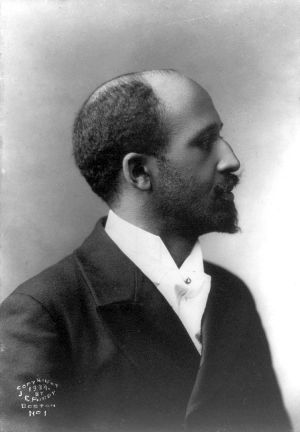

W. E. B. Du Bois

William Edward Burghardt Du Bois pronounced [du'bojz] (February 23, 1868 â August 27, 1963) was an American civil rights activist, sociologist, and educator, widely recognized as the foremost black intellectual and principal black protest spokesperson in the United States during the first half of the twentieth century. As a rigorous academician, he excelled in college; enjoyed tenure at numerous teaching posts; produced more than 4,000 published works over the course of his life; and became an heroic exemplar to those who would eventually coalesce as the American black intelligentsia. In his role as a scholar activist, he went beyond the confines of the classroom and the halls of academia, in his quest to solve what he called "The problem of the twentieth centuryâthe problem of the color line."

Du Bois is viewed by many as the father of modern black scholarship, modern black militancy and self-consciousness, and modern black cultural development. The sole black co-founder of the NAACP, his legacy of social change through efforts to end legalized racial segregation remains outstanding. However, Du Bois was frustrated by the lack of recognition of his social theories, notably "The Talented Tenth," and became disillusioned with American society. In 1963, at the age of 95, he became a naturalized citizen of Ghana, renouncing his American citizenship, and choosing to live his final days as a self-exiled Communist, his dream of seeing the end of racism in America unfulfilled.

Biography

William Edward Burghardt Du Bois (known as W.E.B. Du Bois) was born at Church Street, on February 23, 1868, in Great Barrington, Massachusetts, in the United States, the son of Alfred Du Bois and Mary Silvina Burghardt Du Bois. The couple's February 5, 1867 wedding had been announced in the Berkshire Courier. Alfred Du Bois was born in San Domingo, now known as Haiti. Alfred Du Bois, himself, was descended from free people of color, and he could trace his lineage back to one Dr. James Du Bois of Poughkeepsie, New York. This physician, while in the Bahamas, had sired, by his slave mistress, three sonsâincluding Alfredâand a daughter.

His son was born one year after the ratification and addition of the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution. Intellectually gifted and scholastically oriented, W.E.B. Du Bois, in 1883, graduated earlyâat age fifteenâfrom Great Barrington High School. He was the only black student in his graduating class.

In 1890, two years after receiving his Bachelor's degree from Fisk University, Du Bois graduated cum laude, with a Master's degree from Harvard University. He then went abroad, to study at the University of Berlin. In 1894, at the age of 26, he returned to America and taught at Wilberforce University. The next year, Du Bois became the first black person to receive a Ph.D. from Harvard University. This advanced degree was in history, despite the fact that Du Bois' primary training was in the social sciences. His doctoral dissertation, The Suppression of the African Slave Trade to the United States of America, 1638-1870 (1896), was a foretaste of the type of observational investigations and case studies he would produce in the years to come.

W.E.B. Du Bois married Nina Gomer in 1896. From this union were born two children: a son (Burghardt), who died a toddler, and a daughter (Yolande). A year after Nina's death in 1950, he wedded his second wife, Shirley Graham, who survived him.

Following his professorship at Wilberforce, he taught at the University of Pennsylvania, where he published the trailblazing sociological study, The Philadelphia Negro (1899). He then went on to Atlanta University (present-day Clark Atlanta University), where he established one of the first departments of sociology in the United States, and where he systematized a sequence of studies exploring the life and history of American blacks (Rashidi 1998).

The post-Reconstruction-Era U.S. was rife with such ills as Jim Crow segregation laws, lynchings, race riots, and disfranchisement, all of which evinced a context of racism. Prior to his graduation from Fisk University, one of the premiere black institutions of higher learning, the young Du Bois had already resolved to take up the mission of liberating black America from oppression. He envisioned himself as a destined race leader.

