William F. Buckley, Jr.

| William F. Buckley Jr. | |

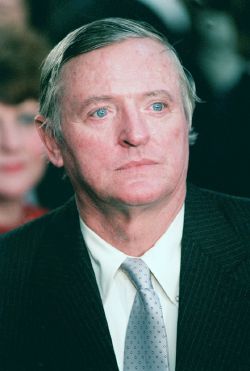

William F. Buckley Jr. in 1985

| |

| Born | November 24 1925 New York City, United States |

|---|---|

| Died | February 28, 2008 (aged 82) Stamford, Connecticut, United States |

| Nationality | American |

| Occupation | Author Commentator Television personality |

| Religious beliefs | Roman Catholic |

| Spouse(s) | Patricia Taylor Buckley (d. 2007) |

| Children | Christopher Buckley (b.1952) |

William Frank Buckley Jr. (November 24, 1925 – February 28, 2008) was an American author and conservative commentator. He founded the political magazine National Review in 1955, hosted 1429 episodes of the television show Firing Line from 1966 until 1999, and was a nationally syndicated newspaper columnist.

Buckley was the spiritual "godfather" of the modern American conservative movement. He helped pave the way for the unsuccessful Presidential bid of Barry Goldwater, and the later Presidency of Ronald Reagan.

In the wake of the New Deal and the growth of influence of Keynesian economics on modern liberal government, Buckley was among the first public intellectuals to make that case for smaller government and laissez-faire economics. He was also known as a fierce opponent of communism, including arguing the case for McCarthyism.

Buckley came on the public scene with his critical book God and Man at Yale (1951); among over fifty further books on writing, speaking, history, politics and sailing, were a series of novels featuring CIA agent Blackford Oakes.

Early life

Buckley was born in New York City to lawyer and oil baron William Frank Buckley, Sr., of English and Irish descent, and Aloise Josephine Antonia Steiner, a native of New Orleans and of Swiss-German descent. The sixth of ten children, as a boy Buckley moved with his family from Mexico to Sharon, Connecticut before beginning his first formal schooling in Paris, where he attended first grade. By age seven, he received his first formal training in English at a day school in London; his first and second languages were Spanish and French, respectively.[1] As a boy, Buckley developed a love for music, sailing, horses, hunting, skiing, and story-telling. All of these interests would be reflected in his later writings. Just before World War II, at age 13, he attended high school at the Catholic Beaumont College in England. During the war, his family took in the future British historian Alistair Horne as a child war evacuee. Buckley and Horne remained life-long friends. Buckley and Horne both attended the Millbrook School, in Millbrook, New York, and graduated as members of the Class of 1943. At Millbrook, Buckley founded and edited the school's yearbook, The Tamarack, his first experience in publishing. When Buckley was a young man, his father was an acquaintance of libertarian author Albert Jay Nock. William F. Buckley, Sr., encouraged his son to read Nock's works.

In his younger years, Buckley developed many musical talents; he played the harpsichord very well—later calling it "the instrument I love beyond all others."[2] He was an accomplished pianist and appeared once on Marian McPartland's National Public Radio show "Piano Jazz."[3] A great fan of Johann Sebastian Bach,[2] Buckley said that he wanted Bach's music played at his funeral.[4]

Marriage and family

In 1950, Buckley married Patricia Aldyen Austin "Pat" Taylor (1926 –2007), daughter of industrialist Austin C. Taylor. He met Pat, a Protestant from Vancouver, British Columbia, while she was a student at Vassar College in Poughkeepsie, New York. She later became a prominent charity fundraiser for such organizations as the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, the Institute of Reconstructive Plastic Surgery at New York University Medical Center and the Hospital for Special Surgery. She also raised money for Vietnam War veterans and AIDS patients. On April 15, 2007, at age 80 she died of an infection after a long illness. After her death, Buckley's friend, Christopher Little, said Buckley "seemed dejected and rudderless." The couple had one son, author Christopher Buckley. Buckley took great pride in the success of his son, and in his final years would frequently call friends late at night to read them passages from "Christo's" latest book.

