| République d'Haïti Repiblik d Ayiti Republic of Haiti |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||

| Motto: Liberté, Égalité, Fraternité [1] | ||||||

| Anthem: La Dessalinienne |

||||||

| Capital (and largest city) | Port-au-Prince 18°32′N 72°20′W | |||||

| Official languages | French, Haitian Creole, | |||||

| Ethnic groups | 95% black, 5% mulatto and white | |||||

| Demonym | Haitian | |||||

| Government | Unitary semi-presidential republic under an interim government | |||||

| - | Transitional Presidential Council | Edgard Leblanc Fils Fritz Jean |

||||

| - | Prime Minister | Garry Conille (acting) | ||||

| Formation | ||||||

| - | French colony declared (Treaty of Ryswick) |

30 October 1697 | ||||

| - | Independence declared | 1 January 1804 | ||||

| - | Independence recognized from France | 17 April 1825 | ||||

| Area | ||||||

| - | Total | 27,750 km² (140th) 10,714 sq mi |

||||

| - | Water (%) | 0.7 | ||||

| Population | ||||||

| - | 2024 estimate | 11,753,943[2] (83rd) | ||||

| - | Density | 382/km² (32nd) 989.7/sq mi |

||||

| GDP (PPP) | 2023 estimate | |||||

| - | Total | |||||

| - | Per capita | |||||

| GDP (nominal) | 2023 estimate | |||||

| - | Total | |||||

| - | Per capita | |||||

| Gini (2012) | 41.1[4] | |||||

| Currency | Gourde (HTG) |

|||||

| Time zone | (UTC-5) | |||||

| Internet TLD | .ht | |||||

| Calling code | +509 | |||||

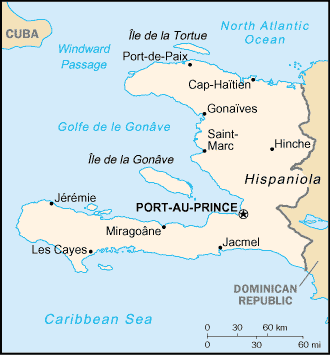

Haiti, officially the Republic of Haiti, is a country on the Caribbean island of Hispaniola, which it shares with the Dominican Republic. Haiti also includes many smaller islands such as La Gonâve, La Tortue (Tortuga), Les Cayemites, Île de Anacaona, and La Grande Caye. Ayiti (Haiti) was the indigenous Taíno name for the island. Its highest point is Chaine de la Selle, at 2,680 meters. The total area of Haiti is 10,714 square miles (27,750 km²) and its capital is Port-au-Prince.

A former French colony, Haiti became the first independent black republic and the only nation ever to form from a successful slave rebellion. Haiti became the second non-native country in the Americas (after the United States) to declare its independence, in 1804. Once France's richest colony, the island nation has been hindered by political, social, and economic problems. As a result of mismanagement, very few natural resources exist, as exemplified by the extent of Haiti's deforestation.

Its history has been one of extreme political instability marked by dictatorships and coups. Most presidents seem to have been motivated by personal gain as opposed to leading the country toward growth and development. The country has consistently ranked as one of the most corrupt nations according to the Corruption Perceptions Index, a measure of perceived political corruption.

Geography

Haiti comprises the western third of the island of Hispaniola, west of the Dominican Republic and between the Caribbean Sea and the North Atlantic Ocean. Haiti's geographic coordinates are at a longitude of 72° 25′ west and a latitude of 19° 00′ north. The total area is 27,750 km² of which 27,560 km² is land and 190 km² is water. This makes Haiti slightly smaller than the U.S. state of Maryland. Haiti has 1,771 km of coastline and a 360 km-border with the Dominican Republic. There has been a dispute between the United States and Haiti regarding Navassa Island (Navasse), which both countries claim. The Haitian claim relies on documentation that Navassa became part of Haiti after a 1697 agreement between France and Spain that gave France the western third of Hispaniola plus nearby islands, including Navassa Island. The United States claims the island pursuant to its own Guano Islands Act of 1856.

