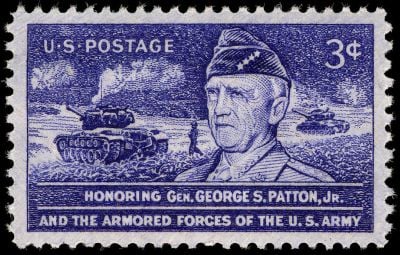

| George S. Patton | |

|---|---|

| November 11, 1885 – December 21, 1945 | |

Patton in 1945 | |

| Nickname | "Bandito" "Old Blood and Guts" |

| Place of birth | San Gabriel, California, U.S. |

| Place of death | Heidelberg, Allied-occupied Germany |

| Place of burial | Luxembourg American Cemetery and Memorial |

| Allegiance | United States of America |

| Service/branch | United States Army |

| Years of service | 1908–1945 |

| Rank | General |

| Unit | Cavalry Branch, Armor Branch |

| Commands held | Fifteenth United States Army Third United States Army Seventh United States Army II Corps Desert Training Center I Armored Corps 2nd Armored Division 2nd Brigade, 2nd Armored Division 3d Cavalry Regiment 5th Cavalry Regiment 3rd Squadron, 3rd Cavalry 304th Tank Brigade |

| Battles/wars | Mexican Revolution

|

| Awards | Distinguished Service Cross (2) Army Distinguished Service Medal (3) Silver Star (2) Legion of Merit Bronze Star Medal Purple Heart |

| Alma mater | United States Military Academy |

| Spouse | Beatrice Banning Ayer (m. 1910) |

| Children | Beatrice Smith Ruth Ellen George Patton IV |

| Relations | George Smith Patton II (father) George Smith Patton I (grandfather) Benjamin Davis Wilson (grandfather) John K. Waters (son-in-law) |

George Smith Patton Jr. (November 11, 1885 – December 21, 1945) was a general of the United States Army who commanded the U.S. Seventh Army in the Mediterranean theater of World War II, and the U.S. Third Army in France and Germany after the Allied invasion of Normandy in June 1944.

Born in 1885, Patton attended the Virginia Military Institute and the U.S. Military Academy at West Point. Patton first saw combat during 1916s Pancho Villa Expedition, America's first military action using motor vehicles. He saw action in World War I as part of the new United States Tank Corps of the American Expeditionary Forces. He commanded the U.S. tank school in France, then led tanks into combat and was wounded near the end of the war. In the interwar period, Patton became a central figure in the development of the Army's armored warfare doctrine, serving in numerous staff positions throughout the country. At the American entry into World War II, he commanded the 2nd Armored Division.

Patton led U.S. troops into the Mediterranean theater with an invasion of Casablanca during Operation Torch in 1942, and soon established himself as an effective commander by rapidly rehabilitating the demoralized U.S. II Corps. He commanded the U.S. Seventh Army during the Allied invasion of Sicily, where he was the first Allied commander to reach Messina. There he was embroiled in controversy after he slapped two shell-shocked soldiers, and was temporarily removed from battlefield command. He then was assigned a key role in Operation Fortitude, the Allies' disinformation campaign for Operation Overlord. At the start of the Western Allied invasion of France, Patton was given command of the Third Army, which conducted a highly successful rapid armored drive across France. Under his decisive leadership, the Third Army took the lead in relieving beleaguered American troops at Bastogne during the Battle of the Bulge, after which his forces drove deep into Nazi Germany by the end of the war.

During the Allied occupation of Germany, Patton was severely injured in an auto accident. He died in Germany twelve days later, on December 21, 1945. Patton's colorful image, hard-driving personality and success as a commander were at times overshadowed by his controversial public statements. His emphasis on rapid and aggressive offensive action proved effective, and he was regarded highly by his opponents in the German High Command. An award-winning biographical film released in 1970, Patton, helped solidify his image as an American folk hero.

Early life

George Smith Patton Jr. was born on November 11, 1885,[1] in San Gabriel, California, to George Smith Patton Sr. and his wife Ruth Wilson, the daughter of Benjamin Davis Wilson. Patton had a younger sister, Anne, who was nicknamed "Nita."[2]

As a child, Patton had difficulty learning to read and write, but eventually overcame this and was known in his adult life to be an avid reader.Historians Carlo D'Este and Alan Axelrod note in their biographies of Patton that these difficulties were likely the result of undiagnosed dyslexia. He was tutored from home until the age of eleven, when he was enrolled in Stephen Clark's School for Boys, a private school in Pasadena, for six years. Patton was described as an intelligent boy and was widely read on classical military history, particularly the exploits of Hannibal, Scipio Africanus, Julius Caesar, Joan of Arc, and Napoleon Bonaparte, as well as those of family friend John Singleton Mosby, who frequently stopped by the Patton family home when George was a child.[3] He was also a devoted horseback rider.[4]

Patton married Beatrice Banning Ayer, the daughter of Boston industrialist Frederick Ayer, on May 26, 1910, in Beverly Farms, Massachusetts. They had three children, Beatrice Smith (born March 1911), Ruth Ellen (born February 1915), and George Patton IV (born December 1923).[5] Beatrice Patton died in 1954 when she was thrown from her horse.[6]

Patton never seriously considered a career other than the military.[7] At the age of seventeen he sought an appointment to the United States Military Academy at West Point, New York. He applied to several universities with Reserve Officer's Training Corps programs, and was accepted to Princeton College, but eventually decided on Virginia Military Institute (VMI), which his father and grandfather had attended.[8] He attended the school from 1903 to 1904 and, though he struggled with reading and writing, performed exceptionally in uniform and appearance inspection as well as military drill. While he was at VMI, a senator from California nominated him for West Point.[9] He was an initiate of the Beta Commission of Kappa Alpha Order.[10]

In his plebe (first) year at West Point, Patton adjusted easily to the routine. However, his academic performance was so poor that he was forced to repeat his first year after failing mathematics.[11] He excelled at military drills though his academic performance remained average. He was cadet sergeant major during his junior year, and the cadet adjutant his senior year. He also joined the football team, but he injured his arm and stopped playing on several occasions. Instead he tried out for the sword team and track and field and specialized in the modern pentathlon.[12] He competed in this sport in the 1912 Summer Olympics in Stockholm, and he finished in fifth place—right behind four Swedes.[13]

Patton graduated number 46 out of 103 cadets at West Point on June 11, 1908, and received a commission as a second lieutenant in the Cavalry branch of the United States Army.[14]

Ancestry

The Patton family was of Irish, Scots-Irish, English, Scottish, French and Welsh ancestry. His great-grandmother came from an aristocratic Welsh family, descended from many Welsh lords of Glamorgan,[15] which had an extensive military background. Patton believed he had former lives as a soldier and took pride in mystical ties with his ancestors.[16][17] Though not directly descended from George Washington, Patton traced some of his English colonial roots to George Washington's great-grandfather. He was also descended from England's King Edward I through Edward's son Edmund of Woodstock, 1st Earl of Kent. Family belief held the Pattons were descended from sixteen barons who had signed the Magna Carta.[18] Patton believed in reincarnation, stating that he had fought in previous battles and wars before his time, additionally, his ancestry was very important to him, forming a central part of his personal identity.[19] The first Patton in America was Robert Patton, born in Ayr, Scotland. He emigrated to Culpeper, Virginia, from Glasgow, in either 1769 or 1770.[20] His paternal grandfather was George Smith Patton, who commanded the 22nd Virginia Infantry under Jubal Early in the Civil War and was killed in the Third Battle of Winchester, while his great-uncle Waller T. Patton was killed in Pickett's Charge during the Battle of Gettysburg. Patton also descended from Hugh Mercer, who had been killed in the Battle of Princeton during the American Revolution. Patton's father, who graduated from the Virginia Military Institute (VMI), became a lawyer and later the district attorney of Los Angeles County. Patton's maternal grandfather was Benjamin Davis Wilson, a merchant who had been the second Mayor of Los Angeles. His father was a wealthy rancher and lawyer who owned a 1,000-acre (400 ha) ranch near Pasadena, California.[21] Patton is also a descendant of French Huguenot Louis DuBois.[22]

Junior officer

Patton's first posting was with the 15th Cavalry at Fort Sheridan, Illinois,[23] where he established himself as a hard-driving leader who impressed superiors with his dedication.[24] In late 1911, Patton was transferred to Fort Myer, Virginia, where many of the Army's senior leaders were stationed. Befriending Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson, Patton served as his aide at social functions in addition to his regular duties as quartermaster for his troop.[25]

1912 Olympics

For his skill in running and fencing, Patton was selected as the Army's entry for the first modern pentathlon at the 1912 Olympic Games in Stockholm, Sweden.[26] Of 42 competitors, Patton placed twenty-first on the pistol range, seventh in swimming, fourth in fencing, sixth in the equestrian competition, and third in the footrace, finishing fifth overall and first among the non-Swedish competitors.[27] There was some controversy concerning his performance in the pistol shooting competition, where he used a .38 caliber pistol while most of the other competitors chose .22 caliber firearms. He claimed that the holes in the paper from his early shots were so large that some of his later bullets passed through them, but the judges decided he missed the target completely once. Modern competitions on this level frequently now employ a moving backdrop to specifically track multiple shots through the same hole. If his assertion was correct, Patton would likely have won an Olympic medal in the event.[28] The judges' ruling was upheld. Patton's only comment on the matter was:

