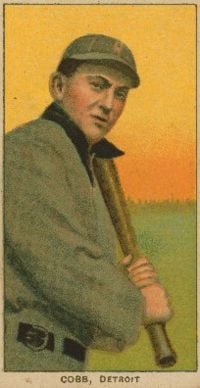

Ty Cobb

Ty Cobb

| |

| Personal Info | |

|---|---|

| Birth | December 18, 1886, Narrows, Georgia |

| Death: | July 17, 1961, Atlanta, Georgia |

| Professional Career | |

| Debut | August 30, 1905, Detroit Tigers |

| Team(s) | As Player Detroit Tigers (1905–1926) |

| HOF induction: | 1936 |

| Career Highlights | |

| |

Tyrus Raymond "Ty" Cobb (December 18, 1886 – July 17, 1961), nicknamed "The Georgia Peach," was a Hall of Fame baseball player. When he retired in 1928, he was the holder of 43 major league records.[1] Cobb also received the most votes of any player on the 1936 inaugural Hall of Fame ballot.[2]

Cobb holds the records for highest major-league career batting average of .366 and most career batting titles at 12. He led the American League in stolen bases six times, with his 1915 record of 96 stolen bases lasting until 1962. Cobb also held for decades the record for most career major league hits (4,191), which was broken by Pete Rose, and the most career runs (2,245), which was broken by Rickey Henderson.[3] Upon his death in 1961, the New York Times editorialized, "Let it be said that Cobb was the greatest of all ballplayers."

The greatest star during his playing prime before the emergence of Babe Ruth, Cobb's legacy as an athlete has sometimes been overshadowed by his surly temperament, racist attitudes, and aggressive on-field reputation, which was described by the Detroit Free Press as "daring to the point of dementia."[4] So great was his fellow players' disdain toward Cobb, that when the legendary ballplayer died in 1961, only three representatives from all of baseball attended his funeral in person, although numerous messages of condolence were received from others involved in the sport. Yet some connoisseurs of the national pastime claim that Cobb played the game the way it should be played—with an all-out tenacity and a driving passion to win.

Early life and baseball career

Ty Cobb was born in Narrows, Georgia, as the first of three children to Amanda Chitwood Cobb and William Herschel Cobb. His early career was hardly illustrious. Ty spent his first years in baseball as a member of the Royston Rompers, the semi-pro Royston Red, and the Augusta Tourists of the Sally League. However, the Tourists cut Cobb two days into the season. He then went to try out for the Anniston Steelers of the semi-pro Tennessee–Alabama League, with his father's stern admonition still ringing in his ears: "Don't come home a failure."

Cobb promoted himself by sending several postcards to Grantland Rice, the sports editor of the Atlanta Journal under several different aliases. Eventually, Rice wrote a small note in the journal that a "young fellow named Cobb seems to be showing an unusual lot of talent."[5] After about three months, Ty returned to the Tourists. He finished the season hitting .237 in 35 games. In 1905, the Tourists' management sold Cobb to the American League's Detroit Tigers for $750.[4]

On August 8, 1905, Ty's father was tragically shot to death by Ty's mother. William Cobb suspected his wife of infidelity and was sneaking past his own bedroom window to catch her in the act. She only saw the silhouette of what she presumed to be an intruder, and shot twice, killing William Cobb.[6] Cobb's father would never witness his son's major league success.

Major League Career

The early years

Cobb played center field for the Detroit Tigers. On August 30, 1905, in his first major league at-bat, Cobb doubled off the New York Highlanders's Jack Chesbro. That season, Cobb managed to bat only .240 in 41 games. Nevertheless, he showed enough promise as a rookie for the Tigers to give him a lucrative $1,500 contract for 1906.