Haiti's lowest elevation is at sea level; its highest point is Pic la Selle at 2,680 m. Except for part of Haiti's longest river, the Artibonite, there are no navigable rivers; the largest lake is Etang Saumâtre, a salt-water body located in the southern region. Haiti also contains several islands. The famous island of Tortuga (Île de la Tortue) is located off the coast of northern Haiti. The arrondissement of La Gonâve is located on the island of the same name, in the Gulf of Gonave. Gonave Island is moderately populated by rural villagers. Île à Vache (Island of The Cow) is located off the tip of southwestern Haiti. It is a rather lush island with many beautiful sights. Also parts of Haiti are the Cayemites and Ile de Anacaona.

Haiti has a tropical climate with an average temperature of 81°F (27°C). Rainfall varies greatly and ranges from 144 inches in the western end of the southern peninsula to 24 inches on the western end of the northern peninsula. Haiti is vulnerable to hurricanes and tropical storms during the Atlantic Hurricane season.

In the early twentieth century, Haiti was a lush tropical paradise, with 60 percent of its original forest covering the lands and mountainous regions. Since then, the population has cut down most of its original forest cover, and in the process has destroyed fertile farmland soils, while contributing to desertification. Only some pine at high elevations and mangroves remain due to their inaccessibility. Erosion has been severe in the mountainous areas. Pictures from space show the glaringly stark difference in forestation between Haiti and the neighboring Dominican Republic. Most Haitian logging is done to produce charcoal, the country's chief source of fuel. The plight of Haiti's forests has attracted international attention, and has led to numerous reforestation efforts, but these have met with little success.

About 40 percent of the land area is used for plantations which grow crops such as sugar cane, rice, cotton, coffee, and cacao. Minerals such as bauxite, salt, gold, and copper exist although they are not in viable quantities.

Environmental issues

In addition to soil erosion, the deforestation has also caused periodic flooding.

Tropical reefs that surround Haiti are threatened by silt carried out to the ocean due to deforestation. Many of Haiti's native animals were hunted to extinction and the only common remaining wildlife is the Caiman and flamingo.

History

The island of Hispaniola, of which Haiti occupies the western third, was originally inhabited by the Taíno Arawak people. Christopher Columbus landed at Môle Saint-Nicolas on December 5, 1492, and claimed the island for Spain. Nineteen days later, the Santa Maria ran aground near the present site of Cap-Haitien; Columbus was forced to leave 39 men, founding the settlement of La Navidad. Ayiti, which means "mountainous land," is a name used by its early inhabitants, the Taino-Arawak people, who also called it Bohio, meaning "rich villages," and Quisqueya, meaning "high land."

The Taínos were a seafaring branch of the South American Arawaks. Taíno means "the good" or "noble" in their language. A system of cacicazgos (chiefdoms) existed, called Marien, Maguana, Higuey, Magua, and Xaragua, which could be subdivided. The cacicazgos were based on a system of tribute, consisting of the food grown by the Taíno. Among the cultural signs that they left were cave paintings around the country, which have become touristic and nationalistic symbols of Haiti. Xaragua is modern day Leogane, a city in the southwest. Most of the Taino-Arawak people are extinct, the few survivors having mixed genetically with African slaves and European conquerors.

Colonial rule

Enslavement, harsh treatment of the natives, and especially epidemic diseases such as smallpox caused the Taino population to plummet over the next quarter-century. In response, the Spanish began to import African slaves to search for gold on the island. Spanish interest in Hispaniola waned after the 1520s, when vast reserves of gold and silver were discovered in Mexico and South America.

Fearful of pirate attacks, the king of Spain in 1609 ordered all colonists on Hispaniola to move closer to the capital city, Santo Domingo. However, this resulted in British, Dutch, and French pirates establishing bases on the island's abandoned northern and western coasts. French settlement of the island began in 1625, and in 1664 France formally claimed control of the western portion of the island. By the 1697 Treaty of Ryswick, Spain ceded the western third of Hispaniola to France. France named its new colony Saint-Domingue.