A diligent seeker of truth, Du Bois spent the period from 1910-1934 on leave from his Atlanta University teaching post, as he explored one potential method after another for solving the intractable race crisis. Steeped in academia, research, and publication, Du Bois was initially passionate in his conviction that, through social science, the knowledge to resolve the race problem would be found. In addition, he firmly believed that a college degree was essential, since it furnished young blacks with the insight and intellectual competency required to be of service to the race. Thus, his background was quite different from that of Booker T. Washington, the most influential black leader of that time, and Du Bois developed a very different perspective regarding what had to be done to bring about racial reconciliation and harmony. Ultimately, however, the steadily worsening racial climate of his day drove him gradually to the conclusion that only through agitation and protest could genuine social transformation be wrought. Additionally, the ideological controversy between Du Bois and Washington grew into a bitter, personal battle between the two men.

The Atlantan professor's attraction to Socialism and Marxism increased throughout the 1920s. During a 1926 visit to the Soviet Union, he stated, "If what I've seen with my eyes and heard with my ears in Russia is Bolshevism, then I am a Bolshevik." This statement was evidence of a profound change of heart and direction. That shift had come about as a result of Du Bois' connections to early socialists like Charles E. Russell, Mary White Ovington, William E. Walling, and Joel E. Spingarn, who, together with Du Bois, were the ground-floor architects of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).

By 1934, Du Bois had resigned as editor of the NAACP publication, Crisis, and had resumed his professorship at Atlanta University. His years of having conflicted with NAACP Executive Secretary, Walter White, had left Du Bois frustrated. In addition, he was greatly disillusioned over the fact that his idea of a nationalist Pan-African Movement had fallen on deaf ears. Also, his theory of "The Talented Tenth," as black America's most exemplary elite, who would embody the intelligence and the competency needed to pull the entire race up to full citizenship, had found few takers.

By the mid-1930s, Du Bois' ties with the ideological Left had brought him some serious problems. His crusades for "voluntary segregation" and "economic separatism" triggered aspersions from other intellectuals. As he increasingly identified himself with pro-Marxist causes, he attracted the watchful eye of the federal government. Indicted and acquitted in 1951 of charges that he was a subversive agent of a foreign government, he became disillusioned with America. In a 1961 letter to Gus Hall, then leader of the Communist Party of the USA, Du Bois wrote,

"Today I have reached a firm conclusion that Capitalism cannot reform itself. It is doomed to self destruction. No universal selfishness can bring social good to all. Communism⌠is the only way of human life."

Two years later, in Ghana, as an official Communist Party member, Du Bois died.

Career

Academic work

Among Du Bois' works that contribute to the fields of education and sociology, highly ranked is his Ph.D. dissertation, The Suppression of the African Slave Trade, which was extolled as the "first scientific historical work" authored by a black person. It was published as the initial volume of the then new series of Harvard Historical Studies (1896). In addition, Du Bois' (1899) The Philadelphia Negro: A Social Study is a trailblazing effort with regard to the sociological analysis of the black American.

His The Souls of Black Folk (1903) is a book of essays that concretized his opposition to Booker T. Washington's approach to overcoming racism. Washington advocated providing young black men and women with relevant, practical, and employable skills, through which they would effectively play an economic role in society. He believed that blacks would naturally become respected and would realize full-fledged financial and cultural parity with American whites on that basis. Du Bois was adamant that such an approach would fail, condemning the black population to forever being regarded as inferior.

In The Negro Problem: A Series of Articles by Representative Negroes of To-day (1903) Du Bois presented his opposing view, namely that higher education was necessary to develop leadership among the most able ten percent of black Americans. In order to achieve political and civil equality, Du Bois believed that this "talented tenth" of the black population should be educated as professionals, academics, teachers, ministers, and spokesmen, who would then be able to lead the black population and lift them up to their true position in society:

Men of America, the problem is plain before you. Here is a race transplanted through the criminal foolishness of your fathers. Whether you like it or not the millions are here, and here they will remain. If you do not lift them up, they will pull you down. Education and work are the levers to uplift a people. Work alone will not do it unless inspired by the right ideals and guided by intelligence. Education must not simply teach workâit must teach Life. The Talented Tenth of the Negro race must be made leaders of thought and missionaries of culture among their people. No others can do this and Negro colleges must train men for it. The Negro race, like all other races, is going to be saved by its exceptional men. (Du Bois 1903)

Du Bois promoted the idea that differences between the races may indeed exist, offering the concept of "racialism," which, he contended, must be distinguished from "racism." He suggested that racialism refers to the idea that human racial differences exist, whether they be biological, psychological, or transcendental. Racism, then, is the use of this idea to advance the notion that one's own particular race is inherently superior to all others. Thus, Du Bois separated the conditions from the action of racism.