Although rookie hazing was customary, Cobb could not endure it in good humor, and he soon became alienated from his teammates. He later attributed his hostile temperament to this experience: "These old-timers turned me into a snarling wildcat."[7]

The following year (1906) he became the Tigers' full-time center fielder and hit .316 in 98 games. He would never hit below that mark again. Cobb, firmly entrenched in center field, led the Tigers to three consecutive American League pennants from 1907 to 1909. Detroit would lose each World Series, however, with Cobb's post-season numbers falling much below his career standard. In one notable 1907 game, Cobb reached first, stole second, stole third, and then stole home on consecutive attempts. He finished that season with a league-high .350 batting average, 212 hits, 49, steals and 119 runs batted in (RBI).

Despite great success on the field, Cobb was no stranger to controversy off it. At spring training in 1907, he got in a fight with a black groundskeeper who he thought was drunk and had called him the wrong name. When the groundskeeper’s wife started yelling at Cobb, Cobb started choking her.[6]

In September 1907, Cobb began a relationship with the Coca-Cola Company that would last the remainder of his life. By the time he died, he owned three bottling plants and over 20,000 shares of stock. He was also a celebrity spokesman for the product.

The following season, the Tigers bested the Chicago White Sox for the pennant. Cobb again won the batting title; he hit .324 that year.

Despite another loss in the World Series, Cobb had something to celebrate. In August 1908, he married Charlotte "Charlie" Marion Lombard, the daughter of prominent Augustan Roswell Lombard.

The Tigers won the American League pennant again in 1909. During the World Series, Cobb stole home in the second game, igniting a three-run rally, but that was the high point for Cobb. He ended batting a lowly .231 in this, his last World Series, as the Tigers lost in seven games. Although he performed poorly in the post-season, Cobb won the Triple Crown by hitting .377 with 107 RBI and 9 home runs—all inside-the-park home runs. Cobb thus became the only player of the modern era to lead his league in home runs in a given season without hitting a ball over the fence.

The 1910 Chalmers Award controversy

In 1910, Cobb and Nap Lajoie were neck-and-neck for the American League batting title. Cobb was ahead by a slight margin going into the last day of the season. The prize for the winner of the title was a Chalmers automobile.

Cobb sat out the game to preserve his average. Lajoie, whose team was playing the St. Louis Browns, notched eight hits in a doubleheader. Six of those hits were bunt singles that fell in front of the third baseman. It turned out that Browns’ manager, Jack O'Connor, had ordered third baseman Red Corriden to play deep, on the outfield grass, so as to allow the popular Lajoie to win the title. The Browns disliked Cobb and did not want to see him win the title. When a “ninth” hit by Lajoie was ruled a fielder’s choice, Browns’ coach Henry Howell attempted to bribe the scorekeeper to change the ruling to a hit. The scorekeeper refused, and a few days later, AL president Ban Johnson declared all batting averages official, with Cobb hanging on to win, .384944 to .384084. O’Connor and Howell were fired after news about their scheming got around. They would never work in organized baseball again.[6]

The 1911 season and 1912 fight

Cobb was having a typically fine year in 1911, which included a 40-game hitting streak. Still, “Shoeless” Joe Jackson had a .009 point lead on him in batting average. Near the end of the season, Cobb’s Tigers had a long series against Jackson and the Cleveland Naps. Fellow Southerners, Cobb and Jackson were personally friendly both on and off the field. However, Cobb suddenly ignored Jackson whenever Jackson said anything to him. When Jackson persisted, Cobb snapped angrily at Jackson, making him wonder what he could have done to enrage Cobb. As soon as the series was over, Cobb unexpectedly greeted Jackson and wished him well. Cobb felt that it was these mind games that caused Jackson to "fall off" to a final average of .408, while Cobb himself finished with a .420 average.[8]

Cobb led the AL that year in numerous categories besides batting average, including hits (248), runs scored (147), RBIs (127), stolen bases (83), doubles (47), triples (24), and slugging average (.621). The only major offensive category in which Cobb did not finish first was home runs, where Frank Baker surpassed him 11-8. Cobb's dominance at the plate is suggested by the following statistic: he struck out swinging only twice during the entire 1911 season. He was voted the AL MVP by the Baseball Writers Association of America.