While the Spanish side of the island was largely neglected, the French side prospered and became the richest colony in the Western Hemisphere, exporting large amounts of sugar and coffee. French colonial society contained three population groups: Europeans (about 32,000 in 1790) who held political and economic control; the gens de couleur, some 28,000 free blacks (about half of which had mulatto background) who faced second-class status; and the slaves, who numbered about 500,000.[5] (Living outside French society were the maroons, escaped ex-slaves who formed their own settlements in the highlands.) At all times, a majority of slaves in the colony were African-born, as the very brutal conditions of slavery prevented the population from experiencing growth through natural increase. African culture thus remained strong among slaves until the end of French rule.

Revolution

Inspired by the French Revolution, the gens de couleur (free blacks) pressed the colonial government for expanded rights. In October 1790, 350 revolted against the government. On May 15, 1791, the French National Assembly granted political rights to all blacks and mulattoes who had been born free—but did not change the status quo regarding slavery. On August 22, 1791, slaves in the north rose against their masters near Cap-Français (now Cap-Haïtien). This revolution spread rapidly and came under the leadership of Toussaint L'Ouverture, who is commonly referred to as the "Black Napoleon." He soon formed alliances with the gens de couleur and the maroons, whose rights had been revoked by the French government in retaliation for the uprising.

Toussaint's armies defeated the French colonial army, but in 1794 joined forces with it, following a decree by the revolutionary French government that abolished slavery. Under Toussaint's command, the Saint-Domingue army then defeated invading Spanish and British forces. This cooperation between Toussaint and French forces ended in 1802, however, when Napoleon sent a new invasion force designed to subdue the colony; many islanders suspected the army would also reimpose slavery. Napoleon's forces initially were successful at fighting their way onto the island, and persuaded Toussaint to a truce. He was then betrayed, captured, and died in a French prison. Toussaint's arrest and the news that the French had reestablished slavery in Guadeloupe, led to the resumption of the rebellion, under the leadership of Jean-Jacques Dessalines and Henri Christophe, two of Toussaint's generals. Napoleon's forces were outsmarted by the combination of Jean-Jacques Dessalines, Henri Christophe, and Alexandre Petion, the "Generals of the Revolution."

Independence

Dessalines's armies won their final and decisive victory over the French forces at the Battle of Vertières on November 18, 1803, near Cap-Haitien. On January 1, 1804 the nation declared its independence, securing its position as the second independent country in the New World, and the only successful slave rebellion in world history. Dessalines was its first ruler. The name Haiti was chosen in recognition of the old Arawak name for the island, Ayiti.

The Haitian Revolution is thought to have inspired numerous slave revolts in the Caribbean and United States. The blockade was virtually total. The Vatican withdrew its priests from Haiti, and did not return them until 1860. France refused to recognize Haiti's independence until it agreed to pay an indemnity of 150 million francs, to compensate for the losses of French planters in the revolutions, in 1833. Payment of this indemnity put the government deeply in debt and crippled the nation's economy.

In 1806, Dessalines, the new country's leader, was murdered in a power struggle with political rivals who thought him a tyrant. The nation divided into two parts, a southern republic founded by Alexandre Pétion (mulatto), becoming the first black-led republic in the world,[6] and a northern kingdom under Henri Christophe. The idea of liberty in the southern republic was as license, a fondness for idleness shared by elite and peasant. Christophe believed that liberty was the opportunity to show the world that a black nation might be equal, if not better, than the white nations. Consequently, he worked the field hands under the same unrelenting military system that Toussaint had developed and that Dessalines tried to continue. He also built more than 100 schools, eight palaces, including his capital Sans Souci and the massive Citadelle Laferrière, the largest fortress in the Western hemisphere.