The high spirit of sportsmanship and generosity manifested throughout speaks volumes for the character of the officers of the present day. There was not a single incident of a protest or any unsportsman-like quibbling or fighting for points which I may say, marred some of the other civilian competitions at the Olympic Games. Each man did his best and took what fortune sent them like a true soldier, and at the end we all felt more like good friends and comrades than rivals in a severe competition, yet this spirit of friendship in no manner detracted from the zeal with which all strove for success.[29]

Sword design

Following the 1912 Olympics, Patton traveled to Saumur, France, where he learned fencing techniques from Adjutant Charles Cléry, a French "master of arms" and instructor of fencing at the cavalry school there.[30] Bringing these lessons back to Fort Myer, Patton redesigned saber combat doctrine for the U.S. cavalry, favoring thrusting attacks over the standard slashing maneuver and designing a new sword for such attacks. He was temporarily assigned to the Office of the Army Chief of Staff, and in 1913, the first 20,000 of the Model 1913 Cavalry Saber—popularly known as the "Patton saber"—were ordered. Patton then returned to Saumur to learn advanced techniques before bringing his skills to the Mounted Service School at Fort Riley, Kansas, where he would be both a student and a fencing instructor. He was the first Army officer to be designated "Master of the Sword,"[31] a title denoting the school's top instructor in swordsmanship.[32] Arriving in September 1913, he taught fencing to other cavalry officers, many of whom were senior to him in rank.[33] Patton graduated from this school in June 1915. He was originally assigned to return to the 15th Cavalry,[34] which was bound for the Philippines. Fearing this assignment would dead-end his career, Patton traveled to Washington, D.C. during 11 days of leave and convinced influential friends to arrange a reassignment for him to the 8th Cavalry at Fort Bliss, Texas, anticipating that instability in Mexico might boil over into a full-scale civil war.[35] In the meantime, Patton was selected to participate in the 1916 Summer Olympics, but that Olympiad was cancelled due to World War I.[36]

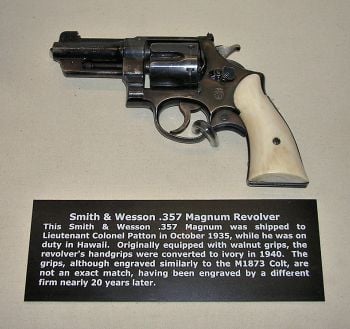

Pancho Villa Expedition

In 1915 Patton was assigned to border patrol duty with A Troop of the 8th Cavalry, based in Sierra Blanca.[37] During his time in the town, Patton took to wearing his M1911 Colt .45 in his belt rather than a holster. His firearm discharged accidentally one night in a saloon, so he swapped it for an ivory-handled Colt Single Action Army revolver, a weapon that would later become an icon of Patton's image.[38]

In March 1916 Mexican forces loyal to Pancho Villa crossed into New Mexico and raided the border town of Columbus. The violence in Columbus killed several Americans. In response, the U.S. launched the Pancho Villa Expedition into Mexico. Chagrined to discover that his unit would not participate, Patton appealed to expedition commander John J. Pershing, and was named his personal aide for the expedition. This meant that Patton would have some role in organizing the effort, and his eagerness and dedication to the task impressed Pershing.[39] Patton modeled much of his leadership style after Pershing, who favored strong, decisive actions and commanding from the front.[40][41] As an aide, Patton oversaw the logistics of Pershing's transportation and acted as his personal courier.[42]

In mid-April, Patton asked Pershing for the opportunity to command troops, and was assigned to Troop C of the 13th Cavalry to assist in the manhunt for Villa and his subordinates.[44] His initial combat experience came on May 14, 1916 in what would become the first motorized attack in the history of U.S. warfare. A force under his command of ten soldiers and two civilian guides with the 6th Infantry in three Dodge touring cars surprised three of Villa's men during a foraging expedition, killing Julio Cárdenas and two of his guards.[45] It was not clear if Patton personally killed any of the men, but he was known to have wounded all three.[46] The incident garnered Patton both Pershing's good favor and widespread media attention as a "bandit killer."[47] Shortly after, he was promoted to first lieutenant while a part of the 10th Cavalry on May 23, 1916.[48] Patton remained in Mexico until the end of the year. President Woodrow Wilson forbade the expedition from conducting aggressive patrols deeper into Mexico, so it remained encamped in the Mexican border states for much of that time. In October Patton briefly withdrew to California after being burned by an exploding gas lamp.[49] He returned from the expedition permanently in February 1917.[50]

World War I

After the Villa Expedition, Patton was detailed to Front Royal, Virginia, to oversee horse procurement for the Army, but Pershing intervened on his behalf. After the United States entered World War I, and Pershing was named commander of the American Expeditionary Force (AEF) on the Western Front, Patton requested to join his staff.[51] Patton was promoted to captain on May 15, 1917 and left for Europe among the 180 men of Pershing's advance party, which departed May 28 and arrived in Liverpool, England on June 8. Taken as Pershing's personal aide, Patton oversaw the training of American troops in Paris until September, then moved to Chaumont and was assigned as a post adjutant, commanding the headquarters company overseeing the base. Patton was dissatisfied with the post and began to take an interest in tanks, as Pershing sought to give him command of an infantry battalion.[52] While in a hospital for jaundice, Patton met Colonel Fox Conner, who encouraged him to work with tanks instead of infantry.[53]

On November 10, 1917 Patton was assigned to establish the AEF Light Tank School.[54] He left Paris and reported to the French Army's tank training school at Champlieu near Orrouy, where he drove a Renault FT light tank. On November 20, the British launched an offensive towards the important rail center of Cambrai, using an unprecedented number of tanks.[55] At the conclusion of his tour on December 1, Patton went to Albert, 30 miles (48 km) from Cambrai, to be briefed on the results of this attack by the chief of staff of the British Tank Corps, Colonel J. F. C. Fuller.[56] On the way back to Paris, he visited the Renault factory to observe the tanks being manufactured. Patton was promoted to major on January 26, 1918.[57] He received the first ten tanks on March 23, 1918 at the tank school at Bourg, a small village close to Langres, Haute-Marne département. The only US soldier with tank-driving experience, Patton personally backed seven of the tanks off the train.[58] In the post, Patton trained tank crews to operate in support of infantry, and promoted its acceptance among reluctant infantry officers.[59] He was promoted to lieutenant colonel on April 3, 1918, and attended the Command and General Staff College in Langres.[60]

In August 1918, he was placed in charge of the U.S. 1st Provisional Tank Brigade (redesignated the 304th Tank Brigade on November 6, 1918). Patton's Light Tank Brigade was part of Colonel Samuel Rockenbach's Tank Corps, part of the American First Army.[61] Personally overseeing the logistics of the tanks in their first combat use by U.S. forces, and reconnoitering the target area for their first attack himself, Patton ordered that no U.S. tank be surrendered.[62] Patton commanded American-crewed Renault FT tanks at the Battle of Saint-Mihiel,[63] leading the tanks from the front for much of their attack, which began on September 12. He walked in front of the tanks into the German-held village of Essey, and rode on top of a tank during the attack into Pannes, seeking to inspire his men.[64]

Patton's brigade was then moved to support U.S. I Corps in the Meuse-Argonne Offensive on September 26.[65] He personally led a troop of tanks through thick fog as they advanced 5 miles (8 km) into German lines. Around 09:00, Patton was wounded while leading six men and a tank in an attack on German machine guns near the town of Cheppy.[66] His orderly, Private First Class Joe Angelo, saved Patton, dragging him to safety under enemy fire. Angelo was later awarded the Distinguished Service Cross for his bravery.[67] Patton commanded the battle from a shell hole for another hour before being evacuated. Although the 35th Division (of which Patton's tank troop was a component) eventually captured Varennes, it did so with heavy losses.[68] Trying to move his reserve tanks forward and losing control of his temper, Patton is quoted as potentially having murdered one of his own men, stating: "Some of my reserve tanks were stuck by some trenches. So I went back and made some Americans hiding in the trenches dig a passage. I think I killed one man here. He would not work so I hit him over the head with a shovel".[69]

Patton stopped at a rear command post to submit his report before heading to a hospital. Sereno E. Brett, commander of the U.S. 326th Tank Battalion, took command of the brigade in Patton's absence. Patton wrote in a letter to his wife: "The bullet went into the front of my left leg and came out just at the crack of my bottom about two inches to the left of my rectum. It was fired at about 50 m so made a hole about the size of a [silver] dollar where it came out."[70]

