Rehoboam

Rehoboam (Hebrew: רחבעם, Rehav'am) was a king in ancient Jerusalem, succeeding his father Solomon and his grandfather David. He was the third king of the House of David and, after losing control of the northern tribes shortly after his coronation, became the first king of the later Kingdom of Judah. His name, ironically, means “he who enlarges the people.” His mother was Naamah the Ammonitess.

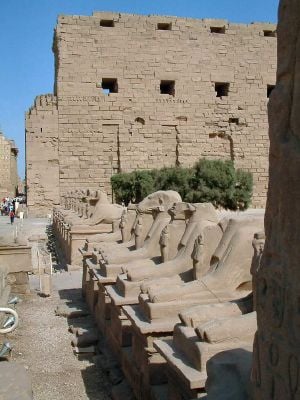

Rehoboam's reign has been dated to roughly the last quarter of tenth century B.C.E. William F. Albright dates his reign from 922-915 B.C.E.,[1] while Edwin R. Thiele puts it at 931-913 B.C.E.[2] The Bible is the main historical source for his reign. His story is told in the 1 Kings and 2 Chronicles. An inscription at Karnak in Egypt confirms part of biblical account of Rehoboam's reign.

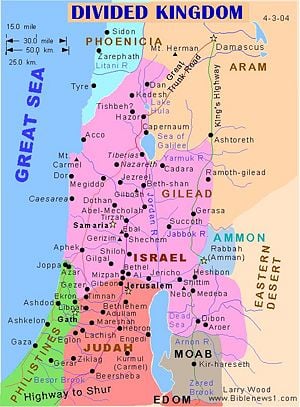

When Rehoboam refused to lighten Solomon's policy of heavy taxation and forced labor, the northern tribes seceded from his kingdom, proclaiming Jeroboam I as their king. Only the southern tribes of Judah and Benjamin remained under Rehoboam in what became known as the Kingdom of Judah. Although Rehoboam fortified several Judean towns against attack, the Egyptian king Shishak successfully invaded the country and pillaged Jerusalem in the fifth year of Rehoboam's rule. Judah then became a tributary to Egypt. Warfare against northern Kingdom of Israel also continued throughout Rehoboam's reign.

He was succeeded by his son Abijah, a grandson of David's rebellious son Absalom. In Christian tradition, Rehoboam is one of the ancestors of Jesus Christ.

The kingdom divided

Background

Rehoboam ascended the throne at the age of 41, and he reportedly reigned for 17 years. Although the biblical account holds Solomon's toleration of the religions of his foreign wives responsible for the kingdom's division in Rehoboam's time, the immediate cause of the north's rebellion was Rehoboam's labor and taxation policies. Under his father, the people were taxed heavily to pay for the Solomon's building projects, and forced labor was also mandated. Moreover, Jeroboam I, a rising young leader encouraged by the prophet Ahijah to seize the kingship of the northern tribes, had recently returned from exile in Egypt. Solomon had also accumulated several prominent enemies during his later reign: Hadad, the Egyptian-backed heir to the Edomite throne and Rezon, the son of an Aramean army captain, now the de facto ruler of Damascus.

A fateful decision

In an apparent gesture of good will to the northern tribes, Rehoboam traveled to Shechem to be crowned, rather than holding his coronation ceremony in the Judean capital of Jerusalem (1 Kings 12:1). At Shechem, he was confronted by a large delegation, "the whole assembly of Israel," with the complaint:

- Your father put a heavy yoke on us, but now lighten the harsh labor and the heavy yoke he put on us, and we will serve you. (1 Kings 12:4)

Rehoboam asked for three days to consider the issue. He first consulted the elders who had advised Solomon, and these men counseled him: "If today you will be a servant to these people and... give them a favorable answer, they will always be your servants." (12:7)

Rehoboam, however, preferred the advice of younger men, who exhorted him to demonstrate his authority by refusing to compromise. Rehoboam thus declared to the Israelites: "My father also chastised you with whips, but I will chastise you with scorpions" (1 Kings 12:14).

The north rebels

The northerners then retracted their recognition of House of David and declared independence. The Bible preserves their political slogan:

- What share do we have in David,

- what part in Jesse's son?

- To your tents, O Israel!

- Look after your own house, O David!"

Testing the Israelites' determination, Rehoboam dispatched Adoram, his minister of forced labor, to conscript Israelite men. Adoram, however, was stoned to death, and Rehoboam himself fled in haste to Jerusalem.