In August 1820, King Henri I (Henri Christophe) suffered a stroke that left him partially paralyzed. When the news spread of his infirmities, the whispers of rebellion, deceit, and treachery began. On October 2, 1820, the military garrison at St. Marc led a mutiny that sparked a revolt. The mutiny preempted a conspiracy of some of Christophe's most loyal generals. Some of his trusted aides took him from the palace of Sans-Souci to his Citadel, to await the inevitable confrontation with the rebels. Christophe ordered his attendants to dress him in his formal military uniform and for two days desperately tried to raise the strength to lead out his troops. Finally, he ordered his doctor to leave the room. Shortly after he left, Christophe raised his pistol and shot himself through the heart.

Following Christophe's death, the nation was reunited as the Republic of Haiti under Jean-Pierre Boyer, Petion's successor. Boyer invaded the Spanish colony of Santo Domingo and united the entire island of Hispaniola under Haitian rule, until 1844 when the Dominican Republic declared its independence from Haiti.

American occupation

Throughout the nineteenth century, the country was ruled by a series of presidents, most of whom remained in office only briefly. Meanwhile, the country's economy was gradually dominated by foreigners, particularly from Germany. Concerned about German influence, and disturbed by the lynching of President Guillaume Sam by an enraged crowd, the United States invaded and occupied Haiti in 1915. The U.S. imposed a constitution (written by future president Franklin D. Roosevelt) and applied an old system of compulsory corvée labor to everyone. Previously this system had been applied only to members of the poor, black majority. The occupation had many long-lasting effects on the country. United States forces built schools, roads, and hospitals, and launched a campaign that eradicated yellow fever from the island. Unfortunately, the establishment of these institutions and policies had long-lasting negative effects on Haiti's economy.

Sténio J. Vincent, the president from 1930 to 1941, made attempts to improve living conditions and modernize agriculture. Vincent decided to remain in office beyond the expiration of his second term, but was forced out in 1939. Élie Lescot was elected president by the Haitian legislature in 1941, but was subsequently overthrown in 1946, by the military.

In 1946, Dumarsais Estimé became the country's first black president since the American occupation began. His efforts at reform sparked disorder, and when he attempted to extend his term of office in 1950 (as most previous presidents had done) there was a coup, followed by the second formal Military Council of Government led by Paul Magloire.

In 1957, Dr. François Duvalier ("Papa Doc") came to power in the country's first universal suffrage election; many believed this outcome was manipulated by the army. In 1964, he declared himself president for life. Duvalier maintained control over the population through his secret police organization, the Volunteers for National Security—nicknamed the Tonton Macoutes ("bogeymen") after a folkloric villain. This organization drew international criticism for its harsh treatment of political adversaries, both real and suspected. Upon Duvalier's death in 1971, he was succeeded by his 19 year-old son Jean-Claude Duvalier (nicknamed "Baby Doc") as Haiti's new president for life. The younger Duvalier regime became notorious for corruption, and was deposed in 1986, ushering in a new period of upheaval.

The unraveling of the Duvalier regime began with a popular movement supported by the local church and set in motion by the visit of Pope John Paul II in 1983, who before embarking his plane gave a rousing speech ending with the exclamation: "Things must change here!"[7] In 1984, anti-government riots broke out throughout the nation and the Haitian Catholic Bishops' Conference initiated a literacy program designed to prepare the Haitian public for participation in the electoral process.

Aristide

The priest Jean-Bertrand Aristide was elected president in 1990, but was deposed in a coup shortly after his inauguration in 1991. There followed three years of brutal control by a military junta led by Raoul Cedras, before a second American invasion and occupation in 1994 returned Aristide to power. One of the first acts of the re-installed government of Aristide was to disband the army, to great popular acclaim.[8]

Aristide was succeeded by a one-time ally and former prime minister, René Préval, in 1996. While Aristide was the first democratically elected president in Haitian history, Préval's administration was most notable for the fact that he was the first person in Haiti's history to constitutionally succeed a president and then serve a complete term, leaving office voluntarily at the prescribed time. Every previous president had either died in office, been assassinated or deposed, overstayed his prescribed term, or been installed by a foreign power.