Buckley had nine siblings, including sister Maureen Buckley-O'Reilly, who married Gerald O'Reilly and had several children before suddenly dying of a brain aneurysm in 1966; sister Priscilla L. Buckley, author of Living It Up With National Review: A Memoir for which William wrote the foreword; sister Patricia Lee Buckley Bozell, who was Patricia Taylor's roommate at Vassar before each married; brother Fergus Reid Buckley, an author, debate-master, and founder of the Buckley School of Public Speaking; and brother James L. Buckley, a former senior judge of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit, and a former U.S. Senator from New York. William and James appeared together on Firing Line. Buckley co-authored a book, McCarthy and His Enemies, with Patricia's husband L. Brent Bozell Jr.

He resided in New York City and Stamford, Connecticut. He was a practicing Catholic, regularly attending the traditional Latin Mass in Connecticut.

Education, military service and the CIA

| The Conservatism series, part of the Politics series |

| Schools |

| Cultural conservatism |

| Liberal conservatism |

| Social conservatism |

| National conservatism |

| Neoconservatism |

| Paleoconservatism |

| Libertarian conservatism |

| Ideas |

| Fiscal frugality |

| Private property |

| Rule of law |

| Social order |

| Traditional society |

| Organizations |

| Conservative parties |

| Int'l Democrat Union |

| European Democrats |

| National Variants |

| Australia |

| Canada |

| Colombia |

| Germany |

| United States

|

| Politics Portal |

Buckley attended the National Autonomous University of Mexico (or UNAM) in 1943. The following year upon his graduation from the U.S. Army Officer Candidate School, he was commissioned as a second lieutenant in the U.S. Army. In his book, Miles Gone By, he briefly recounts being a member of Franklin D. Roosevelt's honor guard when the president died.

With the end of World War II in 1945, he enrolled in Yale University, where he became a member of the secret Skull and Bones society,[5]was a debater, an active member of the Conservative Party and of the Yale Political Union, and served as Editor-in-Chief of the Yale Daily News.

Buckley studied political science, history and economics at Yale, graduating with honors in 1950. He excelled as the captain of the Yale Debate Team, and under the tutelage of Yale professor Rollin G. Osterweis, Buckley honed his acerbic style. Osterweis recalled that Buckley showed up at the annual Harvard-Yale debate in a jacket and tie and shorts. When quizzed about his outfit, Buckley responded that he "thought it would be a sporting contest."

In 1951, like some of his classmates in the Ivy League, Buckley was recruited into the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), yet he served for less than a year. Little has been published regarding Buckley's work with the CIA, but in a 2001 letter to author W. Thomas Smith, Jr., Buckley wrote, "I did training in Washington as a secret agent and was sent to Mexico City. There I served under the direct supervision of [former Watergate conspirator] Howard Hunt, about whom, of course, a great deal is known."

In a November 1, 2005, editorial for National Review, Buckley recounted that:

An autobiographical illustration. When in 1951 I was inducted into the CIA as a deep-cover agent, the procedures for disguising my affiliation and my work were unsmilingly comprehensive. It was three months before I was formally permitted to inform my wife what the real reason was for going to Mexico City to live. If, a year later, I had been apprehended, dosed with sodium pentothal, and forced to give out the names of everyone I knew in the CIA, I could have come up with exactly one name, that of my immediate boss (E. Howard Hunt, as it happened). In the passage of time one can indulge in idle talk on spook life. In 1980 I found myself seated next to the former president of Mexico at a ski-area restaurant. What, he asked amiably, had I done when I lived in Mexico? "I tried to undermine your regime, Mr. President." He thought this amusing, and that is all that it was, under the aspect of the heavens.[6]

While in Mexico, Buckley edited The Road to Yenan, a book by Peruvian author Eudocio Ravines addressing the communist quest for global domination.

Career

First books

In 1951, the same year he was recruited into the CIA, Buckley's first book God and Man at Yale was published. A critique of Yale University, the work argues that the school had strayed from its original educational mission. The next year, he made some telling concessions in an article for Commonweal.

