Pelé

| Pelé | |

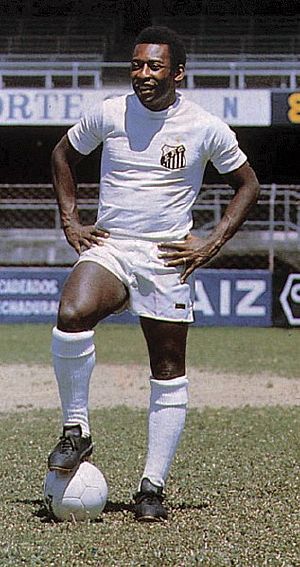

Pelé with Brazil in 1970

| |

| Born | Edson Arantes do Nascimento October 23 1940[1] Três Corações, Brazil |

|---|---|

| Died | December 29 2022 (aged 82) São Paulo, Brazil |

| Resting place | Memorial Necrópole Ecumênica, Santos, São Paulo |

| Occupation | Footballer, humanitarian |

| Height | 1.73 m |

| Spouse(s) | Rosemeri dos Reis Cholbi (m. 1966; div. 1982) Assíria Lemos Seixas (m. 2016) |

| Children | 7, including Edinho and Joshua Nascimento |

| Relatives | Zoca (brother) |

| Signature | |

Edson Arantes do Nascimento (Brazilian Portuguese: [ˈɛtsõ aˈɾɐ̃tʃiz du nasiˈmẽtu]; October 23, 1940 – December 29, 2022), better known by his nickname Pelé (Portuguese pronunciation: [peˈlɛ]), was a Brazilian professional footballer who played as a forward. Widely regarded as one of the greatest players of all time, he was among the most successful and popular sports figures of the twentieth century. His 1,279 goals in 1,363 games, which includes friendlies, is recognized as a Guinness World Record.

Averaging almost a goal per game throughout his career, Pelé was adept at striking the ball with either foot in addition to anticipating his opponents' movements on the field. Credited with connecting the phrase "The Beautiful Game" with football, Pelé's electrifying play and ability to score spectacular goals made him a star around the world. After retiring in 1977, Pelé was a worldwide ambassador for football and made many acting and commercial ventures.

In Brazil, he was hailed as a national hero for his accomplishments in football and for his outspoken support of policies that improve the social conditions of the poor. His emergence at the 1958 World Cup, where he became a black global sporting star, was a source of inspiration. Throughout his career and in his retirement, Pelé received numerous individual and team awards for his performance on the field, his record-breaking achievements, and his legacy in the sport which he changed forever.

Life

Early years

Pelé was born Edson Arantes do Nascimento on October 23, 1940 in Três Corações, Minas Gerais, the son of Fluminense footballer Dondinho (born João Ramos do Nascimento) and Celeste Arantes. He was the elder of two siblings,[2] with brother Zoca also playing for Santos, albeit not as successfully. He was named after the American inventor Thomas Edison. His parents decided to remove the "i" and call him "Edson," but there was a typo on his birth certificate, leading many documents to show his name as "Edison," not "Edson," as he was called.[3]

He was originally nicknamed "Dico" by his family.[2][4] He received the nickname "Pelé" during his school days, when, it is claimed, he was given it because of his mispronunciation of the name of his favorite player, local Vasco da Gama goalkeeper Bilé, but the more he complained the more it stuck. In his autobiography, Pelé stated he had no idea what the name means, nor did his old friends.[2] Pelé presumed that it was an insult since the word had no meaning in Portuguese. He discovered in the 2000s that the word meant "miracle" in Hebrew.[5]

Pelé grew up in poverty in Bauru in the state of São Paulo. He earned extra money by working in tea shops as a servant. Taught to play by his father, he could not afford a proper football and usually played with either a sock stuffed with newspaper and tied with string or a grapefruit.[2] He played for several amateur teams in his youth, and led Bauru Atlético Clube juniors (coached by Waldemar de Brito) to two São Paulo state youth championships. In his mid-teens, he played for an indoor football team called Radium. Indoor football had just become popular in Bauru when Pelé began playing it. He was part of the first futsal (indoor football) competition in the region. Pelé and his team won the first championship and several others.[6]

According to Pelé, futsal (indoor football) presented difficult challenges: he said it was a lot quicker than football on the grass, and that players were required to think faster because everyone is close to each other in the pitch. Pelé credits futsal for helping him think better on the spot. In addition, futsal allowed him to play with adults when he was about 14 years old. In one of the tournaments he participated in, he was initially considered too young to play, but eventually went on to end up top scorer with 14 or 15 goals. "That gave me a lot of confidence," Pelé said, "I knew then not to be afraid of whatever might come."[6]

Relationships and children

Pelé married three times and had several affairs, fathering seven children in all.

Sandra Machado was born from an affair Pelé had in 1964 with a housemaid, Anizia Machado. She fought for years to be acknowledged by Pelé, and to use his name.[7]

In 1966, Pelé married Rosemeri dos Reis Cholbi. They had two daughters, Kely Cristina (born January 13,1967), who married Arthur DeLuca, and Jennifer (b. 1978), as well as one son, Edson ("Edinho", b. August 27, 1970).[8] The couple divorced in 1982.

Pelé's daughter, Flávia Arantes do Nascimento, was born on January 6, 1970, the daughter of Lenita Kurtz; Pelé was still married to his first wife. Flavia was raised in Porto Alegre by her mother and stepfather, Juarez Carvalho. It was only at the age of 17 that she learned the true story about her biological father.[9]

From 1981 to 1986, Pelé was romantically linked with TV presenter Xuxa.