Civil Rights activism

In 1895, from his teaching post at Wilberforce University, the young Du Bois joined the throng of Americans around the country who congratulated Booker T. Washington on his landmark Atlanta Exposition Address. At that point, Du Bois was in agreement with Washington that fervent faith in God, strong families, and economic stability were indispensable for black uplift.

Eight years later, however, Du Bois openly attacked Washington, denouncing him and his program as hindrances to authentic black advancement, and insisting that the Washingtonian approach would not serve the long-term interests of blacks as a whole:

The black men of America have a duty to perform, a duty stern and delicateâa forward movement to oppose a part of the work of their greatest leader. âŚso far as Mr. Washington apologizes for injustice, North or South, does not rightly value the privilege and duty of voting, belittles the emasculating effects of caste distinctions, and opposes the higher training and ambition of our brighter mindsâso far as he, the South, or the Nation, does thisâwe must unceasingly and firmly oppose themâŚ. (Of Mr. Booker T. Washington and Others 1903)

As the zealous, idealistic members of a black intelligentsia began to organize themselves around Du Bois, their goal was clearâthe immediate attainment of full civil rights for blacks, and the immediate elimination of racism in the USA. In 1905, this group founded the Niagara Movement (so called because their first meeting was held at the Niagara Falls in Canada when no hotel would house them on the American side). Their leaders were Du Bois and another Harvard-educated, Northeastern black, named William Monroe Trotter. Trotter, however, insisted that no white people be included in the organization, while Du Bois maintained that an interracial alliance was imperative.

Following the split between these two leaders, Du Bois, in 1909, became the chief black founder of the interracial National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). In 1910, he left his teaching post at Atlanta University to work full-time as the organization's publications director. By regularly publishing such Harlem Renaissance writers as Langston Hughes and Jean Toomer, Du Bois held black America's attention. Using strategic editorialism, he so persuasively impacted his readership that the magazine's circulation soared from 1,000 in 1910 to more than 100,000 by 1920, at the same time setting the agenda of the fledgling NAACP (Bock 1997).

Du Bois' civil-rights vision was braced atop three pillars: (1) setting blacks free by the dispassionate presentation of philosophical and sociological Truth (his capitalization); (2) racial advancement via manly agitation and clamorous protest against oppression; and (3) uplifting the race via the training and leadership of "The Talented Tenth." However, these ideas did not gain serious traction in black America until some ten years before Du Boisâ death.

The seminal debate between Booker T. Washington and Du Bois played out in the pages of the Crisis, with Washington advocating an accommodational philosophy of self-help and vocational training while Du Bois pressed for full educational opportunities for blacks. Du Bois also used the Crisis to attack Marcus Garvey and his nationalist Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA). Additionally, Du Bois wrote weekly columns in many newspapers, including the Hearst-owned San Francisco Chronicle, and three black-owned publicationsâthe Chicago Defender, the Pittsburgh Courier, and the New York Amsterdam News. During this period the disagreement between Du Bois and Booker T. Washington over their approaches to solving the racial divide in America had become a personal and acrimonious rivalry.

After Washington's death in 1915, Du Bois was heartened by the prospect that he would no longer be hindered by a leadership struggle with the Tuskegeean. By the following year, Du Bois had replaced Washington as America's most prominent black leader. From 1916-1930, increasing numbers of blacks were embracing the Atlantan professor's doctrine of advancement through protest and agitation. Yet, as he and the NAACP shifted from black America's "radical" fringe to the centrist position, Du Bois often found himself necessarily encouraging the same tactics for which he had opposed Washington. And, in response, ironically, heaped upon Du Bois were the same criticisms he had wreaked upon his old rival.

