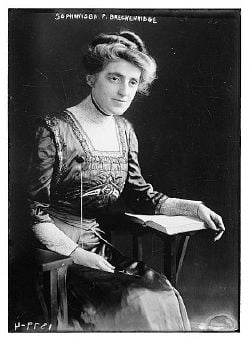

| Sophonisba Preston Breckinridge | |

Lawyer, educator, social scientist, civil rights activist

| |

| Born | April 1, 1866 Lexington, Kentucky |

|---|---|

| Died | July 30 1948 (aged 82) Chicago, Illinois |

| Occupation | economist, social work researcher, political scientist, lawyer, suffragist, mathematics teacher, diplomat |

| Parents | Issa Desha Breckinridge (1843–1892) and William Campbell Preston Breckinridge (1837–1904) |

Sophonisba Preston Breckinridge (April 1, 1866 – July 30, 1948), was an American social worker and reformer, the pioneer of the social work education movement in the United States. Breckinridge was originally educated in the law, being the first woman to be admitted to the Bar association in her native Kentucky. She went on to study political science, and became the first woman to receive a Ph.D. in the field from the University of Chicago. She became interested in social work through her connection with the Hull House social settlement, where she lived for several years. As an academic, she focused her energies on the education of social workers, instituting standards for social work education that were adopted throughout the United States. She was also active with several reform movements, including the NAACP and work with women's suffrage. Her achievements laid the foundation for improvements in the working and living conditions of people for many generations.

Life

Sophonisba Preston Breckinridge was born on April 1, 1866 in Lexington, Kentucky, the second of seven children of Issa Desha and William Campbell Preston Breckinridge. Her father was a member of Congress and a distinguished lawyer, while her great-grandfather John Breckinridge (1760-1806) was a Senator of Kentucky and Attorney General under Thomas Jefferson.

Sophonisba Breckinridge graduated from Wellesley College in 1888 and worked as a school teacher in Washington, DC. After spending one year in Europe she decided to study law at her father's office. Although her father did not agree with this, Breckinridge continued as planned. Later in 1894, she became the first woman to be admitted to the Kentucky bar.

In the late 1890s, Breckinridge decided to move to Oak Park, Illinois, and enroll in the doctoral program in the University of Chicago. She became the first woman to receive a doctoral degree in political science from Chicago in 1901, and completed her J.D. from the law school in 1904.

In 1906, Breckinridge come in contact with Edith Abbott and started to work on issues of women’s employment and juvenile delinquency. At the same time she was writing for the American Journal of Sociology and began teaching in the Chicago Social Science Center for Training and Practical Training in Philanthropic and Social Work, later renamed the School of Civics and Philanthropy. She became the assistant to Julia Lathrop, then director of research and co-director of the Center. In 1908, Lathrop stepped down and Breckinridge became the head of the school’s research department. She took Edith Abbott for her assistant.

In 1907, Breckinridge entered the Hull House settlement, staying there until 1920. The same year she became a member of the Women's Trade Union League, and founded the Immigrant's Protective League. In 1909, she became an assistant professor in the University of Chicago’s new department of household administration. In 1920, she negotiated merging of the School of Civics and Philanthropy with the University of Chicago, making the latter the center of social work in America.

As she worked in academia, Breckinridge became increasingly involved with research on different social problems. She focused on subjects as housing, immigration, minorities, and working conditions of women. She also worked as Chicago’s health inspector and campaigned for federal child labor laws. With her help the Journal of Social Service Review was started in 1927. She was also an early and active member of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in Chicago.

In 1925, she became full-time professor at the Graduate School of Social Service Administration, introducing new methods in training social workers. With that she set the standard for social-work education in the United States.

In 1933, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt named Breckinridge to be a delegate to the Pan-American Congress in Montevideo, the first women to be awarded this honor. In 1934, she was elected president of the American Association of Schools of Social Work.

Sophonisba Breckinridge died in 1948 in Chicago, from a perforated ulcer and arteriosclerosis, aged 82.

Work

Sophonisba Breckinridge believed that social research could be used to create better society. Her legal training and academic background gave her a strong foundation in her work. She pioneered the use of research in fieldwork, and advocated that social work needs to be grounded in social theory. She rejected the purely vocational approach to social work that was predominantly used in her time. According to her, scientific analysis and scholarly research need to be applied in dealing with practical social problems. Only then can change take root. Because of her insistence on a scientific approach to social work, she was sometimes criticized as being too academic.