We have got to accept Big Government for the duration—for neither an offensive nor a defensive war can be waged…except through the instrument of a totalitarian bureaucracy within our shores.[7]

In 1954, Buckley co-wrote a book McCarthy and His Enemies with his brother-in-law, L. Brent Bozell, Jr., strongly defending Senator Joseph McCarthy as a patriotic crusader against communism.

National Review, Young Americans for Freedom, Barry Goldwater

Buckley worked as an editor for The American Mercury in 1951 and 1952, but left after spotting anti-Semitic tendencies in the magazine. He then founded National Review in 1955, serving as editor-in-chief until 1990. During that time, National Review became the standard-bearer of American conservatism, promoting the fusion of traditional conservatives and libertarians. Buckley was a defender of McCarthyism. In McCarthy and his Enemies he asserted that "McCarthyism … is a movement around which men of good will and stern morality can close ranks."[8]

In 1957, Buckley published Whittaker Chambers' review of Ayn Rand's Atlas Shrugged ostensibly "reading her out of the conservative movement."[9] Objectivists have accused Chambers of merely skimming the novel.[10] Buckley said that Rand never forgave him for publishing the review and that "for the rest of her life, she would walk theatrically out of any room I entered!"[1]

Also in 1957, Buckley came out in support of the segregationist South, famously[11] writing that "the central question that emerges … is whether the White community in the South is entitled to take such measures as are necessary to prevail, politically and culturally, in areas where it does not predominate numerically? The sobering answer is Yes – the White community is so entitled because, for the time being, it is the advanced race."[12] Buckley changed his views and by the mid-1960s renounced racism. This change was caused in part because of his reaction to the tactics used by white supremacists against the civil rights movement, and in part because of the influence of friends like Garry Wills, who confronted Buckley on the morality of his politics.[13]

By the late 1960s, Buckley disagreed strenuously with segregationist George Wallace, and Buckley later said it was a mistake for National Review to have opposed the civil rights legislation of 1964-1965. He later grew to admire Martin Luther King, Jr. and supported creation of a national holiday for him. As late as 2004, he defended his statement, at least the part referring to African Americans not being "advanced." He pointed out the word "Advancement" in the name NAACP and continued, "The call for the 'advancement' of colored people presupposes they are behind. Which they were, in 1958, by any standards of measurement."[11] During the 1950s, Buckley had worked to remove anti-Semitism from the conservative movement and barred holders of those views from working for National Review.

In 1960, Buckley helped form Young Americans for Freedom and in 1964 he strongly supported the candidacy of Arizona Senator Barry Goldwater, first for the Republican nomination against New York Governor Nelson Rockefeller and then for the Presidency. Buckley used National Review as a forum for mobilizing support for Goldwater.

In 1962, Buckley denounced Robert W. Welch, Jr., and the John Birch Society, in National Review, as "far removed from common sense" and urged the GOP to purge itself of Mr. Welch's influence.[14]

On The Right

Buckley's column On The Right was syndicated by Universal Press Syndicate beginning in 1962. From the early 1970s, his twice-weekly column was distributed to more than 320 newspapers across the country. In the early 1960s, at Sharon, Connecticut, Buckley founded the conservative political youth group, "Young Americans for Freedom" (YAF). Young Americans for Freedom was guided by principles Buckley called, "The Sharon Statement." The successful campaign of his elder brother Jim Buckley's to capture the U.S. Senate seat from New York State held by incumbent Republican Charles Goodell on the Conservative Party ticket in 1970 was due, in large part, to the activist support of the New York State chapter of Y.A.F. A Congressman representing New York's old 43rd Congressional District, Goodell had been appointed to the Senate by Barry Goldwater's arch-nemesis Nelson Rockefeller, the liberal Republican Governor of New York, to fill the seat vacated by the assassination of Robert F. Kennedy, a Democrat. In the Senate, Goodell had moved to the left and thus incurred the enmity of conservatives in the New York State Republican Party, who threw in their lot with Jim Buckley. Buckley served one term in the Senate, then was defeated by Democrat Daniel Patrick Moynihan in 1976.

