| Russian Revolution of 1905 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Demonstrations before Bloody Sunday | |||||||

| |||||||

| Combatants | |||||||

Supported by:

|

Supported by:

| ||||||

| Commanders | |||||||

| Casualties | |||||||

| 3,611 killed or wounded[1] | 15,000 killed[1] 20,000 wounded[1] 38,000 captured[1] 1 battleship surrendered to Romania | ||||||

The Russian Revolution of 1905 began as a wave of mass political and social unrest that spread through vast areas of the Russian Empire. The autocracy faced increasing challenges as it struggled to adapt to the changing environment. Socioeconomic changes brought about by the transition from a rural agrarian economy of landholders and peasants to a modern industrialized society proved problematic for the political system. Attempts at reforms by former Prime Minister Sergei Witte were modestly successful but wholly inadequate. The unrest was exacerbated by the disastrous Russian defeat in the Russo-Japanese war (1904–1905). In the face of these challenges, a protest march to the Winter Palace, led by an Orthodox priest, triggered mass protests when it was met with deadly force. As many as 200 protesters were killed (official counts were lower). The events of the massacre, known as Bloody Sunday, led to worker strikes, peasant unrest, and finally military mutinies.

By the end of 1905, the revolution resulted in a number of reforms that allowed Tsar Nicholas to maintain his hold on power. Constitutional reform (in the form of the "October Manifesto"), included the establishment of the State Duma, the multi-party system, and finally a change to the fundamental law established by Mikhail Speransky in 1833 with the adoption of the Russian Constitution of 1906.

The 1905 revolution is generally understood to have set the stage for the 1917 revolutions that enabled the Bolsheviks to emerge as a distinct political movement in Russia.

Causes

The immediate causes of the revolution lay in four problems in Russian society. Newly emancipated peasants earned too little and were not allowed to sell or mortgage their allotted land. Ethnic and national minorities resented the government because of its "Russification" of the Empire. Russia practiced discrimination and repression against national minorities, such as banning them from voting; serving in the Imperial Guard or Navy; and limiting their attendance in schools. A nascent industrial working class resented the government for doing too little to protect them, as it banned strikes and the organization of labor unions. Finally, university students developed a new consciousness after discipline was relaxed in the institutions, and they were fascinated by increasingly radical ideas. Taken individually, these issues might not have affected the course of Russian history, but together they created the conditions for a potential revolution.[2]

At the turn of the century, discontent with the Tsar’s dictatorship was manifested not only through the growth of political parties dedicated to the overthrow of the monarchy but also through industrial strikes for better wages and working conditions, protests and riots among peasants, university demonstrations, and the assassination of government officials, often done by Socialist Revolutionaries.[3]

Because the Russian economy was tied to European finances, the contraction of Western money markets in 1899–1900 plunged Russian industry into a deep and prolonged crisis; it outlasted the dip in European industrial production. This setback aggravated social unrest during the five years preceding the revolution of 1905.[4]

The government finally recognized these problems, albeit in a shortsighted and narrow-minded way. Minister of Interior Vyacheslav von Plehve commented in 1903 that, after the agrarian problem, the most serious issues plaguing the country were those of the Jews, the schools, and the workers, in that order.[5]

Beneath these immediate causes lay a country that was ill-prepared for the changes brought about by the Industrial Revolution and the influence of modern socioeconomic systems and structures. From the time of Alexander Radishchev until the early twentieth century, Russia had struggled to modernize its political institutions under imperial rule that was becoming increasingly anachronistic.

Structural Problems

Breakdown of Feudal system

Under stress from the pressures of modernity, the old Russian feudal system began to show serious strains. Every year, thousands of nobles in debt mortgaged their estates to the noble land bank or sold them to municipalities, merchants, or peasants. By the time of the revolution, the nobility had sold off one-third of its land and mortgaged another third. The peasants had been freed by the Emancipation reform of 1861, but their lives were generally quite limited. The government hoped to develop the peasants as a politically conservative, land-holding class by enacting laws to enable them to buy land from nobility, by paying small installments over many decades.[6]

Such land, known as "allotment land," would not be owned by individual peasants, but by the peasant commune; individual peasants would have rights to strips of land to be assigned to them under the open field system. A peasant could not sell or mortgage this land, so in practice he could not renounce his rights to his land, and he would be required to pay his share of redemption dues to the village commune. This plan was intended to prevent peasants from becoming part of the proletariat. However, the peasants were not given enough land to provide for their needs:

Their earnings were often so small that they could neither buy the food they needed nor keep up the payment of taxes and redemption dues they owed the government for their land allotments. By 1903 their total arrears in payments of taxes and dues was 118 million rubles.[7]

The situation worsened, as masses of hungry peasants roamed the countryside looking for work, sometimes walked hundreds of kilometers to find it. Desperate peasants proved capable of violence:

In the provinces of Kharkov and Poltava in 1902, thousands of them, ignoring restraints and authority, burst out in a rebellious fury that led to extensive destruction of property and looting of noble homes before troops could be brought to subdue and punish them.[7]

These violent outbreaks caught the attention of the government, so it created many committees to investigate the causes. The committees concluded that no part of the countryside was prosperous; some parts, especially the fertile areas known as "black-soil region," were in decline. Although cultivated acreage had increased in the last half century, the increase had not been proportionate to the growth of peasant populations, which had doubled. "There was general agreement at the turn of the century that Russia faced a grave and intensifying agrarian crisis due mainly to rural overpopulation with an annual excess of fifteen to eighteen live births over deaths per 1,000 inhabitants."[8] The investigations revealed many difficulties but the committees could not find solutions that were both sensible and "acceptable" to the government.[5]

