Rakugo

Rakugo (落語 literally, "fallen words") is a form of Japanese verbal entertainment. A lone storyteller (rakugoka) sits on the stage, called the kōza (高座), and using only a paper fan and a hand towel as props, recounts, without rising from his seat, a long and complicated comical story. The story is narrated as a conversation among two or more characters. The performer switches from one character to another, changing his voice, facial expression, mannerisms, and accent to fit the person who is speaking. The monologue typically lasts for 30 minutes and ends with a surprise punch line, a narrative stunt known as ochi (fall) or sage (lowering).

Rakugo originated from Buddhist sermons. The priests used dramatic stories to illustrate the spiritual principles of Buddhism such as the transiency of life, ephemeral reality of secular values, and others. Early rakugo performers parodied those stories to relieve people from the painful reality of life by helping them to laugh at themselves.

Rakugo became a form of popular entertainment during the the Edo period (1603–1867), when it was often performed in vaudeville-type urban theaters called yose. The presentation and style of rakugo performance has changed very little since the late eighteenth century, but the storyteller’s freedom to improvise and incorporate modern slang and references to recent events has kept it popular. New stories are constantly being created and added to the traditional repertoire of over 300 classic stories. Rakugo performances, or comic sketches derived from them, often appear on television, and modern rakugokas (Rakugo performers) also perform in other capacities as actors, comedians, and hosts of television shows.

Lexical background

Rakugo was originally known as karukuchi. The oldest appearance of the kanji which refers specifically to this type of performance dates to 1787, but at the time the characters themselves were read as otoshibanashi (falling discourse).

The expression rakugo was first used in the middle of the Meiji period (1867–1912) and came into common usage during the Shōwa period (1926–1989).

Performance

The performance of rakugo follows stylized conventions established almost 300 years ago. A band plays music to announce the entrance of the rakugoka. The storyteller, wearing a traditional Japanese kimono, sometimes supplemented with a pair of long, wide pants (hakama) and a formal jacket (haori), enters, bows to the audience, and seats himself on a cushion. The stage, called the kōza (高座), is usually bare, but may be furnished with a small table. The rakugoka greets the audience, then launches into a long and complicated comical story. Performances are generally 30 minutes in length, although the teller must be agile enough to lengthen or shorten the piece as needed.

The performer is normally equipped with two props, a paper fan (sensu) and a hand towel (tenugui), with which he illustrates his monologue. The fan can be used to represent long objects, such as chopsticks, scissors, cigarettes, pipe, or pen. The towel is used for flat items such as a book, bills, or an actual towel.

The story is always in the form of a conversation between two or more characters. The performer switches fluidly and seamlessly from one character to another, changing his voice, facial expression, mannerisms, and accent to fit the character who is speaking. A slight turn of the head and a change in pitch is used to indicate a switch from one character to another. Most characters have strong stereotypical personalities, representing universal human qualities, so that the audience can easily detect the change from one character to another. Favorite character stereotypes are:

- Stupid, hasty, rash, forgetful, clumsy

- Smart, reliable, short-tempered

- Pretentious, vain

- Cunning, tricky, quick-witted

- Authority figure, man of power

- Canny, stingy, miserly, mean

- Alluring, provocative

- Liar, braggart, untruthful

- Non-human characters, such as animals or ghosts

The monologue always ends with a punch line, a narrative stunt known as ochi (fall) or sage (lowering), consisting of a sudden interruption of the wordplay flow. Twelve kinds of ochi are codified and recognized, with more complex variations having evolved, through time, from the more basic forms.[1]

The rakugoka captures his audience by creating dramatic tension with drawn-out pantomime and exquisite facial expressions, then releasing the tension with a funny comment, a pun, or an unexpected twist to the story. The comic situations portray fundamental human experiences, such as a man’s desire to associate with a woman; an argument between a married couple; someone’s reaction to the smile of a baby; a merchant’s greed; the gossip of a nosy neighbor.[2]

Early rakugo has developed into various styles, including shibaibanashi (theatre discourses), ongyokubanashi (musical discourses), kaidanbanashi (kaidan; ghost discourses), and ninjōbanashi (sentimental discourses). In many of these forms the ochi, an essential element of the original rakugo, is absent.

Noriko Watanabe, an assistant professor in the Department of Modern Languages and Comparative Literature at Baruch College, describes rakugo as resembling "a sitcom with one person playing all the parts."[3]

History

Humorous Japanese narratives can be found in the story collection Uji Shūi Monogatari (1213–1218). Gradually the humorous stories came to be narrated as monologues. According to Noriko Watanabe, the earliest rakugokas (comic storytellers) parodied the allegorical stories used in Buddhist sermons to educate common people about spiritual principles.[4] At first, they entertained passersby in the streets, and later they performed for feudal lords at celebrations and gatherings.

