Takla Makan Desert

The Takla Makan (also Taklamakan or Taklimakan) is China's largest desert, and is considered to be the second largest shifting sand desert in the entire world. Lying in the large Tarim Basin of the Uygur Autonomous Region of Xinjiang in northwest China, the desert wasteland encompasses a total area of over 123,550 square miles (320,000 square km). The desert area extends about 600 miles (960 km) from west to east, and has a maximum width of some 260 miles (420 km). The eastern and northern areas of the desert reach elevations of 2,600 to 3,300 feet (800 to 1,000 m), while 3,900 to 4,900 feet (1,200 to 1,500 m) above sea level are realized in the western and southern sections.

The constantly shifting sands and extreme weather conditions of the region has earned the desert the foreboding nickname of "The Sea of Death." While the nickname for the desert reflects the harsh conditions of life on the sand, more accurate etymological traces of the name translate Takla Makan as something closer to "unreturnable."

Geography

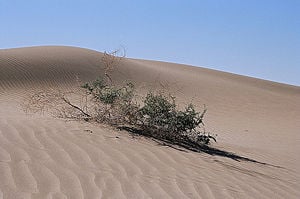

The Takla Makan is distinguished by its constantly moving sand dunes, some of which reach heights of over 109 yards. In extremely rare cases, sand dunes in the Takla Makan have been measured at over 328 yards. However, the smaller dunes are far more common as the constant winds in the desert keep the sand moving. Some estimates state that the dunes can move as much as 164 yards each year. While the perpetual movement of the sand contributes to its wild beauty, the constant movement hinders vegetation growth and threatens local populations. Particularly threatened are the rare oases in the Takla Makan, which are constantly in danger of being consumed by the shifting sands. In recent years a movement has been undertaken by the Chinese government to plant a series of wind resistant plants in areas of high erosion. The planting had slightly improved the livelihood of surrounding population, however, their long term effects remain to be seen.

While the man–made windbreaks in the area may prove slightly beneficial, much of the harsh conditions in the area are simply a result of natural geographic features. The Takla Makan lies within a large desert basin, fringed on all sides by protective mountain rages. The mountain ring, formed by the Tien Shan Mountains to the north, the Kunlun Mountains to the southwest and the Altun Mountains in the south, forms a wind tunnel preventing the winds from easily escaping the desert.

As is common in all desert environments, usable water is scarce. The only rivers that flow into the Takla Mahan are the White Jade River and the Yarkant River, neither of which carry enough to support the population. Precipitation in the region is remarkably low, ranging from 1.5 inches per year in the western portions of the desert to .04 inches annually in the east. Hikers and other visitors in the region are often dissuaded from crossing the desert due to the sheer amounts of water that must be carried in order to stay alive. If travelers are lucky, however, they can avoid extreme drought by moving between the desert oases towns of Kashgar, Yarkand, and Khotan (Hetian) in the South-West, Kuqa and Turfan in the North, and Loulan and Dunhuang in the East.

Until recent times, the near complete lack of vegetation in the region has marked the desert as a poor source of natural resources. However,in recent years the Takla Makan has gained attention for its rich natural reserves of oil, oil gas, and groundwater. In low basins the groundwater lies only 10-15 feet below the sandy surface. However, the underwater groundwater is often hard to access due to the moving sand dunes that can easily cover wells.

Capitalizing on another natural resource, the area has become a major source for oil and petroleum products. The rapid proliferation of oil fields in the region drew attention to flaws of cross–desert transportation. In 1995, a desert road was opened in the Takla Makan to increase the possible utilization of the area for industry. Another road is currently under construction.

Nearly the entire desert is devoid of vegetation. Some sand dune depressions may contain thin thickets of tamarisk, nitre bushes, and reeds. The edges of the desert area, near the river valleys, contain the same plants as well as Turanga poplar, oleaster, camel thorn, members of the Zygophyllaceae (caltrop) family, and saltworts.

Herds of gazelles can be found in some open areas near water and vegetation. Wild boars, wolves and foxes can also be found. The Siberian deer and wild camels can occasionally be seen. The dunes contains large numbers of rabbits, mice and gerbils. Hedgehogs and bats are common. The common birds of the Takla Makan are tufted larks and the Tarim jay.

