Thomas Chatterton

| |

| Born: | November 20 1752 Bristol, England |

|---|---|

| Died: | August 24 1770 (aged 17) Holborn, England |

| Occupation(s): | Poet, forger |

Thomas Chatterton (November 20, 1752 â August 24, 1770) was an English poet and forger of pseudo-medieval poetry. Committing suicide by arsenic rather than die of starvation at the young age of 17, he served as an icon of unacknowledged genius for the Romantics. Chatterton never lived to see an edition of his poems published or see the monument his well-wishers had placed outside St Mary Redcliffe in Bristol, England. His work, however, has been acclaimed posthumously.

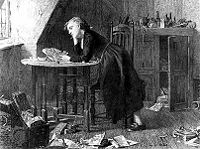

Chatterton's genius and his tragic death are commemorated by many major poets and authors of the romantic style. Percy Bysshe Shelley in Adonais, by William Wordsworth in Resolution and Independence, by Samuel Taylor Coleridge in A Monody on the Death of Chatterton, by Dante Gabriel Rossetti in Five English Poets, by Henry Wallis in his painting The Death of Chatterton, and John Keats inscribed Endymion "to the memory of Thomas Chatterton."

Early Life

Chatterton was born at Bristol where the office of sexton of St. Mary Redcliffe, a parish church in England, had been held for nearly two centuries by the Chatterton family. Throughout his brief life it was held by his uncle, Richard Phillips. His father, Thomas Chatterton, was a musical genius, a poet, a numismatist, and a dabbler in the occult. He had been a sub-chanter at Bristol Cathedral and master of the Pyle Street free school, near Redcliffe church. The elder Chaterton died four months before his son's birth. Chatterton's mother took in sewing and ornamental needlework and established a girls' school. Chatterton attended this school until his eighth year, when he was admitted to Colston's Charity.

From his earliest years he was liable to fits of abstraction, sitting for hours in what seemed like a trance, or crying for no reason. His lonely circumstances helped foster his natural reserve, and to create the love of mystery which exercised such an influence on the development of his genius. When he was six, his mother began to recognize his capacity; at eight he was so eager for books that he would read and write all day long if undisturbed; by the age of eleven, he had become a contributor to Felix Farley's Bristol Journal.

Works

The first of his literary mysteries, the dialogue of "Elinoure and Juga," was written before he was twelve, and he showed it to the usher at Colston's hospital, Thomas Phillips. Three of Chatterton's companions are named as youths whom Phillips' taste for poetry stimulated to rivalry. Chatterton told no one about his own more daring literary adventures. His little pocket-money was spent on borrowing books from a circulating library. He ingratiated himself with book collectors, in order to obtain access to Weever, Dugdale and Collins, as well as to Thomas Speght's edition of Chaucer, Spenser and other books.

Chatterton also used the pseudonym Thomas Rowley for poetry and history. Chatterton's "Rowleian" jargon appears to have been chiefly the result of the study of John Kersey's Dictionarium Anglo-Britannicum. His holidays were mostly spent at his mother's house, and much of them in the favorite retreat of his attic study there. He had already conceived the romance of Thomas Rowley, an imaginary monk of the fifteenth century, and lived for the most part in an ideal world of his own, in the reign of Edward IV, when Master William Canyngeâfamiliar to him among the recumbent effigies in Redcliffe church&mdashlstill ruled in Bristol's civic chair. Canynge is represented as an enlightened patron of literature, and Rowley's dramatic interludes were written for studies.

In 1769 Chatterton sent Rowley's History of England, allegedly by Rowley, to Horace Walpole, who was briefly taken in. Chatterton now turned his attention to periodical literature and politics, and exchanged Felix Farley's Bristol Journal for the Town and County Magazine and other London periodicals. Assuming the vein of Juniusâthen in the full blaze of his triumphâhe turned, his pen against the Duke of Grafton, the Earl of Bute, and Augusta of Saxe-Gotha, the Princess of Wales.

Last days

He had just dispatched one of his political diatribes to the Middlesex Journal, when he sat down on Easter Eve, April 17, 1770, and penned his "Last Will and Testament," a strange satirical compound of jest and earnest, in which he intimated his intention of ending his life the following evening. Among his satirical bequests to the school personnel, were his "humility" to the Reverend Mr Camplin, his "religion" to Dean Barton, and his "modesty" along with his "prosody and grammar" to Mr Burgum, he leaves "to Bristol all his spirit and disinterestedness, parcels of goods unknown on its quay since the days of Canynge and Rowley." In more genuine earnestness he recalls the name of Michael Clayfield, a friend to whom he owed intelligent sympathy. The will was probably purposely prepared in order to frighten his master into letting him leave. It had the desired effect. Lambert canceled his indentures, his friends and acquaintances donated money, and he went to London.

Chatterton was already known to the readers of the Middlesex Journal as a rival of Junius, under the nom de plume of Decimus. He had also been a contributor to Hamilton's Town and County Magazine, and speedily found access to the Freeholder's Magazine, another political miscellany supportive of John Wilkes and liberty. His contributions were accepted, but the editors paid little or nothing for them.

He wrote hopefully to his mother and sister, and spent his first earnings in buying gifts for them. His pride and ambition were gratified by the promises and interested flattery of editors and political adventurers; Wilkes himself had noted his trenchant style "and expressed a desire to know the author"; and Lord Mayor William Beckford graciously acknowledged a political address of his, and greeted him "as politely as a citizen could." He was abstemious and diligence was great. He could assume the style of Junius or Tobias Smollett, reproduce the satiric bitterness of Churchill, parody Macpherson's Ossian, or write in the manner of Pope, or with the polished grace of Thomas Gray and William Collins.