Aristide returned to office in 2001 after elections that were boycotted by many of his opponents, who accused his party (Fanmi Lavalas) of counting votes improperly in a previous senatorial election, as well as threatening critics. Aristide denied the charges and accused his opponents of accepting U.S. assistance and plotting to overthrow his government. The opposition mostly denied this, but many of its members continually called for his early resignation.

Post-Aristide era

In February 2004, following months of large-scale protests against what critics charged was an increasingly corrupt and violent rule, violence spread through Haiti, involving conflicts between the government and various rebel groups. Under pressure from both foreign governments and internal sources, Aristide left the country for the Central African Republic on February 29. Aristide claimed that he had been kidnapped by agents of the United States government, while the United States and some of Aristide's own security agents claimed that Aristide had agreed to leave the country willingly and that it had escorted him to Africa for his own protection. As Aristide departed the country, many members of his government fled or went into hiding, and the United States again sent U.S. Marines into Port-au-Prince. After Aristide's departure, Supreme Court Chief Justice Boniface Alexandre succeeded to the presidency appointed by a council of elders and supported by the United States, Canada, and France.

In the months following the February Coup, the country was engulfed in violence between the interim government's forces and Lavalas supporters, and many members of the Lavalas party were either sent to jail, exiled, or killed. Much of the violence began after police of the interim force began shooting at peaceful Lavalas demonstrations in mid-2004. Over 10,000 workers in Haitian civil enterprises lost their jobs following the coup.

Amidst the continuing political chaos, a series of natural disasters hit Haiti. In 2004 Tropical Storm Jeanne skimmed the north coast, leaving 3,006 people dead in flooding and mudslides, mostly in the city of Gonaïves. In 2008 Haiti was again struck by tropical storms; Tropical Storm Fay, Hurricane Gustav, Hurricane Hanna and Hurricane Ike all produced heavy winds and rain.

On January 12, 2010, at 4:53 pm local time, Haiti was struck by a magnitude-7.0 earthquake. The earthquake was reported to have left between 160,000 and 300,000 people dead and up to 1.6 million homeless, making it one of the deadliest natural disasters ever recorded.[9] The situation was exacerbated by a subsequent massive cholera outbreak.

General elections had been planned for January 2010 but were postponed due to the earthquake. Michel Martelly was declared the winner when elections took place in 2011. After continuing political wrangling with the opposition and allegations of electoral fraud, Martelly agreed to step down in 2016 without a successor in place.

After numerous postponements, partly owing to the effects of devastating Hurricane Matthew, elections were held in November 2016. The victor, Jovenel Moïse of the Haitian Tèt Kale Party, was sworn in as president in 2017. Protests began on 7 July 2018, in response to increased fuel prices. Over time these protests evolved into demands for the resignation of president Moïse.

On July 7, 2021, President Moïse was assassinated in an attack on his private residence, and First Lady Martine Moïse was hospitalized.[10] Amid the political crisis, the government of Haiti installed Ariel Henry as both the acting prime minister and acting president on July 20, 2021.

On August 14, 2021, Haiti suffered another huge earthquake, with many casualties. The earthquake has also damaged Haiti's economic conditions and led to a rise in gang violence which by September 2021 had escalated to a long-lasting full-blown gang war and other violent crimes within the country. In March 2022, Haiti still had no president, no parliamentary quorum, and a dysfunctional high court due to a lack of judges.

In March 2024, Ariel Henry was prevented by gangs from returning to Haiti, following a visit to Kenya.[11] Henry agreed to resign once a transitional government had been formed.

On April 25, 2024 Transitional Presidential Council of Haiti took over the Governance of Haiti, scheduled to stay in power until 2026. Michel Patrick Boisvert was named interim Prime Minister.[12]

Politics

Politics of Haiti takes place in a framework of a presidential republic, pluriform multiparty system whereby the President of Haiti is head of state directly elected by popular vote. The Prime Minister acts as head of government, and is appointed by the President from the majority party in the National Assembly. Executive power is exercised by the President and Prime Minister who together constitute the government. Legislative power is vested in both the government and the two chambers of the National Assembly of Haiti. The government is organized unitarily, thus the central government delegates powers to the departments without a constitutional need for consent. The current structure of Haiti's political system was set forth in the Constitution of March 29, 1987.