History

The earliest known inhabitants of the Takla Makan were herdsmen who had followed their livestock from grazing grounds in Eastern Europe. The discovery of well preserved 4,000 year old mummies in the region document the presence of these wandering herdsmen in the desert as early as 2,000 B.C.E. Many of the mummies that have been found exhibit Caucasian hair color and were wearing European twill fabrics. The archaeologists responsible for finding these mummies hope to explain the early links between European and Asian cultures.

One explanation for the abundance of Caucasion burial remains is the location of the Takla Makan along the Silk Road. As a trade route in the early half of the first century B.C.E., the Silk Road linked Central Asia to the Greek and Roman Empires in the west. The name Silk Road however, is a bit of a misnomer, as more than simply silk was exchanged. Other main staples of this route included gold and ivory, as well as exotic plants and animals. In addition, the Silk Road had many tributary paths, only a small handful of which crossed the Takla Makan.

The Silk Road soon became a major conduit for the exchange of religious concepts and ideals between the continents. All along the Takla Makan small grottoes were developed, where individuals seeking a simpler life could retreat to the foothills of the mountains. Often financed by rich merchants seeking the prayers of the Holy for the after life, the grottoes of the Takla Makan were richly decorated with murals and other artistic pieces. While religious grottoes can be found all along the Silk Road, the enclaves in the foothills of the Takla Makan are widely considered to be the most well preserved and artistic examples.

As the Silk Road began to decline in the early 900s C.E., fewer visitors braved the harsh winds and inhospitable terrain of the Takla Makan. Grotto building and artistic development in the region thus began to decline. The final blow for the Silk Road culture of the Takla Makan came when warring states began to plunder the desert caravans. With no security for a safe passage, the Takla Makan entered a period of economic decline with the decline of supply of merchants passing through the region. The fourteenth century saw a rise of Islam in the region, the final blow for the grotto art movement. Under Islam, the human is not represented in painted image, a fact which stopped the mural painting in the Takla Mahan communities. Many of the original grotto paintings were destroyed during this period.

Since the 1950s, the Chinese government has been encouraging its population to settle in the Takla Makan. However, the land in the region is too poor to support sustained agriculture and very few have chosen to make it their home. To this day, the Takla Hakan has no permanent population. The individuals who do enter into the "Sea of Death" are either adventurers seeking to test their mettle against one of the world's most challenging landscapes or hunters hoping that periodic visits will prove profitable.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Jarring, Gunnar. 1997. The toponym Takla-makan. Turkic Languages. Vol. 1.

- Hopkirk, Peter. 1984. Foreign devils on the Silk Road: the search for the lost cities and treasures of Chinese Central Asia. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press. ISBN 0870234358 and ISBN 9780870234354

- Hopkirk, Peter. 1994. The great game: the struggle for empire in central Asia. Kodansha globe. New York: Kodansha International. ISBN 1568360223 and ISBN 9781568360225

- Graceffo, Antonio. 2005. The desert of death on three wheels. Columbus, Ohio: Gom Press. ISBN 1932966374 and ISBN 9781932966374

- Tourism in the Takla Makan. TravelChinaGuide.com, 2007. Retrieved October 22, 2007.

- Takla Makan Desert. Encyclopedia Britannica Online. Retrieved October 22, 2007.

- Wild, Oliver. 1992. The Silk Road. School of Physical Sciences, UCIrvine. Retrieved October 22, 2007.

External links

All links retrieved February 26, 2023.

- Takla Makan Desert – TravelChinaGuide.

- The Most Important Findings of Niya in Taklamakan – Silk Road Foundation.

- The Takla Makan Mummies – NOVA, PBS Online.

- Mysterious Mummies of China – NOVA, PBS Online.

| Deserts |

|---|

| Ad-Dahna | Alvord | Arabian | Aral Karakum | Atacama | Baja California | Barsuki | Betpak-Dala | Chalbi | Chihuahuan | Dasht-e Kavir | Dasht-e Lut | Dasht-e Margoh | Dasht-e Naomid | Gibson | Gobi | Great Basin | Great Sandy Desert | Great Victoria Desert | Kalahari | Karakum | Kyzylkum | Little Sandy Desert | Mojave | Namib | Nefud | Negev | Nubian | Ordos | Owyhee | Qaidam | Registan | Rub' al Khali | Ryn-Peski | Sahara | Saryesik-Atyrau | Sechura | Simpson | Sonoran | Strzelecki | Syrian | Taklamakan | Tanami | Thar | Tihamah | Ustyurt |

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.