While recuperating from his wound, Patton was brevetted to colonel in the Tank Corps of the U.S. National Army on October 17. He returned to duty on October 28 but saw no further action before hostilities ended on his 33rd birthday with the armistice of November 11, 1918.[71] For his actions in Cheppy, Patton received the Distinguished Service Cross. For his leadership of the brigade and tank school, he was awarded the Distinguished Service Medal. He was also awarded the Purple Heart for his combat wounds after the decoration was created in 1932.[72]

Inter-war years

Patton left France for New York City on March 2, 1919. After the war, he was assigned to Camp Meade, Maryland, and reverted to his permanent rank of captain on June 30, 1920, though he was promoted to major again the next day. Patton was given temporary duty in Washington D.C. to serve on a committee writing a manual on tank operations. During this time he developed a belief that tanks should be used not as infantry support, but rather as an independent fighting force. Patton supported the M1919 tank design created by J. Walter Christie, a project which was shelved due to financial concerns.[73] While on duty in Washington, D.C., in 1919, Patton met Dwight D. Eisenhower,[74] who would play an enormous role in Patton's future career. During and following Patton's assignment in Hawaii, he and Eisenhower corresponded frequently. Patton sent Eisenhower notes and assistance to help him graduate from the General Staff College.[75] With Christie, Eisenhower, and a handful of other officers, Patton pushed for more development of armored warfare in the interwar era. These thoughts resonated with Secretary of War Dwight Davis, but the limited military budget and prevalence of already-established Infantry and Cavalry branches meant the U.S. would not develop its armored corps much until 1940.[76]

On September 30, 1920, then-Major Patton relinquished command of the 304th Tank Brigade and was reassigned to Fort Myer as commander of 3rd Squadron, 3rd Cavalry. Loathing duty as a peacetime staff officer, he spent much time writing technical papers and giving speeches on his combat experiences at the General Staff College.[77]

In July 1921 Patton became a member of the American Legion Tank Corps Post No. 19.[78] From 1922 to mid-1923 he attended the Field Officer's Course at the Cavalry School at Fort Riley, then he attended the Command and General Staff College from mid-1923 to mid-1924, graduating 25th out of 248.[79] In August 1923, Patton saved several children from drowning when they fell off a yacht during a boating trip off Salem, Massachusetts. He was awarded the Silver Lifesaving Medal for this action.[80] He was temporarily appointed to the General Staff Corps in Boston, Massachusetts, before being reassigned as G-1 and G-2 of the Hawaiian Division at Schofield Barracks in Honolulu in March 1925.[81]

Patton was made G-3 of the Hawaiian Division for several months, before being transferred in May 1927 to the Office of the Chief of Cavalry in Washington, D.C., where he began to develop the concepts of mechanized warfare. A short-lived experiment to merge infantry, cavalry and artillery into a combined arms force was cancelled after U.S. Congress removed funding. Patton left this office in 1931, returned to Massachusetts and attended the Army War College, becoming a "Distinguished Graduate" in June 1932.[82]

In July 1932, Patton was executive officer of the 3rd Cavalry, which was ordered to Washington by Army Chief of Staff General Douglas MacArthur. Patton took command of the 600 troops of the 3rd Cavalry, and on July 28, MacArthur ordered Patton's troops to advance on protesting veterans known as the "Bonus Army" with tear gas and bayonets. Patton was dissatisfied with MacArthur's conduct, as he recognized the legitimacy of the veterans' complaints and had himself earlier refused to issue the order to employ armed force to disperse the veterans. Patton later stated that, though he found the duty "most distasteful," he also felt that putting the marchers down prevented an insurrection and saved lives and property. He personally led the 3rd Cavalry down Pennsylvania Avenue, dispersing the protesters.[83] Patton also encountered his former orderly as one of the marchers and forcibly ordered him away, fearing such a meeting might make the headlines.[84]

Patton was promoted to lieutenant colonel in the regular Army on March 1, 1934, and was transferred to the Hawaiian Division in early 1935 to serve as G-2. Patton followed the growing hostility and conquest aspirations of the militant Japanese leadership. He wrote a plan to intern the Japanese living in the islands in the event of an attack as a result of the atrocities carried out by Japanese soldiers on the Chinese in the Sino-Japanese war. In 1937 he wrote a paper with the title "Surprise" which predicted, with what historian Carlo D'Este termed "chilling accuracy," a surprise attack by the Japanese on Hawaii.[85] Depressed at the lack of prospects for new conflict, Patton took to drinking heavily and allegedly began a brief affair with his 21-year-old niece by marriage, Jean Gordon. This supposed affair distressed his wife and nearly resulted in their separation. Patton's attempts to win her back were said to be among the few instances in which he willingly showed remorse or submission.[86]

Patton continued playing polo and sailing in this time. After sailing back to Los Angeles for extended leave in 1937, he was kicked by a horse and fractured his leg. Patton developed phlebitis from the injury, which nearly killed him. The incident almost forced Patton out of active service, but a six-month administrative assignment in the Academic Department at the Cavalry School at Fort Riley helped him to recover.[87] Patton was promoted to colonel on July 24, 1938 and given command of the 5th Cavalry at Fort Clark, Texas, for six months, a post he relished, but he was reassigned to Fort Myer again in December as commander of the 3rd Cavalry. There, he met Army Chief of Staff George C. Marshall, who was so impressed with him that Marshall considered Patton a prime candidate for promotion to general. In peacetime, though, he would remain a colonel to remain eligible to command a regiment.[88]

Patton had a personal schooner named When and If. The schooner was designed by famous naval architect John G. Alden and built in 1939. The schooner's name comes from Patton saying he would sail it "when and if" he returned from war.[89]

World War II

Following the German Army's invasion of Poland and the outbreak of World War II in Europe in September 1939, the U.S. military entered a period of mobilization, and Patton sought to build up the power of U.S. armored forces. During maneuvers the Third Army conducted in 1940, Patton met with Adna R. Chaffee Jr. and the two formulated recommendations to develop an armored force. Chaffee was named commander of this force, and created the 1st and 2nd Armored Divisions as well as the first combined arms doctrine. He named Patton commander of the 2nd Armored Brigade, part of the 2nd Armored Division. The division was one of few organized as a heavy formation with many tanks, and Patton was in charge of its training.[90] Patton was promoted to brigadier general on October 2, made acting division commander in November, and on April 4, 1941 was promoted again to major general and made Commanding General (CG) of the 2nd Armored Division.[91] As Chaffee stepped down from command of the I Armored Corps, Patton became the most prominent figure in U.S. armor doctrine. In December 1940, he staged a high-profile mass exercise in which 1,000 tanks and vehicles were driven from Columbus, Georgia, to Panama City, Florida, and back. He repeated the exercise with his entire division of 1,300 vehicles the next month.[92] Patton earned a pilot's license and, during these maneuvers, observed the movements of his vehicles from the air to find ways to deploy them effectively in combat.[93] His exploits earned him a spot on the cover of Life magazine.[94]

Patton led the division during the Tennessee Maneuvers in June 1941, and was lauded for his leadership, executing 48 hours' worth of planned objectives in only nine. During the September Louisiana Maneuvers, his division was part of the losing Red Army in Phase I, but in Phase II was assigned to the Blue Army. His division executed a 400-mile (640 km) end run around the Red Army and "captured" Shreveport, Louisiana. During the October–November Carolina Maneuvers, Patton's division captured Hugh Drum, commander of the opposing army.[95] On January 15, 1942 he was given command of I Armored Corps, and the next month established the Desert Training Center[96] in the Coachella Valley region of Riverside County in California, to run training exercises. He commenced these exercises in late 1941 and continued them into the summer of 1942. Patton chose a 10,000-acre (40 km²) expanse of desert area about 50 miles (80 km) southeast of Palm Springs.[97] From his first days as a commander, Patton strongly emphasized the need for armored forces to stay in constant contact with opposing forces. His instinctive preference for offensive movement was typified by an answer Patton gave to war correspondents in a 1944 press conference. In response to a question on whether the Third Army's rapid offensive across France should be slowed to reduce the number of U.S. casualties, Patton replied, "Whenever you slow anything down, you waste human lives."[98] It was around this time that a reporter, after hearing a speech where Patton said that it took "blood and brains" to win in combat, began calling him "blood and guts". The nickname would follow him for the rest of his life.[99] Soldiers under his command were known at times to have quipped, "our blood, his guts." Nonetheless, he was known to be admired widely by the men under his charge.[100]

North African Campaign

Under Lieutenant General Dwight D. Eisenhower, the Supreme Allied Commander, Patton was assigned to help plan the Allied invasion of French North Africa as part of Operation Torch in the summer of 1942.[101] Patton commanded the Western Task Force, consisting of 33,000 men in 100 ships, in landings centered on Casablanca, Morocco. The landings, which took place on November 8, 1942, were opposed by Vichy French forces, but Patton's men quickly gained a beachhead and pushed through fierce resistance. Casablanca fell on November 11 and Patton negotiated an armistice with French General Charles Noguès.[102] The Sultan of Morocco was so impressed that he presented Patton with the Order of Ouissam Alaouite, with the citation "Les Lions dans leurs tanières tremblent en le voyant approcher" (The lions in their dens tremble at his approach).[103] Patton oversaw the conversion of Casablanca into a military port and hosted the Casablanca Conference in January 1943.[104]

