Rennes-le-Château

| Commune of Rennes-le-Château | |

| View of the Tour Magdala | |

| Location | |

| Longitude | 02.263333333 |

| Latitude | 42.9280555556 |

| Administration | |

|---|---|

| Country | |

| Region | Languedoc-Roussillon |

| Department | Aude |

| Arrondissement | Limoux |

| Canton | Couiza |

| Mayor | Alexandre Painco |

| Statistics | |

| Population² (2019) |

93 |

| - Density (2019) | 6.3/km² |

| ¹ French Land Register data, which excludes lakes, ponds, glaciers > 1 km² (0.386 sq mi or 247 acres) and river estuaries. | |

| ² Population sans doubles comptes: single count of residents of multiple communes (e.g. students and military personnel). | |

Rennes-le-Château (Rènnas del Castèl in Occitan) is a small medieval castle village and a commune located in the Languedoc region of southwestern France. It is known internationally, and receives tens of thousands of visitors per year, for being at the center of various conspiracy theories.

Starting in the 1950s, a local restaurant owner, in order to increase business, had spread rumors of a hidden treasure found by a nineteenth century priest. The story achieved national fame in France, and was then enhanced and expanded by various authors, who claimed that the priest, Father Bérenger Saunière, had found proof of a secret society known as the Priory of Sion. The story and society were later proven to be a hoax, but became the origin for hypotheses in documentaries and bestselling books such as Holy Blood Holy Grail and the fiction thriller The Da Vinci Code.

The village is still considered to be packed with clues to an alternate view of religious history that has long inspired the imagination of visitors and writers.

History

Mountains frame both ends of the region—the Cevennes to the northeast and the Pyrenees to the south. The area is known for its beautiful scenery, with jagged ridges, deep river canyons and rocky limestone plateaus, with large caves underneath. Like many European villages, it has a complex history.

It is the site of a prehistoric encampment, and later a Roman colony (possibly an oppida, but no traces have been found of ramparts, and it is thought more likely to have been a Roman villa or even a wayside temple, such as is confirmed to have been built at Fa, no more than 5 km (3.1 mi) west of Couiza).

Rennes-le-Château was a Visigoth site during the sixth and seventh centuries, during the trying period when the Visigoths had been defeated by the Frankish King Clovis I and had been reduced to Septimania. However, the claim that Rennes-le-Château was the capital of the Visigoths is an exaggeration: it was Narbonne that held that position. This claim can be traced back to an anonymous document—actually written by Nöel Corbu—entitled L'histoire de Rennes-le-Château, which was deposited at the Departmental Archives at Carcassonne, on June 14, 1962. The assertion of Visigothic importance of Rennes-le-Château is drawn from one source: A monograph by Louis Fédié, entitled "Rhedae," La Cité des Chariots, which was published in 1876. Monsieur Fédié's assertions concerning the population and importance of Rennes-le-Château have been contradicted by archaeology and the work of more recent historians.[1][2]

The site was also the location of a medieval castle, which was definitely in existence by 1002.[3] However, nothing remains above ground of this medieval structure—the present ruin is from the seventeenth or eighteenth century. Several castles situated in the surrounding region in the Languedoc were central to the battle between the Catholic church and the Cathars at the beginning of the thirteenth century. Other castles guarded the volatile border with Spain. Whole communities were wiped out during the campaigns of the Catholic authorities to rid the area of the Cathars during the Albigensian Crusades.

Church of Mary Magdalene

The earliest church of which there is any evidence on the site of the present church may be as old as the eighth century. However, this original church was almost certainly in ruins during the tenth or eleventh century, when another church was built upon the site—remnants of which can be seen in Romanesque pillared arcades on the north side of the apse.

It is this tenth or eleventh century church that had survived in poor condition. (An architectural report of 1845 reporting that it required extensive repairs.) This second church was renovated in the late 1800s by the local priest, Bérenger Saunière, though the source of his funds at the time was controversial (see below) and some of the additions to the church appear unusual to modern eyes.