Waxing more and more radically Leftist, Du Bois found himself increasingly at odds with leaders such as Walter Francis White and Roy Wilkins. Finally, in 1934, after penning in the Crisis two essays suggesting that black separatism could be a useful economic strategy, Du Bois quit the magazine and returned to his Atlanta University professorship.

In the aftermath of the Japanese victory in the Russo-Japanese War, Du Bois became impressed by the growing strength of Imperial Japan. He interpreted the victory of Japan over Tsarist Russia as an example of "colored pride," and became a willing part of Japan's "Negro Propaganda Operations." In 1936, Du Bois and a small group of his fellow academics participated in a tour that included stops in Japan, China, and the Soviet Union, although the Soviet leg was canceled because Du Boisâ diplomatic contact, Karl Radek, had been swept up in Stalin's purges. While on the Chinese leg of the trip, Du Bois commented that the source of Chinese-Japanese enmity was China's "submission to white aggression and Japan's resistance," and he asked the Chinese people to welcome the Japanese as liberators.

Du Bois was investigated by the FBI, who claimed, in May of 1942, that "[h]is writing indicates him to be a socialist," and that he "has been called a Communist and at the same time criticized by the Communist Party." He was indicted in the United States under the Foreign Agents Registration Act, but was acquitted for lack of evidence.

Du Bois visited Communist China during the Great Leap Forward. In the March 16, 1953 issue of The National Guardian, Du Bois wrote "Joseph Stalin was a great man; few other men of the twentieth century approach his stature." He was chairman of the Peace Information Center at the start of the Korean War. He was among the signers of the Stockholm Peace Pledge, which opposed the use of nuclear weapons. In 1959, Du Bois received the Lenin Peace Prize.

Finally, Du Bois' disillusionment with both black capitalism and racism in the United States was complete. In 1961, at the age of 93, he joined the Communist Party, announcing his membership in The New York Times.

Du Bois was invited to Ghana in 1961, by President Kwame Nkrumah, to direct the Encyclopedia Africana, a government production, and a long-held Du Bois dream. When, in 1963, he was refused a new U.S. passport, he and his wife, Shirley Graham Du Bois, renounced their American citizenship, and became citizens of Ghana. Du Boisâ health had declined in 1962, and on August 27, 1963, he died in Accra, Ghana at the age of 95, one day before Martin Luther King, Jr.'s I Have a Dream speech.

Legacy

W.E.B. Du Bois holds a unique place in the history of twentieth century America. His achievements as a scholar, prolific writer, editor, poet, and historian earned him the honor, in 1943, of being the first black admitted to the National Institute of Arts and Letters. The W.E.B. Du Bois Institute for African and African American Research was established in his honor at Harvard University, to provide fellowships intended to "facilitate the writing of doctoral dissertations in areas related to Afro-American studies." In 1992, the United States honored Du Bois with a postage stamp bearing his likeness. On October 5, 1994, the main library building at the University of Massachusetts Amherst was named for him. Numerous other educational and public buildings also bear his name, which serves as an inspiration to black youth that their race is no barrier to their educational aspirations and life goals.

Du Boisâ acclaimed biographer, David Levering Lewis, wrote: "In the course of his long, distinguished career, W.E.B. Du Bois attempted virtually every possible solution for the problem of twentieth-century racismâscholarship, propaganda, integration, cultural and economic separatism, politics, international communism, expatriation, and third-world solidarity." (W.E.B. Du BoisâThe Fight For Equality And The American Century: 1919-1963)

In 1899, the American Historical Association (AHA) convened in Boston and Cambridge. According to Du Bois biographer, David Levering Lewis: "The Association then numbered fifteen hundred members and was presided over by James Ford Rhodes, successful Ohio businessman and even more successful author of the arbitral, multi-volume History of the United States from the Compromise of 1850. At this 1899 meeting, there were no Jews, no Negroes, no women to speak of, and all the gays were in the closet" (Lewis 1994). In 1909, W.E.B. Du Bois addressed the AHA. Lewis noted that "His would be the first and last appearance of an African-American on the program until 1940."