Mayoral candidacy

In 1965, Buckley ran for mayor of New York City as the candidate for the young Conservative Party, because of his dissatisfaction with the very liberal Republican candidate and fellow Yale alumnus John Lindsay, who later became a Democrat. When asked what he would do if he won the race, Buckley issued his classic response, "I'd demand a recount." (During one televised debate with Lindsay, Buckley declined to use his allotted rebuttal time and instead replied, "I am satisfied to sit back and contemplate my own former eloquence.")

To relieve traffic congestion, Buckley proposed charging cars a fee to enter the central city, and a network of bike lanes. He also opposed a civilian review board for the New York Police Department, which Lindsay had recently introduced to control police corruption and install community policing.[15] Buckley finished third with 13.4 percent of the vote, having unintentionally aided Lindsay's election by taking votes from Democratic candidate Abe Beame.[16]

Firing Line

For many Americans, Buckley's erudite style on his weekly PBS show Firing Line (1966–1999) was their primary exposure to him. In it he displayed a scholarly, and humorous conservatism and was known for his facial expressions, gestures and probing questions of his guests.

Throughout his career as a media figure, Buckley had received much criticism, largely from the American left but also from certain factions on the right, including the John Birch Society, as well as from Objectivists.[17]

Feud with Gore Vidal

Buckley appeared in a series of televised debates with Gore Vidal during the 1968 Democratic Party convention. In their penultimate debate on August 28 of that year, the two disagreed over the actions of the Chicago police and the protesters at the ongoing Democratic Convention in Chicago.

This feud continued the following year in the pages of Esquire, which commissioned an essay from both Buckley and Vidal on the television incident. Buckley's essay "On Experiencing Gore Vidal," was published in the August 1969 issue, and led Vidal to sue for libel. The court threw out Vidal's case.[18] "A Distasteful Encounter with William F. Buckley," was similarly litigated by Buckley. In it Vidal strongly implied that, in 1944, Buckley and unnamed siblings had vandalized a Protestant church in their Sharon, Connecticut, hometown after the pastor's wife had sold a house to a Jewish family. Buckley sued Vidal and Esquire for libel; Vidal counter-claimed for libel against Buckley, citing Buckley's characterization of Vidal's novel Myra Breckenridge as pornography. Both cases were dropped, with Buckley settling for court costs paid by Vidal, while Vidal absorbed his own court costs. Buckley also received an editorial apology in the pages of Esquire as part of the settlement.[18]

The feud was re-opened in 2003 when Esquire re-published the original Vidal essay, at which time further legal action resulted in the same result; Buckley was compensated both personally and for his legal fees, along with an editorial notice and apology in the pages of Esquire, again.

Nonetheless, Buckley also maintained an antipathy towards Vidal's other bête noire, Norman Mailer, calling him "a towering figure in American literary life for sixty years, almost unique in his search for notoriety and absolutely unrivaled in his co-existence with it."[19]

United Nations delegate

In 1973, Buckley served as a delegate to the United Nations. In 1981, after quipping to a reporter that the position he sought in the Reagan administration was "ventriloquist," Buckley informed President-elect (and personal friend) Ronald Reagan that he would decline any official position offered to him. Reagan jokingly replied that that was too bad, because he had wanted to make Buckley ambassador to (then Soviet-occupied) Afghanistan. Buckley replied that he was willing to take the job but only if he were to be supplied with "10 divisions of bodyguards."[20]

Spy novelist

In 1975, in an interview in the Paris Review, Buckley recounted being inspired to write a spy novel by Frederick Forsyth's The Day of the Jackal: "…If I were to write a book of fiction, I'd like to have a whack at something of that nature."[21] He went on to explain that he was determined to avoid the moral ambiguity of Graham Greene and John le Carré. Buckley wrote the 1976 spy novel Saving the Queen, featuring Blackford Oakes as a rule-bound CIA agent; Buckley based the novel in part on his own CIA experiences. Over the next 30 years, Buckley would write another ten novels featuring Oakes. New York Times critic Charlie Rubin wrote that the series "at its best, evokes John O'Hara in its precise sense of place amid simmering class hierarchies."[22]