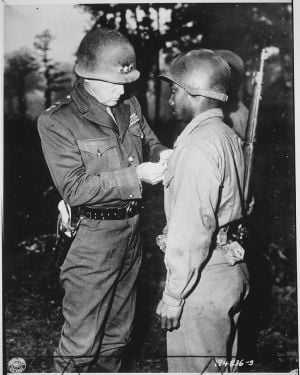

On March 6, 1943, following the defeat of the U.S. II Corps by the German Afrika Korps, commanded by Generalfeldmarschall Erwin Rommel, at the Battle of Kasserine Pass, Patton replaced Major General Lloyd Fredendall as Commanding General of the II Corps and was promoted to lieutenant general. Soon thereafter, he had Major General Omar Bradley reassigned to his corps as its deputy commander.[105] With orders to take the battered and demoralized formation into action in 10 days' time, Patton immediately introduced sweeping changes, ordering all soldiers to wear clean, pressed and complete uniforms, establishing rigorous schedules, and requiring strict adherence to military protocol. He continuously moved throughout the command talking with men, seeking to shape them into effective soldiers. He pushed them hard, and sought to reward them well for their accomplishments. His uncompromising leadership style is evidenced by his orders for an attack on a hill position near Gafsa, saying "I expect to see such casualties among officers, particularly staff officers, as will convince me that a serious effort has been made to capture this objective."[106]

Patton's training was effective, and on March 17, the U.S. 1st Infantry Division took Gafsa, winning the Battle of El Guettar, and pushing a German and Italian armored force back twice. In the meantime, on April 5, he removed Major General Orlando Ward, commanding the 1st Armored Division, after its lackluster performance at Maknassy against numerically inferior German forces. Advancing on Gabès, Patton's corps pressured the Mareth Line.[107] During this time, he reported to British General Sir Harold Alexander, commander of the 18th Army Group, and came into conflict with Air Vice Marshal Sir Arthur Coningham about the lack of close air support provided for his troops. When Coningham dispatched three officers to Patton's headquarters to persuade him that the British were providing ample air support, they came under German air attack mid-meeting, and part of the ceiling of Patton's office collapsed around them. Speaking later of the German pilots who had struck, Patton remarked, "if I could find the sons of bitches who flew those planes, I'd mail each of them a medal."[108] By the time his force reached Gabès, the Germans had abandoned it. He then relinquished command of II Corps to Bradley, and returned to the I Armored Corps in Casablanca to help plan Operation Husky, the Allied invasion of Sicily. Fearing U.S. troops would be sidelined, he convinced British commanders to allow them to continue fighting through to the end of the Tunisia Campaign before leaving on this new assignment.[109]

Sicily Campaign

For Operation Husky, the invasion of Sicily, Patton was to command the Seventh United States Army, dubbed the Western Task Force, in landings at Gela, Scoglitti and Licata to support landings by Bernard Montgomery's British Eighth Army. Patton's I Armored Corps was officially redesignated the Seventh Army just before his force of 90,000 landed before dawn on D-Day, July 10, 1943, on beaches near the town of Licata. The armada was hampered by wind and weather, but despite this the three U.S. infantry divisions involved, the 3rd, 1st, and 45th, secured their respective beaches. They repulsed counterattacks at Gela,[110] where Patton personally led his troops against German reinforcements from the Hermann Göring Division.[111]

Initially ordered to protect the British forces' left flank, Patton was granted permission by Alexander to take Palermo after Montgomery's forces became bogged down on the road to Messina. As part of a provisional corps under Major General Geoffrey Keyes, the 3rd Infantry Division under Major General Lucian Truscott covered 100 miles (160 km) in 72 hours, arriving at Palermo on July 21. Patton then set his sights on Messina.[112] He sought an amphibious assault, but it was delayed by lack of landing craft, and his troops did not land at Santo Stefano until August 8, by which time the Germans and Italians had already evacuated the bulk of their troops to mainland Italy. He ordered more landings on August 10 by the 3rd Infantry Division, which took heavy casualties but pushed the German forces back, and hastened the advance on Messina.[113] A third landing was completed on August 16, and by 22:00 that day Messina fell to his forces. By the end of the battle, the 200,000-man Seventh Army had suffered 7,500 casualties, and killed or captured 113,000 Axis troops and destroyed 3,500 vehicles. Still, 40,000 German and 70,000 Italian troops escaped to Italy with 10,000 vehicles.[114]

Patton's conduct in this campaign met with several controversies. He was also frequently in disagreement with Terry de la Mesa Allen Sr. and Theodore Roosevelt Jr. though, to their relief, he relented and supported Bradley's view.[115]

When Alexander sent a transmission on July 19 limiting Patton's attack on Messina, his chief of staff, Brigadier General Hobart R. Gay, claimed the message was "lost in transmission" until Messina had fallen.

In an incident on July 22, while a U.S. armored column was under attack from German aircraft, he shot and killed a pair of mules that had stopped while pulling a cart across a bridge. The cart was blocking the way of the column. When their Sicilian owner protested, Patton attacked him with a walking stick and had his troops push the two mule carcasses off the bridge.[116]

When informed of the Biscari massacre of prisoners, which was by troops under his command, Patton wrote in his diary, "I told Bradley that it was probably an exaggeration, but in any case to tell the officer to certify that the dead men were snipers or had attempted to escape or something, as it would make a stink in the press and also would make the civilians mad. Anyhow, they are dead, so nothing can be done about it."[117] Bradley refused Patton's suggestions. Patton later changed his mind. After he learned that the 45th Division's Inspector General found "no provocation on the part of the prisoners ... They had been slaughtered" Patton is reported to have said: "Try the bastards."[118]

Slapping incidents and aftermath

Two high-profile incidents of Patton striking subordinates during the Sicily campaign attracted national controversy following the end of the campaign. On August 3, 1943, Patton slapped and verbally abused Private Charles H. Kuhl at an evacuation hospital in Nicosia after he had been found to suffer from "battle fatigue".[119] On August 10, Patton slapped Private Paul G. Bennett under similar circumstances. Ordering both soldiers back to the front lines, Patton railed against cowardice and issued orders to his commanders to discipline any soldier making similar complaints.[120]

Word of the incident reached Eisenhower, who privately reprimanded Patton and insisted he apologize. Patton apologized to both soldiers individually, as well as to doctors who witnessed the incidents, and later to all of the soldiers under his command in several speeches.{[121] Eisenhower suppressed the incident in the media,[122] but in November journalist Drew Pearson revealed it on his radio program.[123] Criticism of Patton in the United States was harsh, and included members of Congress and former generals, Pershing among them.[124] The views of the general public remained mixed on the matter,[125] and eventually Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson stated that Patton must be retained as a commander because of the need for his "aggressive, winning leadership in the bitter battles which are to come before final victory."[126]

Patton did not command a force in combat for 11 months.[127] In September, Bradley, who was Patton's junior in both rank and experience, was selected to command the First United States Army forming in England to prepare for Operation Overlord.[128] This decision had been made before the slapping incidents were made public, but Patton blamed them for his being denied the command.[129] Eisenhower felt the invasion of Europe was too important to risk any uncertainty, and that the slapping incidents had been an example of Patton's inability to exercise discipline and self-control. While Eisenhower and Marshall both considered Patton to be a skilled combat commander, they felt Bradley was less impulsive and less prone to making mistakes.[130] On January 26, 1944, Patton was formally given command of the U.S. Third Army in England, a newly formed field Army, and he was assigned to prepare its inexperienced soldiers for combat in Europe.[131] This duty kept Patton busy during the first half of 1944.