In a review of Part II of Lewis's biography of Du Bois, Winston (2000) observed that one historical question, not often addressed, is still fundamental to an understanding of American history. That question is, "How black Americans developed the psychological stamina and collective social capacity to cope with the sophisticated system of racial domination that white Americans had anchored deeply in law and custom." Winston continued, "Although any reasonable answer is extraordinarily complex, no adequate one can ignore the man (Du Bois) whose genius was for 70 years at the intellectual epicenter of the struggle to destroy white supremacy as public policy and social fact in the United States."

Du Bois has been credited with sublime brilliance regarding his articulation of American black protest against racial oppression. As the sole, black co-founder of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), Du Bois played an essential role in America's historical struggle to make tangible the promises of democracy. He is also seen as having been an influential figure with regard to the Pan-African Movement, since the convening of the first Pan-African Congress in 1919. Black America has W.E.B. Du Bois to thank for the massive popularization of "The Talented Tenth" theory. The idea that a college-educated, articulate, cultured, and meritorious elite would arise from the ranks of the black masses and point the way to a better racial future, compelled many young blacks to aspire for academic excellence, in order to be qualified when the opportunity for leadership presented itself.

On a different note, however, Du Bois bears the main responsibility for an acrimonious leadership split that created two black Americas and weakened the group's solidarity. Because his own sociological theories and proposals were virtually ignored by influential, majority-group reformers such as Booker T. Washington and Marcus Garvey, Du Bois took umbrage. Embracing Marxist ideas, and ultimately abandoning American Capitalism and democracy in favor of Communism, Du Bois pursued an aggressive path of personal and social agitation, protest, and verbal conflict. Nevertheless, it was because of Du Boisâ twenty-five years of effort and impact that the NAACP eventually became, and still remains, America's premiere and most influential civil rights organization.

Publications

- Du Bois, W.E.B. 1896. The Suppression of the African Slave Trade to the United States of America: 1638â1870 Ph.D. dissertation. Harvard Historical Studies, New York: Longmans, Green, and Co. Retrieved June 10, 2008.

- Du Bois, W.E.B. [1897] 1910. Atlanta University's Studies of the Negro Problem.

- Du Bois, W.E.B. 1897. "The Conservation Of Races" in The American Negro Academy Occasional Papers. Retrieved June 10, 2008.

- Du Bois, W.E.B. 1898. The Study of the Negro Problems.

- Du Bois, W.E.B. [1899] 1995. The Philadelphia Negro. University of Pennsylvania Press; Reprint edition. ISBN 0812215737

- Du Bois, W.E.B. 1899. The Negro in Business.

- Du Bois, W.E.B. 1901. "The Evolution of Negro Leadership" in The Dial 31 (July 16, 1901).

- Du Bois, W.E.B. [1903] 1999. The Souls of Black Folk. New York: W. W. Norton & Company; New Ed edition. ISBN 039397393X

- Du Bois, W.E.B. 1903. "The Talented Tenth." Chapter 2 of The Negro Problem. A collection of articles by African Americans. September 1903.

- Du Bois, W.E.B. 1905. Voice of the Negro II.

- Du Bois, W.E.B. [1909] 1997. John Brown: A Biography. M.E. Sharpe. ISBN 1563249723

- Du Bois, W.E.B. [1909] 1985. Efforts for Social Betterment among Negro Americans. Periodicals Service Co; Rep edition. ISBN 0527031151

- Du Bois, W.E.B. [1911] 2004. The Quest of the Silver Fleece. Pine Street Books; Reprint edition. ISBN 0812218922

- Du Bois, W.E.B. [1915] 2001. The Negro. University of Pennsylvania Press, ISBN 0812217756

- Du Bois, W.E.B. [1920] 2005. Darkwater: Voices from Within the Veil. IndyPublish.com. ISBN 1421947749

- Du Bois, W.E.B. [1924] 1971. The Gift of Black Folk. AMS Pr. Inc. ISBN 0404001521

- Du Bois, W.E.B. [1928] 1995. Dark Princess: A Romance. University Press of Mississippi; Reissue edition. ISBN 087805765X

- Du Bois, W.E.B. [1930] 1977. Africa, its Geography, People and Products. Millwood, NY: Kraus Intl Pubns. ISBN 0527252603

- Du Bois, W.E.B. [1930] 2007. Africa: Its Place in Modern History. reprint ed, Oxford University Press, 2007. ISBN 019532580X