Economy

Despite its tourism industry, Haiti is one of the poorest countries in the Americas, with corruption, political instability, poor infrastructure, lack of health care and lack of education cited as the main causes. It remains one of the least-developed countries in the Western Hemisphere and one of the poorest in the world. Comparative social and economic indicators show Haiti falling behind other low-income developing countries (particularly in the hemisphere) since the 1980s. About 80 percent of the population lives in abject poverty, ranking the country second-to-last in the world for that metric. Unemployment is high and many Haitians seek to emigrate. Trade declined dramatically after the 2010 earthquake and subsequent outbreak of cholera.

Nearly 70 percent of all Haitians depend on the agricultural sector, which consists mainly of small-scale subsistence farming The country has experienced little job creation over the past decade, although the informal economy is growing.

Demographics

Ninety-five percent of Haitians are of predominantly African descent. The remainder are White or of Mulatto descent, with some of Levantine, Spanish or mestizo heritage. A significant number of Haitians is believed to possess African and Taino/Arawak heritage due to the history of the island, however the number of native-descended Haitians is not known. There is a very small percentage within the minority who are of Japanese or Chinese origin.

As with many other poor Caribbean nations, there is a large diaspora, which includes a lot of illegal immigration to nearby countries. Millions of Haitians live abroad, chiefly in the Dominican Republic, Bahamas, Cuba, Puerto Rico, Canada, France, and the United States.

There are large numbers of Haitians who inhabit the "Little Haiti" section of Miami. In New York City, the Brooklyn neighborhoods of Flatbush, Crown Heights, and Canarsie are home to many Haitians. In New York's borough of Queens, Jamaica, Queens Village and Cambria Heights have large Haitian populations. Many successful Haitians move east to Long Island, where Elmont and other towns have seen many new residents. Other enclaves that contain Haitians include Cambridge, Massachusetts, Chicago, Illinois, and Newark, New Jersey, and its surrounding towns.

Unsanitary living conditions and a lack of running water to three-quarters of all Haitians cause problems such as malnutrition, infectious and parasitic diseases, an infant mortality rate that is the highest in the Western Hemisphere, and the prevalence of HIV/AIDS. This, along with a shortage of medical staff and medicines is responsible for the high death rate in Haiti.

Education in Haiti is free and compulsory for children between the ages of 6 and 11. In rural areas especially, education is not possible due to the distance a child must travel to the nearest school as well as the cost of books, uniforms and the availability of teachers. This has resulted in a literacy rate of only about 55 percent nationwide.

Along with two other private institutions, the University of Haiti is the only public institution of higher education. Many of Haiti's university level students leave Haiti and to foreign universities.

Culture

Language

Haiti's official languages are French and Haitian Creole (Kreyòl Ayisyen). Nearly all Haitians speak the latter, a creole based primarily on French and African languages, with some English, Taíno, Portuguese, and Spanish influences. Spanish is spoken near the border with the Dominican Republic, and is increasingly being spoken in more westward areas, as Venezuelan, Cuban, and Dominican trade influence Haitian affairs, and Haiti becomes increasingly involved in Latin American transactions.

Religion

Roman Catholicism is the state religion, which the majority of the population professes. An estimated 20 percent of the population practices Protestantism. A large percentage of the population in Haiti also practices the religion of voodoo, almost always alongside Roman Catholic observances (in most sects, it is required to become Roman Catholic first). Many Haitians deny the recognition of voodoo as a stand-alone religion and some claim it is a false religion.

Cuisine

Haitian Cuisine is influenced in large part by the methods and foods involved in French cuisine as well as by some native staples originating from African and Taíno cuisine, such as cassava, yam, and maize. Haitian food, though unique in its own right, shares much in common with that of the rest of Latin America.

