charles de Montesquieu, "Origin of the Right of Slavery among the Roman Civilians," The Spirit of Laws, Book XV: In What Manner the Laws of Civil Slavery Relate to the Nature of the Climate.

- ↑ Francis Lieber, General Orders No. 100 : The Lieber Cod Avalon Project. Retrieved May 19, 2011.

- ↑ Patricia Faust (ed.), Historical Times Encyclopedia of the Civil War (New York, NY: HarperCollins Publishers, 1991).

- ↑ Geo G. Phillimore and Hugh H. L. Bellot, "Treatment of Prisoners of War" In Transactions of the Grotius Society, Vol. 5, (1919), 47-64.

- ↑ Niall Ferguson, The Pity of War: Explaining World War I. (New York: Basic Books, 1999), 368-369 for data.

- ↑ Richard B. Speed, Prisoners, Diplomats and the Great War: A Study in the Diplomacy of Captivity (Greenwood Press, 1990, ISBN 978-0313267291)

- ↑ Ferguson, The Pity of War (1999), ch 13.

- ↑ Desmond Morton, Silent Battle: Canadian Prisoners of War in Germany, 1914-1919. (Lester Publications, 1992).

- ↑ "The Mesopotamia campaign" British National Archives. Retrieved October 15, 2007.

- ↑ Convention relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War. Geneva, 27 July 1929 International Committee of the Red Cross. Retrieved April 10, 2007.

- ↑ Perry Biddiscombe, Werwolf!: The History of the National Socialist Guerrilla Movement, 1944-1946 (University of Toronto Press, 1998, ISBN 978-0802008626), 253.

- ↑ Gavin Daws, Prisoners of the Japanese: Pows of World War II in the Pacific. (New York, NY: Harper Perennial, 1996, ISBN 978-0688143701).

- ↑ Niall Ferguson, "Prisoner Taking and Prisoner Killing in the Age of Total War: Towards a Political Economy of Military Defeat," War in History 11(2) (2004): 148-192.

- ↑ "Children of the Last P.O.W. Close a Pain-Filled Chapter." The New York Times October 05, 1994. Retrieved May 19, 2011.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Biddiscombe, Perry. Werwolf!: The History of the National Socialist Guerrilla Movement, 1944-1946. University of Toronto Press, 1998. ISBN 978-0802008626

- Carlson, Lewis H. We Were Each Other's Prisoners: An oral history of World War II American and German Prisoners Of War. New York, NY: BasicBooks (HarperCollins, Inc.), 1997. ISBN 0465091202

- Davies, Norman. Europe: A History. Oxford University Press, 1996. ISBN 978-0195209129

- Daws, Gavin. Prisoners of the Japanese: Pows of World War II in the Pacific. New York, NY: Harper Perennial, 1996. ISBN 978-0688143701

- Faust, Patricia (ed.). Historical Times Encyclopedia of the Civil War New York, NY: HarperCollins Publishers, 1991. ISBN 0062715356

- Ferguson, Niall. The Pity of War: Explaining World War I. New York: Basic Books, 1999. ASIN B0012G5Y1Q

- Gascar, Pierre. Histoire de la captivité des Français en Allemagne (1939-1945). France: Éditions Gallimard, (in French), 1967.

- Krammer, Arnold. Nazi Prisoners of War in America. Scarborough House, 1996. ISBN 0812885619

- McGowran, Tom. Beyond the Bamboo Screen: Scottish Prisoners of War under the Japanese. Dunfermline, UK: Cualann Press Ltd, 2000. ISBN 978-0953503612

- Moore, Bob, and Kent Fedorowich. Prisoners of War and their Captors in World War II. Oxford, UK: Berg Press, 1996. ISBN 978-1859731529

- Morton, Desmond. Silent Battle: Canadian Prisoners of War in Germany, 1914-1919. Lester Publications, 1992. ISBN 1895555175

- Passfield, Alfred James. The Escape Artist. Artlook Books, 1988. ISBN 0864450478

- Phillimore, Geo G., and Hugh H. L. Bellot. "Treatment of Prisoners of War," Transactions of the Grotius Society 5 (1919).

- Rolf, David. Prisoners of the Reich, Germany’s Captives, 1939-45. Coronet Books, 1998. ISBN 978-0340508206

- Speed, Richard B. Prisoners, Diplomats, and the Great War: A Study in the Diplomacy of Captivity. Greenwood Press, 1990. ISBN 978-0313267291

- Wiggers, Richard D. "The United States and the Denial of Prisoner of War (POW) Status at the End of the Second World War," Militargeschichtliche Mitteilungen 52 (1993): 91-94.

- Winton, Andrew. Open Road to Faraway: Escapes from Nazi POW Camps 1941-1945. Dunfermline, UK: Cualann Press Ltd, 2001. ISBN 978-0953503650

External links

All links retrieved November 30, 2022.

- Prisoner of War 1942-1945 Frank Larkin.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.