The game that may best illustrate Cobb's unique combination of skills and attributes occurred on May 12, 1911. Playing against the New York Yankees, Cobb scored a run from first base on a single to right field, then scored another run from second base on a wild pitch. In the seventh inning, he tied the game with a 2-run double. The Yankee catcher began vociferously arguing the call with the umpire, going on at such length that the other Yankee infielders gathered nearby to watch. Realizing that no one on the Yankees had called time, Cobb strolled unobserved to third base, and then casually walked towards home plate as if to get a better view of the argument. He then suddenly slid into home plate for the game's winning run.[8]

On May 15, 1912, Cobb assaulted Claude Lueker, a heckler, in the stands in New York. Lueker and Cobb traded insults with each other throughout the first three innings, and the situation climaxed when Lueker called Cobb a "half-nigger." Cobb then climbed into the stands and attacked the handicapped Lueker, who due to an industrial accident had lost all of one hand and three fingers on his other hand. When onlookers shouted at Cobb to stop because the man had no hands, Cobb reportedly replied, "I don't care if he has no feet." The league suspended him, and his teammates, though not fond of Cobb, went on strike to protest the suspension prior to the May 18 game in Philadelphia.[6]

1915-1921

In 1915, Cobb set the single season steals record when he stole 96 bases. That record stood until Maury Wills broke it in 1962. Cobb’s streak of five batting titles ended the following year when he finished second (.371) to Tris Speaker’s .386.

In 1917, Cobb hit in 35 consecutive games; he remains the only player with two 35-game hitting streaks to his credit (he also had a 40-game hitting streak in 1911). Over his career, Cobb had six hitting streaks of at least 20 games, second only to Pete Rose's seven.

By 1920, Babe Ruth had established himself as a power hitter, something Cobb was not. When Cobb and the Tigers showed up in New York to play the Yankees for the first time that season, writers billed it as a showdown between two stars of competing styles of play. Ruth hit two homers and a triple during the series while Cobb got only one single in the entire series.

As Ruth's popularity grew, Cobb became increasingly hostile toward him. Cobb saw Ruth not only as a threat to his style of play, but also to his style of life. While Cobb preached ascetic self-denial, Ruth gorged on hot dogs, beer, and women. Perhaps what angered him the most about Ruth was that despite Ruth's total disregard for his physical conditioning and traditional baseball, he was still an overwhelming success and brought fans to the ballparks in record numbers to see him break Cobb's own records.

After enduring several years of seeing his fame and notoriety usurped by Ruth, Cobb decided that he was going to show that swinging for the fences was no challenge for a top hitter. On May 5 1925, Cobb began a two-game hitting spree that topped any even Ruth had unleashed. He was sitting in the dugout talking to a reporter and told him that, for the first time in his career, he was going to swing for the fences. That day, Cobb went 6 for 6, with two singles, a double, and three home runs. His 16 total bases set a new AL record. The next day he had three more hits, two of which were home runs. A single his first time up gave him 9 consecutive hits over three games. His five homers in two games tied the record set by Cap Anson of the old Chicago NL team in 1884. Cobb wanted to show that he could hit home runs when he wanted, but simply chose not to do so. At the end of the series, 38-year-old Cobb had gone 12 for 19 with 29 total bases, and then went happily back to bunting and hitting-and-running. For his part, Ruth's attitude was that "I could have had a lifetime .600 average, but I would have had to hit them singles. The people were paying to see me hit home runs."

On August 19 1921, in the second game of a doubleheader against the Boston Red Sox, Cobb collected his 3,000th hit.

Cobb as player/manager

For the 1921 season, Frank Navin, the Detroit Tigers owner, signed Cobb to take over for Hughie Jennings as manager. Cobb signed the deal on his 34th birthday for $32,500. Universally disliked (even by the members of his own team) but a legendary player, Cobb's management style left a lot to be desired. He expected as much from his players as he gave, and most of the men did not meet his standard.