Nationality problem

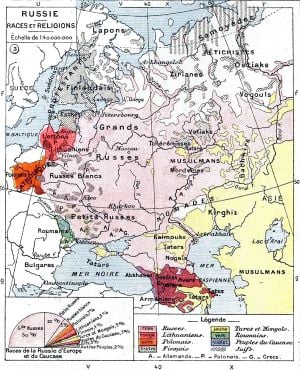

Russia was a multi-ethnic empire. Nineteenth-century Russians saw cultures and religions in a clear hierarchy. Non-Russian cultures were tolerated in the empire but were not necessarily respected. "European civilization was valued over Asian culture, and Christianity was on the whole considered more progressive and 'true' than other religions."[9]

For generations, Russian Jews had been considered a special problem. Jews constituted only about 4 percent of the population, but were concentrated in the western borderlands.[10] Like other minorities in Russia, the Jews lived "miserable and circumscribed lives, forbidden to settle or acquire land outside the cities and towns, legally limited in attendance at secondary school and higher schools, virtually barred from legal professions, denied the right to vote for municipal councilors, and excluded from services in the Navy or the Guards."[5]

The government's treatment of Jews, although considered its own issue, was similar to its policies in dealing with all national and religious minorities. "Russian administrators, who never succeeded in coming up with a legal definition of 'Pole', despite the decades of restrictions on that ethnic group, regularly spoke of individuals 'of Polish descent' or, alternatively, 'of Russian descent', making identity a function of birth."[11] This policy only succeeded in producing or aggravating feelings of disloyalty. There was growing impatience with their inferior status and resentment against "Russification,"[5] the cultural assimilation definable as "a process culminating in the disappearance of a given group as a recognisably distinct element within a larger society".[12]

Besides the imposition of a uniform Russian culture throughout the empire, the government's pursuit of Russification, especially during the second half of the nineteenth century, had political motives. After finally agreeing to emancipate the serfs in 1861, demands for greater freedoms continued to ramp up.

In the modern world, the Russian state was forced to account for public opinion, but the government failed to gain the public's support. Russification was an attempt to secure the support of Russians.[13] Another motive for Russification policies was the Polish uprising of 1863. Unlike other minority nationalities, the Poles, in the eyes of the Tsar, were a direct threat to the empire's stability. After the rebellion was crushed, the government implemented policies to reduce Polish cultural influences. In the 1870s the government began to distrust German elements on the western border. The Russian government felt that the Unification of Germany would upset the power balance among the great powers of Europe and that Germany would use its strength against Russia. The government thought that the borders would be defended better if the borderland were more "Russian" in character.[14] Russia was a large, multi-ethnic country, but this became a growing problem that plagued the Russian government in the years leading up to the revolution.

Labor problem

The economic situation in Russia before the revolution presented a grim picture. The government had experimented with laissez-faire capitalist policies, but this strategy largely failed to gain traction within the Russian economy until the 1890s. Meanwhile, "agricultural productivity stagnated, while international prices for grain dropped, and Russia’s foreign debt and need for imports grew. War and military preparations continued to consume government revenues. At the same time, the peasant taxpayers' ability to pay was strained to the utmost, leading to widespread famine in 1891."[15]

In the 1890s, under Finance Minister Sergei Witte, a crash governmental program was proposed to promote industrialization. His policies included heavy government expenditures for railroad building and operations, subsidies and supporting services for private industrialists, high protective tariffs for Russian industries (especially heavy industry), an increase in exports, currency stabilization, and encouragement of foreign investments.[16] His plan was largely successful and during the 1890s. "Russian industrial growth averaged 8 percent per year. Railroad mileage grew from a very substantial base by 40 percent between 1892 and 1902."[16]

Unfortunately, Witte's success in implementing this program helped spur the 1905 revolution and eventually the February Revolution and October Revolutions of 1917 because it exacerbated social tensions. "Besides dangerously concentrating a proletariat, a professional and a rebellious student body in centers of political power, industrialization infuriated both these new forces and the traditional rural classes."[17] The government policy of financing industrialization through taxing peasants forced millions of peasants to work in towns. The "peasant worker" saw his labor in the factory as the means to consolidate his family's economic position in the village and played a role in determining the social consciousness of the urban proletariat. The new concentrations and flows of peasants spread urban ideas to the countryside, breaking down the isolation of peasants on communes.[18]

Industrial workers began to feel dissatisfaction with the Tsarist government despite the protective labor laws the government decreed. Some of those laws included the prohibition of children under 12 from working, with the exception of night work in glass factories. Employment of children aged 12 to 15 was prohibited on Sundays and holidays. Workers had to be paid in cash at least once a month, and limits were placed on the size and bases of fines for workers who were tardy. Employers were prohibited from charging workers for the cost of lighting of the shops and plants.[5] Despite these labor protections, the workers believed that the laws were not enough to free them from unfair and inhumane practices. At the start of the twentieth century, Russian industrial workers worked on average an 11-hour day (10 hours on Saturday), factory conditions were perceived as grueling and often unsafe, and attempts at independent unions were often not accepted. Many workers were forced to work beyond the maximum of 11 and a half hours per day. Others were still subject to arbitrary and excessive fines for tardiness, mistakes in their work, or absence. Russian industrial workers were also the lowest-wage workers in Europe. Although the cost of living in Russia was low, "the average worker's 16 rubles per month could not buy the equal of what the French worker's 110 francs would buy for him." Furthermore, the same labor laws prohibited organization of trade unions and strikes. Dissatisfaction turned into despair for many impoverished workers, which made them more sympathetic to radical ideas.[19] These discontented, radicalized workers became key to the revolution by participating in illegal strikes and revolutionary protests.