In April 1994, Pelé married psychologist and gospel singer Assíria Lemos Seixas, who gave birth on September 28, 1996 to twins Joshua and Celeste through fertility treatments. The couple divorced in 2008.[8]

At the age of 73, Pelé announced his intention to marry 41-year-old Marcia Aoki, a Japanese-Brazilian importer of medical equipment from Penápolis, São Paulo, whom he had been dating since 2010. They married in July 2016.[10]

Health

In November 2012, Pelé underwent a successful hip operation. In December 2017, Pelé appeared in a wheelchair at the 2018 World Cup draw in Moscow where he was pictured with President Vladimir Putin and Argentine footballer Diego Maradona. A month later, he collapsed from exhaustion and was taken to hospital.[11] In February 2020, his son Edinho reported that Pelé was unable to walk independently and reluctant to leave home, ascribing his condition to a lack of rehabilitation following his hip operation.[12]

In September 2021, Pelé had surgery to remove a tumor on the right side of his colon.[13] He was released on September 30, 2021 to begin chemotherapy.[14]

In early 2022, metastasis were detected in the intestine, lung, and liver. On November 29, he was admitted to the Albert Einstein Israelite Hospital in São Paulo due to a respiratory infection after he contracted COVID-19 and for reassessment of the treatment of his colon cancer.[15]

Death

In December, 2022, it was reported that Pelé had become unresponsive to chemotherapy and that it was replaced with palliative care. On December 21, 2022, the Albert Einstein Israelite Hospital, where Pelé was being treated, stated that his tumor had advanced and he required "greater care related to renal and cardiac dysfunctions."[16] Therefore, he was not allowed to spend Christmas at home, as his family had wanted.

Pelé died on December 29, 2022, at 3:27 pm, at the age of 82, due to multiple organ failure, a complication of colon cancer.[17] Pelé was buried at the Memorial Necrópole Ecumênica.[18]

Club career

Santos

1956–1962

In 1956, coach de Brito took Pelé to Santos, an industrial and port city located near São Paulo, to try out for professional club Santos FC, telling the club's directors that the 15-year-old would be "the greatest football player in the world."[20] Pelé impressed Santos coach Lula during his trial at the Estádio Vila Belmiro, and he signed a professional contract with the club in June 1956.[21] Pelé was highly promoted in the local media as a future superstar. He made his senior team debut on September 7, 1956 at the age of 15 against Corinthians de Santo André and had an impressive performance in a 7–1 victory, scoring the first goal in his prolific career during the match.

When the 1957 season started, Pelé was given a starting place in the first team and, at the age of 16, became the top scorer in the league. Ten months after signing professionally, the teenager was called up to the Brazil national team. After the 1958 and the 1962 World Cup, wealthy European clubs, such as Real Madrid, Juventus, and Manchester United, tried to sign him in vain. In 1961 the government of Brazil under President Jânio Quadros declared Pelé an "official national treasure" to prevent him from being transferred out of the country.[22]

Pelé won his first major title with Santos in 1958 as the team won the Campeonato Paulista; he would finish the tournament as the top scorer, with 58 goals, a record that still stands today. A year later, he would help the team earn their first victory in the Torneio Rio-São Paulo with a 3–0 over Vasco da Gama. However, Santos was unable to retain the Paulista title. In 1960, Pelé scored 33 goals to help his team regain the Campeonato Paulista trophy but lost out on the Rio-São Paulo tournament after finishing in 8th place. In the 1960 season, Pelé scored 47 goals and helped Santos regain the Campeonato Paulista. The club went on to win the Taça Brasil that same year, beating Bahia in the finals; Pelé finished as the top scorer of the tournament with nine goals. The victory allowed Santos to participate in the Copa Libertadores, the most prestigious club tournament in the Western hemisphere.[23]

1962–1965

| "I arrived hoping to stop a great man, but I went away convinced I had been undone by someone who was not born on the same planet as the rest of us." ——Benfica goalkeeper Costa Pereira following the loss to Santos in 1962.[24] |

Santos's most successful Copa Libertadores season started in 1962. Pelé scored twice in the playoff match to secure the first title for a Brazilian club.[25] Pelé finished as the second top scorer of the competition with four goals. That same year, Santos would successfully defend the Campeonato Paulista (with 37 goals from Pelé) and the Taça Brasil (Pelé scoring four goals in the final series against Botafogo). Santos would also win the 1962 Intercontinental Cup against Benfica. Wearing his number 10 shirt, Pelé produced one of the best performances of his career, scoring a hat-trick in Lisbon as Santos won 5–2.[26]

In March 1961, Pelé scored the gol de placa (goal worthy of a plaque), against Fluminense at the Maracanã. Pelé received the ball on the edge of his own penalty area, and ran the length of the field, eluding opposition players with feints, before striking the ball beyond the goalkeeper. A plaque was commissioned with a dedication to "the most beautiful goal in the history of the Maracanã."[27]

As the defending champions, Santos qualified automatically to the semi-final stage of the 1963 Copa Libertadores. Santos became the first Brazilian team to lift the Copa Libertadores in Argentine soil. Pelé finished the tournament with five goals. Santos lost the Campeonato Paulista after finishing in third place but went on to win the Rio-São Paulo tournament after a 0–3 win over Flamengo in the final, with Pelé scoring one goal. Pelé would also help Santos retain the Intercontinental Cup and the Taça Brasil against AC Milan and Bahia respectively.[26]

In the 1964 Copa Libertadores, Santos was beaten in both legs of the semi-finals by Independiente. The club won the Campeonato Paulista, with Pelé netting 34 goals. Santos also shared the Rio-São Paulo title with Botafogo and won the Taça Brasil for the fourth consecutive year. Although Santos lost in the semi-finals of the 1965 Copa Libertadores, Pelé finished as the top scorer of the tournament with eight goals.[28]