During the Edo period (1603–1867), a large and wealthy urban merchant class (chonin) emerged in Japan, creating a demand for popular entertainment among the lower classes. Rakugo was showcased in vaudeville-type urban theatres (called yose), along with other entertainments like juggling and magic. Many groups of performers were formed, and collections of texts were finally printed. During the seventeenth century, the actors were known as hanashika (“storyteller”), corresponding to the modern term, rakugoka (“person of the falling word”).

The forerunner of modern rakugo was kobanashi: Short comical vignettes ending with an ochi, popular between the seventeenth and the nineteenth century. These were enacted in small public venues, or in the streets, and printed and sold as pamphlets. The origin of kobanashi is to be found in the Kinō wa kyō no monogatari (Yesterday Stories Told Today, c. 1620), the work of an unknown author collecting approximately 230 stories describing the middle class.

The presentation and style of rakugo performance has changed very little since the late 18th century[5]. Many of the stories are drawn from the urban life of the Edo period.

Though the performance of rakugo is highly stylized, improvisation and the addition of modern content have kept it a popular form of entertainment. Storytellers often incorporate references to recent events and current social issues, and change the phrasing to include modern slang, combining the traditional styles with modern storytelling. New stories are constantly being created and added to the repertoire of hundreds of classic stories. Rakugo is a versatile genre that can be performed successfully in many situations. It has never been considered a highly refined art form, and until recently, received no official recognition from the Japanese government as a cultural asset. Rakugo performances, or comic sketches derived from them, often appear on television, and modern rakugokas also perform in other capacities as actors, comedians, and television show hosts.

Training of a rakugoka

Pupils who wish to become rakugo performers are called deshi. The traditional way of studying rakugo is through an apprenticeship to a professional rakugoka. The training is all verbal; the rakugoka tells a story and the student attempts to imitate him, until he has mastered the story well enough to add his own embellishments. Recently, audio and video recordings have also been used for training, but written text is not employed. Deshi learn how to create characters, use various linguistic devices, and extract the essence of a story. They master the use of the two rakugo props, the fan and the towel, and may also take lessons in dancing or playing a musical instrument.

During his apprenticeship, a student may live with the master and carry out responsibilities such as cleaning, cooking or driving. The master is responsible for the student’s financial needs, and provides opportunities for him to perform on stage. After training for two to four years, with the master’s permission, the deshi becomes a rakugoka and begins build a following and expand his repertoire.

Rakugo stories

Approximately 300 popular stories are still performed as classic rakugo, in addition to many new stories created by current rakugo artists following the traditional style and structure. Each story is made of three parts: The makura, or prelude; the hondai (hanashi), or main story; and the ochi, the closing punch line. The punch line defines the genre. The word makura means “pillow,” and signifies the placing of the head on a pillow prior to entering into a dreamlike state. Throughout the story and the punch line (sage) which occurs at the end of the story, the rakugoka inserts kusuguri or "jabs of laughter," through extreme postures, wordplay, exaggeration of the character’s way of speaking, or twists in the story line. The hanashi, or main story, is usually humorous, but sometimes it can be serious or miserable, with humorous moments.

Important rakugoka

Over the centuries, many artists have contributed to the development of rakugo. Some also composed original works. Among the more famous rakugoka of the Tokugawa Era were performers like Anrakuan Sakuden (1554–1642), the author of the Seisuishō (Laughter to Chase Away Sleep, 1628), a collection of more than 1,000 stories. Shikano Buzaemon (1649–1699), who lived in Edo-age Tokyo, wrote Shikano Buzaemon kudenbanashi (Oral Instruction Discourses of Shikano Buzaemon) and the Shika no makifude (The Deer's Brush, 1686), a work containing 39 stories, eleven of which are about the kabuki milieu. Tatekawa Enba (1743–1822) was author of the Rakugo rokugi (The Six Meanings of Rakugo).

The works of Tsuyu no Gorobei (Kyōto, 1643–1703), are included in the Karakuchi tsuyu ga hanashi (One-liners: Morning Dew Stories, date of composition unknown), containing many word games, episodes from the lives of famous literary authors, and plays on the different dialects from the Kantō Plain, Ōsaka, and Kyōto.