Phantom Army

The German High Command had more respect for Patton than for any other Allied commander and considered him to be central to any plan to invade Europe from England.[132] Because of this, Patton was made a prominent figure in the deception operation, Fortitude, during the first half of 1944.[133] Through the British network of double-agents, the Allies fed German intelligence a steady stream of false reports about troops sightings and that Patton had been named commander of the First United States Army Group (FUSAG), all designed to convince the Germans that Patton was preparing this massive command for an invasion at Pas de Calais. FUSAG was in reality an intricately constructed fictitious army of decoys, props, and fake radio signal traffic based around Dover to mislead German reconnaissance planes and to make Axis leaders believe that a large force was massing there. This helped to mask the real location of the invasion in Normandy. Patton was ordered to keep a low profile to deceive the Germans into thinking that he was in Dover throughout early 1944, when he was actually training the Third Army. As a result of Operation Fortitude, the German 15th Army remained at the Pas de Calais to defend against Patton's supposed attack.[134] So strong was their conviction that this was the main landing area that the German army held its position there even after the invasion of Normandy on June 6, 1944. Patton flew to France a month later, and then returned to combat command.[135]

Normandy breakout offensive

Sailing to Normandy throughout July, Patton's Third Army formed on the extreme right (west) of the Allied land forces. Patton's friend Gilbert R. Cook was his deputy commander, whom Patton later had to relieve due to illness, a decision which "shook him to the core."[136] It became operational at noon on August 1, 1944, under Bradley's Twelfth United States Army Group. The Third Army simultaneously attacked west into Brittany, south, east toward the Seine, and north, assisting in trapping several hundred thousand German soldiers in the Falaise Pocket between Falaise and Argentan.[137]

Patton's strategy with his army favored speed and aggressive offensive action, though his forces saw less opposition than did the other three Allied field armies in the initial weeks of its advance.[138] The Third Army typically employed forward scout units to determine enemy strength and positions. Self-propelled artillery moved with the spearhead units and was sited well forward, ready to engage protected German positions with indirect fire. Light aircraft such as the Piper L-4 Cub served as artillery spotters and provided airborne reconnaissance. Once located, the armored infantry would attack using tanks as infantry support. Other armored units would then break through enemy lines and exploit any subsequent breach, constantly pressuring withdrawing German forces to prevent them from regrouping and reforming a cohesive defensive line. The U.S. armor advanced using reconnaissance by fire, and the .50 caliber M2 Browning heavy machine gun proved effective in this role, often flushing out and killing German panzerfaust teams waiting in ambush as well as breaking up German infantry assaults against the armored infantry.[139]

The speed of the advance forced Patton's units to rely heavily on air reconnaissance and tactical air support. The Third Army had by far more military intelligence (G-2) officers at headquarters specifically designated to coordinate air strikes than any other army.[140] Its attached close air support group was XIX Tactical Air Command, commanded by Brigadier General Otto P. Weyland. Developed originally by General Elwood Quesada of IX Tactical Air Command for the First Army in Operation Cobra, the technique of "armored column cover," in which close air support was directed by an air traffic controller in one of the attacking tanks, was used extensively by the Third Army. Each column was protected by a standing patrol of three to four P-47 and P-51 fighter-bombers as a combat air patrol (CAP).[141]

In its advance from Avranches to Argentan, the Third Army traversed 60 miles (97 km) in just two weeks. Patton's force was supplemented by Ultra intelligence for which he was briefed daily by his G-2, Colonel Oscar Koch, who apprised him of German counterattacks, and where to concentrate his forces.[142] Equally important to the advance of Third Army columns in northern France was the rapid advance of the supply echelons. Third Army logistics were overseen by Colonel Walter J. Muller, Patton's G-4, who emphasized flexibility, improvisation, and adaptation for Third Army supply echelons so forward units could rapidly exploit a breakthrough. Patton's rapid drive to Lorraine demonstrated his keen appreciation for the technological advantages of the U.S. Army. The major U.S. and Allied advantages were in mobility and air superiority. The U.S. Army had more trucks, more reliable tanks, and better radio communications, all of which contributed to a superior ability to operate at a rapid offensive pace.[143]

Lorraine Campaign

Patton's offensive came to a halt on August 31, 1944, as the Third Army ran out of fuel near the Moselle River, just outside Metz. Patton expected that the theater commander would keep fuel and supplies flowing to support successful advances, but Eisenhower favored a "broad front" approach to the ground-war effort, believing that a single thrust would have to drop off flank protection, and would quickly lose its punch. Still within the constraints of a very large effort overall, Eisenhower gave Montgomery and his Twenty First Army Group a higher priority for supplies for Operation Market Garden.[144] Combined with other demands on the limited resource pool, the Third Army exhausted its fuel supplies.[145] Patton believed his forces were close enough to the Siegfried Line that he remarked to Bradley that with 400,000 gallons of gasoline he could be in Germany within two days.[146] In late September, a large German Panzer counterattack sent expressly to stop the advance of Patton's Third Army was defeated by the U.S. 4th Armored Division at the Battle of Arracourt. Despite the victory, the Third Army stayed in place as a result of Eisenhower's order. The German commanders believed this was because their counterattack had been successful.[147]

The halt of the Third Army during the month of September was enough to allow the Germans to strengthen the fortress of Metz. In October and November, the Third Army was mired in a near-stalemate with the Germans during the Battle of Metz, both sides suffering heavy casualties. An attempt by Patton to seize Fort Driant just south of Metz was defeated, but by mid-November Metz had fallen to the Americans.[148] Patton's decisions in taking this city were criticized. German commanders interviewed after the war noted he could have bypassed the city and moved north to Luxembourg where he would have been able to cut off the German Seventh Army.[149] The German commander of Metz, General Hermann Balck, also noted that a more direct attack would have resulted in a more decisive Allied victory in the city. The Lorraine Campaign was one of Patton's least successful, faulting him for not deploying his divisions more aggressively and decisively.[150]

With supplies low and priority given to Montgomery until the port of Antwerp could be opened, Patton remained frustrated at the lack of progress of his forces. From November 8 to December 15, his army advanced no more than 40 miles (64 km).[151]

Battle of the Bulge

In December 1944, the German army, under the command of German Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt, launched a last-ditch offensive across Belgium, Luxembourg, and northeastern France. On December 16, 1944, it massed 29 divisions totaling 250,000 men at a weak point in the Allied lines, and during the early stages of the ensuing Battle of the Bulge, made significant headway towards the Meuse River during a severe winter. Eisenhower called a meeting of all senior Allied commanders on the Western Front at a headquarters near Verdun on the morning of December 19 to plan strategy and a response to the German assault.[152]

At the time, Patton's Third Army was engaged in heavy fighting near Saarbrücken. Guessing the intent of the Allied command meeting, Patton ordered his staff to make three separate operational contingency orders to disengage elements of the Third Army from its present position and begin offensive operations toward several objectives in the area of the bulge occupied by German forces.[153] At the Supreme Command conference, Eisenhower led the meeting, which was attended by Patton, Bradley, General Jacob Devers, Major General Kenneth Strong, Deputy Supreme Commander Air Chief Marshal Arthur Tedder, and several staff officers.[154] When Eisenhower asked Patton how long it would take him to disengage six divisions of his Third Army and commence a counterattack north to relieve the U.S. 101st Airborne Division which had been trapped at Bastogne, Patton replied, "As soon as you're through with me."[155] Patton then clarified that he had already worked up an operational order for a counterattack by three full divisions on December 21, then only 48 hours away. Eisenhower was incredulous: "Don't be fatuous, George. If you try to go that early you won't have all three divisions ready and you'll go piecemeal." Patton replied that his staff already had a contingency operations order ready to go. Still unconvinced, Eisenhower ordered Patton to attack the morning of December 22, using at least three divisions.[156]

Patton left the conference room, phoned his command, and uttered two words: "Play ball." This code phrase initiated a prearranged operational order with Patton's staff, mobilizing three divisions—the 4th Armored Division, the U.S. 80th Infantry Division, and the U.S. 26th Infantry Division—from the Third Army and moving them north toward Bastogne. In all, Patton would reposition six full divisions, U.S. III Corps and U.S. XII Corps, from their positions on the Saar River front along a line stretching from Bastogne to Diekirch and to Echternach, the town in Luxembourg that had been at the southern end of the initial "Bulge" front line on December 16.} Within a few days, more than 133,000 Third Army vehicles were rerouted into an offensive that covered an average distance of over 11 miles (18 km) per vehicle, followed by support echelons carrying 62,000 tonnes (61,000 long tons; 68,000 short tons) of supplies.[157]

On December 21, Patton met with Bradley to review the impending advance, starting the meeting by remarking, "Brad, this time the Kraut's stuck his head in the meat grinder, and I've got hold of the handle."[158] Patton then argued that his Third Army should attack toward Koblenz, cutting off the bulge at the base and trap the entirety of the German armies involved in the offensive. After briefly considering this, Bradley vetoed it, since he was less concerned about killing large numbers of Germans than he was in arranging for the relief of Bastogne before it was overrun.[159] Desiring good weather for his advance, which would permit close ground support by U.S. Army Air Forces tactical aircraft, Patton ordered the Third Army chaplain, Colonel James Hugh O'Neill, to compose a suitable prayer. He responded:

Almighty and most merciful Father, we humbly beseech Thee, of Thy great goodness, to restrain these immoderate rains with which we have had to contend. Grant us fair weather for Battle. Graciously hearken to us as soldiers who call upon Thee that, armed with Thy power, we may advance from victory to victory and crush the oppression and wickedness of our enemies, and establish Thy justice among men and nations. Amen.[160]

When the weather cleared soon after, Patton awarded O'Neill a Bronze Star Medal on the spot.