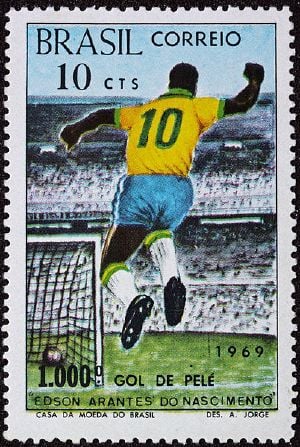

1966–1974

In 1966, Santos failed to retain the Taça Brasil. The club did, however, win the Campeonato Paulista in 1967, 1968, and 1969. On November 19, 1969, Pelé scored his 1,000th goal in all competitions, in what was a highly anticipated moment in Brazil. The goal dubbed O Milésimo (The Thousandth), occurred in a match against Vasco da Gama, when Pelé scored from a penalty kick, at the Maracanã Stadium.[29]

In 1969, the two factions involved in the Nigerian Civil War agreed to a 48-hour ceasefire so they could watch Pelé play an exhibition game in Lagos. Santos ended up playing to a 2–2 draw with Lagos side Stationary Stores FC and Pelé scored his team's goals. The civil war went on for one more year after this game, but they stopped fighting to watch Pelé play:

When Pelé asked about the likelihood of a friendly match the club’s business manager replied, “Don’t worry. They’ll stop the war. It won’t be a problem.” ... after the match Pelé wrote, “My teammates remember seeing white flags and posters saying there would be peace just to see Pelé play.”[30]

After Pelé's nineteenth season with Santos, after scoring 643 goals for the club which was a record at the time, he retired from football. However, he later came out of retirement to play in the United States.[31]

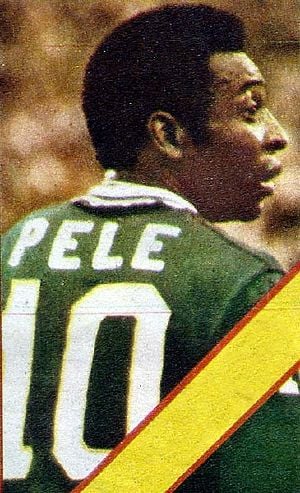

New York Cosmos

After the 1974 season (his 19th with Santos), Pelé retired from Brazilian club football although he continued to occasionally play for Santos in official competitive matches. A year later, he came out of semi-retirement to sign with the New York Cosmos of the North American Soccer League (NASL) for the 1975 season.

Pelé made his debut for the Cosmos on June 15, 1975 against the Dallas Tornado at Downing Stadium, scoring one goal in a 2–2 draw.[32] Though well past his prime at this point, Pelé was credited with significantly increasing public awareness and interest in the sport in the US. Pelé opened the door for many other stars to play in North America. Giorgio Chinaglia followed him to the Cosmos, then Franz Beckenbauer and his former Santos teammate Carlos Alberto. Over the next few years other players came to the league, including Johan Cruyff, Eusébio, Bobby Moore, George Best and Gordon Banks.[33]

Pelé led the Cosmos to the 1977 Soccer Bowl, in his third and final season with the club.[34] In June 1977, the Cosmos attracted an NASL record 62,394 fans to Giants Stadium for a 3–0 victory past the Tampa Bay Rowdies with a 37-year-old Pelé scoring a hat-trick. In the first leg of the quarter-finals, they attracted a US record crowd of 77,891 for what turned into an 8–3 rout of the Fort Lauderdale Strikers at Giants Stadium. In the second leg of the semi-finals against the Rochester Lancers, the Cosmos won 4–1.[33] Pelé finished his official playing career on August 28, 1977, by leading the New York Cosmos to their second Soccer Bowl title with a 2–1 win over the Seattle Sounders at the Civic Stadium in Portland, Oregon.[35]

On October 1, 1977, Pelé closed out his career in an exhibition match between the Cosmos and Santos. The match was played in front of a sold-out crowd at Giants Stadium and was televised in the US on ABC's Wide World of Sports as well as throughout the world. Pelé's father and wife both attended the match, as well as Muhammad Ali and Bobby Moore.[19] Delivering a message to the audience before the start of the game—"Love is more important than what we can take in life"—Pelé played the first half with the Cosmos, the second with Santos. The game ended with the Cosmos winning 2–1, with Pelé scoring with a 30-yard free-kick for the Cosmos in what was the final goal of his career. During the second half, it started to rain, prompting a Brazilian newspaper to come out with the headline the following day: "Even The Sky Was Crying."[36]

International career

Pelé began playing for the Brazil national team at 16. During his international career, he won three FIFA World Cups: 1958, 1962, and 1970, the only player to do so and the youngest player to win a World Cup (17). He was nicknamed O Rei (The King) following the 1958 tournament. With 77 goals in 92 games Pelé held the record as the national team's top goalscorer for over fifty years.

