Shamash

In Mesopotamian religion Shamash was the Akkadian name of the sun god, corresponding to Sumerian Utu. In mythology, Shamash was the son of the moon god Sin (known as Nanna in Sumerian), and thus the brother of the goddess Ishtar (Sumerian: Inanna), who represented the great "star" of Venus. In early inscriptions, Shamash’s consort was the goddess Aya, whose role was gradually merged with that of Ishtar. In later Babylonian astral mythology, Sin, Shamash, and Ishtar formed a major triad of divinities, which still today plays an important role in astrological systems, though under different names.

In addition to being the god of the sun, Shamash was also the deity of justice. An inscription left by King Hammurabi indicates that his famous law code was inspired and promulgated at Shamash's command. In some cases, Shamash was seen as governing the entire universe and was pictured as a king on his royal throne with his staff and signet ring.

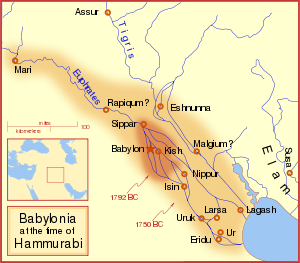

Shamash is depicted as overcoming darkness and death. In the Epic of Gilgamesh he assisted the hero's victory over the monster Humbaba, guardian of the deep forests of Lebanon. Like the later Apollo, he made his daily journey through the heavens, either on horseback, in a chariot, or on a boat. His main cult center in Sumer was the city of Larsa, and in Akkad his primary temple was in Sippar. In Canaanite tradition, the sun god was Shemesh, the "torch of the gods," but was described as female. The worship of Shemesh/Shamash was also practiced among the Israelites, although it was forbidden by the prophets and biblical writers.

History and meaning

The name Shamash simply means "sun." Both in early and in late inscriptions, Shamash is designated as the "offspring of Nanna," the moon god. In the Mesopotamian pantheon, Nanna (known as Sin in Akkadian) generally takes precedence over Shamash, since the moon was both the basis of the calendar and associated with cattle. As farming came to the fore, the sun god came to play a gradually increasing role.

The two chief centers of sun worship in Babylonia were Sippar, represented by the mounds at Abu Habba, and Larsa, represented by the modern Senkerah. At both places, the chief sanctuary bore the name E-barra (or E-babbara) meaning "Shining House" in allusion to the brilliance of Shamash. The temple at Sippar was the most famous, but temples to Shamash were erected in all large population centers, including Babylon, Ur, Mari, Nippur, and Nineveh.

Shamash in the Epic of Gilgamesh

In the Babylonian Epic of Gilgamesh, it is with Shamash's blessing and support that Gilgamesh and his companion Enkidu travel to the forest of Lebanon to slay the forest guardian Humbaba. Here, the heroes act on Shamash's behalf to enter the realm of darkness, conquer the monster who protects it, and take home its treasure in the form of the famed cedars of Lebanon. Gilgamesh beseeches his mother to pray for him to Shamash for protection:

- I must now travel a long way to where Humbaba is,

- I must face fighting such as I have not known,

- and I must travel on a road that I do not know!

- Until the time that I go and return,

- until I reach the Cedar Forest,

- until I kill Humbaba the Terrible,

- and eradicate from the land something baneful that Shamash hates,

- intercede with Shamash on my behalf.

She responds by going up to the roof of her palace to offer her prayers. "She set incense in front of Shamash, she offered fragrant cuttings, and raised her arms to Shamash." Before setting out, Gilgamesh and Enkidu make a pilgrimage to the Temple of Shamash, where they, too, make their formal offerings. During the heroes' journey, each morning they pray and make libations to Shamash in the direction of the rising sun to ensure their safe travels. Shamash guides Gilgamesh through dreams, appearing to him as a wild bull, and giving him a timely tactical warning, and finally providing a miraculous series of winds which enable Gilgamesh and Enkidu to prevail.

- Shamash raised up against Humbaba mighty tempests—

- Southwind, Northwind, Eastwind, Westwind, Whistling Wind, Piercing Wind, Blizzard, Bad Wind, Wind of Simurru,

- Demon Wind, Ice Wind, Storm, Sandstorm—

- thirteen winds rose up against him and covered Humbaba's face.

- He could not butt through the front, and could not scramble out the back,

- so that Gilgamesh'a weapons could reach out and touch Humbaba.

- Humbaba begged for his life, saying to Gilgamesh...

- "(It was) at the word of Shamash, Lord of the Mountain,

- that you were roused.

- O scion of the heart of Uruk, King Gilgamesh!"

Characteristics

In inscriptions, the attribute most commonly associated with Shamash is justice. Just as the sun disperses darkness, so Shamash brings wrong and injustice to light. King Ur-Engur of the Ur dynasty (c. 2600 B.C.E.) declared that he rendered decisions "according to the just laws of Shamash." Hammurabi attributed to Shamash the inspiration that led him to gather the existing laws and legal procedures into his famous code. In the design accompanying the code, Hammurabi is represented as receiving his laws from Shamash as the embodiment of justice. "By the command of Shamash, the great judge of heaven and earth," declares Hammurabi, "let righteousness go forth in the land; by the order of Marduk, my lord, let no destruction befall my monument."