Jeroboam I was appointed king of the northern tribes, and their breakaway state became known as the Kingdom of Israel. Rehoboam returned to Jerusalem as king over what later became know as the Kingdom of Judah, consisting of only the areas allotted to the tribes of Judah and Benjamin.

War with Egypt

Rehoboam organized a sizable army to suppress the rebellion. Its size is given as 180,000 men by 1 Kings and by 2 Chronicles. However a prophet named Shemaiah proclaimed God's words as: "Do not go up to fight against your brothers, the Israelites." Rehoboam immediately abandoned his plans for a full scale invasion. However, he skirmished against the forces of Jeroboam I throughout the remainder of his reign.

In the fifth year of Rehoboam's reign, Pharaoh Shishak and his allies invaded Judah. The biblical narrative indicates widespread defeats for the Judahites. Jerusalem, too, was taken, and both the Temple and the royal palace were looted (2 Chronicles 11:5-12).

A remarkable memorial of this invasion has been discovered at Karnak, in Upper Egypt. An inscription of Pharaoh Sheshonq I on a temple there show the god Amun holding in his hand a train of prisoners and other figures, with the names of several captured towns of Judah, the towns which the biblical narrative identifies as having been fortified by Rehoboam.[3]

Religious Dimension

The biblical authors view Rehoboam's fate in presiding over the division of his as having been determined by his father Solomon's sin in tolerating idolatry. God reportedly told Solomon:

- Since this is your attitude and you have not kept my covenant and my decrees, which I commanded you, I will most certainly tear the kingdom away from you and give it to one of your subordinates. Nevertheless, for the sake of David your father, I will not do it during your lifetime. I will tear it out of the hand of your son. (1 Kings 11:11-12)

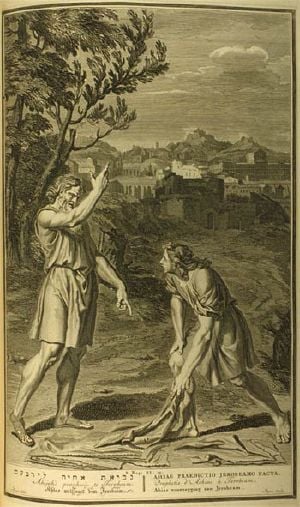

Even Jeroboam I's rebellion is foreordained by God. Having proved his merit to Solomon, Jeroboam was placed in charge of labor gangs pressed into service from the tribe of Joseph (Ephraim). Just outside of Jerusalem, Ahijah, a prophet from Shiloh, met Jeroboam and predicted that God would give him the rulership of ten Israelite tribes, leaving only one tribe to Solomon and his descendants (1 Kings 11:31). Apparently Solomon heard of the prophecy, for he tried to kill Jeroboam, who sought exile in Egypt until Solomon's death.[4]

The issues of labor and taxation are by no means dismissed as irrelevant in the biblical narrative. Indeed, Jeroboam's role as a labor leader seems to be what qualifies him for rule, along with Ahijah's blessing.

Another key element in the religious dimension of the drama is Jerusalem and its Temple. Ahijah had declared: "I will give one tribe to (Solomon's) son so that David my servant may always have a lamp before me in Jerusalem, the city where I chose to put my Name" (1 Kings 11:36).[5] The incident serves to explain how it came to pass that Jerusalem remained the authorized religious center even while God endorsed Jeroboam's rebellion.

After the division of the kingdom, Jeroboam established a rival religious center at the ancient high place of Bethel and a second center farther north at Dan. These sites became the object of scorn by later prophets and by the biblical authors.[6]

After Jeroboam's rebellion, Levite priests loyal to the Temple of Jerusalem, formerly scattered among the 12 tribes, moved in significant numbers to the capital. Jeroboam, whether out of lack of trust in the Levites or because there were now insufficient numbers of them left in the north, began appointing non-Levite priests to attend his official altars.

Meanwhile, Rehoboam himself was not living up to the biblical standard of a true "son of David" in Jerusalem:

Judah did evil in the eyes of the Lord. By the sins they committed they stirred up his jealous anger more than their fathers had done. They also set up for themselves high places, sacred stones and Asherah poles on every high hill and under every spreading tree. There were even male shrine prostitutes in the land; the people engaged in all the detestable practices of the nations the Lord had driven out before the Israelites.