Pelé's first international match was a 2–1 defeat against Argentina on July 7, 1957 at the Maracanã. In that match, he scored his first goal for Brazil aged 16 years and nine months, the youngest goalscorer for his country.[37]

1958 World Cup

Pelé arrived in Sweden for the 1958 World Cup sidelined by a knee injury, with the result that his first match was against the USSR in the third match of the first round. Once on the team he was indispensable. Against France in the semi-final, Brazil was leading 2–1 at halftime, and then Pelé scored a hat-trick, becoming the youngest player in World Cup history to do so. On June 29, 1958, Pelé became the youngest player to play in a World Cup final match at 17 years and 249 days. He scored two goals in that final as Brazil beat Sweden 5–2 in Stockholm, the capital.[38]

Pelé's first goal, where he flicked the ball over a defender before volleying into the corner of the net, was selected as one of the top ten best goals in the history of the World Cup.[39] Following Pelé's second goal, Swedish player Sigvard Parling would later comment, "After the fifth goal, even I wanted to cheer for him."[24]

He finished the tournament with six goals in four matches played, tied for second place, behind record-breaker Just Fontaine, and was named best young player of the tournament.[40] His impact was arguably greater off the field, with Barney Ronay writing, "With nothing but talent to guide him, the boy from Minas Gerais became the first black global sporting superstar, and a source of genuine uplift and inspiration."[41]

1959 South American Championship

Pelé also played in the South American Championship. In the 1959 competition he was named best player of the tournament and was the top scorer with eight goals, as Brazil came second despite being unbeaten in the tournament. He scored in five of Brazil's six games, including two goals against Chile and a hat-trick against Paraguay.[42]

1962 World Cup

When the 1962 World Cup started, Pelé was rated the best player in the world. In the first match of the 1962 World Cup in Chile, against Mexico, Pelé assisted the first goal and then scored the second one, after a run past four defenders, to go up 2–0. However, he was injured in the next game, which put him out of the rest of the tournament.[43] Brazil won the tournament but at the time, only players who appeared in the final were eligible for a medal. FIFA regulations were changed in 1978 to include the entire squad, and Pelé received his winner's medal retroactively in 2007.[44]

1966 World Cup

Pelé was the most famous footballer in the world during the 1966 World Cup in England, and Brazil fielded world champions like Garrincha, Gilmar, and Djalma Santos with the addition of other stars Jairzinho, Tostão, and Gérson, leading to high expectations for them. However, Brazil was eliminated in the first round, playing only three matches.[45] The World Cup was marked, among other things, for brutal fouls on Pelé that left him injured by the Bulgarian and Portuguese defenders.[46]

Pelé scored the first goal from a free kick against Bulgaria, becoming the first player to score in three successive FIFA World Cups, but due to his injury, a result of persistent fouling by the Bulgarians, he missed the second game against Hungary.[45] His coach stated that after the first game he felt "every team will take care of him in the same manner."[46] Brazil lost that game and Pelé, although still recovering, was brought back for the last crucial match against Portugal at Goodison Park in Liverpool by the Brazilian coach Vicente Feola. During the game, Portugal defender João Morais fouled Pelé, but was not sent off by referee George McCabe; a decision retrospectively viewed as being among the worst refereeing errors in World Cup history.[47] Brazil lost the match against the Portuguese led by Eusébio and were eliminated from the tournament as a result. After this game Pelé vowed he would never again play in the World Cup, a decision he would later change.[43]

1970 World Cup

Pelé was called to the national team in early 1969, he refused at first, but then accepted and played in six World Cup qualifying matches, scoring six goals.[48] Brazil's squad for the tournament featured major changes from the 1966 squad since players like Garrincha, Nilton Santos, Valdir Pereira, Djalma Santos, and Gilmar had already retired. However, Brazil's 1970 World Cup squad, which included Pelé, Rivelino, Jairzinho, Gérson, Carlos Alberto Torres, Tostão, and Clodoaldo, is often considered to be the greatest football team in history.[49]

The front five of Jairzinho, Pelé, Gerson, Tostão, and Rivelino together created an attacking momentum, with Pelé having a central role in Brazil's way to the final. The group stage match again England featured the goal he didn't score: In the first half of the match, Pelé nearly scored with a header that was saved by the England goalkeeper Gordon Banks. Pelé recalled he was already shouting "Goal" when he headed the ball. It was often referred to as the "save of the century."[50]

"I have scored more than a thousand goals in my life and the thing people always talk to me about is the one I didn't score." — Pele on the extraordinary save by England goalkeeper Gordon Banks in their 1970 World Cup match.[51]

Brazil played Italy in the final at the Azteca Stadium in Mexico City. Pelé scored the opening goal with a header after out jumping Italian defender Tarcisio Burgnich. Brazil's 100th World Cup goal, Pelé's leap of joy into the arms of teammate Jairzinho in celebrating the goal is regarded as one of the most iconic moments in World Cup history.[52]

The last goal of the game is often considered the greatest team goal of all time because it involved all but two of the team's outfield players. The play culminated after Pelé made a blind pass that went into Carlos Alberto's running trajectory. He came running from behind and struck the ball to score.[53] Brazil won the match 4–1, keeping the Jules Rimet Trophy indefinitely, and Pelé received the Golden Ball as the player of the tournament. Burgnich, who marked Pelé during the final, was quoted saying, "I told myself before the game, he's made of skin and bones just like everyone else – but I was wrong."[54]

Pelé's last international match was on 18 July 1971 against Yugoslavia in Rio de Janeiro. With Pelé on the field, the Brazilian team's record was 67 wins, 14 draws, and 11 losses.[48]

Style of play

A prolific goalscorer, Pelé was known for his ability to anticipate opponents in the area and finish off chances with an accurate and powerful shot with either foot.[55] Pelé was also a hard-working team player, and a complete forward, with exceptional vision and intelligence, who was recognized for his precise passing and ability to link up with teammates and provide them with assists.[56]

