| Hippolytus of Rome | |

|---|---|

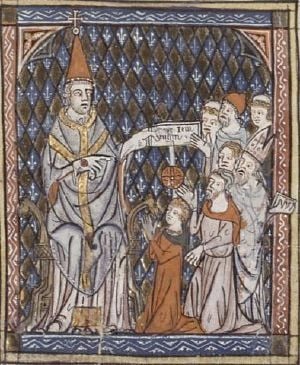

Martyrdom of Hippolytus (Paris, fourteenth century) | |

| Martyr | |

| Born | Unknown |

| Died | 235 in Sardinia |

| Venerated in | Eastern Orthodox Church |

| Feast | January 30 (martyrdom), August 13 |

| Patronage | Bibbiena, Italy; horses; prison guards; prison officers; prison workers |

Saint Hippolytus of Rome (died 235 C.E.), sometimes called Ypolitus (Ippolito (Italian)) was one of the most prolific writers of the early Church. He was born in the second half of the second century, probably in Rome. A disciple of Irenaeus of Lyon and strong opponent of opinions he considered heretical, he came into conflict with the popes of his time and for some time headed a separate congregation. He holds the distinction of being the first antipope, but he died in 235 reconciled to the Church as a martyr and is recognized as a saint. Traditionally believed to have been dragged to death by wild horses, it is more likely that he died as a result of being sentenced to hard labor as a mine worker.

Hippolytus' writings came to be highly influential in the Eastern Orthodox Church especially, where he is still venerated today. He was also highly esteemed in the early Roman Catholic tradition. His writings remain a valuable source of information regarding the history and tradition of the early Christian church.

Life

As a presbyter of the church at Rome under Bishop Zephyrinus (199-217), Hippolytus was distinguished for his learning and eloquence. Origen, then a young man, heard him preach.[1]

However, questions of theology and church discipline soon brought Hippolytus into direct and bitter conflict with Rome's bishop, Zephyrinus, who had declined to condemn certain doctrines regarding the nature of the Trinity which Hippolytus considered heretical. For this Hippolytus gravely censured him, representing him as an incompetent man, unworthy to rule the Church of Rome. He characterized the pope as a tool in the hands of the allegedly ambitious and intriguing deacon Callixtus, whose early life Hippolytus maliciously depicted in his Philosophumena (IX, xi-xii).

Hippolytus' learning and erudition made him a logical candidate to succeed Zephyrinus, but his divisiveness and unwillingness to forgive sinners argued against him. Consequently, when Callixtus was elected pope (217-218) on the death of Zephyrinus, Hippolytus immediately left the communion of the Roman Church.

He accused the new pope of favoring the Christological heresies of the Monarchians—emphasizing the oneness of God as opposed to the trinitarian notion of God being three distinct "persons" in one Being. Further, Hippolytus accused Callixtus of subverting the discipline of the Church by receiving back into the church those guilty of gross offenses, including adultery, thus establishing the tradition of eventual absolution for all repented sins. The result was a schism, and for perhaps over ten years Hippolytus stood at the head of a separate congregation, giving him the distinction of being the first anti-pope, as well as later a martyr and saint. His reign in opposition to Callixtus lasted through the succeeding pontificates of Urban I (222–230) and at least part of that of Pontian (230–235).

During or shortly after the pontificate of Pontian, the schism apparently came to an end. Under the persecution by Emperor Maximinus Thrax, Pontian and other church leaders, among them Hippolytus, were exiled by the emperor Maximinus Thrax to Sardinia in 235, where both of them died. The tradition that he was dragged to death by wild horses is apparently legendary. It is more likely that he, like Pontian, died as a result of forced mine labor. An entry in the Liberian Catalogue of bishops of Rome for the year 235 C.E. records that Hippolytus the presbyter was transported as an exile to the island of Sardinia where he gained the title of martyr by dying in the mines on August 13, 235. The Liberian Catalogue further records that the body of Hippolytus was brought to Rome from Sardinia and interred in the Via Tiburtina.[2]

The bodies of the exiles were interred in Rome, that of Hippolytus in the cemetery on the Via Tiburtina. His memory was henceforth celebrated in the Church as that of a saint and martyr.

Writings

Hippolytus's voluminous writings embrace the spheres of exegesis, homiletics, apologetics and polemic, chronography, and ecclesiastical law. His works have unfortunately come down to us in such a fragmentary condition that it is difficult to obtain from them any very exact notion of his intellectual and literary importance.

Of his exegetical works the best preserved are the Commentary on the Prophet Daniel and the Commentary on the Song of Songs. Unfortunately, the sermons attributed to him entitled the Homilies on the Feast of Epiphany are probably wrongly attributed to him, and it is thus impossible to get a sense of his vaunted skills as a preacher.

He wrote polemical works directed against pagans, Jews, and heretics. The most important of these polemical treatises is the Refutation of all Heresies, which has come to be known by the inappropriate title of the Philosophumena. Of its ten books, the second and third are lost; Book I was for a long time printed among the works of Origen; Books IV-X were found in 1842 by the Greek Minoides Mynas, without the name of the author, in an Armenian monastery at the Greek Orthodox monastic republic of Mount Athos. The mystery which enveloped the person and writings of Hippolytus began to be clarified with this discovery.

Of the dogmatic works, that on Christ and Antichrist survives in a complete state. Among other things it includes a vivid account of the events preceding the end of the world, and it was probably written at the time of the persecution under Septimius Severus, i.e. about 202. The liturgical treatise known as the Apostolic Tradition is now generally attributed to him. This work is a valuable source of information concerning the rites and liturgies of the Roman Church in the early third century.