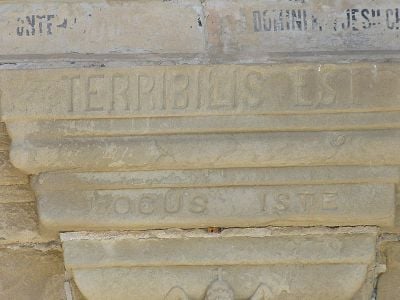

One of the new features added to the church was an inscription above the front door: Terribilis est locus iste (meaning, "This place is scary/horrible/terrible"). Inside the church, one of the added figures was of a devil holding up the holy water stoup (rare, but other examples exist in other churches around France). The decorations chosen by Saunière were selected from a catalogue published by Giscard, sculptor and painter in Toulouse who—among other things—offered statues and sculptural features for church refurbishment. Pages from the Catalogue of Giscard and Co were reproduced in a book by Marie de Saint-Gély first published in 1989.[4] The figures and statues chosen by Saunière were not specially made.[1]

Saunière also funded the construction of another structure dedicated to Mary Magdalene, named after his church, a tower on the side of a nearby mountain which he used as his library, with a promenade linking it to the Villa Bethanie, which was not actually used by the priest. He stated during his trial that it was intended for retired priests.[5]

The inscription above the entrance is taken from the Common Dedication of a Church, which in full reads [Entrance Antiphon Cf. Gen 28:17]: "This is a place of awe; this is God's house, the gate of heaven, and it shall be called the royal court of God." The first part of the passage is situated in the entrance of the church - the rest of the passage is actually inscribed over the arches on the two doors of the church. Sauniere's church was re-dedicated in 1897 by his bishop, Monsigor Billard, following Sauniere's renovations and redecorations.[5][6]

Modern fame

Until recently, Rennes-le-Château was a tiny and obscure village but by 2006 the area was receiving approximately 100,000 tourists each year. Much of the modern reputation of Rennes-le-Château rises from rumors dating from the mid-1950s concerning a local nineteenth-century priest. Father Bérenger Saunière had arrived in the village in 1885, and had acquired and spent large sums of money during his tenure from selling masses and receiving donations, funding several building projects, including the Church of Mary Magdalene.[7][8][1] The source of the wealth had long been a topic of conversation, and rumors within the village ranged from the priest finding a treasure to spying for the Germans during World War I. During the 1950s, these rumors were given wide local circulation by Noël Corbu, a local man who had opened a restaurant in Saunière's former estate (L'Hotel de la Tour), and hoped to use the stories to attract business.[8]

From that point on Rennes-le-Château became the centre of conspiracy theories claiming that Saunière uncovered hidden treasure and/or secrets about the history of the Church, which could potentially threaten the foundations of Catholicism. The area has become the focus of increasingly sensational claims involving the Knights Templar, the Priory of Sion, the Rex Deus, the Holy Grail, the treasures of the Temple of Solomon, the Ark of the Covenant, ley lines, and sacred geometry alignments.

The Saunière story

The story began when Noël Corbu wanted to attract visitors to his local hotel in Rennes-le-Château, by spreading the claim that Bérenger Saunière had become rich by finding a royal treasure inside one of the pillars in his church in the late 1800s. The first newspapers started printing Corbu's story in 1956. This ignited a flame: visitors with shovels flooded the town, and Corbu got what he wanted.

However, this also attracted a number of persons such as Pierre Plantard. His childhood dream was to play a vital role in the history of France, so he and some friends concocted an elaborate hoax. It involved planting fabricated documents in France's Bibliothèque nationale de France, to imply that Plantard was a descendant of a French royal dynasty, which would somehow mean that he was supposed to be declared King of France. The fabricated documents also mention the ancient Priory of Sion, which was supposedly 1,000 years old, but was in fact the name of an organization that Plantard founded himself in 1956 with three of his friends.[1]

No serious journalists who investigated the story found it plausible enough to write about, so Plantard asked his friend, Gérard de Sède, to write a book to give more credence to the story.[9] They chose the already rumor-rich area of Rennes-le-Chateau as their setting, and L’Or de Rennes (The Gold of Rennes), later published as Le Trésor Maudit de Rennes-le-Château(The Accursed Treasure of Rennes-le-Chateau) came out in 1967 and was an instant success.[10] The book presented Latin documents forged by Plantard's group, alleging that these were medieval documents that had been found by Saunière in the nineteenth century. One of the documents had multiple encrypted references to the Priory of Sion, thereby attempting to prove that the society was older than its actual creation date of 1956.

