Rumba

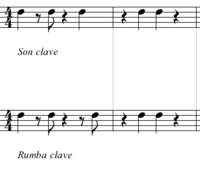

Rumba is both a family of music rhythms and a dance style that originated in Africa and traveled via the African slave trade to Cuba and the New World. The so-called rumba rhythm, a variation of the African standard pattern or clave rhythm, is the additive rhythmic grouping of an eight pulse bar (one 4/4 measure) into 3+3+2 or, less often, 3+5 (see van der Merwe 1989, p.321). Original Cuban rumba is highly polyrhythmic, and as such is often far more complex than the examples cited above. Yet, whether these rhythms range from simple to complex, they are excellent examples of the importance of a harmonious partnership wherein various rhythmic beats interplay with melodic sections while dance partners portray a mutual cooperation in the depiction of an exciting and romantic dance.

Ballroom Rumba and Rhumba

There are several social dances which can be subsumed under the rumba name: rumba itself (also spelled rhumba), bolero, based on Cuban rumba, and son. In American-style ballroom dancing, bolero is basically a slow version of the international-style back-and-forth (also known as slotted) rumba but without the hip or Cuban motion and with the added rise and fall motion.

There is the American ballroom rumba with the term "ballroom" as being understood in the more general meaning of that word. In the stricter sense, we speak of ballroom or Latin American dances as two different kinds of social or competitive dances in Europe. They are danced in either a box-step style (which in fact is called "Cuban Rumba" by dancing teachers) or a back and forth style with different hip motions supporting the movements. In Europe, only the latter form has survived (perhaps with the exception of the preliminary use for the very beginner). The "Rumba wars" of the ‘60s were between the French and British dancing teachers, who supported the two versions respectively.

Moreover, another variant of rumba music and dance was popularized in the United States in the 1930s, which was almost twice as fast, as exemplified by the popular tune, The Peanut Vendor. This type of "Big Band Rumba" was also known as Rhumba. The latter term still survives, with no clearly agreed upon meaning, and one may find it applied to Ballroom, Big Band, and Cuban rumbas.

Confusion about the style of rumba may arise if three essential facts are ignored. First is the speed of music, which has internationally decreased significantly since the fifties. Second, performing the dance requires attention from the teacher and does lead to very different-looking appearances on the floor. Third, figures are constantly wandering from one dance to another, because advanced dancers are usually searching for something new.

Characteristics

With the exception perhaps of the Paso Doble or stylized "bull fight," hardly any of the western social dances are as clearly defined as the Rumba. Journalists and teachers alike refer to the rumba as a "woman's dance" because it presents a female's body with arms, foot and leg lines very stylistically. The male also has an interesting dancing part in conjunction with his partner. These interactions demonstrate the emotions and the mutual dependency of soft rhythms and quick movements. The change of movements from being close together, to suddenly dancing away from the partner, create another name for the rumba or "Love Dance." The priority of movements is with the lady, which is called the "dance of seduction," where a stylized "love" is attempted to be portrayed but is not necessarily there.

Technique of the international rumba

The proper hip movements are most important to the dancers and not the rise and fall of the feet. "Slotted" dance means that the size of a step corresponds with the hip movement which precedes and supports it. A full description of one step might be the following: If you want to perform a back basic step, you must first "settle" the hip, allowing the right part of it to lower. Second, you rotate the left part of the hip to the right, left hip movement ending slightly back, whereby the hip is now in a diagonal position. Subsequently, this diagonal position is turned a quarter turn to the right while the right leg is led backward showing the knee. The weight is then transfered backward.

Figures

Basic figures or dance positions are comprised from the fundamental steps mentioned above. Such examples are the turn of the female partner out of a closed hold called the "New Yorker," and an opening of both partners to one side, holding each other only with one hand with bodies turning one quarter and feet three eighths, ending in the "Latin Cross" foot position, which is characteristic of the dance. There is also a figure called the "Hip Twist," where, by closing his feet following a backward movement, the hip movement of the man initiates a quarter turn of the lady to the right ending in the "Fan" position to then do a "Hockeystick" or "Alamana." In the "Natural Top" and "Reverse Top" figures or positions, the couple turns to the right or left while keeping a close hold, while in "Opening Out" the lady turns an extra quarter to the right. This movement is the opposite of the Fan, where she ends left. Dance sport competitors don’t usually use basic figures but a lot of choreography to impress adjudicators and spectators alike.

Note: There is a basic movement called "Cuban Break." The feet are in a split position staying in the same place and only the hip movements are made. A variant of this is called "Cuccaracha" with sideward steps without a full transfer of weight.

Technique and Music

International or competitive danced rumba is dancing on the counts of "2, 3, 4 and 1." Nowadays we speak of less than 30 bpm. Beginners can do a sideward step on one to come into the right movement. Beginning the Basic Movement on one is considered 'out of music' (at least in Europe). The Basic Step is beginning with a step with the left foot forward on count two for the man. However, due to the aforementioned hip movements, which take some time, the actual step or turn of a more advanced dancer—and corresponding lead—is danced between the two and three, on the half beat, or better still, almost before the next beat. This makes the turn faster and therefore looks more exciting. There are moments of silence which help to alternate the look of the sequence of figures. In a still more elaborate approach of combining music and dance, the dancers also may consider longer cohesive parts of the music "phrases" or "additive rhythms" as significant and may execute figures or poses corresponding to the music instead of just doing the "routine" movements. In general, the theme of the dance should be preserved and the rumba should not be aerobic or acrobatic.