- Du Bois, W.E.B. [1935] 2006. Black Reconstruction: An Essay toward a History of the Part which Black Folk Played in the Attempt to Reconstruct Democracy in America, 1860-1880. University of Notre Dame Press. ISBN 0268021643

- Du Bois, W.E.B. 1936. What the Negro has Done for the United States and Texas. U.S. Gov't. Printing Office. ASIN: B000868TX6

- Du Bois, W.E.B. 1939. Black Folk, Then and Now. London: Octagon Books. ISBN 0374923590

- Du Bois, W.E.B. [1940] 1983. Dusk of Dawn: An Essay Toward an Autobiography of a Race Concept. Transaction Publishers; Reprint edition. ISBN 0878559175

- Du Bois, W.E.B. [1945] 1975. Color and Democracy: Colonies and Peace. Millwood, NY: Kraus Int'l. Pub. ISBN 0527252905

- Du Bois, W.E.B. 1946. The Encyclopedia of the Negro. a 200 page presented to the Phelps-Stokes Fund in 1946. project was never completed.

- Du Bois, W.E.B. [1946] 1979. The World and Africa. International Publishers; Rev edition. ISBN 0717802213

- Du Bois, W.E.B. [1947] 1983. The World and Africa, An Inquiry into the Part Which Africa has Played in World History. International Publishers. ASIN B000JWLPDK

- Du Bois, W.E.B. 1951. Peace is Dangerous.

- Du Bois, W.E.B. 1951. I take my stand for Peace.

- Du Bois, W.E.B. 1952. In Battle for Peace. Kraus Intl Pubns. ISBN 0527252654

- Du Bois, W.E.B. [1957] 1976. The Ordeal of Mansart. Kraus Intl Pubns. ISBN 0527252700

- Du Bois, W.E.B. [1959] 1976. Mansart Builds a School. Kraus Intl Pubns. ISBN 0527252719

- Du Bois, W.E.B. 1960. Africa in Battle Against Colonialism, Racialism, Imperialism.

- Du Bois, W.E.B. 1961. Worlds of Color.

- Du Bois, W.E.B. [1963] 1969. An ABC of Color: Selections from Over a Half Century of the Writings of W.E.B. Du Bois. International Publishers. ISBN 0717800008

- Du Bois, W.E.B. 1968. The Autobiography of W.E. Burghardt Du Bois. International Publishers. ISBN 0717802345

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Bock, James. 1997. "A New and Changed NAACP Magazine" in The Baltimore Sun. June 8, 1997.

- Broderick, Francis L. 1959. W.E.B. Du Bois: Negro Leader in a Time of Crisis. Stanford University Press.

- Du Bois, W.E.B. 1968. The Autobiography of W. E. Burghardt Du Bois: A Soliloquy on Viewing My Life from the Last Decade of Its First Century. New York: International Publishers Co. Inc.

- Horne, Gerald. 1986. Black and Red: W. E. B. Du Bois and the Afro-American Response to the Cold War, 1944-1963. State University of New York Press. ISBN 0887060889

- Lewis, David Levering. 2001. W.E.B. Du Bois: The Fight for Equality and the American Century 1919-1963.. Owl Books. Winner of the 2001 Pulitzer Prize for Biography The Pulitzer Prize Winners - Biography. Retrieved June 10, 2008.

- Marable, Manning. [1987] 2005. W.E.B Du Bois: Black Radical Democrat, updated ed. Paradigm Publishers. ISBN 1594510199

- Meier, August. 1964. Negro Thought in America, 1880-1915: Racial Ideologies in the Age of Booker T. Washington. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0472061186

- Rampersad, Arnold. [1976] 1990. The Art and Imagination of W. E. B. Du Bois. reprint Schocken Press. ISBN 0805209859

- Rashidi, Runoko. 1998. W.E.B. Du Bois. Retrieved June 10, 2008.

- Rudwick, Elliott M. [1960] 1972. W. E. B. Du Bois: Propagandist of the Negro Protest. Atheneum reprint.

- Sundquist, Eric J. (ed.). 1996. The Oxford W.E.B. Du Bois Reader. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195091787

- Winston, Michael R. 2000. Washington Post. November 5, 2000.

External Links

All links retrieved May 3, 2023.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.