In his early career, he played in a variety of attacking positions. Although he usually operated inside the penalty area as a main striker or centre forward, his wide range of skills also allowed him to play in a more withdrawn role, as an inside forward or second striker, or out wide. In his later career, he took on more of a deeper playmaking role behind the strikers, often functioning as an attacking midfielder.[3] Pelé's unique playing style combined speed, creativity, and technical skill with physical power, stamina, and athleticism. His excellent technique, balance, flair, agility, and dribbling skills enabled him to beat opponents with the ball, and frequently saw him use sudden changes of direction and elaborate feints to get past players, such as his trademark move, the drible da vaca.[57] Another one of his signature moves was the paradinha, or little stop. Pelé would stop in the middle of a run-up to a penalty kick before shooting the ball; goalkeepers complained that this gave strikers an unfair advantage, however, and in the 1970s, FIFA banned this move from competitions.[3]

Despite his relatively small stature, 1.73 meters (5.7 ft), he excelled in the air, due to his heading accuracy, timing, and elevation.[55] Renowned for his bending shots, he was also an accurate free-kick taker, and penalty taker, although he often refrained from taking penalties, stating that he believed it to be a cowardly way to score.[51]

Pelé was also known to be a fair and highly influential player, who stood out for his charismatic leadership and sportsmanship on the pitch. His warm embrace of Bobby Moore following the Brazil vs England game at the 1970 World Cup is viewed as the embodiment of sportsmanship, with The New York Times stating the image "captured the respect that two great players had for each other. As they exchanged jerseys, touches, and looks, the sportsmanship between them is all in the image. No gloating, no fist-pumping from Pelé. No despair, no defeatism from Bobby Moore."[58]

After football

In 1994, Pelé was appointed a Goodwill Ambassador for the UN Children’s Fund UNICEF and as a UNESCO Champion for Sport.[59] In 1995, Brazilian President Fernando Henrique Cardoso appointed Pelé to the position of extraordinary minister for sport, a position he held until 1998. During this time he proposed legislation to reduce corruption in Brazilian football, which became known as the "Pelé law."[60]

In 1997, he received an honorary knighthood from Queen Elizabeth II at a ceremony in Buckingham Palace.[61] In 2006, Pelé made the draw for the qualification groups for the FIFA World Cup finals.[62] He appeared at the closing ceremony of the 2012 Summer Olympics in London, following the handover section to the next host city for the 2016 Summer Olympics, Rio de Janeiro.

Pelé published several autobiographies, starred in documentary films, and composed musical pieces, including Sérgio Mendes' soundtrack for the film Pelé directed by François Reichenbach in 1977.[63] He also appeared in the 1981 film Escape to Victory, about a World War II-era football match between Allied prisoners of war and a German team. Pelé starred alongside other footballers of the 1960s and 1970s, with actors Michael Caine and Sylvester Stallone.[64]

In 2003 he joined with Sun Myung Moon in establishing the Peace Cup. An invitational pre-season friendly football tournament for club teams, it was held every two years in South Korea (2003, 2005, 2007, and 2012), and Spain (2009).

The most notable area of Pelé's life since football was his ambassadorial work. In 2012, Pelé was awarded an honorary degree from the University of Edinburgh for "significant contribution to humanitarian and environmental causes, as well as his sporting achievements".[65]

In addition to his ambassadorial work, Pelé supported various charitable causes, such as Action for Brazil's Children, Gols Pela Vida, SOS Children's Villages, The Littlest Lamb, Prince's Rainforests Project and many more. In 2018, Pelé founded his charitable organization, the Pelé Foundation, which endeavors to empower impoverished and disenfranchised children from around the globe.[66]

Legacy

Pelé was known the world over as the greatest in football. He used his UNESCO Goodwill Ambassador's status to promote more than just football: "Every kid in the world who plays football wants to be Pelé," he said, "which means I have the responsibility of showing them how to be a footballer but also how to be a man."[67] Pelé was also known for connecting the phrase "The Beautiful Game" with football.[68] After a reporter asked if his fame compared to that of Jesus, Pelé joked, "There are parts of the world where Jesus Christ is not so well known."[54]

I used to go out and people said Pelé! Pelé! Pelé! Pelé! all over the world, but no one remembers Edson. Edson is the person who has the feelings, who has the family, who works hard, and Pelé is the idol. Pelé doesn't die. Pelé will never die. Pelé is going to go on for ever. But Edson is a normal person who is going to die one day, and the people forget that.[50]

Among the most successful and popular sports figures of the twentieth century, Pelé is one of the most lauded players in the history of football and has been frequently ranked the best player ever.[69] Among his contemporaries, Dutch star Johan Cruyff stated, "Pelé was the only footballer who surpassed the boundaries of logic."[24] Brazil's 1970 World Cup-winning captain Carlos Alberto Torres opined: "His great secret was improvisation. Those things he did were in one moment. He had an extraordinary perception of the game."[24] According to Tostão, his strike partner at the 1970 World Cup: "Pelé was the greatest – he was simply flawless. And off the pitch he is always smiling and upbeat. You never see him bad-tempered. He loves being Pelé."[24] His Brazilian teammate Clodoaldo commented on the adulation he witnessed: "In some countries they wanted to touch him, in some they wanted to kiss him. In others they even kissed the ground he walked on. I thought it was beautiful, just beautiful."[24]

Former Real Madrid and Hungary star Ferenc Puskás stated: "The greatest player in history was Di Stéfano. I refuse to classify Pelé as a player. He was above that."[24] Just Fontaine, French striker and the leading scorer at the 1958 World Cup said "When I saw Pelé play, it made me feel I should hang up my boots."[24] England's 1966 FIFA World Cup-winning captain Bobby Moore commented:

Pelé was the most complete player I've ever seen, he had everything. Two good feet. Magic in the air. Quick. Powerful. Could beat people with skill. Could outrun people. Only five feet and eight inches tall, yet he seemed a giant of an athlete on the pitch. Perfect balance and impossible vision. He was the greatest because he could do anything and everything on a football pitch. I remember João Saldanha the coach being asked by a Brazilian journalist who was the best goalkeeper in his squad. He said Pelé. The man could play in any position".[55]

Former Manchester United striker and member of England's 1966 FIFA World Cup-winning team Sir Bobby Charlton stated, "I sometimes feel as though football was invented for this magical player."[24]

After retiring, Pelé continued to be lauded by players, coaches, journalists and others.

