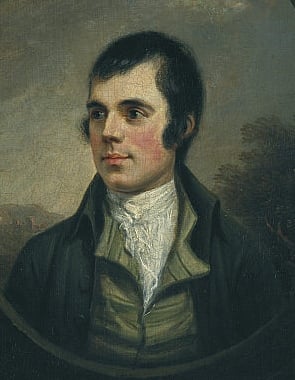

Robert Burns

Robert Burns (January 25, 1759 – July 21, 1796) was a Scottish poet and songwriter, who is widely regarded as the national poet of Scotland, and the best known poet to have ever written in the Scots language. Burns, however, was much more than just a hero to Scotsmen; he wrote frequently in English and in an English/Scots dialect, making his poems accessible to a wide audience and ensuring his enduring fame. He was a vigorous social and political critic, becoming a champion for the causes of civil and economic equity for all people after witnessing his father's miserable struggles through poverty. From humble origins and meager education, Burns has become an icon of an impoverished member of the working class rising to intellectual grandeur. By way of his political attitudes and his championing of the working-classes, Burns was also an early pioneer of the Romantic movement that was to sweep Europe in the decades following his death, though he lived well before the term "Romantic" would carry such a connotation.

His influence on English and Scottish literature is far-reaching, and, along with William Wordsworth, Burns is perhaps one of the most enduringly popular and important poets of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. His status as a cultural icon is maintained through annual celebrations of his birthday in the form of Burns suppers.

Biography

Robert Burns, often abbreviated to simply Burns, and also known as Rabbie Burns, Robbie Burns, Scotland's favorite son, the Ploughman Poet, the Bard of Ayrshire, and in Scotland simply as The Bard, was born in Alloway, South Ayrshire, Scotland, the son of William Burns, a small farmer, and a man of considerable force of character. His youth was passed in poverty, hardship, and a degree of severe manual labor which left its traces in a premature stoop and weakened constitution. He had little regular schooling, and got much of what education he had from his father, who taught his children reading, writing, arithmetic, geography, and history, and also wrote for them A Manual of Christian Belief. He also received education from a tutor, John Murdock, who opened an "adventure school" in the Alloway parish in 1763 and taught both Robert and his brother Gilbert Latin, French, and mathematics. With all his ability and character, however, the elder Burns was consistently unfortunate, and migrated with his large family from farm to farm without ever being able to improve his circumstances.

In 1781 Burns went to Irvine to become a flax-dresser, but the unfortunate result of a little New Year carousing with fellow workmen, the shop was accidentally set ablaze and burned to the ground. This venture accordingly came to an end. In 1783 he started composing poetry in a traditional style using the Ayrshire dialect of Lowland Scots. In 1784 his father died. Burns and his brother Gilbert made an unsuccessful attempt to keep on the farm; failing that they removed to Mossgiel, where they maintained their uphill struggle for four years.

Poems, Chiefly in the Scottish Dialect

For the next few years Burns' life was nothing but hardship. In 1786, Burns fell in love with a woman named Jean Armour, but was devastated when her father refused to marry the couple, even though she was by that time pregnant with Burns' child. Enraged, Burns sought the hand of another woman, Mary Campbell, who promptly died. Distraught by these failures, and hounded by creditors to pay off the debts of his failing farm, Burns considered emigrating to Jamaica and abandoning the Scotland he had loved so long. Prior to making this decision, however, he decided to travel to the nearby town of Kilmarnock to publish a volume of the poems, under the plain title, Poems, Chiefly in the Scottish dialect. The edition contained much of his best work, including The Twa Dogs, Address to the Deil, Hallowe'en, The Cottar's Saturday Night, To a Mouse, and To a Mountain Daisy; many of which had been written at Mossgiel. The poems, as the title suggests, were written in a half-English/half-Scots dialect largely of Burns' own devising, and were selected specifically for the Edinburgh audience that Burns hoped to impress through his rural voice and natural imagery. An example of this unique style can be found in his beloved poem The Mouse from this volume:

- WEE, sleekit, cow’rin, tim’rous beastie,

- O, what a panic’s in thy breastie!

- Thou need na start awa sae hasty,

- Wi’ bickering brattle!

- I wad be laith to rin an’ chase thee,

- Wi’ murd’ring pattle!

- I’m truly sorry man’s dominion,

- Has broken nature’s social union,

- An’ justifies that ill opinion,

- Which makes thee startle

- At me, thy poor, earth-born companion,

- An’ fellow-mortal!