Scholars debate whether there was ever a golden Davidic age in which the Yahwistic religion was practiced throughout Israel and Judah. Modern Bible scholars generally hold the view that Judah and Israel were both religiously pluralistic, and that the biblical ideal a unified religious tradition in David's time is more legendary than historical. Nevertheless, the biblical view is that Rehoboam's failure to uphold the Yahweh-only ideal is precisely what led to Egypt's successful raids on Rehoboam's cities. Chronicles reports the words of the prophet Shemaiah:

Shemaiah came to Rehoboam and to the leaders of Judah who had assembled in Jerusalem for fear of Shishak, and he said to them, "This is what the Lord says, "You have abandoned me; therefore, I now abandon you to Shishak." (2 Chron. 12:5)

The writer of Chronicles concludes his evaluation of Rehoboam in this way:

Because Rehoboam humbled himself, the Lord's anger turned from him, and he was not totally destroyed. Indeed, there was some good in Judah. King Rehoboam established himself firmly in Jerusalem and continued as king. (2 Chron. 12:12-13)

Succession

Rehoboam reportedly had 18 wives and 60 concubines. These bore him 60 daughters and 28 sons, most of the sons being appointed to important posts across the country. His primary wife was Mahalath, who was, like Rehoboam himself, a descendant of King David. She bore him three sons: Jeush, Shemariah and Zaham. Another important wife was Maacah, another descendant of David, being the daughter of the infamous Absalom. She bore him Abijah, Attai, Ziza and Shelomith. Chronicles 11:21 states, "Rehoboam loved Maacah daughter of Absalom more than any of his other wives and concubines." Rehoboam was succeeded by his son Abijah, a son of Maacah.

Although he cannot be seen as a successful king, Rehoboam's dynasty was a long-lived one. It lasted in an unbroken line of his descendants as kings of Judah (with a six-year exception for Athaliah, Judah's one reigning queen) until the time of the Babylonian exile in the sixth century B.C.E. For this accomplishment, however, the Bible gives credit to his grandfather David.

In New Testament, Rehoboam is listed as one of the ancestors of Jesus Christ in the genealogy of Matthew 1.

| Preceded by: Solomon |

King of Judah Albright: 922 B.C.E. – 915 B.C.E. Thiele: c.931 B.C.E. – 913 B.C.E. Galil: c.931 B.C.E. – 914 B.C.E. |

Succeeded by: Abijam |

Notes

- ↑ William F. Albright, The Archaeology of Palestine (Peter Smith Pub Inc, 1985, ISBN 0844600032).

- ↑ Edwin R. Thiele, The Mysterious Numbers of the Hebrew Kings (Kregel Academic & Professional, 1994, ISBN 082543825X).

- ↑ Jess Lee, Exploring Karnak's Great Temple of Amun, Luxor Planet Ware (May 20, 2021). Retrieved June 23, 2023.

- ↑ Jeroboam's period of exile in Egypt may also be related to Shishak's apparent later confidence that Israel would not come to Judah's aid when Egypt attacked the southern kingdom.

- ↑ Critical scholars suspect the prophecy is a later addition by editors of the Deuteronomistic school in support of their policy of centralizing worship of Yahweh in Jerusalem only.

- ↑ The ostensible reason for their disapproval was Jeroboam's erection of a golden bull-calf statue at these sites. Scholars suspect another motive was the fact that northern pilgrims would no longer bring their tithes and sacrificial offerings to Jerusalem since they could more easily stop at Bethel or Dan. Whatever the reason, Jerusalem emerged as the only authorized place of worship in either kingdom, in the biblical view.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Albright, William F. The Archaeology of Palestine. Peter Smith Pub Inc; 2nd edition, 1985. ISBN 0844600032

- Bright, John. A History of Israel. Westminster John Knox Press; 4th edition, 2000. ISBN 0664220681

- Finkelstein, Israel. David and Solomon: In Search of the Bible's Sacred Kings and the Roots of the Western Tradition. Free Press, 2006. ISBN 0743243625

- Galil, Gershon. The Chronology of the Kings of Israel and Judah. Brill Academic Publishers, 1996. ISBN 9004106111

- Keller, Werner. The Bible as History. Bantam, 1983. ISBN 0553279432

- Miller, J. Maxwell, and John H. Hayes. A History of Ancient Israel and Judah. Westminster John Knox Press, 1986. ISBN 066421262X

- Thiele, Edwin R. The Mysterious Numbers of the Hebrew Kings. Kregel Academic & Professional; Reprint edition, 1994. ISBN 082543825X

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.