The Educated class problem

The Minister of the Interior, Vyacheslav von Plehve, designated schools as a pressing problem for the government, but he did not realize it was only a symptom of anti=government feelings among the educated class. Students of universities, other schools of higher learning, and occasionally of secondary schools and theological seminaries were part of this group.[20]

Student radicalism began around the time Tsar Alexander II came to power. Alexander abolished serfdom and enacted fundamental reforms in the legal and administrative structure of the Russian empire, which were revolutionary for their time.[21] He lifted many restrictions on universities and abolished obligatory uniforms and military discipline. This ushered in a new freedom in the content and reading lists of academic courses. In turn, that created student subcultures, as youth were willing to live in poverty in order to receive an education. As universities expanded, there was a rapid growth of newspapers, journals, and an organization of public lectures and professional societies. The 1860s was a time when the emergence of a new public sphere was created in social life and professional groups. This created the idea of their right to have an independent opinion.[22]

The government was alarmed by these communities, and in 1861 tightened restrictions on admission and prohibited student organizations; these restrictions resulted in the first ever student demonstration, held in St. Petersburg, which led to a two-year closure of the university.[22] The consequent conflict with the state was an important factor in the chronic student protests over subsequent decades. The atmosphere of the early 1860s gave rise to political engagement by students outside universities that became a tenet of student radicalism by the 1870s. Student radicals described "the special duty and mission of the student as such to spread the new word of liberty. Students were called upon to extend their freedoms into society, to repay the privilege of learning by serving the people, and to become in Nikolai Ogarev's phrase 'apostles of knowledge'."[23] During the next two decades, universities produced a significant share of Russia's revolutionaries. Prosecution records from the 1860s and 1870s show that more than half of all political offences were committed by students despite being a minute proportion of the population. "The tactics of the left-wing students proved to be remarkably effective, far beyond anyone's dreams. Sensing that neither the university administrations nor the government any longer possessed the will or authority to enforce regulations, radicals simply went ahead with their plans to turn the schools into centres of political activity for students and non-students alike."[24]

Rise of the opposition

The events of 1905 were preceded by a Progressive and academic agitation for more political democracy and limits to Tsarist rule in Russia, and an increase in strikes by workers against employers for radical economic demands and union recognition, (especially in southern Russia). Many socialists view this as a period when the rising revolutionary movement was met with rising reactionary movements. As Rosa Luxemburg stated in The Mass Strike, when collective strike activity was met with what is perceived as repression from an autocratic state, economic and political demands grew into and reinforced each other.[25]

Russian progressives formed the Union of Zemstvo Constitutionalists in 1903 and the Union of Liberation in 1904, which called for a constitutional monarchy. Russian socialists formed two major groups: the Socialist Revolutionary Party, following the Russian populist tradition, and the Marxist Russian Social Democratic Labor Party.

In the autumn of 1904, liberals started a series of banquets, nominally celebrating the 40th anniversary of the liberal court statutes, but actually an attempt to circumvent laws against political gatherings (modeled on the campagne des banquets leading up to the French Revolution of 1848). The banquets resulted in calls for political reforms and a constitution. On 13 December [O.S. 30 November] 1904, the Moscow City Duma passed a resolution demanding establishment of an elected national legislature, full freedom of the press, and freedom of religion. Similar resolutions and appeals from other city dumas and zemstvo councils followed.

Tsar Nicholas II made a move to fulfill many of these demands, appointing liberal Pyotr Dmitrievich Sviatopolk-Mirsky Minister of the Interior after the assassination of Vyacheslav von Plehve. On 25 December [O.S. 12 December] 1904, the Tsar issued a manifesto promising the broadening of the Zemstvo and more authority local municipal councils, insurance for industrial workers, the emancipation of Inorodtsy (non-Russians) and abolition of censorship. The crucial demand of representative national legislature was missing in the manifesto.

Worker strikes in Caucasus broke out in March 1902 and strikes on the railway originating from pay disputes took on other issues and drew in other industries, culminating in a general strike at Rostov-on-Don in November. Daily meetings of 15,000 to 20,000 heard openly revolutionary appeals for the first time, before a massacre defeated the strikes. But reaction to the massacres brought political demands to purely economic ones. Luxemburg described the situation in 1903 by saying: "the whole of South Russia in May, June and July was aflame,"[26] including Baku where separate wage struggles culminated in a citywide general strike, and Tiflis, where commercial workers gained a reduction in the working day. They were joined by factory workers. In 1904, massive strike waves broke out in Odessa in the spring, Kiev in July, and Baku in December. This all set the stage for the strikes in St. Petersburg in December 1904 to January 1905 seen as the first step in the 1905 revolution.

| Years | Average annual strikes[27] |

|---|---|

| 1862–69 | 6 |

| 1870–84 | 20 |

| 1885–94 | 33 |

| 1895–1905 | 176 |

Start of the revolution

In December 1904, a strike occurred at the Putilov plant (a railway and artillery supplier) in St. Petersburg. Sympathy strikes in other parts of the city raised the number of strikers to 150,000 workers in 382 factories.[28] By 21 January [O.S. 8 January] 1905, the city had no electricity and newspaper distribution was halted. All public areas were declared closed.

Bloody Sunday

The autocracy had been under-girded by the veneration of the masses, especially the peasantry, but in 1905 an event occurred that would all but destroy that support. The autocracy was struggling to manage growing expectations of greater democracy and economic reform when it made a terrible misstep.

On January 22, 1905 controversial Orthodox priest Georgy Gapon, who headed a police-sponsored workers' association, led a huge workers' procession to the Winter Palace to deliver a petition[29] to the Tsar on Sunday, 22 January [O.S. 9 January] 1905. The troops guarding the Palace were ordered to tell the demonstrators not to pass a certain point, according to Sergei Witte, and at some point, troops opened fire on the demonstrators, causing between 200 (according to Witte) and 1,000 deaths. Official government numbers were 96 dead and 333 injured, but actual numbers are likely much higher. The event became known as Bloody Sunday, and is considered by many scholars as the start of the active phase of the revolution. Strikes erupted all over Russia in response to the massacre. The most important result it that is undermined loyalty to the Tsar among his constituencies.