Music

The music of Haiti is easily distinguished from other styles. It includes kompa, Haitian Méringue, twobadou, rasin and kadans. Other musical genres popular in Haiti include Trinidadian Soca, merengue (originating in the Dominican Republic), and zouk (a combination of kompa and music from the French Antilles). Musicians such as T-Vice and Carimi perform regularly in the United States and Québec. Sweet Micky is inarguably one of the greatest legends of Kompa music, he is called the President of Kompa. The most successful and well known Haitian musical artist of today is Wyclef Jean, who is internationally recognized for being one of the first Haitian artists to find commercial success. Another successful artist is Jean Jean-Pierre, a journalist (The Village Voice, the Gannett Newspapers, among others), a composer and producer who has produced several sold-out shows at Carnegie Hall with his Kiskeya Orchestra since 2001.

Notes

- ↑ Article 4 of the Constitution Retrieved June 7, 2024.

- ↑ CIA, Haiti: People and Society World Factbook. Retrieved June 7, 2024.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 World Economic Outlook Database, October 2023 Edition. (Haiti) International Monetary Fund. Retrieved June 7, 2024.

- ↑ Gini Index The World Bank. Retrieved June 7, 2024.

- ↑ Slavery and the Haitian Revolution Liberté, Egalité, Fraternité. Retrieved June 7, 2024.

- ↑ Haiti Country profile BBC. Retrieved June 7, 2024.

- ↑ Michele Wucker, Why the Cocks Fight: Dominicans, Haitians, and the Struggle for Hispaniola (Hill and Wang, 2000, ISBN 978-0809097135).

- ↑ Crisis in Haiti BBC News, March 3, 2004. Retrieved June 7, 2024.

- ↑ Haiti Earthquake Fast Facts CNN (January 9, 2023). Retrieved June 7, 2024.

- ↑ Evens Sanon and Danica Coto, Haiti in upheaval: President Moïse assassinated at home AP News (July 7, 2021). Retrieved June 7, 2024.

- ↑ Danica Coto, Haiti’s prime minister is locked out of his country and faces pressure to resign Associated Press News (March 8, 2024). Retrieved June 7, 2024.

- ↑ Robenson Geffrard, Les membres du Conseil présidentiel de transition ont prêté serment au Palais nationalLe Nouvelliste (April 25, 2024). Retrieved June 7, 2024.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Farmer, Paul. The Uses of Haiti. Monroe, ME: Common Courage Press, 2003. ISBN 1567512429

- Fick, Carolyn E. The Making of Haiti: The Saint Domingue Revolution From Below. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1990. ISBN 0870496670

- Heinl, Robert Debs, Nancy Gordon Heinl, and Michael Heinl. Written in Blood: The Story of the Haitian People, 1492-1995. Lanham, MD: University Press of America, 2005. ISBN 0761831770

- James, C.L.R. The Black Jacobins: Toussaint L'Ouverture and the San Domingo Revolution. New York: Vintage Books, 1989. ISBN 0679724672

- Kurlansky, Mark. A Continent of Islands: Searching for the Caribbean Destiny. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley Pub. Co., 1992. ISBN 0201523965

- Ros, Martin, Karin H. Ford (trans.). Night of Fire: The Black Napoleon and the Battle for Haiti. New York: Sarpedon, 1994. ISBN 0962761389

- Tata, Robert J. Haiti, Land of Poverty. Washington, DC: University Press of America, 1982. ISBN 0819124397

- Wucker, Michele. Why the Cocks Fight: Dominicans, Haitians, and the Struggle for Hispaniola. Hill and Wang, 2000. ISBN 978-0809097135

External links

All links retrieved June 22, 2024.

- Constitution of Haiti - unofficial translation by Georgetown University

- Embassy of Haiti in Washington D.C.

- Haiti World Factbook

- Haiti U.S. Department of State

- Haiti country profile BBC

- Haiti Human Rights Watch.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.