Buckley was particularly concerned about the view that what the CIA and the KGB were doing were morally equivalent. As he wrote in his memoirs,

I said to Johnny Carson that to say that the CIA and the KGB engage in similar practices is the equivalent of saying that the man who pushes an old lady into the path of a hurtling bus is not to be distinguished from the man who pushes an old lady out of the path of a hurtling bus: on the grounds that, after all, in both cases someone is pushing old ladies around.[1]

Amnesty International

In the late 1960s, Buckley joined the Board of Directors of Amnesty International USA. He resigned in January 1978 in protest over the organization's stance against capital punishment as expressed in its Stockholm Declaration of 1977.

Later career

Buckley participated in an ABC live and very heated debate with scientist Carl Sagan, following the airing of The Day After, a 1983 made-for-television movie about the effects of nuclear war. Sagan argued against nuclear proliferation, while Buckley, a staunch anti-communist, promoted the concept of nuclear deterrence. During the debate, Sagan discussed the concept of nuclear winter and made his famous analogy, equating the arms race to "two sworn enemies standing waist-deep in gasoline, one with three matches, the other with five."

In 1988 Buckley was instrumental in the defeat of liberal Republican Senator Lowell Weicker. Buckley organized a committee to campaign against Weicker and endorsed his Democratic opponent, Connecticut Attorney General Joseph Lieberman[23] Lieberman defeated Weicker by only about 10,000 votes, with critical margins coming from conservative areas of the state that strongly backed George H. W. Bush for President.

In 1991, Buckley received the Presidential Medal of Freedom from President George H. W. Bush. Buckley retired as active editor from National Review in 1990, and relinquished his controlling shares of National Review in June 2004 to a pre-selected board of trustees. The following month he published the memoir Miles Gone By. Buckley continued to write his syndicated newspaper column, as well as opinion pieces for National Review magazine and National Review Online. He remained editor-at-large at the magazine and also conducted lectures, granted occasional radio interviews.[24]

Thoughts on Catholic liturgical change

Regarding the impact of the reforms following the Vatican II Council, Buckley wrote in 1979:

As a Catholic, I have abandoned hope for the liturgy, which, in the typical American church, is as ugly and as maladroit as if it had been composed by Robert Ingersoll and H.L. Mencken for the purpose of driving people away.

Incidentally, the modern liturgists are doing a remarkably good job, attendance at Catholic Mass on Sunday having dropped sharply in the 10 years since a few well-meaning cretins got hold of the power to vernacularize the Mass, and the money to scour the earth in search of the most unmusical men and women to preside over the translation.

The next liturgical ceremony conducted primarily for my benefit, since I have no plans to be beatified or remarried, will be my own funeral; and it is a source of great consolation to me that, at my funeral, I shall be quite dead, and will not need to listen to the accepted replacement for the noble old Latin liturgy. Meanwhile, I am practicing Yoga, so that, at church on Sundays, I can develop the power to tune out everything I hear, while attempting, athwart the general calisthenics, to commune with my Maker, and ask Him first to forgive me my own sins, and implore him, second, not to forgive the people who ruined the Mass.[25]

Views on modern-day conservatism

Buckley criticized certain aspects of policy within the modern conservative movement. Of George W. Bush's presidency, he said, "If you had a European prime minister who experienced what we’ve experienced it would be expected that he would retire or resign."[26] He said that Bush is "conservative," but he is not a "Conservative," and that the president was not elected "as a vessel of the conservative faith." (Buckley would distinguish between so-called "lowercase c" and "Capital C" conservatives, the latter being True conservatives: fiscally conservative and socially Libertarian or libertarian-leaning). According to Jeffrey Hart, Buckley had a "tragic" view of the Iraq war:

He saw it as a disaster and thought that the conservative movement he had created had in effect committed intellectual suicide by failing to maintain critical distance from the Bush administration…. At the end of his life, Buckley believed the movement he made had destroyed itself by supporting the war in Iraq.[27]

Over the course of his career, Buckley's views changed on some issues, such as drug legalization, which he came to favor.[28] In his December 3, 2007 column, Buckley advocated banning tobacco use in America.[29]

About neoconservatives, he said in 2004: "I think those I know, which is most of them, are bright, informed and idealistic, but that they simply overrate the reach of U.S. power and influence."[11]

Death

Buckley died at his home in Stamford, Connecticut, on February 28, 2008; he was found dead at his desk in the study. At the time of his death, he had been suffering from emphysema and diabetes.[30]

In a December 3, 2007 column, Buckley commented on the cause of his emphysema:

Half a year ago my wife died, technically from an infection, but manifestly, at least in part, from a body weakened by 60 years of nonstop smoking. I stayed off the cigarettes but went to the idiocy of cigars inhaled, and suffer now from emphysema, which seems determined to outpace heart disease as a human killer. Stick me in a confessional and ask the question: Sir, if you had the authority, would you forbid smoking in America? You'd get a solemn and contrite, Yes.[29]

Notable members of the Republican political establishment paying tribute to Buckley included President George W. Bush,[31] former Speaker of the House of Representatives Newt Gingrich, and former First Lady Nancy Reagan. Bush said of Buckley, "he influenced a lot of people, including me. He captured the imagination of a lot of people."[32] Gingrich added: Bill Buckley became the indispensable intellectual advocate from whose energy, intelligence, wit, and enthusiasm the best of modern conservatism drew its inspiration and encouragement. ... Buckley began what led to Senator Barry Goldwater and his Conscience of a Conservative that led to the seizing of power by the conservatives from the moderate establishment within the Republican Party. From that emerged Ronald Reagan.[33] Reagan's widow, Nancy, commented, "Ronnie valued Bill's counsel throughout his political life, and after Ronnie died, Bill and Pat were there for me in so many ways."[34]

Linguistic expertise

Buckley was well known for his command of language. Buckley came late to formal instruction in the English language, not learning it until he was seven years old (his first language was Spanish, learned in Mexico, and his second French, learned in Paris).[1] As a consequence, he spoke English with an idiosyncratic accent: something between an old-fashioned, upper class Mid-Atlantic accent and British Received Pronunciation.[35]

Legacy

Buckley referred to himself "on and off" as either libertarian or conservative.[36]

Buckley's writing style was famed for its erudition, wit, and use of uncommon words. Virtually every modern conservative commentator from George Will to Peggy Noonan owes a debt to Buckley's thought and his style.

Buckley was "arguably the most important public intellectual in the United States in the past half century," according to George H. Nash, a historian of the modern American conservative movement. "For an entire generation he was the preeminent voice of American conservatism and its first great ecumenical figure."[37] Buckley's primary intellectual achievement was to fuse traditional American political conservatism with laissez-faire and anti-communism, laying the groundwork for the modern American conservatism of U.S. presidential candidate Barry Goldwater and President Ronald Reagan.

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 William F. Buckley Jr., Miles Gone By: A Literary Autobiography (Washington DC: Regnery Publishing, 2004, ISBN 978-0895260895).

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Valerie Cruice,Once Again, Buckley Takes On Bach The New York Times, October 25, 1992. Retrieved May 12, 2021.

- ↑ Boston Symphony Orchestra Presents 2006 Tanglewood Jazz Festival iBerkshires.com, August 2, 2006. Retrieved May 12, 2021.

- ↑ David Helwig, William F. Buckley Jr: 1925-2008 SooToday, February 27, 2008. Retrieved May 12, 2021.

- ↑ Alexandra Robbins, Secrets of the Tomb: Skull and Bones, the Ivy League, and the Hidden Paths of Power (Boston: Little, Brown, 2002), 41.

