| Saint Thomas the Apostle | |

|---|---|

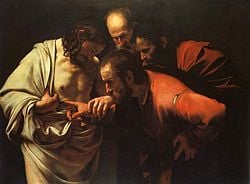

"The Incredulity of St Thomas" by Caravaggio | |

| Doubting Thomas | |

| Died | c. 72 in near Madras, India |

| Venerated in | Catholic Church, Eastern Orthodox Church, Anglican Church, Lutheran Church, some Protestant Churches |

| Feast | July 3, December 21 (L), 26 Pashons (Coptic Orthodox) |

| Attributes | The Twin, placing his finger in the side of Christ, spear (means of martyrdom), square (his profession, a builder) |

| Patronage | Architects, India, and others, see [1] |

Saint Thomas the Apostle (also known as Judas Thomas or Didymus, meaning "Twin") was one of the Twelve Apostles of Jesus who is best known for doubting the resurrection of Jesus and demanding to feel Jesus' wounds before being convinced (John 20:24-29). This story is the origin of the term "Doubting Thomas." After seeing Jesus alive, Thomas professed his faith in Jesus, exclaiming "My Lord and my God!" presenting one of the first clear declarations of Christ's divinity.

As an apostle, Saint Thomas was called to spread Jesus' teachings throughout the nations. While Saints Peter and Paul were said to have brought the gospel to Greece and Rome, Thomas was said to have taken it eastwards as far as India. The churches of Malankara in India trace their roots back to St. Thomas who, according to local tradition, arrived along the Malabar Coast in the year 52 C.E.

Saint Thomas is also associated with a collection of ancient documents that bear his name. These documents include the Gospel of Thomas, the Acts of Thomas, and the Infancy Gospel of Thomas. In the ancient world, it was common to attribute texts to an apostle or religious teacher even if they were not the true authors.

Saint Thomas is revered as a saint in both the Roman Catholic Church, in the Eastern Orthodox Church and in Oriental Orthodoxy, and is remembered each year on Saint Thomas Sunday, which is always one week after Easter.

Identity

There has been, and continues to be, disagreement and uncertainty as to the identity of Saint Thomas. In three biblical passages (John 11:16; 20:24; and 21:2), Thomas is identified as "Thomas, also called the Twin (Didymus)." The Aramaic Tau'ma: The name "Thomas" itself comes from the Aramaic word for twin: T'oma (תאומא). Thus, the name convention Didymus Thomas thrice repeated in the Gospel of John is in fact a tautology that omits the Twin's actual name.

The Nag Hammadi "sayings" Gospel of Thomas begins: "These are the secret sayings that the living Jesus spoke and Didymos Judas Thomas recorded." Syrian tradition also states that the apostle's full name was Judas Thomas, or Jude Thomas. Some have seen in the Acts of Thomas (written in east Syria in the early third century, or perhaps as early as the first half of the second century) an identification of Saint Thomas with the apostle Judas son of James, better known in English as Jude. However, the first sentence of the Acts follows the Gospels and the Acts of the Apostles in distinguishing the apostle Thomas and the apostle Judas son of James. Few texts identify Thomas's other twin, though in the Book of Thomas the Contender, part of the Nag Hammadi library, it is said to be Jesus himself: "Now, since it has been said that you are my twin and true companion, examine yourself…"[1]

Some have claimed that the mainstream Christian tradition has mistakenly divided the person of Jude the Twin and rendered one man as two, both Saint Jude and Saint Thomas. However, the lists of the Twelve in Luke 6 and Acts 1 clearly treat Judas son of James (St. Jude) and Thomas as separate people. Mainstream Christian churches follow this by regarding the two Apostles as separate individuals.

In the Syriac tradition, St. Thomas is referred to as Mar Thoma Sleeha, which translate roughly as Lord/Saint Thomas the Apostle.

History

Eusebius of Caesarea (Historia Ecclesiastica, III.1) quotes Origen (died mid-third century) as having stated that Thomas was the apostle to the Parthians, but Thomas is better known as the missionary to India through the Acts of Thomas, written c. 200. In Edessa, where his remains were venerated, the poet Ephrem the Syrian (died 373 C.E.) wrote a hymn in which the Devil cries:

- …Into what land shall I fly from the just?

- I stirred up Death the Apostles to slay, that by their death I might escape their blows.

- But harder still am I now stricken: the Apostle I slew in India has overtaken me in Edessa; here and there he is all himself.