- I doubt na, whiles, but thou may thieve;

- What then? poor beastie, thou maun live!

- A daimen icker in a thrave

- ’S a sma’ request;

- I’ll get a blessin wi’ the lave,

- An’ never miss’t!

- Thy wee bit housie, too, in ruin!

- It’s silly wa’s the win’s are strewin!

- An’ naething, now, to big a new ane,

- O’ foggage green!

- An’ bleak December’s winds ensuin,

- Baith snell an’ keen!

- Thou saw the fields laid bare an’ waste,

- An’ weary winter comin fast,

- An’ cozie here, beneath the blast,

- Thou thought to dwell—

- Till crash! the cruel coulter past

- Out thro’ thy cell.

- That wee bit heap o’ leaves an’ stibble,

- Has cost thee mony a weary nibble!

- Now thou’s turn’d out, for a’ thy trouble,

- But house or hald,

- To thole the winter’s sleety dribble,

- An’ cranreuch cauld!

- But, Mousie, thou art no thy lane,

- In proving foresight may be vain;

- The best-laid schemes o’ mice an’ men

- Gang aft agley,

- An’lea’e us nought but grief an’ pain,

- For promis’d joy!

- Still thou art blest, compar’d wi’ me

- The present only toucheth thee:

- But, Och! I backward cast my e’e.

- On prospects drear!

- An’ forward, tho’ I canna see,

- I guess an’ fear!

The success of the work was immediate; the poet's name rang over all Scotland, and he was induced to go to Edinburgh to superintend the issue of a new edition. There he was received as an equal by the brilliant circle of men of letters which the city then boasted, and was a guest at aristocratic tables, where he bore himself with unaffected dignity. Here also Walter Scott, then a boy of 15, saw him and describes him as of "manners rustic, not clownish. His countenance … more massive than it looks in any of the portraits … a strong expression of shrewdness in his lineaments; the eye alone indicated the poetical character and temperament. It was large, and of a dark cast, and literally glowed when he spoke with feeling or interest." This visit resulted in some life-long friendships, and enough money for Burns to live relatively securely for the rest of his life.

The Scots Musical Museum

In the winter of 1786 in Edinburgh Burns met James Johnson, a struggling music engraver / music seller, with a love of old Scots songs and a determination to preserve them. Burns shared this interest and became an enthusiastic contributor to The Scots Musical Museum, a periodical collection of Scots songs. The first volume of this was published in 1787 and included three songs by Burns. He contributed 40 songs to Volume Two, and would end up responsible for about a third of the 600 songs in the whole collection, as well as making a considerable editorial contribution. The final volume was published in 1803. This publication would mark the beginning of the second phase of Burns' career, as a musicologist and songwriter, an occupation which occupied him for most of the remainder of his life.

On his return to Ayrshire Burns he renewed his relations with Jean Armour, whom he ultimately married, and took the farm of Ellisland near Dumfries. In the late 1780s he had taken lessons in the duties of an exciseman as a fallback should farming again prove unsuccessful. His popularity growing, at Ellisland his society was cultivated by the local gentry. His literary efforts and his duties in the Customs and Excise proved too much of a distraction to continue farming, a profession which in 1791 Burns gave up permanently.

Meanwhile, he was writing at his best, and in 1790 had produced Tam O' Shanter, one of his most beloved long poems. About this time he was offered and declined an appointment in London on the staff of the Star newspaper. He soon after also refused to become a candidate for a newly-created Chair of Agriculture in the University of Edinburgh, although influential friends offered to support his appointment.

Asked to furnish words for The Melodies of Scotland, another songbook with Scots lyrics, he responded by contributing over 100 songs. He also made major contributions to George Thomson's A Select Collection of Original Scottish Airs for the Voice. Arguably his claim to immortality chiefly rests on these volumes which placed him in the front rank of lyric poets, and were widely performed and published throughout the British Isles. Burns took a uniquely musical approach to composing his poems and songs of this period, insisting that he would begin with a tune and only when he had found a melody which pleased would he begin to find words to fit the line. His description of this process profoundly influenced the Romantic poets, particularly William Wordsworth, who would succeed in Burns' style:

My way is: I consider the poetic Sentiment, correspondent to my idea of the musical expression; then chuse my theme; begin one Stanza; when that is composed, which is generally the most difficult part of the business, I walk out, sit down now and then, look out for objects in Nature around me that are in unison or harmony with the cogitations of my fancy and workings of my bosom; humming every now and then the air with the verses I have framed. when I feel my Muse beginning to jade, I retire to the solitary fireside of my study, and there commit my effusions to paper; swinging, at intervals, on the hind-legs of my elbow chair, by way of calling forth my own critical strictures, as my, pen goes.