- ↑ William F. Buckley, Jr., Who Did What? Real Clear Politics, November 2, 2005. Retrieved May 12, 2021.

- ↑ Jack Trotter, Remembering William F. Buckley, Jr. Chronicles, April/May 2020. Retrieved May 12, 2021.

- ↑ William F. Buckley, Jr. McCarthy and His Enemies: The Record and Its Meaning (Washington, DC: Regnery Publishing, 1954, ISBN 0895264722), 335.

- ↑ Whittaker Chambers, Big Sister is Watching You National Review, January 5, 2005. Retrieved May 12, 2021.

- ↑ Robert W. Tracinski, A Half-Century-Old Attack on Ayn Rand Reminds Us of the Dark Side of Conservatism Capitalism Magazine, January 6, 2005. Retrieved May 12, 2021.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Deborah Sanger, Questions for William F. Buckley: Conservatively Speaking, interview in The New York Times Magazine, July 11, 2004. Retrieved May 12, 2021.

- ↑ William F. Buckley, Jr., "Editorial" National Review, August 1957.

- ↑ Jeet Heer, William F. Buckley: the Gift of Friendship sans everything, February 27, 2008. Retrieved May 12, 2021.

- ↑ William F. Buckley, Jr. Goldwater, the John Birch Society, and Me. Wall Street Journal, February 27, 2008. Retrieved May 12, 2021.

- ↑ Rick Perlstein, Nixonland: The Rise of a President and the Fracturing of America (Scribner, 2009, ISBN 978-0743243032).

- ↑ Sam Tanenhaus, The Buckley Effect The New York Times Magazine, October 2, 2005. Retrieved May 12, 2021.

- ↑ Harry Binswanger, William F. Buckley, Jr.: The Witch-Doctor is Dead Capitalism Magazine, March 10, 2008. Retrieved May 12, 2021.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Vidal Discredited! Esquire apologies to Buckley; picks up legal tab NR, December 14, 2004. Retrieved May 12, 2021.

- ↑ William F. Buckley Jr., Norman Mailer, R.I.P. National Review Online, November 14, 2007. Retrieved May 12, 2021.

- ↑ Ronald Reagan, Reagan: A Life in Letters (Free Press, 2003, ISBN 978-0743219662), 64.

- ↑ Sam Vaughan, William F. Buckley Jr., The Art of Fiction No. 146 Paris Review, Issue 139, Summer 1996. Retrieved May 12, 2021.

- ↑ Charlie Rubin, 'Last Call for Blackford Oakes': Cocktails With Philby The New York Times, July 17, 2005. Retrieved May 12, 2021.

- ↑ William F. Buckley, Jr., Did He Kiss Joe? National Review Online, July 5, 2006. Retrieved May 12, 2021.

- ↑ Dan Schneider, Review of Buckley's autobiography Miles Gone By hackwriters.com, December 2005. Retrieved May 12, 2021.

- ↑ William F. Buckley on the New Mass The Remnant, May 15, 1979. Retrieved May 12, 2021.

- ↑ Buckley: Bush Not A True Conservative CBS News, July 22, 2006. Retrieved May 12, 2021.

- ↑ Jeffrey Hart, Right at the end The American Conservative, March 24, 2008. Retrieved May 12, 2021.

- ↑ On Legalizing Drugs With William F. Buckley The Openmind, 1996. Retrieved May 12, 2021.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 William F. Buckley, Jr. My Smoking Confessional New York Sun, December 3, 2007. Retrieved May 12, 2021.

- ↑ Douglas Martin, William F. Buckley Jr. Is Dead at 82 The New York Times, February 27, 2008. Retrieved May 12, 2021.

- ↑ Statement by the President on Death of William F. Buckley Office of the Press Secretary, the White House, February 27, 2008. Retrieved May 12, 2021.

- ↑ Daniel Trotta, UPDATE 4-US conservative William Buckley dead at 82 Reuters, February 27, 2008. Retrieved May 12, 2021.

- ↑ Newt Gingrich, Reagan, There Was Buckley.