The influence of Hippolytus was felt chiefly through his works on chronography and ecclesiastical law. His chronicle of the world, a compilation embracing the whole period from the creation of the world up to the year 234, formed a basis for many chronographical works both in both the East and the West. In the great compilations of ecclesiastical law which arose in the East since the fourth century much of the material was taken from the writings of Hippolytus or from writings attributed to him.

In the Eastern Orthodox Church, the feast day of St. Hippolytus falls on August 13, which is also the Apodosis of the Feast of the Transfiguration. The Eastern church also celebrates the feast of St. Hippolytus Pope of Rome on January 30, who may or may not be the same individual.

Legacy

Pope Damasus I dedicated to Hippolytus one of his famous epigrams.

Prudentius (Peristephano II) drew a highly colored picture of his gruesome death, the details of which are mostly legendary. In it, the pagan myth of Hippolytus the son of Theseus was apparently transferred to Hippolytus of Rome. The mythological Hippolytus, whose name means "loose horse" in Greek, had been dragged to death by wild horses. This death, according to legend, was the very method by which the historical Hippolytus became martyred. Hippolytus thus became the patron saint of horses. During the Middle Ages, sick horses were brought to St. Ippolitts, Hertfordshire, where a church was dedicated to him.

Of the historical Hippolytus little remained in the memory of later ages. Neither Eusebius[3] nor Jerome[4] knew that the author so much read in the East and the Roman saint were one and the same person. Some scholars find it unlikely that they were, alleging that differing levels of development of the doctrine of the Trinity indicates differing dates of composition.

In 1551 a marble statue of a seated man was found in the cemetery of the Via Tiburtina: on the sides of the seat were carved a paschal cycle, and on the back the titles of numerous writings. It was the statue of Hippolytus, a work of the third century. At the time of Pius IX, it was placed in the Lateran Museum, a record in stone of a lost tradition of Hyppolytus' veneration.

Bibliography

The edition of J.A. Fabricius, Hippolyti opera graece et latine (2 vols., Hamburg, 1716–1718), reprinted in Gallandi, Bibliotheca veterum patrum (vol. II, 1766), and Migne, Cursus patrol. ser. Graeca, (vol. X) is out of date. The preparation of a complete critical edition has been undertaken by the Prussian Academy of Sciences. The task is one of extraordinary difficulty, for the textual problems of the various writings are complex and confused: the Greek original is extant in a few cases only (the Commentary on Daniel, the Refutation, on Antichrist, parts of the Chronicle, and some fragments); for the rest we are dependent on fragments of translations, chiefly Slavonic, all of which were not even published (as of 1911).

Of the Academy's edition one volume was published at Berlin in 1897, containing the Commentaries on Daniel and on the Song of Songs, the treatise on Antichrist, and the Lesser Exegetical and Homiletic Works, edited by Georg Nathaniel Bonwetsch and Hans Athelis.

The Commentary on the Song of Songs has also been published by Bonwetsch (Leipzig, 1902) in a German translation based on a Russian translation by Nicholas Marr of the Georgian text, and he added to it (Leipzig, 1904) a translation of various small exegetical pieces, which are preserved in a Georgian version only (The Blessing of Jacob, The Blessing of Moses, The Narrative of David and Goliath)—A great part of the original of the Chronicle has been published by Adolf Bauer (Leipzig, 1905) from the Codex Matritensis Graecus, 221. For the Refutation we are still dependent on the editions of Miller (Oxford, 1851), Duncker and Schneidewin (Göttingen, 1859), and Cruice (Paris, 1860). An English translation is to be found in the Ante-Nicene Christian Library (Edinburgh, 1868–1869).

Notes

- ↑ Jerome's De Viris Illustribus # 61; cp. Eusebius, Historia Ecclesiastica vi. 14, 10.

- ↑ Hippolytus of Rome www.ccel.org. Retrieved February 20, 2008.

- ↑ Historia Ecclesiae vi. 20, 2

- ↑ Vir. ill. 61

See also

- Apostolic Tradition

- Epistle to Diognetus

- Canons of Hippolytus

- Josephus's Discourse to the Greeks concerning Hades (actually by Hippolytus)

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- This article incorporates text from the Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition, a publication now in the public domain.

- Achelis, Hans. Hippolytstudien. Leipzig, 1897.

- Bunsen, Christian Charles Josias. Hippolytus and his Age. 1852, 2nd ed.; 1854; Ger. ed.; 1853.

- d'Ales, Adhémar. La Theologie de Saint Hippolyte. Paris, 1906.

- Döllinger, Johann Joseph Ignaz von Döllinger. Hippolytus und Kallistus. Regensb. 1853; Eng. transl., Edinb., 1876.

- Ficker, Gerhard. Studien zur Hippolytfrage. Leipzig, 1893.

- Johannes Neumann, Karl. Hippolytus von Rom in seiner Stellung zu Staat und Welt. Leipzig, 1902.

- Lightfoot, J.B. The Apostolic Fathers vol. i, part ii. London, 1889-1890.

External links

All links retrieved July 17, 2024.

- Against Noetus www.newadvent.org

- Refutation of All Heresies www.newadvent.org

- Catholic Encyclopedia: St. Hippolytus of Rome www.newadvent.org

- Encyclopaedia Britannica, Hippolytus of Rome www.britannica.com

- Hieromartyr Hippolytus the Pope of Rome (January 30) Orthodox icon and synaxarion, ocafs.oca.org

- Martyr Hippolytus of Rome ocafs.oca.org

| |||||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.