The closest he came as a manager to winning the pennant race was in 1924, when the Tigers finished in third place, six games behind the pennant-winning Washington Senators. The Tigers had finished second in 1922, but were 16 games behind the Yankees.

Cobb blamed his lackluster managerial record (479–444) on Navin, who was arguably an even bigger skinflint than Cobb. Navin passed up a number of quality players that Cobb wanted to add to the team. In fact, Navin had saved money by hiring Cobb to manage the team.

Also in 1922, Cobb tied a batting record set by Wee Willie Keeler, with four five-hit games. This has since been matched by Stan Musial, Tony Gwynn, and Ichiro Suzuki.

At the end of 1925, Cobb was once again embroiled in a batting title race, this time with one of his teammates, Harry Heilmann. In a doubleheader against the St. Louis Browns on October 4, Heilmann got six hits, leading the Tigers to a sweep of the doubleheader and beating Cobb for the batting crown, .393 to .389. Cobb and Browns’ manager George Sisler each pitched in the final game. Cobb pitched a perfect inning.

Move to Philadelphia

Cobb finally called it quits after a 22-year career as a Tiger in November 1926. He announced his retirement and headed home to Augusta, Georgia. Shortly thereafter, Tris Speaker also retired as player-manager of the Cleveland team. The retirement of two great players at the same time sparked some interest, and it turned out that the two were coerced into retirement because of allegations of game-fixing brought about by Dutch Leonard, a former pitcher of Cobb's Detroit Tigers.

Leonard was unable to convince either Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis or the public that the two had done anything for which they deserved to be kicked out of baseball. Landis allowed both Cobb and Speaker to return to their original teams, but each team let them know that they were free agents and could sign with whomever they wished. Cobb signed with the Philadelphia Athletics. Speaker then joined Cobb in Philadelphia for the 1928 season. Cobb reportedly said he came back only to seek vindication and so that he could leave baseball on his own terms.

Cobb played regularly in 1927 for a young and talented team that finished second to one of the greatest teams of all time, the 1927 New York Yankees. He returned to Detroit on May 11, 1927. Cobb doubled in his first at bat, to the cheers of Tiger fans. On July 18, 1927, Cobb became the first player to enter the 4,000-hit-club when he doubled off former teammate Sam Gibson of the Detroit Tigers at Navin Field.

Cobb returned again in 1928. He played less frequently due to his age and the blossoming abilities of the young A's, who were again in a pennant race with the Yankees. It was against those Yankees in September that Cobb had his last at-bat, a weak pop-up behind third base. He then announced his retirement, effective at the end of the season. Ironically, had he stuck with the A's in some capacity for one more year, he might have finally got his elusive World Series championship ring. But it was not to be. Cobb ended his career with 23 consecutive seasons batting .300 or better. The only season his batting average was under .300 was his rookie season, a Major League record that remained unbroken ever since.

Post-professional career

On account of his Coca-Cola deal, Cobb retired a very rich and successful man. He spent his retirement pursuing his off-season activities of hunting, golfing, and fishing, full-time. He also traveled extensively, both with and without his family. His other pastime was trading stocks and bonds, increasing his immense personal wealth.

In the winter of 1930, Cobb moved into a Spanish ranch estate on Spencer Lane in the millionaire's community of Atherton, California, outside San Francisco. At that same time, his wife Charlie filed the first of several divorce suits. Charlie finally divorced Cobb in 1947, after 39 years of marriage, the last few of which she lived in nearby Menlo Park.

In February 1936, when the first Hall of Fame election results were announced, Cobb had been named on 222 of 226 ballots, outdistancing Babe Ruth, Honus Wagner, Christy Mathewson, and Walter Johnson, the first year's induction class. His 98.2 percentage stood as the record until Tom Seaver received 98.8 percent of the vote in 1992 (Nolan Ryan and Cal Ripken have also surpassed Cobb, with 98.79 percent and 98.53 percent of the votes, respectively). People may have disliked him personally, but they respected the way he played and what he accomplished. In 1998, the Sporting News ranked him as third on the list of the 100 Greatest Baseball Players.