The events in St. Petersburg provoked public indignation and a series of massive strikes that spread quickly throughout the industrial centers of the Russian Empire. Polish socialists—both the PPS and the SDKPiL—called for a general strike. By the end of January 1905, over 400,000 workers in Russian Poland were on strike (see Revolution in the Kingdom of Poland (1905–1907)). Half of European Russia's industrial workers went on strike in 1905, and 93.2% in Poland.[30] There were also strikes in Finland and the Baltic coast. In Riga, 130 protesters were killed on 26 January [O.S. 13 January] 1905, and in Warsaw a few days later over 100 strikers were shot on the streets. By February, there were strikes in the Caucasus, and by April, in the Urals and beyond. In March, all higher academic institutions were forcibly closed for the remainder of the year, adding radical students to the striking workers. A strike by railway workers on 21 October [O.S. 8 October] 1905 quickly developed into a general strike in Saint Petersburg and Moscow. This prompted the setting up of the short-lived Saint Petersburg Soviet of Workers' Delegates, an admixture of Bolsheviks and Mensheviks headed by Khrustalev-Nossar and despite the Iskra split would see the likes of Julius Martov and Georgi Plekhanov spar with Lenin. Leon Trotsky, who felt a strong connection to the Bolsheviks, had not given up a compromise but spearheaded strike action in over 200 factories.[31] By 26 October [O.S. 13 October] 1905, over 2 million workers were on strike and there were almost no active railways in all of Russia. Growing inter-ethnic confrontation throughout the Caucasus resulted in Armenian–Tatar massacres, heavily damaging the cities and the Baku oilfields.

At the same time the government was pursuing an unsuccessful and bloody war with Japan. The Russo-Japanese War (1904–1905) caused unrest in army reserve units. On January 2, 1905, Port Arthur was lost; in February 1905, the Russian army was defeated at Mukden, losing almost 80,000 men. On May 27-28, 1905, the Russian Baltic Fleet was defeated at Tsushima. Witte was dispatched to make peace, negotiating the Treaty of Portsmouth (signed 5 September [O.S. 23 August] 1905). In 1905, there were naval mutinies at Sevastopol (see Sevastopol Uprising), Vladivostok, and Kronstadt, peaking in June with the mutiny aboard the battleship Potemkin. The mutineers eventually surrendered the battleship to Romanian authorities on July 8th in exchange for asylum, then the Romanians returned her to Imperial Russian authorities on the following day. Some sources claim over 2,000 sailors died in the suppression.[32] The mutinies were disorganized and quickly crushed. Despite these mutinies, the armed forces were largely apolitical and remained mostly loyal, if dissatisfied—and were widely used by the government to control the 1905 unrest.

Nationalist groups had been angered by the Russification undertaken since Alexander II. The Poles, Finns, and the Baltic provinces all sought autonomy, and also freedom to use their national languages and promote their own culture.[33] Muslim groups were also active, founding the Union of the Muslims of Russia in August 1905. Certain groups took the opportunity to settle differences with each other rather than the government. Some nationalists undertook anti-Jewish pogroms, possibly with government aid, and in total over 3,000 Jews were killed.[34]

The number of prisoners throughout the Russian Empire, which had peaked at 116,376 in 1893, fell by over a third to a record low of 75,009 in January 1905, chiefly because of several mass amnesties granted by the Tsar.[35] Wheatcroft speculates about the role the amnestied criminals played.

Government response

On January 12, the Tsar appointed Dmitri Feodorovich Trepov as governor in St Petersburg and dismissed the Minister of the Interior, Pyotr Sviatopolk-Mirskii, on 18 February [O.S. 5 February] 1905. He appointed a government commission to research the cause of the workers' discontent in and around St. Petersburg that resulted in the strikes. The commission was headed by Senator NV Shidlovsky, a member of the State Council, and included officials, chiefs of government factories, and private factory owners. It was also meant to have included workers' delegates elected according to a two-stage system. Elections of the workers delegates were, however, blocked by the socialists who wanted to divert the workers from the elections to the armed struggle. On 5 March [O.S. 20 February] 1905, the Commission was dissolved without having started work. Following the assassination of his uncle, the Grand Duke Sergei Aleksandrovich, on 17 February [O.S. 4 February] 1905, the Tsar made new concessions. On 2 March [O.S. 18 February] 1905 he published the Bulygin Rescript, which promised the formation of a consultative assembly, religious tolerance, freedom of speech (in the form of language rights for the Polish minority) and a reduction in the peasants' redemption payments. On 24 and 25 May [O.S. 11 and 12 May] 1905, about 300 Zemstvo and municipal representatives held three meetings in Moscow, which passed a resolution, asking for popular representation at the national level. On 6 June [O.S. 24 May] 1905, Nicholas II had received a Zemstvo deputation. Responding to speeches by the deputies, the Tsar confirmed his promise to convene an assembly of people's representatives.

Height of the Revolution

Tsar Nicholas II agreed on 2 March [O.S. 18 February] to the creation of a State Duma of the Russian Empire but with consultative powers only. When its slight powers and limits on the electorate were revealed, unrest redoubled. The Saint Petersburg Soviet was formed and called for a general strike in October, refusal to pay taxes, and the withdrawal of bank deposits.

In June and July 1905, there were many peasant uprisings in which peasants seized land and tools. Disturbances in the Russian-controlled Congress Poland culminated in June 1905 in the Łódź insurrection. Surprisingly, only one landlord was recorded as killed.[36] Far more violence was inflicted on peasants outside the commune: 50 deaths were recorded.

