Peking Man

| Peking Man

| ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

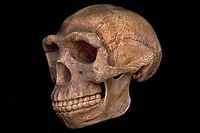

Peking Man skull

| ||||||||||||||||||

| Scientific classification | ||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||

| Homo erectus pekinensis (Black, 1927) |

Peking Man (sometimes called Beijing Man), is a prominent example of Homo erectus, an extinct species of the genus to which modern humans also belong. Peking Man was originally called Sinanthropus pekinensis and currently is best known as Homo erectus pekinensis. The remains were first discovered in 1921-1927 during excavations at Zhoukoudian (Choukoutien) near Beijing (former Peking), China. The finds have been dated from roughly 250,000-400,000 years ago in the Pleistocene.

Fossils of Homo erectus also have been found in Africa, Indonesia, and Georgia (Caucasus region of Europe). Although Homo erectus has been placed from about 1.8 million years ago (mya) to 50-70,000 years ago, the early phase in Africa, from 1.8 to 1.25 (or 1.6) mya, often is either considered to be a separate species, Homo ergaster, or it is seen as a subspecies of erectus, Homo erectus ergaster (Mayr 2001). That is, those populations in Asia, including Peking Man, differ enough from the early populations of H. erectus in Africa that many consider the mainly Asian populations H. erectus and the early African populations as H. ergaster or H. erectus ergaster (Smithsonian 2007a).

H. erectus is considered to be the first hominid to spread out of Africa and the first human ancestor to walk truly upright.

The fragmentary nature of the hominid fossil record, and the often speculative nature of interpretations, is exemplified by the fact that the new species Sinanthropus pekinensis was originally described from a single tooth, and although numerous other finds later were unearthed in China, these were lost during World War II. Subsequent inferences have come from casts and descriptions of the original fossils.

Although H. erectus was originally believed to have disappeared roughly 400,000 years ago, the dating of deposits thought to contain H. erectus fossils in Java were placed at only 50,000 years ago, meaning that at least one population would have been a contemporary of modern humans (Smithsonian 2007b).

Homo erectus served as a foundation for subsequent stages in human evolution, and the African population, rather than the Asian population, is considered to have given rise to Neandertals and Homo sapiens (Mayr 2001).

History of fossil findings

The first specimens of Homo erectus had been found on the Indonesian island of Java in 1891 by Eugene Dubois. Java Man initially was designated Pithecanthropus erectus, but was later transferred to the genus Homo.

In China, the first fossil findings began at Zhoukoudian in 1921 with an investigation of a number of caves in the limestone there. According to later accounts of Otto Zdansky, who was working for geologist Johan Gunnar Andersson, a local man lead western archaeologists to what is today known as the Dragon Bone Hill, a place full of fossilized bones. Zdansky began his own excavation and eventually found bones that resembled human molars. In 1926, he took them to the Peking Union Medical College, in Peking, where Canadian anatomist Davidson Black analyzed them. Based on Black's analysis of a single tooth, a lower molar, the species was dubbed Sinanthropus pekinensis. Black published his finding in the journal Nature.

Much of the early and spectacular discovery of H. erectus took place at Zhoukoudian in China. The Rockefeller Foundation agreed to fund the work at Zhoukoudian. By 1929, Chinese archaeologists Yang Zhongjian and Pei Wenzhong, and later Jia Lanpo, had taken over the excavation. Over the next seven years, they uncovered fossils of more than 40 specimens, including 6 nearly complete skullcaps. Pierre Teilhard de Chardin and Franz Weidenreich were also involved.

Excavation ended in July 1937 when the Japanese occupied Beijing. Fossils of the Peking Man were placed in the safe at the Cenozoic Laboratory of the Peking Union Medical College. Eventually, in November 1941, secretary Hu Chengzi packed up the fossils so they could be sent to United States for safekeeping until the end of the war. They vanished en route to the port city of Qinghuangdao. They were probably in possession of a group of United States marines who the Japanese captured when the war began between Japan and America.

Various parties have tried to locate the fossils but without result. In 1972, U.S. financier Christopher Janus promised a $5,000 (U.S.) reward for the missing skulls; one woman contacted him, asking for $500,000 (U.S.) but she later vanished. Janus was later indicted for embezzlement. In July 2005, the Chinese government founded a committee to find the bones to coincide with the 60th anniversary of the end of World War II.

There are also various theories of what might have happened, including a theory that the bones had sunk with the Japanese ship Awa Maru in 1945.

German anatomist Franz Weidenreich provided much of the detail descriptions of this material in several monographs published in the journal Palaeontologica Sinica (Series D). High quality Weidenreichian casts do exist and are considered to be reliable evidence; these are curated at the American Museum of Natural History (NYC) and at the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology (Beijing).

The Peking Man Site at Zhoukoudian was listed by UNESCO as a World Heritage Site in 1987.

Paleontological conclusions

Because all the pre-war findings at Zhoukoudian were lost during transit to the United States, subsequent researchers have had to rely on casts and existing writings from the original discoverers.

Contiguous findings of animal remains and evidence of fire and tool usage, as well as the manufacturing of tools, were used to support H. erectus being the first "faber" or tool-worker. This interpretation was challenged in 1985 by Lewis Binford, who claimed that the Peking Man was a scavenger, not a hunter. The 1998 team of Steve Weiner of the Weizmann Institute of Science concluded that they had not found evidence that the Peking Man had used fire.

The analysis of the remains of "Peking Man" led to the claim that the Zhoukoudian and Java fossils are examples of the same broad stage of human evolution.

Among the world's most well-known fossils, Peking Man is popularly presented in works of fiction, such as Philip K. Dick's The Crack in Space, Carolyn G. Hart's Skulduggery, Robert Sawyer's short story "Peking Man," Katherine V. Forrest's Sleeping Bones, Nicole Mone's Lost in Translation, and referred to in Amy Tan's The Bonesetter's Daughter.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Hooker, J. 2006. The Search for Peking Man. Archaeology 59(2).

- Kreger, C. D. 2005. Homo erectus: Introduction. Archaeology.info.

- Mayr, E. 2001. What evolution is. New York: Basic Books. ISBN 0465044255

- Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History. 2007a. Homo erectus. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved March 4, 2007.

- Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History. 2007b. Homo erectus. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved March 4, 2007.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.