Later life

At the age of 62, Cobb married a second time in 1949. His new wife was 40-year-old Frances Fairbairn Cass, a divorcée from Buffalo, New York.[9] Their childless marriage also failed, ending with a divorce in 1956. At this time, Cobb became generous with his wealth, donating $100,000 in his parents' name for his hometown to build a modern 24-bed hospital, Cobb Memorial Hospital, which is now part of the Ty Cobb Healthcare System. He also established the Cobb Educational Fund, which awarded scholarships to needy Georgia students bound for college, by endowing it with a $100,000 donation in 1953 (equivalent to over $1 million today).

Cobb knew that another way he could share his wealth was by having biographies written that would both set the record straight on him and teach young players how to play. John McCallum spent some time with Cobb to write a combination how-to and biography titled The Tiger Wore Spikes: An Informal Biography of Ty Cobb that was published in 1956.[10]

It was also during his final years that Cobb began work on his autobiography, My Life in Baseball: The True Record, with writer Al Stump. Cobb retained editorial control over the book and the published version presented him in a positive light. Stump would later claim that the collaboration was contentious, and after Cobb's death Stump published two more books and a short story giving what he said was the "true story." One of these later books was used as the basis for the 1994 film Cobb (a box office flop starring Tommy Lee Jones as Cobb and directed by Ron Shelton). In 2010, an article by William R. "Ron" Cobb (no relation) in the peer-reviewed The National Pastime (the official publication of the Society for American Baseball Research) accused Stump of extensive forgeries of Cobb-related documents and diaries. The article further accused Stump of numerous false statements about Cobb in his last years, most of which were sensationalistic in nature and intended to cast Cobb in an unflattering light.[11]

Death and funeral

In his last days, Cobb spent some time with the movie comedian Joe E. Brown, talking about the choices Cobb had made in his life. He told Brown that he felt that he had made mistakes, and that he would do things differently if he could. He had played hard and lived hard all his life, and had no friends to show for it at the end, and he regretted it. Publicly, however, Cobb claimed not to have any regrets.

He checked into Emory Hospital for the last time in June 1961 after falling into a diabetic coma. His first wife, Charlie, his son Jimmy and other family members came to be with him for his final days. He died there on July 17, 1961, at age 74.

Cobb's funeral was perhaps the saddest event associated with Cobb. Cobb's family kept the event private, not trusting the media to give an accurate report. Approximately 150 friends and relatives attended a brief service in Cornelia, Georgia, and then drove to the Cobb family mausoleum in Royston for the burial.[12] Uniformed Little League players lined the road in the cemetery, and around 400 people had gathered to watch Cobb's casket carried into the mausoleum. Sadly, from all of baseball, the sport that he had dominated for over 20 years, baseball's only representatives at the ceremony were three old players, Ray Schalk, Mickey Cochrane, and Nap Rucker, along with Sid Keener from the Baseball Hall of Fame.[6]

Legacy

In his will, Cobb left a quarter of his estate to the Cobb Educational Fund, and the rest of his reputed $11 million he distributed among his children and grandchildren. Cobb is interred in the Royston, Georgia town cemetery. As of 2005, the Ty Cobb Educational Foundation has distributed nearly $11 million in scholarships to needy Georgians.[13]

Some historians, including Wesley Fricks, Dan Holmes, and Charles Leerhsen, have defended Cobb against unfair portrayals of him in popular culture since his death. A noted case is the book written by sportswriter Al Stump in the months after Cobb died in 1961. Baseball historians such as Doug Roberts and Ron Cobb point to Stump’s role in perpetuating the myths, exaggerations, and untruths that taint the memory of Ty Cobb.[14] Stump was discredited when it became known that he had stolen items belonging to Cobb and also betrayed the access Cobb gave him in his final months.[12]

Efforts to create a Ty Cobb memorial in Royston initially failed, primarily because most of the artifacts from his life were in Cooperstown, and the Georgia town was viewed as too remote to make a memorial worthwhile. However, on July 17, 1998, on the 37th anniversary of his death, the Ty Cobb Museum opened its doors in Royston. On August 30, 2005, his hometown hosted a 1905 baseball game to commemorate 100 years since Ty Cobb played his first game.