The October Manifesto, written by Sergei Witte and Alexis Obolenskii, was presented to the Tsar on 14 October [O.S. 1 October] . It closely followed the demands of the Zemstvo Congress in September, granting basic civil rights, allowing the formation of political parties, extending the franchise towards universal suffrage, and establishing the Duma as the central legislative body. The Tsar waited and argued for three days, but finally signed the manifesto on 30 October [O.S. 17 October] 1905, citing his desire to avoid a massacre and his realization that there was insufficient military force available to pursue alternative options. He regretted signing the document, saying that he felt "sick with shame at this betrayal of the dynasty ... the betrayal was complete."

When the manifesto was proclaimed, there were spontaneous demonstrations of support in all the major cities. The strikes in Saint Petersburg and elsewhere officially ended or quickly collapsed. A political amnesty was also offered. The concessions came hand-in-hand with renewed, and brutal, action against the unrest. There was also a backlash from the conservative elements of society, with right-wing attacks on strikers, left-wingers, and Jews.

While the Russian liberals were satisfied by the October Manifesto and prepared for upcoming Duma elections, radical socialists and revolutionaries denounced the elections and called for an armed uprising to destroy the Empire.

Some of the November uprising of 1905 in Sevastopol, headed by retired naval Lieutenant Pyotr Schmidt, was directed against the government, while some was undirected. It included terrorism, worker strikes, peasant unrest and military mutinies, and was only suppressed after a fierce battle. The Trans-Baikal railroad fell into the hands of striker committees and demobilized soldiers returning from Manchuria after the Russo–Japanese War. The Tsar had to send a special detachment of loyal troops along the Trans-Siberian Railway to restore order.

Between 5 and 7 December [O.S. 22 and 24 November] , there was a general strike by Russian workers. The government sent troops on December 7, and a bitter street-by-street fight began. A week later, the Semyonovsky Regiment was deployed, and used artillery to break up demonstrations and to shell workers' districts. On 18 December [O.S. 5 December] , with around a thousand people dead and parts of the city in ruins, the workers surrendered. After a final spasm in Moscow, the uprisings ended in December 1905. According to figures presented in the Duma by Professor Maksim Kovalevsky, by April 1906 more than 14,000 people had been executed and 75,000 imprisoned.[37] Historian Brian Taylor states the number of deaths in the 1905 Revolution was in the "thousands", and notes one source that puts the figure at over 13,000 deaths.[38]

Repression

The years of revolution were marked by a dramatic rise in the numbers of death sentences and executions. Different figures on the number of executions were compared by Senator Nikolai Tagantsev,[39] and are listed in the table.

| Year | Number of executions by different accounts | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Report by Ministry of Internal Affairs Police Department to the State Duma on 19 February [O.S. 6 February] 1909 | Report by Ministry of War Military Justice department | By Oscar Gruzenberg | Report by Mikhail Borovitinov, assistant head of Ministry of Justice Chief Prison Administration, at the International Prison Congress in Washington, 1910. | |

| 1905 | 10 | 19 | 26 | 20 |

| 1906 | 144 | 236 | 225 | 144 |

| 1907 | 456 | 627 | 624 | 1,139 |

| 1908 | 825 | 1,330 | 1,349 | 825 |

| Total | 1,435 + 683[40] = 2,118 | 2,212 | 2,235 | 2,628 |

| Year | Number of executions |

|---|---|

| 1909 | 537 |

| 1910 | 129 |

| 1911 | 352 |

| 1912 | 123 |

| 1913 | 25 |

These numbers reflect only executions of civilians,[41] and do not include a large number of summary executions by punitive army detachments and executions of military mutineers. Peter Kropotkin, an anarchist, noted that official statistics excluded executions conducted during punitive expeditions, especially in Siberia, Caucasus and the Baltic provinces. By 1906 some 4,509 political prisoners were incarcerated in Russian Poland, 20 percent of the empire's total.[42]

October Manifesto

Even after Bloody Sunday and defeat in the Russo-Japanese War, Nicholas II had been slow to offer a meaningful solution to the social and political crisis. At this point, he became more concerned with his personal affairs such as the illness of his son, whose struggle with haemophilia was overseen by Rasputin. Nicholas also refused to believe that the population was demanding changes in the autocratic regime, seeing "public opinion" as mainly the "intelligentsia" and believing himself to be the patronly "father figure" to the Russian people. Sergei Witte, the minister of Russia, frustratingly argued with the Tsar that an immediate implementation of reforms was needed to retain order in the country. It was only after the Revolution started picking up steam that Nicholas was forced to make concessions laid out in the October Manifesto.

Issued on October 17, 1905, the Manifesto stated that the government would grant the population reforms such as the right to vote and to convene in assemblies. Its main provisions were:

- The granting of the population "inviolable personal rights" including freedom of conscience, speech, and assemblage

- Giving the population who were previously cut off from doing so participation in the newly formed Duma

- Ensuring that no law would be passed without the consent of the Imperial Duma.[43]

The immediate impact was the Days of Freedom, a six-week period from October 17 to early December. This period witnessed an unprecedented level of freedom on all publications—revolutionary papers, brochures, etc.—even though the Tsar officially retained the power to censor provocative material. This opportunity allowed the press to address the Tsar, and government officials, in a harsh, critical previously unheard of tone. The freedom of speech also opened the floodgates for meetings and organized political parties. In Moscow alone, over 400 meetings took place in the first four weeks. Some of the political parties that came out of these meetings were the Constitutional Democrats (Kadets), Social Democrats, Socialist Revolutionaries, Octobrists, and the far-rightist Union of Russian People.