On December 26, 1944, the first spearhead units of the Third Army's 4th Armored Division reached Bastogne, opening a corridor for relief and resupply of the besieged forces. Patton's ability to disengage six divisions from front line combat during the middle of winter, then wheel north to relieve Bastogne was one of his most remarkable achievements during the war.[161] He later wrote that the relief of Bastogne was "the most brilliant operation we have thus far performed, and it is in my opinion the outstanding achievement of the war. This is my biggest battle."[162]

Advance into Germany

By February, the Germans were in full retreat. On February 23, 1945, the U.S. 94th Infantry Division crossed the Saar River and established a vital bridgehead at Serrig, through which Patton pushed units into the Saarland. Patton had insisted upon an immediate crossing of the Saar River against the advice of his officers. Historians such as Charles Whiting have criticized this strategy as unnecessarily aggressive.[163]

Once again, Patton found other commands given priority based on gasoline and supplies.[164] To obtain these, Third Army ordnance units passed themselves off as First Army personnel and in one incident they secured thousands of gallons of gasoline from a First Army dump.[165] Between January 29 and March 22, the Third Army took Trier, Coblenz, Bingen, Worms, Mainz, Kaiserslautern, and Ludwigshafen, killing or wounding 99,000 and capturing 140,112 German soldiers, which represented virtually all of the remnants of the German First and Seventh Armies. An example of Patton's sarcastic wit was broadcast when he received orders to bypass Trier, as it had been decided that four divisions would be needed to capture it. When the message arrived, Trier had already fallen. Patton rather caustically replied: "Have taken Trier with two divisions. Do you want me to give it back?"[166]

The Third Army began crossing the Rhine River after constructing a pontoon bridge on March 22, two weeks after the First Army crossed it at Remagen, and Patton slipped a division across the river that evening.[167] Patton later boasted he had urinated into the river as he crossed.[168]

On March 26, 1945, Patton sent Task Force Baum, consisting of 314 men, 16 tanks, and assorted other vehicles, 50 miles (80 km) behind German lines to liberate the prisoner of war camp OFLAG XIII-B, near Hammelburg. Patton knew that one of the inmates was his son-in-law, Lieutenant Colonel John K. Waters. The raid was a failure, and only 35 men made it back; the rest were either killed or captured, and all 57 vehicles were lost. Patton reported this attempt to liberate Oflag XIII-B as the only mistake he made during World War II.[169] When Eisenhower learned of the secret mission, he was furious.[170] Patton later said he felt the correct decision would have been to send a Combat Command, which is a force about three times larger.

By April, resistance against the Third Army was tapering off, and the forces' main efforts turned to managing some 400,000 German prisoners of war. On April 14, 1945, Patton was promoted to general, a promotion long advocated by Stimson in recognition of Patton's battle accomplishments during 1944.[171] Later that month, Patton, Bradley, and Eisenhower toured the Merkers salt mine as well as the Ohrdruf concentration camp. Seeing the conditions of the camp firsthand caused Patton great disgust. Third Army was ordered toward Bavaria and Czechoslovakia, anticipating a last stand by Nazi German forces there. He was reportedly appalled to learn that the Red Army would take Berlin, feeling that the Soviet Union was a threat to the U.S. Army's advance to Pilsen, but was stopped by Eisenhower from reaching Prague, Czechoslovakia, before V-E Day on May 8 and the end of the war in Europe.[172]

In its advance from the Rhine to the Elbe, Patton's Third Army, which numbered between 250,000 and 300,000 men at any given time, captured 32,763 square miles (84,860 km²) of German territory. Its losses were 2,102 killed, 7,954 wounded, and 1,591 missing. German losses in the fighting against the Third Army totaled 20,100 killed, 47,700 wounded, and 653,140 captured. Between becoming operational in Normandy on August 1, 1944, and the end of hostilities on May 9, 1945, the Third Army was in continuous combat for 281 days. In that time, it crossed 24 major rivers and captured 81,500 square miles (211,000 km²) of territory, including more than 12,000 cities and towns. The Third Army claimed to have killed, wounded, or captured 1,811,388 German soldiers, six times its strength in personnel.[173] Fuller's review of Third Army records differs only in the number of enemy killed and wounded, stating that between August 1, 1944, and May 9, 1945, 47,500 of the enemy were killed, 115,700 wounded, and 1,280,688 captured, for a total of 1,443,888.[174]

Postwar

Patton asked for a command in the Pacific Theater of Operations, begging Marshall to bring him to that war in any way possible. Marshall said he would be able to do so only if the Chinese secured a major port for his entry, an unlikely scenario.[175] In mid-May, Patton flew to Paris, then London for rest. On June 7, he arrived in Bedford, Massachusetts, for extended leave with his family, and was greeted by thousands of spectators. Patton then drove to Hatch Memorial Shell and spoke to some 20,000, including a crowd of 400 wounded Third Army veterans. In this speech he aroused some controversy among the Gold Star Mothers when he stated that a man who dies in battle is "frequently a fool,"[176] adding that the wounded are heroes. Patton spent time in Boston before visiting and speaking in Denver and visiting Los Angeles, where he spoke to a crowd of 100,000 at the Memorial Coliseum. Patton made a final stop in Washington, D.C. before returning to Europe in July to serve in the occupation forces.

On June 14, 1945, Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson announced that Patton would not be sent to the Pacific but would return to Europe in an occupation army assignment.[177]

Patton was appointed as military governor of Bavaria, where he led the Third Army in denazification efforts. Patton was particularly upset when learning of the end of the war against Japan, writing in his diary, "Yet another war has come to an end, and with it my usefulness to the world."[178] Unhappy with his position and depressed by his belief that he would never fight in another war, Patton's behavior and statements became increasingly erratic. Various explanations beyond his disappointments have been proposed for Patton's behavior. "[it] seems virtually inevitable ... that Patton experienced some type of brain damage from too many head injuries" from a lifetime of numerous auto- and horse-related accidents, especially one suffered while playing polo in 1936.[179]

Patton's niece Jean Gordon appeared again; they spent some time together in London in 1944, and again in Bavaria in 1945. Gordon actually loved a young married captain who left her despondent when he went home to his wife in September 1945.[180] Patton repeatedly boasted of his sexual success with Gordon, but his biographers are skeptical. Hirshson said that the relationship was casual.[181] Showalter believes that Patton, under severe physical and psychological stress, made up claims of sexual conquest to prove his virility.[182] "His behavior suggests that in both 1936 [in Hawaii] and 1944–45, the presence of the young and attractive Jean was a means of assuaging the anxieties of a middle-aged man troubled over his virility and a fear of aging."[183]

Patton attracted controversy as military governor when it was noted that several former Nazi Party members continued to hold political posts in the region.[184] When responding to the press about the subject, Patton repeatedly compared Nazis to Democrats and Republicans in noting that most of the people with experience in infrastructure management had been compelled to join the party in the war, causing negative press stateside and angering Eisenhower.[185] On September 28, 1945, after a heated exchange with Eisenhower over his statements, Patton was relieved of his military governorship. He was relieved of command of the Third Army on October 7, and in a somber change of command ceremony, Patton concluded his farewell remarks, "All good things must come to an end. The best thing that has ever happened to me thus far is the honor and privilege of having commanded the Third Army."[186]

Patton's final assignment was to command the U.S. 15th Army, based in Bad Nauheim. The 15th Army at this point consisted only of a small headquarters staff working to compile a history of the war in Europe. Patton had accepted the post because of his love of history, but quickly lost interest. He began traveling, visiting Paris, Rennes, Chartres, Brussels, Metz, Reims, Luxembourg, and Verdun. Then he went to Stockholm, where he reunited with other athletes from the 1912 Olympics. Patton decided that he would leave his post at the 15th Army and not return to Europe once he left on December 10 for Christmas leave. He intended to discuss with his wife whether he would continue in a stateside post or retire from the Army.[187]

Accident and death

On December 8, 1945, Patton's chief of staff, Major General Hobart Gay, invited him on a pheasant hunting trip near Speyer to lift his spirits. Observing derelict cars along the side of the road, Patton said, "How awful war is. Think of the waste." Moments later his car collided with an American army truck at low speed.[188]

Gay and others were only slightly injured, but Patton hit his head on the glass partition in the back seat. He began bleeding from a gash to the head, and complained that he was paralyzed and having trouble breathing. Taken to a hospital in Heidelberg, Patton was discovered to have a compression fracture and dislocation of the cervical third and fourth vertebrae, resulting in a broken neck and cervical spinal cord injury that rendered him paralyzed from the neck down.[189]

Patton spent most of the next 12 days in spinal traction to decrease the pressure on his spine. All non-medical visitors, except for Patton's wife who had flown from the U.S., were forbidden. Patton, who had been told he had no chance to ever again ride a horse or resume normal life, at one point commented, "This is a hell of a way to die." He died in his sleep of pulmonary edema and congestive heart failure at about 18:00 on December 21, 1945.[190]

Patton was buried at the Luxembourg American Cemetery and Memorial in the Hamm district of Luxembourg City, alongside some wartime casualties of the Third Army, in accordance with his request to "be buried with [his] men."[191]

Legacy

Patton's colorful personality, hard-driving leadership style, and success as a commander, combined with his frequent political missteps, produced a mixed and often contradictory image. Patton's great oratory skill is seen as integral to his ability to inspire troops under his command.[192] Historian Terry Brighton concluded that Patton was "arrogant, publicity-seeking and personally flawed, but ... among the greatest generals of the war".[193] Patton's impact on armored warfare and leadership were substantial, with the U.S. Army's adopting many of Patton's aggressive strategies for its training programs following his death. Many military officers claim inspiration from his legacy. The first American tank designed after the war became the M46 Patton.[194]