In 1969, a British actor and science-fiction writer by the name of Henry Lincoln read the book, dug deeper, and wrote his own books on the subject, pointing out his discovery of hidden codes in the parchments. One of the codes involved a series of raised letters in the Latin message, which when read off separately, spelled out in French: a dagobert ii roi et a sion est ce tresor et il est la mort. (translation: This treasure belongs to King Dagobert II and to Sion, and it is death.).

Lincoln created a series of BBC Two documentaries about his theories in the 1970s, and then in 1982, co-wrote The Holy Blood and the Holy Grail with Michael Baigent and Richard Leigh. Their book expanded upon the Rennes-le-Château story to further imply that the descendents of Jesus and Mary Magdelane were connected to the French royalty as perpetuated through a secret society named the Priory of Sion. This torch was then picked up and carried further in 2003 in Dan Brown's bestselling novel The Da Vinci Code, though Brown's book never mentioned Rennes-le-Château by name.

The extraordinary popularity of The Da Vinci Code has reignited the interest of tourists, who come to the village to see sites associated with Saunière and Rennes-le-Château. The "Visigothic pillar" where Sauniere was said to have found the documents is on display in the village's Saunière Museum. The pillar was set up by Saunière in 1891 as part of his shrine to Our Lady of Lourdes. René Descadeillas doubted the allegation that the pillar originated from Saunière's church, since a Church report drawn up by the diocesan architect Guiraud Cals in 1853 failed to mention the existence of any altar pillar.[7]

The source of Saunière's wealth

The stories of Saunière's mysteries were based on little more than a minor scandal involving the sale of masses, which eventually led to the disgrace of both Saunière and his bishop. His wealth was short-lived, and he died relatively poor. Official records of a trial against Saunière on August 23, 1910 revealed his fortune at the time to have been 193,150 francs, which he claimed to be spending on parish works. Yet, in order to have gained this wealth through the selling of masses, the priest would have had to sell over 20 masses per day for the 25 years prior to the trial, more than he could have performed. Sauniere claimed that he performed masses for which he was paid and that other funds came from local donations.[8][1][6][7]

This evidence was published by French Editions Belisane from the early 1980s onwards, with evidence from the archives in the possession of Antoine Captier, including Saunière's correspondence and notebooks. The minutes of the ecumenical trial between Saunière and his bishop between 1910–1911 are located in the Carcassonne Bishopric. Or as Ed Bradley said on a 2006 episode of the American news program 60 Minutes: "The source of the wealth of the priest of Rennes-le-Chateau was not some ancient mysterious treasure, but good old fashioned fraud."[11]

Archaeologist Paul Bahn commented:

The myth of Rennes-le-Château – so beloved of occultists and ‘aficionados’ of the "Unexplained" – is ranked with the Bermuda Triangle, Atlantis and ancient astronauts as a source of ill-informed and lunatic books. [12]

Likewise another archaeologist Bill Putnam, co-author with John Edwin Wood of The Treasure of Rennes-le-Château, A Mystery Solved (2003, 2005) has dismissed all of the popular allegations as pseudo-history.

Laura Miller, contributor to the New York Times books section noted how the village of Rennes-le-Château had become "a town that had become the French equivalent of Roswell or Loch Ness as a result of popular books by Gérard de Sède."[13]

As for the relationship with the fictional Priory of Sion and Plantard's hoax, multiple factors disproved those theories as well. Philippe de Chérisey–who helped Plantard with his fraud–admitted having fabricated the historical documents. The decoded messages embedded within the forged documents were shown to have been written in modern French. Gérard de Sède, another of the conspirators who had written the book Le Tresor Maudit, also wrote a book denouncing the fraud, and this was further confirmed by his son.[14]

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Bill Putnam and John Edwin Wood, The Treasure of Rennes-le-Château, a Mystery Solved (Sutton Publishing Limited: 2005, ISBN 0750942169).