Regular season stats

| G | AB | R | H | 2B | 3B | HR | RBI | SB | CS | BB | SO | BA | OBP | SLG | TB | SH | HBP |

| 3,035 | 11,434 | 2,246 | 4,191 | 724 | 295 | 117 | 1,937 | 892 | 178 | 1,249 | 357 | .366 | .433 | .512 | 5,854 | 295 | 94 |

Notes

- ↑ James Peach, “Thorstein Veblen, Ty Cobb, and the Evolution of an Institution,” Journal of Economic Issues 38, no. 2 (June 2004): 328.

- ↑ Craig Muder, First BBWAA Election in 1936 Produced Historic National Baseball Hall of Fame. Retrieved April 30, 2023..

- ↑ All Time Totals - Hitting Major League Baseball. Retrieved April 30, 2023.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Ty Cobb (1886–1961) New Georgia Encyclopedia. Retrieved April 27, 2023.

- ↑ Ty Cobb and Al Stump, My Life in Baseball: The True Record (Bison Books, 1993 (original 1961), ISBN 978-0803263598).

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 Charles C. Alexander, Ty Cobb (Oxford University Press, 1984, ISBN 0195035984).

- ↑ Joseph Durso, The Days of Mr. McGraw (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1969, ISBN 0131972510), 69.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Stewart Wolpin, Ty Cobb BaseballBiography.com. Retrieved April 30, 2023.

- ↑ Al Stump, Cobb (Algonquin Books, 1994, ISBN 1565121449).

- ↑ John McCallum, The Tiger Wore Spikes: An Informal Biography of Ty Cobb (Hassell Street Press, 2021 (original 1956), ISBN 978-1013586040).

- ↑ William R. Cobb, The Georgia Peach Stumped by the Storyteller 2010. Retrieved April 30, 2023.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Frank Russo, The Cooperstown Chronicles: Baseball's Colorful Characters, Unusual Lives, and Strange Demises (Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2014, ISBN 978-1442236394).

- ↑ Ty Cobb Educational Foundation Retrieved April 30, 2023.

- ↑ Gilbert King, The Knife in Ty Cobb’s Back Smithsonian Magazine, August 30, 2011. Retrieved April 30, 2023.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Alexander, Charles C. Ty Cobb. Oxford University Press, 1984. ISBN 0195035984

- Bak, Richard. Ty Cobb: His Tumultuous Life and Times. Taylor, 1994. ISBN 0878338705

- Cobb, Ty, and Al Stump. My Life in Baseball: The True Record. Bison Books, 1993 (original 1961). ISBN 978-0803263598

- Durso, Joseph. The Days of Mr. McGraw. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1969. ISBN 0131972510

- McCallum, John. The Tiger Wore Spikes: An Informal Biography of Ty Cobb. Hassell Street Press, 2021 (original 1956). ISBN 978-1013586040

- Pietrusza, David, Matthew Silverman, and Michael Gershman (eds.). Baseball: The Biographical Encyclopedia. Total/Sports Illustrated, 2000. ISBN 1892129345

- Russo, Frank. The Cooperstown Chronicles: Baseball's Colorful Characters, Unusual Lives, and Strange Demises. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2014. ISBN 978-1442236394

- Stump, Al. Cobb: A Biography. Algonquin, 1994. ISBN 1565121449

External links

All links retrieved May 2, 2023.

- Ty Cobb National Baseball Hall of Fame

- The Ty Cobb Museum

- Ty Cobb Educational Foundation

- Ty Cobb Baseball Atheneum Repository

- The Knife in Ty Cobb’s Back by Gilbert King, Smithsonian Magazine, August 30, 2011.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.