Image

Patton cultivated a flashy, distinctive image in the belief that this would inspire his troops. He carried an ivory-gripped, engraved, silver-plated Colt Single Action Army .45 caliber revolver on his right hip, and frequently wore an ivory-gripped Smith & Wesson Model 27 .357 Magnum on his left hip.[195] He was usually seen wearing a highly polished helmet, riding pants, and high cavalry boots.[196] Patton also cultivated a stern expression he called his "war face."[197] He was known to oversee training maneuvers from atop a tank painted red, white and blue. His jeep bore oversized rank placards on the front and back, as well as a klaxon horn which would loudly announce his approach from afar. He proposed a new uniform for the emerging Tank Corps, featuring polished buttons, a gold helmet, and thick, dark padded suits; the proposal was derided in the media as "the Green Hornet," and rejected by the Army.[198]

The historian Alan Axelrod wrote that "for Patton, leadership was never simply about making plans and giving orders, it was about transforming oneself into a symbol."[199] Patton intentionally expressed a conspicuous desire for glory, atypical of the officer corps of the day which emphasized blending in with troops on the battlefield. He was an admirer of Admiral Horatio Nelson for his actions in leading the Battle of Trafalgar in a full dress uniform. Patton had a preoccupation with bravery,[200] wearing his rank insignia conspicuously in combat, and at one point during World War II, he rode atop a tank into a German-controlled village seeking to inspire courage in his men.[201]

Patton was a staunch fatalist, and he believed in reincarnation. He believed that he might have been a military leader killed in action in Napoleon's army or a Roman legionary in a previous life.[202]

Patton developed an ability to deliver charismatic speeches.[203] He used profanity heavily in his speech, which generally was enjoyed by troops under his command, but it offended other generals, including Bradley.[204] The most famous of his speeches were a series he delivered to the Third Army prior to Operation Overlord.[205] When speaking, he was known for his bluntness and witticism; he once said, "The two most dangerous weapons the Germans have are our own armored halftrack and jeep. The halftrack because the boys in it go all heroic, thinking they are in a tank. The jeep because we have so many God-awful drivers."[206] During the Battle of the Bulge, he famously remarked that the Allies should "let the sons-of-bitches [Germans] go all the way to Paris, then we'll cut them off and round them up." He also suggested facetiously that his Third Army could "drive the British back into the sea for another Dunkirk."[207]

As a leader, Patton was known to be highly critical, correcting subordinates mercilessly for the slightest infractions, but also being quick to praise their accomplishments.[208] Although he garnered a reputation as a general who was both impatient and impulsive and had little tolerance for officers who had failed to succeed, he fired only one general during World War II, Orlando Ward, and only after two warnings, whereas Bradley sacked several generals during the war.[209] Patton reportedly had the utmost respect for the men serving in his command, particularly the wounded.[210] Many of his directives showed special trouble to care for the enlisted men under his command, and he was well known for arranging extra supplies for battlefield soldiers, including blankets and extra socks, galoshes, and other items normally in short supply at the front.[211]

Several actors have portrayed Patton on screen, including George C. Scott in the 1970 film Patton. Scott's iconic depiction of Patton earned him an Academy Award for Best Actor, and was instrumental in bringing Patton into popular culture as a folk hero.[212] He would reprise the role in 1986 in the made-for-television film The Last Days of Patton.[213]

As viewed by Allied and Axis leaders

On February 1, 1945, Eisenhower wrote a memo ranking the military capabilities of his subordinate American generals in Europe. General Bradley and the Army Air Forces General Carl Spaatz shared the number one position, Walter Bedell Smith was ranked number three, and Patton number four.[214] Eisenhower revealed his reasoning in a 1946 review of the book Patton and His Third Army: "George Patton was the most brilliant commander of an Army in the open field that our or any other service produced. But his army was part of a whole organization and his operations part of a great campaign."[215] Eisenhower believed that other generals such as Bradley should be given the credit for planning the successful Allied campaigns across Europe in which Patton was merely "a brilliant executor."

Notwithstanding Eisenhower's estimation of Patton's abilities as a strategic planner, his overall view of Patton's military value in achieving Allied victory in Europe is revealed in his refusal to even consider sending Patton home after the slapping incidents of 1943, after which he privately remarked, "Patton is indispensable to the war effort—one of the guarantors of our victory."[216] As Assistant Secretary of War John J. McCloy told Eisenhower: "Lincoln's remark after they got after Grant comes to mind when I think of Patton—'I can't spare this man, he fights'."[217] After Patton's death, Eisenhower would write his own tribute: "He was one of those men born to be a soldier, an ideal combat leader ... It is no exaggeration to say that Patton's name struck terror at the hearts of the enemy."[218]

Historian Carlo D'Este insisted that Bradley disliked Patton both personally and professionally,[219][220] but Bradley's biographer Jim DeFelice noted that the evidence indicates otherwise.[221] President Franklin D. Roosevelt appeared to greatly esteem Patton and his abilities, stating "he is our greatest fighting general, and sheer joy."[222] On the other hand, Roosevelt's successor, Harry S. Truman, appears to have taken an instant dislike to Patton, at one point comparing both him and Douglas MacArthur to George Armstrong Custer.

For the most part, British commanders did not hold Patton in high regard. One exception was Field Marshal Sir Bernard Montgomery who appears to have admired Patton's ability to command troops in the field, if not his strategic judgment.[223] Other Allied commanders were more impressed, the Free French in particular. General Henri Giraud was incredulous when he heard of Patton's dismissal by Eisenhower in late 1945, and invited him to Paris to be decorated by French President, Charles de Gaulle, at a state banquet. At the banquet, President de Gaulle gave a speech placing Patton's achievements alongside those of Napoleon.[224] Soviet leader Joseph Stalin was apparently an admirer, stating that the Red Army could neither have planned nor executed Patton's rapid armored advance across France.[225]

While Allied leaders expressed mixed feelings on Patton's capabilities, the German High Command was noted to have more respect for him than for any other Allied commander after 1943.[226] Adolf Hitler reportedly called him "that crazy cowboy general."[227] Many German field commanders were generous in their praise of Patton's leadership following the war. Among the opinions of Patton's abilities, Oberstleutnant Horst Freiherr von Wangenheim, operations officer of the 277th Volksgrenadier Division, stated that "General Patton is the most feared general on all fronts. [His] tactics are daring and unpredictable .... He is the most modern general and the best commander of [combined] armored and infantry forces."[228] General der Panzertruppen Hasso von Manteuffel, who had fought both Soviet and Anglo-American tank commanders, agreed: "Patton! No doubt about this. He was a brilliant Panzer army commander."[229] and many of its highest commanders also held his abilities in high regard. Erwin Rommel credited Patton with executing "the most astonishing achievement in mobile warfare."[230] In an interview conducted for Stars and Stripes just after his capture, Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt stated simply of Patton, "He is your best."[231]

Notes

- ↑ Terry Brighton, Patton, Montgomery, Rommel: Masters of War (New York, NY: Crown Publishing Group, 2009, ISBN 978-0307461544), 17.

- ↑ Alan Axelrod, Patton: A Biography (London, England: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006, ISBN 978-0230613928), 11–12.

- ↑ Axelrod, 11–12.

- ↑ Axelrod, 13.

- ↑ Axelrod, 28, 35, 65–66.

- ↑ Ladislas Farago, The Last Days of Patton (Yardley, PA: Westholme Publishing LLC, 2011, ISBN 1594161380), 310.

- ↑ Axelrod, 13.

- ↑ Axelrod, 14–15.

- ↑ Martin Blumenson, The Patton Papers: 1885–1940 (Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1972, ISBN 978-0395127063), 92.

- ↑ George S. Patton, Jr. Distinguished Achievement Award Kappa Alpha Order. Retrieved November 7, 2021.

- ↑ Steven Zaloga, George S. Patton: Leadership, Strategy, Conflict (Oxford, United Kingdom: Osprey Publishing, 2010, ISBN 1846034590), 7.

- ↑ Axelrod, 20–23.

- ↑ Brighton, 19.

- ↑ Carlo D'Este, Patton: A Genius for War (New York, NY: Harper Collins, 1995, ISBN 978-0060164553), 58, 131.

- ↑ Axelrod, 13.

- ↑ Editors of the Army Times, Warrior: The Story of General George Patton, Jr. (New York, NY, G.P. Putnam's Sons, 1967), 15.

- ↑ Michael Keane, George S. Patton: Blood, Guts, and Prayer (Washington, DC: Regnery Publishing, 2014, ISBN 978-1621572985), 84.

- ↑ Earl Rice, George S. Patton (Topeka, KS: Tandem Library Group, 2004), 32.

- ↑ J. Furman Daniel III (ed.), 21st Century Patton: Strategic Insights for the Modern Era (Naval Institute Press, 2016, ISBN 978-1682470633), 61.