Of a similar structure is the Karakuchi gozen otoko (One-liners: An Important Storyteller, date of publication unknown) in which are collected the stories of Yonezawa Hikohachi, who lived in Ōsaka towards the end of the seventeenth century. An example from Yonezawa Hikohachi's collection:

A man faints in a bathing tub. In the great confusion following a doctor arrives who takes his pulse and calmly gives the instructions: "Pull the plug and let the water out." Once the water has flown completely out of the tub he says: "Fine. Now put a lid on it and carry the guy to the cemetery." For the poor man is already dead. (The joke becomes clearer when one notes that a Japanese traditional bathing tub is shaped like a coffin.)

Current rakugokas

Current rakugo artists include Tatekawa Danshi, Tachibanaya Enzou, Katsura Sanshi, Tachibanaya Takezou, Tatekawa Shinosuke and Shōzō Hayashiya (9th). Many popular Japanese comedians originally trained as rakugo apprentices, even adopting stage names given them by their masters. Some examples include Sanma Akashiya, Tsurube Shōfukutei, and Shōhei Shōfukutei.[6] Another famous rakugo performer, Shijaku Katsura, became known outside Japan for his performances of rakugo in English.

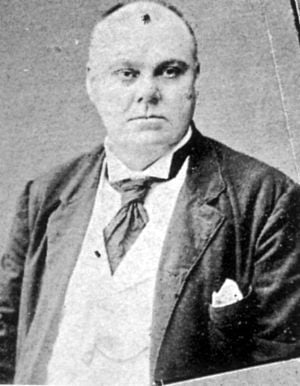

Traditionally, rakugo was performed only by males, but today there are a number of female rakugo artists, and also non-Japanese rakugoka. The first foreign rakugoka was Henry James Black (1858-1923), the son of J.R. Black, a singer and publisher of several newspapers in Japan, who performed under the name Kairakutei Black (快楽亭ブラック, Kairakutei Burakku).[7]

Jugemu

The folktale of Jugemu(寿限無), one of the most famous rakugo in Japan, has a simple story line, with the funniest part being repetition of the ridiculously long name. It is often used to train rakugo performers.

A couple could not think of a suitable name for their newborn baby boy, so the father went to the temple and asked the chief priest to think of an auspicious name. The priest suggested several names, beginning with Jugemu. The father could not decide which name he preferred, and therefore gave the baby all of the names. One day, Jugemu falls into a lake and his parents barely arrive in time to save him because everyone has trouble reciting his name.

Jugemu's full name is as follows:

- Jugemu-jugemu

- Gokōnosurikire

- Kaijarisuigyo-no Suigyōmatsu

- Unraimatsu Fūraimatsu

- Kūnerutokoroni-sumutokoro

- Yaburakōjino-burakōji

- Paipopaipo-paiponoshūringan

- Shūringanno-gūrindai :Gūrindaino-ponpokopīno-ponpokonāno

- Chōkyūmeino-chōsuke

- 寿限無寿限無

- 五劫の擦り切れ

- 海砂利水魚の 水行末

- 雲来末 風来末

- 食う寝る処に住む処

- やぶら小路のぶら小路

- パイポパイポ パイポのシューリンガン

- シューリンガンのグーリンダイ

- グーリンダイのポンポコピーのポンポコナーの

- 長久命の長助

The recitation from memory of these names is a feature of the NHK children's TV program, Nihongo de Asobou (Let's Play with Japanese Language).

See also

- Comedy

- Monologue

Notes

- ↑ Tim Ryan, Rakugo: universal laughter, Star-Bulletin. Retrieved July 12, 2008.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Baruch College, Rakugo related interview. Retrieved July 12, 2008.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Kimie Oshima. Rakugo: Japanese Sit-Down Comedy, Humor & Health Journal 12(3). Retrieved July 12, 2008

- ↑ Kimie Oshima, Rakugo Performers. Retrieved July 12, 2008

- ↑ Heinz, Morioka, and Sasaki Miyoko, The Bue-Eyed Storyteller: Henry Black and His Rakugo Career.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Brau, Lorie. 2008. Rakugo: Performing Comedy and Cultural Heritage in Contemporary Tokyo. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books. ISBN 9780739122457.

- Katsura, Shijaku. 1980. English Rakugo Script. Osaka: Beicho Office.

- McCarthy, Ralph F., and Yū Takita. 2000. Rakugo! Comic Stories From Old Japan. Kodansha Eigo Bunko, 162. Tōkyō: Kōdansha Intānashonaru Kabushiki Kaisha. ISBN 9784770024268.

- Morioka, Heinz, and Miyoko Sasaki. 1990. Rakugo, the Popular Narrative Art of Japan. Cambridge, Mass: Council on East Asian Studies, Harvard University. ISBN 9780674747258.

- Sweeney, Amin. 1979. Rakugo: Professional Japanese Storytelling. Nagoya: Nanzan University.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.