US politician and political scientist Henry Kissinger stated: "Performance at a high level in any sport is to exceed the ordinary human scale. But Pelé's performance transcended that of the ordinary star by as much as the star exceeds ordinary performance."[70] The artist Andy Warhol (who painted a portrait of Pelé) also quipped, "Pelé was one of the few who contradicted my theory: instead of 15 minutes of fame, he will have 15 centuries."[24] Barney Ronay, writing for The Guardian, stated, "What is certain is that Pelé invented this game, the idea of individual global sporting superstardom, and in a way that is unrepeatable now."[41]

In 2014, the city of Santos inaugurated the Pelé museum – Museu Pelé – which displays a 2,400 piece collection of Pelé memorabilia. Approximately $22 million was invested in the construction of the museum, housed in a nineteenth-century mansion.[71]

When Pelé's death was announced, tributes were paid by current players, including Neymar, Cristiano Ronaldo, Kylian Mbappé, and Lionel Messi, other major sporting figures, celebrities, and world leaders. FIFA President, Gianni Infantino, said:

Pelé had a magnetic presence and, when you were with him, the rest of the world stopped. Today, we all mourn the loss of the physical presence of our dear Pelé, but he achieved immortality a long time ago and therefore he will be with us for eternity.[72]

Brazilian president, Jair Bolsonaro, declared a three-day period of national mourning.[73] The national flags of the 211 member associations of FIFA were flown at half-mast at FIFA headquarters in Zürich. Landmarks and stadiums lit up in honor of Pelé included the Christ the Redeemer statue and Maracanã Stadium in Rio de Janeiro, the headquarters of CONMEBOL in Paraguay, and Wembley Stadium in London.

Pelé's funeral, which involved his body being publicly displayed in an open coffin which was draped with the flags of Brazil and Santos FC, began at Vila Belmiro stadium in Santos on January 2, 2023. Thousands of fans flooded the streets to attend the first day of the funeral service.[74] The public wake would continue to January 3rd, and saw more than 230,000 people in attendance. Brazil President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva was also among those who attended the wake.[75] Brazil television channels suspended normal broadcasting to cover the funeral procession. Pelé's wife Marcia Aoki, his son Edinho, FIFA president Gianni Infantino, CONMEBOL president Alejandro Domínguez and president of the Brazilian Football Confederation Ednaldo Rodrigues were among those in attendance.[75]

Career statistics

According to the RSSSF, Pelé was one of the most successful goal-scorers in the world. He is ranked among the leading scorers in football history in both official and total matches. After his retirement in 1977 he played eight exhibition games, scoring three goals.

Club

Pelé's goalscoring record is often reported by FIFA as being 1,281 goals in 1,363 games. This figure includes goals scored by Pelé in friendly club matches, including international tours Pelé completed with Santos and the New York Cosmos, and a few games Pelé played in for the Brazilian armed forces teams during his national service in Brazil and the Selection Team of São Paulo State for the Brazilian Championship of States (Campeonato Brasileiro de Seleções Estaduais).[76] In 2000, IFFHS declared Pelé as the "World's Best and successful Top Division Goal Scorer of all time" with 541 goals in 560 games and honored him with a trophy.[77]

International

With 77 goals in 92 official appearances, Pelé is the joint-top scorer of the Brazil national football team (tied with Neymar).[76] He scored twelve goals and is credited with ten assists in fourteen World Cup appearances, including four goals and seven assists in 1970.[78] Pelé shares with Uwe Seeler, Miroslav Klose, Lionel Messi, and Cristiano Ronaldo, the achievement of being the only players to have scored in four separate World Cup tournaments.[79]

Notes

- ↑ According to Pelé, his birth certificate listed it incorrectly as October 21, 1940.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Pele and Robert L. Fish, Pele, My Life and the Beautiful Game (Doubleday, 1977, ISBN 978-0385121859).

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Pelé, Pelé: The Autobiography (Simon & Schuster UK, 2006, ISBN 978-0743275835).

- ↑ From Edson to Pelé: my changing identity The Guardian (May 12, 2006). Retrieved February 15, 2024.

- ↑ Denise Winterman, Taking the Pelé BBC News (January 4, 2006). Retrieved February 15, 2024.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Pele Speaks of Benefits of Futebol de Salão International Confederation of Futebol de Salão, May 24, 2006. Retrieved June 14, 2024.

- ↑ Pele's daughter dies of cancer at 42 ESPN (October 17, 2006). Retrieved June 17, 2024.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Jason Pham, Pelé Had 7 Kids With 4 Women Before His Death—See All His Children & Where They Are Now Stylecaster (December 31, 2022). Retrieved June 17, 2024.

- ↑ Marcelo Gomes and Rafael Valente, Filha de Pelé, Flávia Kurtz revela última conversa, diz que Rei temia a morte e anuncia novidade importante ESPN (May 12, 2023). Retrieved June 17, 2024.

- ↑ Football legend Pele marries 'definitive love' The Belfast Telegraph (July 10, 2016). Retrieved June 17, 2024.

- ↑ Pele recovering in hospital after collapsing with exhaustion The Telegraph (January 19, 2018). Retrieved June 17, 2024.