Among all the groups that benefited most from the Days of Freedom were the labor unions. In fact, the Days of Freedom witnessed unionization in the history of the Russian Empire at its apex. At least 67 unions were established in Moscow, as well as 58 in St. Petersburg; the majority of both combined were formed in November 1905 alone. For the Soviets, it was a watershed period of time: nearly 50 of the unions in St. Petersburg came under Soviet control, while in Moscow, the Soviets had around 80,000 members. This large sector of power allowed the Soviets enough clout to form their own militias. In St. Petersburg alone, the Soviets claimed around 6,000 armed members with the purpose of protecting the meetings.[44]

Perhaps empowered in their newfound window of opportunity, the St. Petersburg Soviets, along with other socialist parties, called for armed struggles against the Tsarist government. The writers of the October Manifesto were caught off guard by the surge in revolts. One of the main reasons for writing the October Manifesto centered on the government's "fear of the revolutionary movement."[45] In fact, many officials believed this fear was practically the sole reason for the Manifesto's creation in the first place. Among those more scared was Dmitri Feodorovich Trepov, governor general of St. Petersburg and deputy minister of the interior. Trepov urged Nicholas II to stick to the principles in the Manifesto, for "every retreat ... would be hazardous to the dynasty."[46]

Creation of Duma and Stolypin

There had been earlier attempts in establishing a Russian Duma before the October Manifesto, but these attempts faced dogged resistance and propositions for restrictions to the Duma's legislative powers remained persistent. A decree on February 20, 1906 transformed the State Council, the advisory body, into a second chamber with legislative powers "equal to those of the Duma."[47] Not only did this transformation violate the Manifesto, but the Council became a buffer zone between the Tsar and Duma, slowing whatever progress the latter could achieve. Even three days before the Duma's first session, on April 24, 1906, the Fundamental Laws further limited the assembly's movement by giving the Tsar the sole power to appoint/dismiss ministers.[48] Worse, the Tsar alone had control over many facets of political reins—all without the Duma's expressed permission. The unsuspecting Duma assembly convened in April 27, but it quickly found itself unable to do much without violating the Fundamental Laws. Defeated and frustrated, the majority of the assembly voted no confidence and handed in their resignations little more than two weeks later on May 13.[49]

The attacks on the Duma were not confined to its legislative powers. By the time the Duma opened, it was missing crucial support from its populace, thanks in no small part to the government's return to Pre-Manifesto levels of suppression. The Soviets were forced to lay low for a long time, while the zemstvos turned against the Duma when the issue of land appropriation came up. The issue of land appropriation was the most contentious of the Duma's appeals. The Duma proposed that the government distribute its treasury, "monastic and imperial lands," and seize private estates as well.[49] The Duma, in fact, was preparing to alienate some of its more affluent supporters, a decision that left the assembly without the necessary political power to be efficient.

Nicholas II remained wary of having to share power with reform-minded bureaucrats. When the pendulum in 1906 elections swung to the left, Nicholas immediately ordered the Duma's dissolution after just 73 days.[50] Hoping to further marginalize the assembly, he appointed a tough prime minister, Petr Stolypin, as the liberal Witte's replacement. Much to Nicholas's chagrin, Stolypin attempted to implement some of reform (land reform), while retaining measures favorable to the regime (stepping up the number of executions of revolutionaries). After the revolution subsided, he was able to bring economic growth back to Russia's industries, a period which lasted until 1914. But Stolypin's efforts did nothing to prevent the collapse of the monarchy, nor seemed to satisfy the conservatives. Stolypin was ultimately assassinated, dying from a bullet wound by a revolutionary, Dmitry Bogrov, on September 5, 1911.[51]

Russian Constitution of 1906

The Russian Constitution of 1906 was published on the eve of the convocation of the First Duma. It was the first significant modification of the Fundamental Law of Imperial Russia that had been crafted by Mikhail Speransky in 1833. It was enacted to institute promises of the October Manifesto as well as add new reforms, but these reforms cut mostly in the Tsar's favor. The Tsar was confirmed as absolute leader, with complete control of the executive, foreign policy, church, and the armed forces. The structure of the Duma was changed, becoming a lower chamber below the State Council or Council of Ministers, and was half-elected, half-appointed by the Tsar. Legislations had to be approved by the Duma, the Council, and the Tsar to become law. The new Fundamental State Laws were the "culmination of the whole sequence of events set in motion in October 1905 and which consolidated the new status quo". The introduction of The Russian Constitution of 1906 was not simply the implementation of the October Manifesto. The introduction to the new constitution states:

- The Russian State is one and indivisible.

- The Grand Duchy of Finland, while comprising as inseparable part of the Russian State, is governed in its internal affairs by special decrees based on special legislation.

- The Russian language is the common language of the state, and its use is compulsory in the army, the navy and all state and public institutions. The use of local (regional) languages and dialects in state and public institutions are determined by special legislation.

Legacy

The revolution resulted in an attempt at some limited reforms, beginning with the October Manifesto, which created the Imperial Duma. Despite what seemed to be a moment for celebration for Russia's population and the reformists, the Manifesto was rife with problems. What might have been viewed earlier as a significant concession was now too little, too late. By October 1905, the revolution was already underway. There was no mention yet of a constitution, but even with these limited reforms, Nicholas hesitated. Witte said in 1911 that the manifesto was written only to get the pressure off the monarch's back, that it was not a "voluntary act."[52] In fact, the writers hoped that the Manifesto would sow discord into "the camp of the autocracy’s enemies" and bring order back to Russia.[53] They miscalculated.

As events proceeded the government was forced to make further concessions. The Russian Constitution of 1906, the first change to the Fundamental Law since 1833, set up a multiparty system and a limited constitutional monarchy. While it did enact a new government, it is clear that the Tsar regretted giving up any power and reneged on some of the promises made in the Manifesto. While it helped to quell public violence it served to only prolong the life of the autocracy. The provisions and the new constitutional monarchy did not satisfy the revolutionaries or most Russians, but it managed to maintain its hold on power until another disastrous war, this time World War I, created another political morass from which the regime could not survive. Lenin, as later head of the USSR, called the 1905 Russian Revolution "The Great Dress Rehearsal," without which the "victory of the October Revolution in 1917 would have been impossible."[54]

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Micheal Clodfelter, Warfare and Armed Conflicts: A Statistical Encyclopedia of Casualty and Other Figures, 1492-2015 (McFarland & Company, 2017, ISBN 978-0786474707).