- There went I, and there was he: here and there to my grief I find him.[2]

A long public tradition in the church at Edessa honoring Thomas as the Apostle of India resulted in several surviving hymns that are attributed to Ephrem, copied in codices of the eighth and ninth centuries. References in the hymns preserve the tradition that Thomas' bones were brought from India to Edessa by a merchant, and that the relics worked miracles both in India and at Edessa. A pontiff assigned his feast day and a king erected his shrine. The Thomas traditions became embodied in Syriac liturgy, thus they were universally credited by the Christian community there. There is also a legend that Thomas had met the Biblical Magi on his way to India.

The indigenous church of Kerala State, India has a tradition that St. Thomas sailed there to spread the Christian faith. He is said to have landed at a small port village, named Palayoor, near Guruvayoor, which was a priestly community at that time. Here he conversed with the community. Four prominent rich and priestly Hindu families accepted the Christian faith and are said to have been baptized by St. Thomas himself. He left Palayoor in 52 C.E., for southern Kerala State, where he established the Ezharappallikal, or "Seven and Half Churches." These churches are at Kodungallur, Kollam, Niranam, Nilackal (Chayal), Kokkamangalam, Kottakkayal (Paravoor), Palayoor (Chattukulangara), and Thiruvithamkode (Travancore)—the half church.

Visit to Gondophares

The Acts of Thomas (Ch. 17) describes Saint Thomas' visit to King Gondophares in northern India. When Acts was being composed, there was no reason to suppose that a king named "Gondophares" had ever really existed. However, the discovery of his coins in the region of Kabul and the Punjab, and the finding of a votive inscription of his 26th regal year that was unknown until 1872, provided evidence that his reign commenced in 21 C.E. until c. 47 C.E. Thus, one scholar surmises, "It is impossible to resist the conclusion that the writer of the Acts must have had information based on contemporary history. For at no later date could a forger or legendary writer have known the name."[3] Though the Acts are usually considered to be moral entertainments of a legendary nature, the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea is a surviving, roughly contemporary guide to the routes commonly used for navigating at the time in the Arabian Sea.

Return of the relics

In 232 C.E., the relics of the Apostle Thomas are said to have been returned by an Indian king and brought back from India to the city of Edessa, Mesopotamia, on which occasion his Syriac, Acts of Thomas, were written. The Indian king is named as "Mazdai" in Syriac sources, "Misdeos" and "Misdeus" in Greek and Latin sources respectively, which has been connected to the "Bazdeo" on the Kushan coinage of Vasudeva I, the transition between "M" and "B" being a current one in Classical sources for Indian names.[4]

After a short stay in the Greek island of Chios, on September 6, 1258, the relics were transported to the West, and now rest in Ortona, Italy.

Indian legacy

Southern India had maritime trade with the West since ancient times. Egyptian trade with India and Roman trade with India flourished in the first century C.E. In 47 C.E., the Hippalus wind was discovered and this led to direct voyage from Aden to the South Western coast in 40 days. In the writings of Pliny (23-79 C.E.), Muziris (Kodungallur) and Nelcyndis, or Nelkanda (near Kollam) in South India, are mentioned as flourishing ports, Pliny has given an accurate description of the route to India, and referred to the flourishing trade in spices, pearls, diamonds and silk between Rome and Southern India. Though the Cheras controlled Kodungallur port, Southern India belonged to the Pandyan Kingdom, which had sent embassies to the court of Augustus Caesar.

According to tradition, St. Thomas landed in Kodungallur in 52 C.E., in the company of a Jewish merchant, Hebban. There were Jewish colonies in Kodungallur since ancient times, and Jews continue to reside in Kerala, tracing their ancient history there. The Jewish Christians were supported from Mesopotamia and Persia.

As recorded in the Travancore Manual, around 345 C.E., Thomas Cana (Kona Thomas), merchant and missionary, visited the Malabar coast. He brought to Kodungallur a group of four hundred Christians from Baghdad, Nineveh, and Jerusalem. Cheraman Perumal, the King, gave him grants of privileges.

In 522 C.E., Cosmos Indicopleustes visited the Malabar Coast. He is the first traveler who mentions Syrian Christians in Malabar. He mentions that in the town of 'Kalliana' (Quilon or Kollam), there is a bishop consecrated in Persia. There is a copper plate grant given to Iravi Korttan, a Christian of Kodungallur (Cranganore), by King Vira Raghava. The date is estimated to be around 744 C.E. In 822 C.E., two Nestorian Persian Bishops Mar Sapor and Mar Peroz came to Malabar, to occupy their seats in Kollam and Kodungallur, to look after the local Syrian Christians (also known as St. Thomas Christians).