- ↑ Nancy Reagan: Buckley Was a 'Dear Friend' February 27, 2008.

- ↑ Michelle Tsai, Why Did William F. Buckley Jr. talk like that?. Slate, February 28, 2008. Retrieved May 12, 2021.

- ↑ William F. Buckley, Jr. Happy Days Were Here Again: Reflections of a Libertarian Journalist. (New York: Random House, 1993. ISBN 0679403981).

- ↑ WFB JR.: Remembering an Icon Intercollegiate Studies Institute, February 27, 2013. Retrieved May 12, 2021.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Birnbach, Lisa. The Official Preppy Handbook. New York: Workman Publishing Company, Inc., 1980. ISBN 9780894801952.

- Bridges, Linda. Strictly Right: William F. Buckley Jr. and the American Conservative Movement. New York: Wiley, John & Sons, Inc., 2007. ISBN 0471758175.

- Buckley, James Lane. Gleanings from an Unplanned Life: An Annotated Oral History. Wilmington, DE: Intercollegiate Studies Institute, 2006. ISBN 978-1933859118.

- Buckley, Reid. Strictly Speaking. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1999. ISBN 0071346104.

- Buckley, William F., Jr. McCarthy and His Enemies: The Record and Its Meaning. Washington, DC: Regnery Publishing, 1954. ISBN 0895264722

- Buckley, William F., Jr. Happy Days Were Here Again: Reflections of a Libertarian Journalist. New York: Random House, 1993. ISBN 0679403981.

- Buckley, William F., Jr. Miles Gone By: A Literary Autobiography. Regnery Publishing, Inc., 2004. ISBN 978-0895260895

- Gottfried, Paul. The Conservative Movement. Boston: Twayne Publishers, 1993. ISBN 0805797491

- Judis, John B. William F. Buckley, Jr.: Patron Saint of the Conservatives. New York: Touchstone, 1990. ISBN 0671695932

- Lamb, Brian. Booknotes: Stories from American History. New York: Penguin, 2001. ISBN 1586480839.

- Meehan, William F. III. William F. Buckley Jr: A Bibliography. New York: ISI Books, 1990. ISBN 9781882926664

- Merriam-Webster's Dictionary of American Writers. MA: Merriam-Webster, 2001. ISBN 9780877790228

- Miller, David. Chairman Bill: A Biography of William F. Buckley, Jr. New York: iUniverse, 1990. ISBN 9780595400775

- Nash, George H. The Conservative Intellectual Movement in America Since 1945. New York: Basic Books, 2006. ISBN 9780465014019.

- Perlstein, Rick. Nixonland: The Rise of a President and the Fracturing of America. Scribner, 2009. ISBN 978-0743243032

- Reagan, Ronald. Reagan: A Life in Letters. Free Press, 2003. ISBN 978-0743219662

- Robbins, Alexandra. Secrets of the Tomb: Skull and Bones, the Ivy League, and the Hidden Paths of Power. Boston: Little, Brown, 2002. ISBN 0316720917.

- Smith, W. Thomas, Jr. Encyclopedia of the Central Intelligence Agency. New York: Facts on File, 2003. ISBN 0816046670.

- Straus, Tamara. The Literary Almanac: The Best of the Printed Word: 1900 to the Present. New York: High Tide Press, 1997. ISBN 1567313280.

- Winchell, Mark Royden. William F. Buckley, Jr. New York: MacMillan Publishing Company, 1984. ISBN 0805774319.

External links

All links retrieved May 8, 2023.

- William F. Buckley at the Internet Movie Database.

- "A Life on the Right: William F. Buckley," National Public Radio, July 14, 2004.

- "Walking the Road that Buckley Built," by Michael Johns, March 7, 2008.

- The Legacy of William F. Buckley Jr. by Edwin J. Feulner, February 28, 2018, The Heritage Foundation.

| Party Political Offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| New Title | Conservative Party nominee for Mayor of New York City 1965 |

Succeeded by: John Marchi |

| ||||||||

| |||||||||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.