One of the greatest accomplishments of Breckinridge was in the field of social-work education. She started as assistant to Julia Lathrop in the School of Civics and Philanthropy, and soon became dean of the school. However, as the school was without funding, Breckinridge had to negotiate the merging of the school with the University of Chicago. This was the first graduate school of social work in the United States to become affiliated with a major research university.

Breckinridge pioneered the use of mapping and canvassing in their work, recording maps of whole areas, giving a social picture of the people living in those areas. The maps helped her to more effectively present her arguments.

Some of her other contributions to social reforms include obtaining congressional support for a national study of children and women wage earners, which led to the Report on Condition of Woman and Child Wage Earners in the United States. The report revealed miserable working conditions, unsafe and exploitative in nature, under which women and children earned wages. This report contributed toward subsequent reforms improving the working conditions of women, and the abolition of child labor.

Legacy

Sophonisba Breckinridge's legacy includes being the first woman elected to several important positions. She was the first woman elected to the Kentucky bar, and became the first woman to receive a doctoral degree in political science from the University of Chicago. With that she paved the path for many women who followed in her steps.

With her pioneering work in different social areas she contributed toward many reforms, including the abolition of child labor, improvements in working conditions for women, and advancing the juvenile court system. Under her leadership, new standards were set in training social workers, and the University of Chicago became the center for social work in America. Her idea that the state needs to be more involved in social welfare took roots during the New Deal era.

The University of Chicago houses undergraduate students in Breckinridge House, which was named in her memory. There is also a "Sophie Day" that students celebrate every April 1.

Publications

- Breckinridge, Sophonisba. 1911. Chicago Housing Conditions: South Chicago at the gates of the steel mills. University of Chicago Press.

- Breckinridge, Sophonisba. [1912] 1970. The Delinquent Child and the Home. Arno Press. ISBN 040502438X

- Breckinridge, Sophonisba. 1920. A Summary of Juvenile-court Legislation in the United States. United States G.P.O.

- Breckinridge, Sophonisba. [1921] 2001. New Homes for Old. Transaction Publishers. ISBN 076580607X

- Breckinridge, Sophonisba. 1924. Family Welfare-work in a Metropolitan Community. University of Chicago Press.

- Breckinridge, Sophonisba. 1930. Separate Domicile for Married Women. Committee on the Legal Status of Women.

- Breckinridge, Sophonisba. 1931. Marriage and the Civic Rights of Women: Separate domicile and independent citizenship. The University of Chicago Press.

- Breckinridge, Sophonisba. 1931. Re-examination of the Work of Children's Courts. National Probation Association.

- Breckinridge, Sophonisba. [1933] 1972. Women in the Twentieth Century: A study of their political, social and economic activities. Ayer Co Pub. ISBN 040504450X

- Breckinridge, Sophonisba. [1934] 1972. The Family and the State. Ayer Co Pub. ISBN 0405038518

- Breckinridge, Sophonisba. 1969. Legal Tender: A study in English and American monetary history. Greenwood Press. ISBN 0837110793

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Addams, Jane. 1999. Twenty Years at Hull-House. Signet Classics. ISBN 0451527399

- Boxer, Marilyn J. 2001. When Women Ask the Questions: Creating Women's Studies in America. The Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0801868114

- Jabour, Anya. 2019. Sophonisba Breckinridge: Championing Women's Activism in Modern America. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0252084515

- Kleinberg, S. J. 2006. Widows and Orphans First: The Family Economy and Social Welfare Policy, 1880-1939. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 0252030206

- Lemons, Stanley J. 1990. The Woman Citizen: Social Feminism in the 1920's. University of Virginia Press. ISBN 0813913020

- Lenroot, Katharine F. 1948. Friend of Children and of the Children’s Bureau. Social Service Review. 22. 427-430.

- Muncy, Robyn. 1994. Creating a Female Dominion in American Reform, 1890-1935. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195089243

- Wright, Helen R. 1954. Three against Time: Edith and Grace Abbott and Sophonisba P. Breckinridge. University of Chicago Press.

External links

All links retrieved February 3, 2023.

- Sophonisba Breckinridge University of Chicago

- Sophonisba P. Breckinridge – Biography in Encyclopedia Britannica.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.