- ↑ Sidney Harcave, The Russian Revolution of 1905 (London, England: Collier Books, 1970, ISBN 1199993085).

- ↑ James Defronzo, Revolutions and Revolutionary Moments (New York, NY: Routledge, 2014, ISBN 978-0813349244).

- ↑ Theda Skocpol, States and Social Revolutions: A Comparative Analysis of France, Russia and China (Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press, 1979, ISBN 978-0521224390), 93.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 Harcave 1970, 21-22.

- ↑ Harcave 1970, 19.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Harcave 1970, 20.

- ↑ Richard Pipes, A Concise History of the Russian Revolution (New York, NY: Vintage Books, 1996, ISBN 978-0679745440), 8.

- ↑ Theodore Weeks, "Russification: Word and Practice 1863–1914," Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 148, December 2004, 472.

- ↑ Mary Conroy, "Russian Civil Society: A Critical Assessment," in Civil Society in Late Imperial Russia Laura Henry, Lisa Sundstrom, and Albert Evans Jr. (eds.), (New York, NY: M.E. Sharpe, 2006, ISBN 978-0765615220), 12.

- ↑ Weeks, 473.

- ↑ Darius Staliūnas, "Between Russification and Divide and Rule: Russian Nationality Policy in the Western Borderlands in Mid-19th Century," Jahrbücher für Geschichte Osteuropas, Neue Folge 55(3), 2007.

- ↑ Weeks, 475.

- ↑ Weeks, 475–476.

- ↑ Skocpol, 90.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Skocpol, 91.

- ↑ Skocpol, 92.

- ↑ Maureen Perrie, "The Russian Peasant Movement of 1905–1907: Its Social Composition and Revolutionary Significance," Past and Present 57, November 1972, 124–125.

- ↑ Harcave 1970, 23.

- ↑ Harcave 1970, 25.

- ↑ Susan Morrissey, Heralds of Revolution: Russian Students and the Mythologies of Radicalism (Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, 1998, ISBN 978-0195115444), 20.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Morrissey, 22.

- ↑ Morrissey, 23.

- ↑ Ascher, 202.

- ↑ Rosa Luxemburg, The Mass Strike, the Political Party and the Trade Unions 1906 (tr. Patrick Lavin, 1925). Marxist Educational Society of Detroit, Chapter 4, "The Interaction of the Political and the Economic Struggle." Retrieved November 21, 2020.

- ↑ Luxemburg, Chapter 3.

- ↑ Abraham Ascher, The Revolution of 1905: A Short History (Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press, 2004, ISBN 978-0804750288), 6.

- ↑ Harrison E. Salisbury, Black Night White Snow (Boston, MA: Da Capo Press, 1981, ISBN 978-0306801549), 117.

- ↑ This petition asked for "an eight-hour day, a minimum daily wage of one ruble (fifty cents), a repudiation of bungling bureaucrats, and a democratically elected Constituend Assembly to introduce representative government into the empire." R.R. Palmer, A History of the Modern World, 2nd ed., (New York, New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1964, ASIN B0007EKEEG), 715.

- ↑ Robert Blobaum, Feliks Dzierzynski and the SDKPiL: A Study of the Origins of Polish Communism (New York, NY: East European Monographs/Columbia University Press, 1984, ISBN 978-0880330466), 123.

- ↑ Voline, The Unknown Revolution: 1917 - 1921, (Montreal, Quebec: Black Rose Books, 1975, ISBN 978-0919618251), Chapter 2.

- ↑ Neal Bascomb, Red Mutiny: Eleven Fateful Days on the Battleship Potemkin (Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin, 2007, ISBN 978-0618592067), 286-299.

- ↑ Kevin O'Connor, The History of the Baltic States (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2003, ISBN 0313323550), 58.

- ↑ B.D. Taylor, Politics and the Russian Army: Civil-Military Relations, 1689–2000 (Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press, 2003, ISBN 978-0313323553), 69.

- ↑ S.G. Wheatcroft (ed.), "The Pre-Revolutionary Period," in Challenging Traditional Views of Russian History (London, England: Palgrave Macmillan, 2002, ISBN 978-0333754610), 34.

- ↑ Richard Pipes, The Russian Revolution (New York, NY: Vintage Books, 1991, ISBN 978-0679736608), 48.

- ↑ J. N. Larned, History for Ready Reference, Vol VII (Springfield, MA: The C. A. Nichols Co., Publishers, 1910), 574. (The original source for this information, according to the book, was Professor Maksim Kovalevsky, who presented these figures in the Duma on 2 May 1906, "in the presence of M. Stolypin, who did not contest it."

- ↑ Taylor, 69.

- ↑ Nikolai Tagantsev, " "Death penalty in Russia,". Retrieved August 26, 2020.

- ↑ 683 executions by sentences of Field Courts Martial, acting from 1 September [O.S. 19 August] 1906, to 3 May [O.S. 20 April] 1907 were listed separately and not subdivided by year.

- ↑ Peter Kropotkin, The Terror in Russia 4th Ed. (London, England: Methuen & Co., 1909). Retrieved August 26, 2020.

- ↑ Robert Blobaum, Feliks Dzierzynsky and the SDKPiL: A study of the Origins of Polish Communism (New York, NY: Columbia University Press, 1984, ISBN 978-0880330466), 149.

- ↑ Martin Sixsmith, Russia: A 1,000 Year Chronicle of the Wild East (London, England: BBC Books, 2011, ISBN 978-1849900720), 171.