He wrote political letters, eclogues, lyrics, operas and satires, both in prose and verse. In June 1770âafter nine weeks in Londonâhe moved from Shoreditch, where he had lodged with a relative, to an attic in Brook Street, Holborn. He was still short of money; and now state prosecutions of the press rendered letters in the Junius vein no longer admissible, and threw him back on the lighter resources of his pen. In Shoreditch, he had only shared a room; but now, for the first time, he enjoyed uninterrupted solitude. His bed-fellow at Mr Walmsley's, Shoreditch, noted that much of the night was spent by him in writing; and now he could write all night. The romance of his earlier years revived, and he transcribed from an imaginary parchment of the old priest Rowley his "Excelente Balade of Charitie." This fine poem, perversely disguised in archaic language, he sent to the editor of the Town and County Magazine, and had it rejected.

Already failure and starvation stared Chatterton in the face. Mr. Cross, a neighboring apothecary, repeatedly invited him to join him at dinner or supper; but he refused. His landlady also, suspecting his necessity, pressed him to share her dinner, but in vain. "She knew," as she afterwards said, "that he had not eaten anything for two or three days." But he assured her that he was not hungry. The note of his actual receipts, found in his pocket-book after his death, shows that Hamilton, Fell and other editors who had been so liberal in flattery, had paid him at the rate of a shilling for an article, and less than eightpence each for his songs; much which had been accepted was held in reserve and still unpaid.

According to his foster-mother, he had wished to study medicine with Barrett, and in his desperation he wrote to Barrett for a letter to help him to an opening as a surgeon's assistant on board an African trader. On August 24, 1770, he retired for the last time to his attic in Brook Street, carrying with him the arsenic which he drank, after tearing into fragments whatever literary remains were at hand. He was only seventeen years and nine months old; but the best of his numerous productions, in prose and verse, seem very mature.

Posthumous recognition

The death of Chatterton attracted little notice at the time; for the few who then entertained any appreciative estimate of the Rowley poems regarded him as their mere transcriber. He was interred in a burying-ground attached to Shoe Lane Workhouse, in the parish of St Andrew's, Holborn, which has since been converted into a site for Farringdon Market. There is a discredited story that the body of the poet was recovered, and secretly buried by his uncle, Richard Phillips, in Redcliffe Churchyard. There a monument has since been erected to his memory, with the appropriate inscription, borrowed from his "Will," and so supplied by the poet's own pen. "To the memory of Thomas Chatterton. Reader! judge not. If thou art a Christian, believe that he shall be judged by a Superior Power. To that Power only is he now answerable."

It was after Chatterton's death that the controversy over his work began. Poems supposed to have been written at Bristol by Thomas Rowley and others, in the Fifteenth Century (1777) was edited by Thomas Tyrwhitt, a Chaucerian scholar who believed them genuine medieval works. However, the appendix to the following year's edition recognizes that they were probably Chatterton's own work. Thomas Warton, in his History of English Poetry (1778) included Rowley among fifteenth century poets, but apparently did not believe in the antiquity of the poems. In 1782 a new edition of Rowley's poems appeared, with a "Commentary, in which the antiquity of them is considered and defended," by Jeremiah Milles, dean of Exeter.

Legacy

Chatterton's genius and his tragic death are commemorated by Shelley in Adonais (though its main emphasis is the commemoration of Keats), by Wordsworth in "Resolution and Independence," by Coleridge in "A Monody on the Death of Chatterton," by Dante Gabriel Rossetti in "Five English Poets," by Henry Wallis in his painting "The Death of Chatterton," and John Keats inscribed Endymion "to the memory of Thomas Chatterton." Alfred de Vigny's drama of Chatterton gives an altogether fictitious account of the poet. Herbert Croft, in his Love and Madness, interpolated a long and valuable account of Chatterton, giving many of the poet's letters, and much information obtained from his family and friends (pp. 125-244, letter Ii.). Peter Ackroyd's 1987 novel Chatterton was an acclaimed literary re-telling of the poet's story, giving emphasis to the philosophical and spiritual implications of forgery.

Chatterton has attracted operatic treatment a number of times throughout history, notably Ruggiero Leoncavallo's largely unsuccessful 2 Act "Chatterton"; The German composer Matthias Pinscher's modernistic "Thomas Chatterton"; and Australian composer Matthew Dewey's lyrical yet dramatically intricate one-man mythography entitled "The Death of Thomas Chatterton."

There is a collection of "Chattertoniana" in the British Museum, consisting of separate works by Chatterton, newspaper cuttings, articles, dealing with the Rowley controversy and other subjects, with manuscript notes by Joseph Haslewood, and several autograph letters.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Ackroyd, Peter. Chatterton. New York: Grove Press, 1988. ISBN 9780802100412

- Chatterton, Thomas, Walter W. Skeat, and Edward Bell. The Poetical Works of Thomas Chatterton. New York: AMS Press, 1968. OCLC 2616390

- Groom, Nick. Thomas Chatterton and Romantic Culture. London: Macmillan, 1999. OCLC 41880324

- Meyerstein, Edward Harry William. A Life of Thomas Chatterton. New York: Russell & Russell, 1972. OCLC 333467

- Nevill, John Cranstoun. Thomas Chatterton. Port Washington, N.Y.: Kennikat Press, 1970. ISBN 9780804608459

External links

All links retrieved April 30, 2023.

- Works by Thomas Chatterton. Project Gutenberg.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.