In the thirteenth century, Marco Polo, who visited South Indian cities of Kayal in the East Coast and Kollam (Quilon), mentioned in his writings about the Syrian Christians of Quilon and also about the Thomas tomb on the East Coast, near Kayal, confirming the tradition that St Thomas died in South India.

While exploring the Malabar coast of Kerala following Vasco Da Gama's arrival in Calicut in 1498, the Portuguese encountered Christians in South Western India, who traced their foundations to Thomas. However, the Catholic Portuguese did not accept the legitimacy of local Malabar traditions, and they began to impose Roman Catholic practices upon the Saint Thomas Christians. The Udayamperoor Synod (Synod of Diamper) in 1599, was an attempt by the Portuguese to Latinize the local Christian rites. In 1653, the Syrian Christians split from the Latin Church controlled by the Pope of Rome. The Orthodox faction remained fully within the various Oriental Orthodox and Assyrian traditions.

On the isolated island of Socotra, south of Yemen in the Arabian Sea, a community of Christians had been attested as early as c. 354, by Philostorgius, the Arian Church historian, in his narrative of the mission of Bishop Theophilus to the Homeritae, and was confirmed by medieval Arab sources. They survived to be documented in 1542, by Saint Francis Xavier, whom they informed that their ancestors had been evangelized by Thomas.[5] Francis Xavier was careful to station four Jesuits to guide the faithful in Socotra into orthodoxy. Socotra had been briefly garrisoned by Albuquerque, but after the Mahra sultans from the Horn of Africa conquered Socotra, in 1511, almost all traces of the Thomas Christian community in Socotra had been utterly effaced.

Near Chennai (formerly Madras) in India stands a small hillock called St. Thomas Mount, where the Apostle is said to have been killed in 72 C.E. (although the exact year is not established). Also to be found in Chennai is the San Thome Cathedral Basilica, to which his mortal remains were supposedly transferred.

Pope Benedict XVI's controversial statements

On September 27, 2006, Pope Benedict XVI gave out a speech in the Vatican in which he recalled an ancient tradition claiming that Thomas first evangelized Syria and Persia, then went on to Western India, from where Christianity also reached Southern India.[6] Since this statement was perceived to be a direct violation of the religious beliefs of many Saint Thomas Christians in India, they condemned this statement.[7] Later, the Vatican amended the published text of the same speech with minor modifications owing to the anger expressed by the Saint Thomas Christians.[8]

Thomas in East Asia

Various Eastern Churches in China and Japan claim that St. Thomas personally brought Christianity to China and Japan in 64 and 70 C.E., respectively. This view is promulgated by the Keikyo Institute.[9]

Writings attributed to Thomas

In the first two centuries of the Christian era, a number of writings were circulated, which claimed the authority of Thomas. It is unclear now why Thomas was seen as an authority for doctrine, although this belief is documented in Gnostic groups as early as the Pistis Sophia (c. 250-300 C.E.), which states that the "three witnesses" committing to writing "all of his words" are Thomas, along with Saint Philip and Saint Matthew (Pistis Sophia 1:43).

The most famous work ascribed to Saint Thomas is the "sayings" document, commonly called the Gospel of Thomas, which is a non-canonical work which some scholars believe may actually predate the writing of the Biblical gospels themselves.[10] The opening line claims it is the work of "Didymos Judas Thomas"—who has been identified with Thomas. This work was discovered in a Coptic translation in 1945, at the Egyptian village of Nag Hammadi, near the site of the monastery of Chenoboskion. Once the Coptic text was published, scholars recognized that an earlier Greek translation had been published from fragments of papyrus found at Oxyrhynchus in the 1890s.

In addition to the Gospel of Thomas, other works were also attributed to him, including he Acts of Thomas and the Infancy Gospel of Thomas, which relates the miraculous events and prodigies of Jesus' boyhood. This is the document that tells for the first time the familiar legend of the twelve sparrows which Jesus, at the age of five, fashioned from clay on the Sabbath day, which took wing and flew away. The earliest manuscript of this work is a sixth century one in Syriac. This gospel was first referred to by Irenaeus.

The Gospel of Thomas was eventually rejected from the Christian canon due to its gnostic elements. Thus, in the fourth century Cyril of Jerusalem stated: "Let none read the gospel according to Thomas, for it is the work, not of one of the twelve apostles, but of one of Mani's three wicked disciples" (Cathechesis V).

