Speculum Humanae Salvationis

The Speculum Humanae Salvationis or Mirror of Human Salvation was a bestselling anonymous illustrated work of popular theology in the late Middle Ages, part of the genre of encyclopedic speculum literature, in this case concentrating on the medieval theory of typology, whereby the events of the Old Testament prefigured, or foretold, the events of the New Testament. The original version is in rhyming Latin verse, and contains a series of New Testament events each with three Old Testament ones that prefigure it.

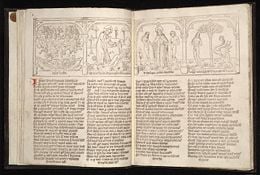

It is one of the most common books found as an illuminated manuscript, and also in early printing in both blockbook and incunabulum forms. During the Middle Ages, it was one of the most widely collected books of Christian popular piety, which fell in popularity following the Protestant Reformation and the ascendancy of vernacular Bible translations.

Contents

After a short "Prologue" (two pages) and Prohemium (four), both unillustrated, the first two chapters deal with the Creation, the Fall of Satan, the story of Adam and Eve and the Deluge in four pages. Then follow 40 more double-page chapters where a New Testament event is compared with three from the Old Testament, with four pictures each above a column of text. Usually each chapter occupies a two-page opening. The last three chapters cover the Seven Stations of the Cross, and the Seven Joys and Sorrows of Mary, at double this length. In all a complete standard version has 52 leaves, or 104 pages, and 192 illustrations (including a blank page at the beginning and end). The blockbook editions were much shorter, with 116 pictures, two to a woodblock.[1]

The writing of the text follows an exact scheme: 25 lines per column, with two columns per page, one under each miniature, so a hundred lines per standard chapter. Sometimes there are captions over the pictures as well, of varying content. Many copies reduced the original text, often by omitting the non-standard chapters at the beginning or end, whilst others boosted the content with calendars and commentaries, or extra illustrations.[2]

Dating and manuscript copies

The work originated between 1309 C.E., as a reference to the Pope being at Avignon indicates, and 1324 C.E., the date on two copies.[3] A preface, probably from the original manuscript, says the author will remain anonymous out of humility. He (or she) was almost certainly a cleric, and there is evidence he was a Dominican.[4] Ludolph of Saxony is a leading candidate for authorship, and Vincent of Beauvais has also been suggested.[5]

The first versions are naturally in illuminated manuscript form, and in Latin. Many copies were made, and several hundred still survive (over 350 in Latin alone), often in translations into different vernacular languages; at least four different translations into French were made, and at least two into English. There were also translations into German, Dutch, Spanish and Czech.[6]

Manuscript versions covered the whole range of the manuscript market: some are lavishly and expensively decorated, for a de luxe market, whilst in many the illustrations are simple, and without color. In particular, superb Flemish editions were produced in the fifteenth century for Philip the Good and other wealthy bibliophiles. The Speculum is probably the most popular title in this particular market of illustrated popular theology, competing especially with the Biblia pauperum and the Ars moriendi for the accolade.

Printed editions

In the fifteenth century, with the advent of printing, the work then appeared in four blockbook editions, two Latin and two in Dutch, and then in 16 incunabulum editions by 1500. The blockbooks combine hand-rubbed woodcut pages with text pages printed in movable type. Further eccentricities include a run of 20 pages in one edition which are text cut as a woodcut, based on tracings of pages from another edition printed with movable type. Though the circumstances of production of these editions are unknown, two of the editions are in Dutch and the Netherlands was probably the centre of production, as with most blockbooks.[7] The Prohemium may have been sold separately as a pamphlet, as one version speaks of the usefulness of it for "poor preachers who cannot afford the entire book".[8]