Shamash was also regarded as a god who released sufferers from the grasp of the demons. The sick appealed to Shamash as the god who can be depended upon to help those who are suffering unjustly. This aspect of Shamash is vividly brought out in hymns addressed to him, which are considered among the finest productions in the realm of Babylonian literature.

To his devotees, Shamash was sovereign over the natural world and mankind, much like the later monotheistic deity of Judaism. The following excerpt from the work known today as the Great Hymn to Shamash is a prime example to this attitude:

- You climb to the mountains surveying the earth,

- You suspend from the heavens the circle of the lands.

- You care for all the peoples of the lands,

- Whatever has breath you shepherd without exception,

- You are their keeper in upper and lower regions.

- Regularly and without cease you traverse the heavens,

- Every day you pass over the broad earth…

- You never fail to cross the wide expanse of sea…

- Shamash, your glare reaches down to the abyss

- So that monsters of the deep behold your light…

- At your rising the gods of the land assemble…

- The whole of mankind bows to you.[1]

Scholars believe that the tradition of Shamash worship at Sippar and Larsa eventually overshadowed earlier local sun-deity traditions elsewhere and led to the absorption of these deities by the predominating cult of Shamash. In the maturing Babylonian pantheon these minor sun gods became attendants in Shamash's service. Included among them are his attendants Kettu ("justice"), Mesharu ("right"), and Bunene, his chariot driver, whose consort is Atgi-makh. Other sun deities such as Ninurta and Nergal, the patron deities of other important centers, retained their independent existences as certain phases of the sun, with Ninurta becoming the god of the morning and springtime, and Nergal the god of the noon and the summer solstice.

Together with Sin and Ishtar, Shamash formed a triad of gods which completed the even older trinity of Anu, Enlil, and Ea, representing the heavens, earth and water, respectively. The three powers of Sin, Shamash, and Ishtar symbolized three great forces of nature: The sun, the moon, and the morning star (or love and fertility). At times, instead of Ishtar, one finds Adad, the storm god, as the third person of this triad, and it may be that these two sets of triads represent the doctrines of two different schools of theological thought in Babylonia. From the time of Hammurabi onward, the triads of astral deities were placed under the dominion of the supreme deity of Marduk, who inherited the position of "King of the Gods." To the West, in Canaan, Shamash came to be known by the name Shemesh and took on a feminine character with Baal-Hadad playing the predominant role.

The consort of Shamash was known as Aya. She is, however, rarely mentioned in the inscriptions except in combination with Shamash.

Shamash in Canaanite and Hebrew tradition

In Canaan, Shemesh (Hebrew: שמש), also Shapesh (Hebrew: שפש), or Shapshu, was the Canaanite goddess of the sun, daughter of El and Asherah. She was known as "torch of the gods" and is considered an important deity in Canaanite pantheon. Her main temple was probably housed near modern Beit Shemesh, originally named after the deity.

In the Epic of Ba'al, Shemesh appears several times as El's messenger. She plays a more active role when she helps the goddess Anat bury and mourn Baal, the god of rainstorms and fertility, after he is killed by Mot, the desert god of death. She then stops shining, but is persuaded to radiate her warmth once again by Anat. After Anat defeats Mot in battle, Shemesh descends to the Underworld and retrieves Baal's body, allowing his resurrection and the eventual return of spring. In the final battle between Baal and Mot, she declares to Mot that El has now given his support to Baal, a decree which ends the battle and signals spring's return.

In the Hebrew Bible, worshiping Shemesh was forbidden and theoretically punishable by stoning, although it is doubtful that this was enforced. Psalm 19 praises the sun in tones not unlike those of the Babylonian hymns to Shamash, while making sure to place the sun firmly under Yahweh's jurisdiction:

- In the heavens he has pitched a tent for the sun,

- which is like a bridegroom coming forth from his pavilion,

- like a champion rejoicing to run his course.

- It rises at one end of the heavens

- and makes its circuit to the other;

- nothing is hidden from its heat.

The name of the judge Samson is based on the word shemesh, and one rabbinical tradition compares his strength to the sun's power. In the Bible, worshiping Shemesh described as including bowing to the east as well as rituals or iconography related to horses and chariots. King Hezekiah and possibly other Judean kings used royal seals with images similar to the Assyrian depiction of Shamash. King Josiah attempted to abolish sun worship (2 Kings 23), although the prophet Ezekiel claimed that it was prominent again in his day, even in the Temple of Jerusalem itself (Ezekiel 8:16). In Jewish tradition, the Hanukkah menorah has an extra light, called the shamash, which is used to light the eight other lights.

See also

Notes

- ↑ AngelFire, Great Hymn to Shamash, Tanslation based on that of W. G. Lambert. Retrieved December 31, 2008.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Black, Jeremy A., Graham Cunningham , Eleanor Robson, and Gabor Zolyomi (eds.). The Literature of Ancient Sumer. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004. ISBN 9780199296330.

- Finkel, Irving L., and Markham J. Geller. Sumerian Gods and Their Representations. Cuneiform monographs, 7. Groningen: STYX Publications, 1997. ISBN 9789056930059.

- Lambert, W. G. The Historical Development of the Mesopotamian Pantheon: A Study in Sophisticated Polytheism. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1975. OCLC 270102751

External links

All links retrieved January 27, 2023.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.