- ↑ Pele: Brazil legend reluctant to leave his home, says son Edinho Sky Sports (February 11, 2020). Retrieved June 17, 2024.

- ↑ Pelé: Brazil legend remains in intensive care as he recovers from surgery to remove tumour Sky Sports (September 11, 2021). Retrieved June 17, 2024.

- ↑ Pele released from hospital to begin chemotherapy Deutsche Welle (DW) (September 30, 2021). Retrieved June 17, 2024.

- ↑ Morre o Rei Pelé aos 82 anos ge (December 29, 2022). Retrieved June 17, 2024.

- ↑ Pele: Brazil great's cancer has advanced, says hospital BBC Sport (December 21, 2022). Retrieved June 17, 2024.

- ↑ Michael Drummond, Brazilian football icon Pele has died at the age of 82 Sky News (December 29, 2022). Retrieved June 17, 2024.

- ↑ Camilo Rocha, George Ramsay, Tara John, Flora Charner, and Rodrigo Pedroso, Brazilian soccer legend Pelé dies at 82 CNN (December 29, 2022). Retrieved June 22, 2024.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Lew Freedman, Pelé: A Biography (Greenwood, 2014, ISBN 978-1440829802).

- ↑ Louis Massarela, Exclusive interview: Pele on his Santos years FourFourTwo (September 7, 2016). Retrieved June 18, 2024.

- ↑ Joe Marcus, The World of Pelé (Mason Charter Publishing, 1976, ISBN 0884053660).

- ↑ Cesar Chelala, Pele, Maradona and Messi: soccer's holy trinity The Japan Times (April 11, 2014). Retrieved June 18, 2024.

- ↑ Santos revive spirit of Pele BBC Sport (February 16, 2003). Retrieved June 18, 2024.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 24.3 24.4 24.5 24.6 24.7 24.8 24.9 "What they said about Pele" FIFA (October 23, 2010). Retrieved June 18, 2024.

- ↑ José Luis Pierrend, John Beuker, Pablo Ciullini and Osvaldo Gorgazzi, Copa Libertadores de América 1962 RSSSF, November 29, 2012. Retrieved June 18, 2024.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 "Intercontinental Cups 1962 and 1963" FIFA, January 15, 2015. Retrieved June 18, 2024.

- ↑ Alex Bellos, Futebol: The Brazilian Way of Life (Bloomsbury, 2014, ISBN 1620402440).

- ↑ Juan Pablo Andrés, Frank Ballesteros, and Roberto Di Maggio, Copa Libertadores – Topscorers RSSSF, December 14, 2023. Retrieved June 18, 2024.

- ↑ Why Pele's 1000th goal still matters, 50 years on Sportstar (November 19, 2019). Retrieved June 18, 2024.

- ↑ Jerrad Peters, Pele: Recalling the Moments That Defined His Career Bleacher Report (May 8, 2013). Retrieved June 17, 2024.

- ↑ R.W. Apple Jr., Pele to Play Soccer Here for $7‐Million The New York Times (June 4, 1975). Retrieved June 17, 2024.

- ↑ Michael Lewis, 40 years on: how New York Cosmos lured Pelé to a football wasteland The Guardian (June 2, 2015). Retrieved June 19, 2024.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 Michael Lewis, How Pelé lit up soccer in America and left a legacy fit for a king The Guardian (September 30, 2017). Retrieved June 19, 2024.

- ↑ Tom Dunmore, Historical Dictionary of Soccer (Scarecrow Press, 2011, ISBN 978-0810871885), 198.

- ↑ Earl Gustkey, Pele's Contributions Gave Soccer a Foothold Los Angeles Times (August 28, 1999). Retrieved June 20, 2024.

- ↑ Tony Kornheiser, 'Love! Love! Love!' Cries Pele to 75,646 in Farewell The New York Times (October 2, 1977). Retrieved June 20, 2024.

- ↑ Bob Williams, Top 10: Young sporting champions The Telegraph (October 29, 2008). Retrieved June 20, 2024.

- ↑ Will Hawkes, Flashback No 6. Sweden 1958: Pele's genius propels Brazil to first title The Independent (May 26, 2010). Retrieved June 20, 2024.

- ↑ Diego Maradona goal voted the FIFA World Cup™ Goal of the Century FIFA, May 30, 2002. Retrieved June 20, 2024.

- ↑ 1958 FIFA World Cup Sweden – Awards FIFA. Retrieved June 20, 2024.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 Barney Ronay, Pelé's revolutionary status must survive numbers game against Lionel Messi The Guardian (February 3, 2021). Retrieved June 20, 2024.

- ↑ Martin Tabeira, Southamerican Championship 1959 (1st Tournament) RSSSF. Retrieved June 20, 2024.

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 Hall of Fame: PELE International Football Hall of Fame (IFHOF). Retrieved June 20, 2024.

- ↑ Pele and Greaves to get World Cup winners medals The Guardian (November 25, 2007). Retrieved June 20, 2024.

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 1966 FIFA World Cup England: Group 3 FIFA. Retrieved June 20, 2024.

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 Simon Burnton, Why not everyone remembers the 1966 World Cup as fondly as England The Guardian (July 24, 2016). Retrieved June 20, 2024.

- ↑ Nick Collins, World Cup final: 10 top World Cup refereeing errors The Telegraph (July 9, 2010). Retrieved June 20, 2024.

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 Roberto Mamrud, Edson Arantes do Nascimento "Pelé" – Goals in International matches RSSSF, May 23, 2004. Retrieved June 21, 2024.