- ↑ D'Este 1995, 9.

- ↑ Zaloga, 2010, 6.

- ↑ Robert H. Patton, The Pattons: A Personal History of an American Family (Sterling, VA: Potomac Books, Inc., 2004, ISBN 978-1574886900), 3–5.

- ↑ Brighton, 20.

- ↑ Axelrod, 26–27.

- ↑ Axelrod, 28–29.

- ↑ Zaloga, 2010, 8.

- ↑ Axelrod, 30.

- ↑ D'Este, 1995, 132-134.

- ↑ Blumenson, 1972, 231–234.

- ↑ D'Este, 1995, 140–142.

- ↑ D'Este, 1995, 145.

- ↑ Brighton, 21.

- ↑ Axelrod, 33–34.

- ↑ D'Este, 1995, 153.

- ↑ Axelrod, 35.

- ↑ D'Este, 1995, 148.

- ↑ D'Este, 1995, 158–159.

- ↑ Zaloga, 2010, 9.

- ↑ Zaloga, 2010, 10.

- ↑ D'Este, 1995, 165.

- ↑ Brighton, 31.

- ↑ Axelrod, 38–39.

- ↑ Philip Jowett and Alejandro de Quesada, The Mexican Revolution 1910–20 (London, England: Osprey Publishing, 2006, ISBN 978-1841769899), 25.

- ↑ Axelrod, 40.

- ↑ Axelrod, 41–42.

- ↑ D'Este, 1995, 172–175.

- ↑ Zaloga, 2010, 10.

- ↑ Axelrod, 36.

- ↑ Axelrod, 43.

- ↑ Axelrod, 46.

- ↑ Zaloga, 2010, 10.

- ↑ Axelrod, 47–48.

- ↑ Axelrod, 49.

- ↑ Zaloga, 2010, 10.

- ↑ D'Este, 1995, 204–208.

- ↑ Blumenson, 1972, 480–483.

- ↑ Axelrod, 49.

- ↑ Blumenson, 1972, 552–553.

- ↑ Axelrod, 50–52.

- ↑ Axelrod, 53.

- ↑ Blumenson, 1972, 661–670.

- ↑ Brighton, 38.

- ↑ Blumenson, 1972, 706–708.

- ↑ Axelrod, 54–55.

- ↑ Blumenson, 1972, 706–708.

- ↑ Brighton, 40.

- ↑ Blumenson, 1972, 764–766.

- ↑ Peter Hart, The Last Battle: Endgame on the Western Front, 1918 (London, UK: Profile Books, Ltd., 2018, ISBN 978-1781254820), 67.

- ↑ James H. Hallas, Doughboy War: The American Expeditionary Force in WWI (Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 2009, ISBN 978-0811734677), 245–246.

- ↑ Martin Blumenson, The Patton Papers: 1940–1945 (Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin, 1974, 978-0395184981), 616.

- ↑ Axelrod, 58–59.

- ↑ Axelrod, 62.

- ↑ Axelrod, 63–64.

- ↑ Brighton, 46.

- ↑ Axelrod, 65–66.

- ↑ Brett D. Steele, Military Reengineering Between the World Wars (Chicago, IL: Rand Publishing, 2005, ISBN 978-0833037213), 18.

- ↑ Axelrod, 63–64.

- ↑ "Veterans of Great War," The Evening Star, July 17, 1921, p. 20. Chronicling America. Retrieved November 7, 2021.

- ↑ Brighton, 57.

- ↑ D'Este, 1995, 335.

- ↑ Axelrod, 65–66.

- ↑ Axelrod, 67–68.

- ↑ Brighton, 58–59.

- ↑ Thomas Allen and Paul Dickson, The Bonus Army: An American Epic (London, England: Walker & Company, 2006, ISBN 978-0802777386), 194.

- ↑ D'Este, 1995, 361.

- ↑ Brighton, 379–380.

- ↑ Axelrod, 71–72.

- ↑ Axelrod, 73–74.

- ↑ "Storied Schooner Once Owned by General Patton to be Sold," The Vineyard Gazette – Martha's Vineyard News, September 23, 2010. Retrieved November 7, 2021.

- ↑ Brighton, 82–83.

- ↑ Axelrod, 75–76.

- ↑ Brighton, 85.

- ↑ Axelrod, 77–79.

- ↑ Brighton, 106.

- ↑ Axelrod, 80–82.

- ↑ Axelrod, 83.

- ↑ Axelrod, 84–85.

- ↑ Blumenson, 1974, 542.

- ↑ Alexander G. Lovelace, "The Image of a General: The Wartime Relationship between General George S. Patton Jr. and the American Media," Journalism History 40(2), (Summer 2014), 110.

- ↑ Axelrod, 2.

- ↑ Brighton, 117–119.

- ↑ Brighton, 165–166.

- ↑ Maitland A. Edey, Time Capsule 1943 (London, England: Littlehampton Book Services, 1968, ISBN 978-0705402705), 60.

- ↑ Axelrod, 94.

- ↑ Martin Blumenson, Patton: The Man Behind the Legend. New York, NY: William Morrow and Company, 1985, ISBN 978-0688137953), 182.

- ↑ David Hunt, A Don at War (London, England: Frank Cass, 1990, (1966), ISBN 978-0714633831), 169.

- ↑ Axelrod, 96–97.

- ↑ Axelrod, 98–99.

- ↑ Brighton, 188.

- ↑ Axelrod, 101–104.

- ↑ Brighton, 201–202.

- ↑ Axelrod, 105–107.

- ↑ Axelrod, 108–109.

- ↑ Brighton, 215.

- ↑ D'Este, 1995, 466.

- ↑ Axelrod, 105–107.

- ↑ Rick Atkinson, The Day of Battle: The War in Sicily and Italy, 1943–1944 (The Liberation Trilogy) (New York, NY: Henry Holt and Company, 2008, ISBN 978-0805088618), 119.

- ↑ Atkinson, 119.

- ↑ Blumenson, 1974, 331.

- ↑ Axelrod, 117-118.

- ↑ Blumenson, 1974, 329, 336, 338.

- ↑ D'Este, 1995, 535–536.

- ↑ Axelrod, 120.

- ↑ Edey, 160–166.

- ↑ Blumenson, 1974, 377.

- ↑ D'Este, 1995, 543.

- ↑ Axelrod, 122.

- ↑ Blumenson, 1974, 345.

- ↑ Axelrod, 121.

- ↑ Blumenson, 1974, 348.

- ↑ Blumenson, 1974, 407.

- ↑ Axelrod, 127.

- ↑ Blumenson, 1974, 409.

- ↑ Axelrod, 127-128.

- ↑ Axelrod, 132.

- ↑ Hubert Essame, Patton: A Study in Command (New York, NY: Scribner & Sons, 1974, ISBN 978-0684136714), 178.

- ↑ Axelrod, 135–136, 139–140.

- ↑ Axelrod, 137.

- ↑ Roman J. Jarymowycz, Tank tactics: from Normandy to Lorraine (Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner Publishers, 2001, ISBN 1555879500), 212, 215-216.

- ↑ Ian Gooderson, Air Power at the Battlefront: Allied Close Air Support in Europe 1943–45 (Portland, OR: Routledge, 1998, ISBN 978-0714642116), 44.

- ↑ Gooderson, 85.

- ↑ Axelrod, 138.

- ↑ Jarymowycz, 217.

- ↑ Stephen E. Ambrose, Eisenhower: Soldier and President (New York, NY: Simon & Schuster, 2007, ISBN 978-0945707394), 162–164.

- ↑ Steven Zaloga, Armored Thunderbolt: The U.S. Army Sherman in World War II (Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 2008, ISBN 978-0811704243), 184–193.

- ↑ Axelrod, 141.

- ↑ Frederich W. von Mellenthin, Panzer Battles: A Study of the Employment of Armor in the Second World War (Old Saybrook, CT: Konecky & Konecky, 2006, ISBN 978-1568525785), 381–382.

- ↑ Axelrod, 142.

- ↑ Stanley Hirshson, General Patton: A Soldier's Life (New York, NY: Harper Perennial, 2003, ISBN 978-0060009830), 546.

- ↑ D'Este, 1995, 669.

- ↑ Axelrod, 143–144.

- ↑ D'Este, 1995, 675–678.

- ↑ Tim McNeese, Great Battles through the Ages: Battle of the Bulge (New York, NY: Chelsea House Publications, 2003, ISBN 978-0791074350), 77.

- ↑ Blumenson, 1974, 599.

- ↑ McNeese, 75.

- ↑ Axelrod, 148–149.

- ↑ McNeese, 77-79.

- ↑ McNeese, 77.

- ↑ Axelrod, 148–149.

- ↑ D'Este, 1995, 535–536.

- ↑ Axelrod, 152–153.

- ↑ McNeese, 79.

- ↑ Tony Le Tissier, Patton's Pawns: The 94th US Infantry Division at the Siegfried Line (Tuscaloosa, AL: University of Alabama Press, 2007, ISBN 978-0817315573), 147–155.