Following the publication of these numerous songs, Burns' worldly prospects were now perhaps better than they had ever been; but he was entering upon the last and darkest period of his career. He had become soured, and alienated many of his best friends by too freely expressing his sympathy with both the French Revolution and the then unpopular advocates of reform at home. His health began to give way; he became prematurely old, and fell into fits of despondency. He died on July 21, 1796, depressed at his inability to bring the revolutionary and democratic spirit home to his native Scotland. Within a short time of his death, money started pouring in from all over Scotland to support his widow and children.

His memory is celebrated by Burns clubs across the world; his birthday is an unofficial national day for Scots and those with Scottish ancestry, and his legacy persists as perhaps the single most important author in all of Scotland's storied history.

Burns' works and influence

Burns' direct influences in the use of Scots in poetry were Allan Ramsay and Robert Fergusson. Burns' poetry also drew upon a substantial familiarity and knowledge of the classics, the Bible, and English literature, as well as the Scottish tradition in which he was steeped. Burns was skilled in writing not only in the Scots language but also in the Scottish English dialect of the English language. Some of his works, such as Love and Liberty (also known as The Jolly Beggars), are written in both Scots and English for various effects.

Burns' themes included republicanism, Scottish patriotism, and class inequality. Burns and his works were a source of inspiration to the pioneers of liberalism, socialism and the campaign for Scottish self-government, and he is still widely respected by political activists today, ironically even by authoritarian nationalist figures because after his death Burns was appropriated into the fabric of Scotland's national identity. This, perhaps unique, ability to appeal to all strands of political opinion in the country resulted in his wide acclaim as the national poet of Scotland.

Burns' revolutionary views and occasionally radical ideas have led some to draw parallels between Burns and William Blake, but while they were contemporaries, based on the available evidence, it appears that they were unaware of each other, despite the fact that they were similar in temperament, attitude, and style. This similarity can be more likely attributed to the fact that they emerged from the same difficult circumstances during the same revolutionary times.

Burns is generally classified as a proto-Romantic poet, and he influenced William Wordsworth, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, and Percy Bysshe Shelley greatly. The Edinburgh literati worked to sentimentalize Burns during his life and after his death, dismissing his education by calling him a "heaven-taught ploughman." This insistence on Burns' lack of education is misleading, however; Burns himself played up his own ignorance and humble background to win over the wealthy readers of Edinburgh, but he was clearly not simply an ill-educated farmer who wrote verses on the back of his plough. His father, though poor, had driven the young Burns to read voraciously, and to underestimate his intellectual depth is to do Burns a great disservice. Later Scottish writers, especially Hugh MacDiarmid, fought to dismantle the sentimental Burns cult that had dominated Scottish literature, and thus eventually did away with the idolizing of Burns that Burns himself would have detested.

The genius of Burns is marked by spontaneity, directness, and sincerity, and his variety is marvelous, ranging from the tender intensity of some of his lyrics through the rollicking humor and blazing wit of Tam o' Shanter to the blistering satire of Holy Willie's Prayer and The Holy Fair. Burns fought at tremendous odds, and as Thomas Carlyle in his great essay claims, "Granted the ship comes into harbour with shrouds and tackle damaged, the pilot is blameworthy … but to know how blameworthy, tell us first whether his voyage has been round the Globe or only to Ramsgate and the Isle of Dogs." Burns, ramshackle though he may be, was a writer whose mind voyaged the world and extended far beyond even the grandest expectations.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Burns, Robert. The Canongate Burns: The Complete Poems and Songs of Robert Burns, ed. Andrew Noble and Patrick Scott Hogg. Edinburgh: Canongate, 2003. ISBN 1841953806

- Crawford, Robert. The Bard: Robert Burns, A Biography. Princeton University Press, 2009. ISBN 0691141711

- Thomson, George. A Select Collection of Original Scotish Airs for the Voice. Hansebooks, 2017. ISBN 3744796655

External links

All links retrieved December 14, 2022.

- Robert Burns Club based in Alexandria, Scotland

- Robert Burns Country: the 'official' Robert Burns site

- Robert Burns - Maybole Notable

- Poetry Archive: 128 poems of Robert Burns

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.