The incunabulum editions, from 11 different presses, mostly, but not all, printed their woodcut illustrations in the printing press with the text. Some seem to have been printed in two sessions for texts and images. Günther Zainer of Augsburg, a specialist in popular illustrated works, produced the first one in 1473, in Latin and German, and with a metrical summary newly added for each chapter; this is considered an especially beautiful edition.[9] Further incunabulum editions include Latin, German, French, Spanish and Dutch versions, and it was the first illustrated book printed in both Switzerland, at Basel, and France, at Lyon, which used the Basel picture blocks, later also used in Spain.[10] A Speyer edition has woodcuts whose design has been attributed to the Master of the Housebook.[11] In addition, the first of the somewhat legendary editions supposedly produced by Laurens Janszoon Coster, working earlier than Johannes Gutenberg, was a Speculum. Even if the Coster story is ignored, the work seems to have been the first printed in the Netherlands, probably in the early 1470s.[12] Editions continued to be printed until the Reformation, which changed the nature of religious devotion on both sides of the Catholic/Protestant divide, and made the Speculum seem outdated.

Iconographic influence

The images in the Speculum were treated in many different styles and media over the course of the two centuries of its popularity, but generally the essentials of the compositions remained fairly stable, partly because most images had to retain their correspondence with their opposite number, and often the figures were posed to highlight these correspondences. Many works of art in other media can be seen to be derived from the illustrations; it was for example, the evident source for depictions for the Vision of Augustus in Rogier van der Weyden's Bladelin Altarpiece and other Early Netherlandish works.[13] In particular the work was used as a pattern-book for stained glass, but also for tapestries and sculpture.

Notes

- ↑ Arthur M. Hind, An Introduction to a History of Woodcut (Houghton Mifflin, (1935), reprinted New York: Dover Publications, 1963, ISBN 0486209520), 245.

- ↑ Adrian Wilson and Joyce Lancaster Wilson, A Medieval Mirror, Speculum Humanae Salvationis 1324-1500. (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1984), 27-28.

- ↑ Wilson & Wilson, 26.

- ↑ Wilson & Wilson, 10.

- ↑ Wilson & Wilson, 26-27.

- ↑ Wilson & Wilson, 10; Hind, 602

- ↑ Wilson & Wilson, 11; Hind, 247.

- ↑ Wilson & Wilson, 120.

- ↑ Wilson & Wilson, 207.

- ↑ A. Hyatt Mayor, Prints and People (Metropolitan Museum of Art/Princeton, 1971, nos.32, 33, ISBN 0691003262).

- ↑ Wilson & Wilson, 208.

- ↑ Wilson & Wilson, 111 ff.

- ↑ Wilson & Wilson, 28.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Carruthers, Mary, and Jan M. Ziolkowski. The Medieval Craft of Memory: An Anthology of Texts and Pictures (Material Texts). University of Pennsylvania Press, 2003. ISBN 0812218817.

- Henry, Avril. The Mirour of Mans Saluacioun(e): A Middle English Translation of Speculum Humanae Salvationis: A Critical Edition of the Fifteenth-Century Manuscript. Scholar Press, 1986. ISBN 0859677168.

- Hind, Arthur M. An Introduction to a History of Woodcut. Houghton Mifflin Co. (1935), reprinted New York: Dover Publications, 1963. ISBN 0486209520.

- Mayor, A. Hyatt. Prints and People Metropolitan Museum of Art/Princeton, 1971, nos.32 33. ISBN 0691003262.

- Peters, E. and Bert Cardon. Manuscripts of the Speculum Humanae Salvationis in the Southern Netherlands (C.1410-C.1470): A Contribution to the Study of the 15th Century Book. David Brown, 1998. ISBN 9068317733.

- Smeltz, John W., and Albert C. Labriola. The Mirror of Salvation [Speculum Humanae Salvationis]: An Edition of British Library Blockbook G.11784. Duquesne University Press, 2002. ISBN 0820703230.

- Wilson, Adrian, and Joyce Lancaster Wilson. A Medieval Mirror, Speculum Humanae Salvationis 1324-1500. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1984.

External links

All links retrieved February 7, 2023.

- Miroir de l'humaine salvation A lavish Flemish manuscript (Bruges, 1455) from the Hunterian Library, Glasgow.

- Some images from French manuscripts. Note consistency of images between Lyon and Marseilles.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.