- ↑ Jean Fourié, Rennes-le-Château: L’Histoire de Rennes-le-Château antérieure à 1789, Notes Historiques, Editions Jean Bardou, Esperaza, 1984.

- ↑ Abbé Sabarthès, Dictionnaire topographique du Département de l'Aude, comprenant les noms de lieux anciens et modernes (Wentworth Press, 2018 (original 1912), ISBN 978-1385965757).

- ↑ Marie de Saint-Gély, Bérenger Saunière, prêtre Rennes-le-Château 1885-1917 (Éditeur Claude Boumendil, 1989, ISBN 978-2902296873).

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Jacques Rivière, Le Fabuleux trésor de Rennes-le-Château (Editions Belisane: 1983, ISBN 978-2902296422).

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Abbé Bruno de Monts, Bérenger Sauniére curé à Rennes-le-Château 1885-1909 (Belisane, Collection les amis de Bérenger Sauniére: 2000, ISBN 2902296851).

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 René Descadeillas, Mythologie du Trésor de Rennes: Histoire Veritable de L'Abbé Saunière, Curé de Rennes-Le-Château (Savary: 1991 (original 1974), ISBN 9782950097163).

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Jean-Jacques Bedu, Rennes-Le-Château: Autopsie d'un mythe (Loubatières: 1990, ISBN 9782862663722)

- ↑ Jean-Luc Chaumeil, Chantal Low (trans.), The Priory of Sion: Shedding Light on the Treasure and Legacy of Rennes-Le-Chateau and the Priory of Sion (Avalonia, 2010, ISBN 978-1905297412).

- ↑ Gerard de Sède, Bill Kersey (trans.), The Accursed Treasure of Rennes-le-Chateau (Dek Publishing, 2001, ISBN 0954152700).

- ↑ Daniel Schorn, The Priory of Sion 60 Minutes hosted by Ed Bradley, April 30, 2006. Retrieved February 24, 2023.

- ↑ Paul G Bahn, The ruins of a mystery, Times Literary Supplement, March 29, 1991. Retrieved February 24, 2023.

- ↑ Laura Miller, The Last Word: The Da Vinci Con The New York Times, February 22, 2004. Retrieved February 24, 2023.

- ↑ The Real Da Vinci Code, Channel 4 Television, presented by Tony Robinson, transmitted on February 3, 2005.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Bedu, Jean-Jacques. Rennes-Le-Château: Autopsie d'un mythe Loubatières: 1990. ISBN 9782862663722

- Chaumeil, Jean-Luc, Chantal Low (trans.). The Priory of Sion: Shedding Light on the Treasure and Legacy of Rennes-Le-Chateau and the Priory of Sion. Avalonia, 2010. ISBN 978-1905297412

- Descadeillas, René. Mythologie du trésor de Rennes: Histoire véritable de l'abbé Saunière curé de Rennes-le-Château. Savary: 1991 (original 1974). ISBN 9782950097163

- de Monts, Abbé Bruno. Bérenger Sauniére curé à Rennes-le-Château 1885-1909. Belisane, Collection les amis de Bérenger Sauniére: 2000. ISBN 2902296851

- de Saint-Gély, Marie. Bérenger Saunière, prêtre Rennes-le-Château 1885-1917. Éditeur Claude Boumendil, 1989. ISBN 978-2902296873

- de Sède, Gerard, Bill Kersey (trans.). The Accursed Treasure of Rennes-le-Chateau. Dek Publishing, 2001. ISBN 0954152700

- Putnam, Bill, and John Edwin Wood. The Treasure of Rennes-le-Chateau, A Mystery Solved. Sutton Publishing Limited: 2005. ISBN 0750942169

- Rivière, Jacques. Le fabuleux trésor de Rennes-le-Château!: Le secret de l'abbé Saunière . Editions Belisane: 1983. ISBN 978-2902296422

- Sabarthès, Abbé. Dictionnaire topographique du Département de l'Aude, comprenant les noms de lieux anciens et modernes. Wentworth Press, 2018 (original 1912). ISBN 978-1385965757

External links

All links retrieved February 23, 2023.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.