Gypsy Rumba

In the 1990s, the French group called the Gypsy Kings of Spanish descent became a popular "New Flamenco" group by performing the Rumba Flamenca (or the rumba gitana or Catalan rumba).

Cuban Rumba

Rumba arose in Havana in the 1890s. As a sexually charged Afro-Cuban dance, rumba was often suppressed and restricted because it was viewed as dangerous and lewd.

Later, Prohibition in the United States caused a flourishing of the relatively tolerated cabaret rumba, as American tourists flocked to see unsophisticated sainetes or short plays which many times featured rumba dancing.

There seems to exist an historical habit of American and British dancing teachers to "castrate" or tone down particularly erotic or wild dances. In comparison, the Black Americans' Lindy Hop of the ‘20s was transformed into the ‘30s Jitterbug, and the wild Jitterbug of the ‘40s mutated into Jive. The Rock ´n´Roll of the ‘50s died out in the United States and was transformed in Central Europe to a kind of precursor of a powerful aerobic dancing with complicated acrobatics, and then into a dance form called the Boogie-Woogie, which resembles the old ‘50s Rock`n`Roll.

Therefore, dancing teachers were "mainstreaming" and consequently better propagating the revised dances to a cosmopolitan clientele. Thus, important movements and figures of the original rumba were eliminated in the American social dance environment. That was not unwise considering the unwillingness shown by many dancers in performing extreme hip-movements. Yet in recent years, teachers have begun stylizing their instruction as "authentic cuban" and thus a valuable kind of instruction.

Cuban music

Perhaps because of the mainstream and middle-class avoidance for the true rumba, danzón and "son montuno," these dance forms became seen as "the" national music for Cuba, and the expression of "Cubanismo." Rumberos reacted by mixing the two genres in the 1930s, ‘40s and ‘50s, and by the mid-‘40s, the genre had regained much respect, especially the "guaguanco" style.

Rumba and some relatives

The rumba is sometimes confused with the "salsa" dance although they share the same origins. For example, they share the four beats on one basic step and the character of that step, but few other movements are the same. The hip movements of the Salsa is different due to the faster music. In the United States, the salsa is often danced without much hip-movement as well as in the case of the rumba.

There are several rhythms of the Rumba family, and associated styles of dance:

- Yambú (slow; the dance often involving mimicking old men and women walking bent)

- Guaguancó (medium-fast, often flirtatious, involving pelvic thrusts by the male dancers, the vacunao)

- Columbia (fast, aggressive and competitive, generally danced by men only, occasionally mimicking combat or dancing with knives)

- Columbia del Monte (very fast)

All of these share the instrumentation of three conga drums or cajones, claves, palitos and/or the guagua, lead singer and coro, optionally, the "chekeré" and cowbells. The heavy polyrhythms magnify the importance of the clave instrument.

African Rumba

Rumba, like salsa and some other Caribbean and South American sounds have their rhythmic roots to varying degrees in African musical traditions, having been brought there by African slaves. In the late 1930s and early 1940s in the Congo, especially in Leopoldville (later renamed Kinshasa), musicians developed a music known as rumba, based largely upon Cuban rhythms. Due to an expanding market, Cuban music was becoming widely available throughout Africa and even Miriam Makeba had her start in singing for a group called "The Cuban Brothers." Musicians in the Congo, perhaps recognizing the strong Congolese influence present in Afro-Cuban music were especially fond of the new Cuban sound.

This brand of African rumba became popular in Africa in the 1950s. Some of the most notable bands were Franco Luambo's "OK Jazz" and Grand Kalle's "African Jazz." These bands spawned well known rumba artists such as Sam Mangwana, Dr. Nico Kasanda, and Tabu Ley Rochereau, who pioneered "Soukous," the genre into which African rumba evolved in the 1960s. Soukous is still sometimes referred to as rumba.

George Gerswhin wrote an overture for orchestra featuring the rumba and originally titled "Rumba" . The name of the work was eventually changed to the "Cuban Overture" .

Rumba rhythm

The rhythm which is known now as "rumba rhythm" was popular in European music beginning in the 1500s until the later Baroque, with classical era composers preferring syncopation such as 3+2+3. It reappeared in the nineteenth century.

Conclusion

The rumba has evolved a long way from its simple beginnings as a West Indian folk dance demonstrating the aggressions and submissions depicted by the dancing partners while expressing the emotions of love. So exciting were the accompanying rhythmic staccato beats that the rhythm and melodies were also known as rumba music. The music and dancing were created to co-exist in a most harmonious and fulfilling manner.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Daniel, Yvonne. Rumba: dance and social change in contemporary Cuba. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1995. ISBN 0-253-31605-7

- Manuel, Peter Lamarche, Kenneth M. Bilby, and Michael D. Largey. Caribbean currents: Caribbean music from rumba to reggae. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1995. ISBN 1-566-39338-8

- Steward, Sue. Musica!: salsa, rumba, merengue, and more: the rhythm of Latin America. San Francisco: Chronicle Books, 1999. ISBN 0-811-82566-3

- van der Merwe, Peter. Origins of the Popular Style: The Antecedents of Twentieth-Century Popular Music. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1989. ISBN 0-19-316121-4

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.