- ↑ Jack Bell, 1970 Brazilian Soccer Team Voted Best Ever The New York Times (July 11, 2007). Retrieved June 21, 2024.

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 Simon Hattenstone, And God created Pelé The Guardian (June 29, 2003). Retrieved June 21, 2024.

- ↑ 51.0 51.1 Emmanuel Egobiambu, 'Born To Play Football': Top Quotes About Brazil Legend Pele Channels Television (December 29, 2022). Retrieved June 21, 2024.

- ↑ Coca-Cola Memorable Celebrations 1: Pele's Iconic Leap Of Joy After Scoring Brazil's Century Goal Goal, September 19, 2023. Retrieved June 21, 2024.

- ↑ Andrew Benson, The perfect goal BBC Sport (June 2, 2006). Retrieved June 21, 2024.

- ↑ 54.0 54.1 Gentry Kirby, Pele, King of Futbol ESPN. Retrieved June 21, 2024.

- ↑ 55.0 55.1 55.2 Frank Malley, Pele, the perfect player The Independent (December 23, 1999). Retrieved June 21, 2024.

- ↑ David Miller, Maradona's genius cannot eclipse Brazilian master The Telegraph (December 12, 2000). Retrieved June 21, 2024.

- ↑ Rob Hughes, The Greatest? For Century, Pele Eclipses Muhammad Ali The New York Times (December 29, 1999). Retrieved June 21, 2024.

- ↑ Rob Hughes, A Shot That Captured the Bigger Meaning in Sports The New York Times (September 15, 2010). Retrieved June 21, 2024.

- ↑ UNESCO ‘deeply saddened’ over death of football legend, Pelé United Nations, December 29, 2022. Retrieved June 22, 2024.

- ↑ Pele Law on sports introduced in Brazil BBC News (March 25, 1998). Retrieved June 22, 2024.

- ↑ Education: Sir Pele lends his support The Independent (December 4, 1997). Retrieved June 22, 2024.

- ↑ Dave Blevins, The Sports Hall of Fame Encyclopedia: Baseball, Basketball, Football, Hockey, Soccer (Scarecrow Press, 2011, ISBN 978-0810861305).

- ↑ Pelé (1977) IMDb. Retrieved June 22, 2024.

- ↑ Victory (1981) IMDb. Retrieved June 22, 2024.

- ↑ Pelé receives honorary degree University of Edinburgh Annual Review 2012/13. Retrieved June 22, 2024.

- ↑ Pelé Foundation. Retrieved June 22, 2024.

- ↑ Ritabrata Banerjee, 70 facts about Brazil legend Pele Goal (March 31, 2023). Retrieved June 22, 2024.

- ↑ Duncan White, The World Cup will show why football is still a beautiful game The Telegraph (June 12, 2014). Retrieved June 22, 2024.

- ↑ Pele tops World Cup legends poll BBC News (June 12, 2006). Retrieved June 22, 2024.

- ↑ Henry Kissinger, PELE: The Phenomenon TIME (June 14, 1999). Retrieved June 22, 2024.

- ↑ Brazil inaugurates Pele Museum ESPN, June 16, 2014. Retrieved June 22, 2024.

- ↑ Gianni Infantino, Immortal - forever with us FIFA, December 29, 2022. Retrieved June 22, 2024.

- ↑ Brazil starts three days of mourning as country lights up in memory of Pelé ITV News, December 30, 2022. Retrieved June 22, 2024.

- ↑ Andrew Downie, 'I had to say goodbye': thousands pay their respects to Pelé in Brazil The Guardian (January 2, 2022). Retrieved June 22, 2024.

- ↑ 75.0 75.1 Tom Phillips and Ana Ionova, Brazil president joins mourners paying tribute to Pelé before funeral The Guardian (January 3, 2022). Retrieved June 22, 2024.

- ↑ 76.0 76.1 Anirudh Menon, Pele's incredible numbers: hundreds of goals and 3 World Cups ESPN (December 29, 2022). Retrieved June 21, 2024.

- ↑ IFFHS News and Statistics of the Week 51 IFFHS News (December 19, 2020). Retrieved June 21, 2024.

- ↑ Pele helps Brazil to World Cup title History.com. Retrieved June 21, 2024.

- ↑ Robert Summerscales, Lionel Messi Equals World Cup Record Set By Cristiano Ronaldo And Pele Sports Illustrated Fan Nation (November 22, 2022). Retrieved June 21, 2024.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Bellos, Alex. Futebol: The Brazilian Way of Life. Bloomsbury, 2014. ISBN 1620402440

- Blevins, Dave. The Sports Hall of Fame Encyclopedia: Baseball, Basketball, Football, Hockey, Soccer. Scarecrow Press, 2011. ISBN 978-0810861305

- Dunmore, Tom. Historical Dictionary of Soccer. Scarecrow Press, 2011. ISBN 978-0810871885

- Freedman, Lew. Pelé: A Biography. Greenwood, 2014. ISBN 978-1440829802

- Marcus, Joe. The World of Pelé. Mason Charter Publishing, 1976. ISBN 0884053660

- Pelé. Pelé: The Autobiography. Simon & Schuster UK, 2006. ISBN 978-0743275835

- Pele, and Fish, Robert L. Pele, My Life and the Beautiful Game. Doubleday, 1977. ISBN 978-0385121859

External links

All links retrieved June 21, 2024.

- Pelé: A Legend Looks Back – slideshow by Life magazine

- Pelé Santos official website

- In Memoriam: Pelé Universal Peace Federation

- Pelé IMDb

- Pele was the benchmark against whom all other great players are measured by Gabriele Marcotti, ESPN, December 29, 2022.

- Pelé Foundation

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.