Scholar Elaine Pagels sees certain verses in the Gospel of John as refutations of Thomasine thought and a valuable illustration of how the early Christian communities lobbied for their version of Christ and his message. "I'm not saying [John] was responding to Thomas as written, because there may not have been a written text [yet]," she says. "But after you study them, it is inconceivable that the Gospel of John is not responding to some of these ideas." In her book Beyond Belief, Pagels adopts an argument proposed by Claremont Graduate University religion professor Gregory Riley. John's author, she says, was infuriated by Thomas' suggestion that Christians could gain salvation through esoteric knowledge and internal quest rather than straightforward belief in Jesus' divinity and atoning sacrifice. She claims that John "hammers home" that displeasure in a series of prickly interactions between Christ and the Apostle Thomas. Of course, this point of view is entirely based on an assumption that the Biblical Thomas was the writer of the Gnostic "Gospel of Thomas," and would therefore be at odds with traditional Christian doctrine.

The incidents culminate in John's indelible post-Resurrection portrait of Doubting Thomas, a man so obsessed with what he can "know" that he is blind to the greatest spiritual truth in human history. For, it is Thomas who announces that he will not believe in the risen Christ "unless I see the mark of the nails in his hands, and put my … hand in his side." When Jesus presents precisely this proof, writes Pagels, "Thomas, overwhelmed, capitulates and stammers out the confession, 'My Lord and my God!'" Jesus then turns pointedly to the other disciples and says, "Thomas, you have believed because you have seen, blessed are those who have not seen, and yet believe."

"John may have felt some satisfaction writing this scene," Pagels ventures. "In place of Thomas' cryptic sayings, John offers a simple formula: 'God loves you; believe, and be saved.'"[11]

Biblical accounts

In addition to the above mentioned "Doubting Thomas" verses (John 20:24-29), Saint Thomas also appears in several other biblical passages, such as John 11:16, in which the disciples are resisting Jesus' decision to return to Judea, where the Jews had previously tried to stone Jesus, when Thomas says: "Let us also go, that we might die with him" (New International Version).

Thomas also speaks up at The Last Supper in John 14:5. Here, Jesus assures his disciples that they know where he is going, but Thomas protests that they don't know at all. Jesus replies to this and to Philip's requests with a detailed and difficult exposition of his relationship to God the Father.

Later mythology

According to The Passing of Mary, a text attributed to Joseph of Arimathea, Thomas was the only witness of the Assumption of Mary into heaven. The other apostles were miraculously transported to Jerusalem to witness her death. Thomas was left in India, but after her burial he was transported to her tomb, where he witnessed her bodily assumption into heaven, from which she dropped her girdle. In an inversion of the story of Thomas's doubts, the other apostles are skeptical of Thomas's story until they see the empty tomb and the girdle.[12] Thomas' receipt of the girdle is commonly depicted in medieval and pre-Tridentine Renaissance art.

Notes

- ↑ John D. Turner, The Book of Thomas. Retrieved September 10, 2006.

- ↑ Medlycott 1905, ch. ii.

- ↑ Medlycott 1905.

- ↑ Mario Bussagli, "L'Art du Gandhara," p 255.

- ↑ Medlycott, 1905, ch. ii.

- ↑ Times of India, Pope Benedict XVI's comments. Retrieved March 20, 2008.

- ↑ Human Rights Kerala, Pope pops St Thomas Bubble. Retrieved March 20, 2008.

- ↑ Catholic News, Pope Releases Amended Speech. Retrieved March 20, 2008.

- ↑ Keikyo Institute, Christian Designs Found in Tomb Stones of Eastern Han Dynasty. Retrieved March 20, 2008.

- ↑ Google Books, The Tao of Thomas, by Joseph Lumpkin. Retrieved March 20, 2008.

- ↑ David Van Biema, Time Magazine Article. Retrieved March 20, 2008.

- ↑ www.ccel.org, The Passing of Mary. Retrieved March 20, 2008.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Howard, George Broadley. The Christians of Saint Thomas and Their Liturgies. Kessinger Publishing, 2006. ISBN 978-1425497330

- Kurikilamkatt, James. First Voyage of the Apostle Thomas: Ancient Christianity in Bharuch and Taxila. ATF Press, 2007. ISBN 978-8170863595

- Medlycott, A.E. India And The Apostle Thomas: An Inquiry With A Critical Analysis Of The Acta Thomae. Kessinger Publishing, LLC, 2007. ISBN 978-0548181980

- Ruffin, Bernard and C. Bernard Ruffin, The Twelve: The Lives of the Apostles After Calvary. Our Sunday Visitor, 1998. ISBN 978-0879739263

- Wald, S. N. Saint Thomas, the Apostle of India. Sat-Prachar Press, 1952.

External links

All links retrieved December 22, 2022.

- A.E. Medlycott, India and the Apostle Thomas, London 1905 (e-text).

- Catholic Encyclopedia: St. Thomas the Apostle.

- Passages to India.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.