- ↑ Nader Sohrabi, "Historicizing Revolutions: Constitutional Revolutions in the Ottoman Empire, Iran, and Russia, 1905-1908," American Journal of Sociology, 100(6) (May 1995): 1407–1408.

- ↑ G.M. Kropotkin, "The Ruling Bureaucracy and the 'New Order' of Russian Statehood After the Manifesto of 17 October 1905," Russian Studies in History, 46(2) (Spring 2008): 23.

- ↑ G.M. Kropotkin, 23.

- ↑ Sohrabi, 1425.

- ↑ Sohrabi, 1426.

- ↑ 49.0 49.1 Sohrabi, 1427.

- ↑ Sixsmith, 173.

- ↑ Sixsmith, 174.

- ↑ G.M. Kropotkin, 6-33.

- ↑ G.M. Kropotkin, 9.

- ↑ Abraham Ascher, The Revolution of 1905: Russia in Disarray (Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press, 1994, ISBN 978-0804723275), 1–2.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Ascher, Abraham. The Revolution of 1905, vol. 1: Russia in Disarray. Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press, 1988. ISBN 9780804714365

- Ascher, Abraham. The Revolution of 1905, vol. 2: Authority Restored. Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press, 1994. ISBN 978-080472328

- Ascher, Abraham. The Revolution of 1905: A Short History. Palo Alto: Stanford University Press, 2004. ISBN 978-0804750288

- Bascomb, Neal. Red Mutiny: Eleven Fateful Days on the Battleship Potemkin. Boston. MA: Houghton Mifflin, 2007. ISBN 978-0618592067

- Blobaum, Robert. Feliks Dzierzynski and the SDKPiL: A Study of the Origins of Polish Communism. New York, NY, East European Monographs/Columbia University Press, 1984. ISBN 978-0880330466

- Bushnell, John. Mutiny amid Repression: Russian Soldiers in the Revolution of 1905–1906. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1985. ISBN 978-0253339607

- Clodfelter, Micheal. Warfare and Armed Conflicts: A Statistical Encyclopedia of Casualty and Other Figures, 1492-2015. McFarland & Company, 2017. ISBN 978-0786474707

- Coquin, François-Xavier. 1905, La Révolution russe manquée. Paris, France: Editions Complexe, 1997. ISBN 978-2870271612

- Coquin, François-Xavier, and CelineGervais-Francelle (eds.). 1905 : La première révolution russe (Actes du colloque sur la révolution de 1905). Paris, France: Publications de la Sorbonne et Institut d'Études Slaves, 1986. ISBN 2720402206

- Defronzo, James. Revolutions and Revolutionary Moments. New York, NY: Routledge, 2014. ISBN 978-0813349244

- Geifman, Anna. Thou Shalt Kill: Revolutionary Terrorism in Russia, 1894–1917. Princeton, NY: Princeton University Press, 1995. ISBN 9780691025490

- Glatter, Pete (ed.). "The Russian Revolution of 1905: Change Through Struggle," Revolutionary History 9(1), London, England: Socialist Platform, Ltd., 2005. ISBN 9780955112706

- Glatter, Pete. "1905 The consciousness factor," International Socialism, 108, October 17, 2005. Retrieved May 25, 2020.

- Harcave, Sidney. The Russian Revolution of 1905. London, England: Collier Books, 1970. ISBN 1199993085

- Henry, Laura, Lisa Sundstrom, and Albert Evans Jr. (eds.). Civil Society in Late Imperial Russia. New York, NY: M.E. Sharpe, 2006. ISBN 978-0765615220

- Luxemburg, Rosa. The Mass Strike, the Political Party and the Trade Unions. Harper & Row, 1971. ISBN 978-0061315831

- Morrissey, Susan. Heralds of Revolution: Russian Students and the Mythologies of Radicalism. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, 1998. ISBN 978-0195115444

- O'Connor, Kevin. The History of the Baltic States. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2003. ISBN 0313323550

- Pipes, Richard. A Concise History of the Russian Revolution. (New York, NY: Vintage Books, 1996. ISBN 978-0679745440

- Rawson, Donald C. Russian Rightists and the Revolution of 1905. (Cambridge Russian, Soviet and Post-Soviet Studies), Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press, 1995. ISBN 9780521464871

- Salisbury, Harrison E. Black Night White Snow. Boston, MA: Da Capo Press, 1981. ISBN 978-0306801549

- Skocpol, Theda. States and Social Revolutions: A Comparative Analysis of France, Russia and China. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press, 1979. ISBN 978-0521224390

- Sixsmith, Martin. Russia: A 1,000 Year Chronicle of the Wild East. London, England: BBC Books, 2011. ISBN 978-1849900720

- Taylor, B.D. Politics and the Russian Army: Civil-Military Relations, 1689–2000. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press, 2003. ISBN 978-0313323553

- Ury, Scott. Barricades and Banners: The Revolution of 1905 and the Transformation of Warsaw Jewry, Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press, 2012. ISBN 978-0804763837

- Voline. The Unknown Revolution: 1917 - 1921. Montreal, Quebec: Black Rose Books, 1975. ISBN 978-0919618251

- Wheatcroft, S.G. (ed.). Challenging Traditional Views of Russian History. London, England: Palgrave Macmillan, 2002. ISBN 978-0333754610

External links

All links retrieved June 13, 2023.

- The Mass Strike. Rosa Luxemburg, 1906.

- The Year 1905 by Leon Trotsky

- Russia and reform (1907) by Bernard Pares

- 1905 An article on the events of 1905 from an anarchist perspective (Anarcho-Syndicalist Review, no. 42/3, Winter 2005)

- Russian Graphic Art and the Revolution of 1905. From the collection of the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Yale University

- Revolution of 1905 in Poland (in Polish)

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.