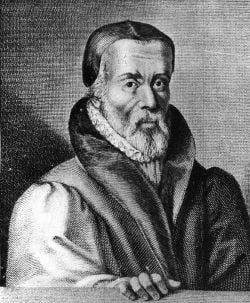

William Tyndale

| William Tyndale | |

Protestant reformer and Bible translator

| |

| Born | ca. 1494 Gloucestershire, England |

|---|---|

| Died | September 6, 1536 near Brussels, Belgium |

William Tyndale (sometimes spelled Tindall or Tyndall) (ca. 1494–September 6, 1536) was a sixteenth century Protestant reformer and scholar who translated the Bible into the Early Modern English of his day. Although a number of partial and complete English translations had been made from the seventh century onward, Tyndale's was the first to take advantage of the new medium of print, which allowed for its wide distribution. In 1535, Tyndale was arrested, jailed in the castle of Vilvoorde outside Brussels, Belgium for more than a year, tried for heresy and treason and then strangled and burnt at the stake in the castle's courtyard. [1] At the time, the Church believed that if lay people had direct access to the Bible they would misinterpret and misunderstand what they read. Possibly, they would question the teaching of the Church and the authority of the priests. By keeping the Bible in Latin, which few other than priests and scholars could, read, the role of the priest as gatekeeper was protected.

Tyndale also made a significant contribution to English through many of his phrases that passed into popular use. His legacy lives on through his continued influence on many subsequent English translations of the Bible. Much of Tyndale's work eventually found its way into the King James Version (or Authorized Version) of the Bible, published in 1611, and, though nominally the work of 54 independent scholars, is based primarily on Tyndale's translations.

Early Life

William Tyndale was born around 1494, probably in one of the villages near Dursley, Gloucestershire. The Tyndales were also known under the name Hychyns (Hitchins), and it was as William Hychyns that he was educated at Magdalen Hall, Oxford (now part of Hertford College), where he was admitted to the Degree of Bachelor of Arts in 1512, the same year he became a subdeacon. He was made Master of Arts in July 1515, three months after he had been ordained into the priesthood. The MA degree allowed him to start studying theology, but the official course did not include the study of scripture. This horrified Tyndale, and he organised private groups for teaching and discussing the scriptures. He was a gifted linguist (fluent in French, Greek, Hebrew, German, Italian, Latin, Spanish and of course his native English) and subsequently went to Cambridge (possibly studying under Erasmus, whose 1503 Enchiridion Militis Christiani — "Handbook of the Christian Knight"—he translated into English), where he is believed to have met Thomas Bilney and John Frith.

Translating the Bible

He became chaplain in the house of Sir John Walsh at Little Sodbury in about 1521, and tutor to his children. His opinions involved him in controversy with his fellow clergymen, and around 1522 he was summoned before the Chancellor of the Diocese of Worcester on a charge of heresy.

Soon afterwards he already determined to translate the Bible into English: he was convinced that the way to God was through His word and that scripture should be available even to common people. Foxe describes an argument with a "learned" but "blasphemous" clergyman, who had asserted to Tyndale that, "We had better be without God's laws than the Pope's." In a swelling of emotion, Tyndale made his prophetic response: "I defy the Pope, and all his laws; and if God spares my life, I will cause the boy that drives the plow in England to know more of the Scriptures than the Pope himself!"[2][3]

Tyndale left for London in 1523 to seek permission to translate the Bible into English and to request other help from the Church. In particular he hoped for support from Bishop Cuthbert Tunstall, a well-known classicist whom Erasmus had praised after working with him on a Greek New Testament, but the bishop, like many highly-placed churchmen, was uncomfortable with the idea of the Bible in the vernacular and told Tyndale he had no room for him in the Bishop's Palace. Tyndale preached and studied "at his book" in London for some time, relying on the help of a cloth merchant, Humphrey Monmouth. He then left England under a pseudonym and landed at Hamburg in 1524 with the work he had done so far on his translation of the New Testament, and in the following year completed his translation, with assistance from Observant friar William Roy.

In 1525, publication of his work by Peter Quentell in Cologne was interrupted by anti-Lutheran influence, and it was not until 1526 that a full edition of the New Testament was produced by the printer Peter Schoeffer in Worms, a safe city for church reformers. More copies were soon being printed in Antwerp. The book was smuggled into England and Scotland, and was condemned in October 1526 by Tunstall, who issued warnings to booksellers and had copies burned in public.

Persecution

Following the publication of the New Testament, Cardinal Wolsey condemned Tyndale as a heretic and demanded his arrest.

Tyndale went into hiding, possibly for a time in Hamburg, and carried on working. He revised his New Testament and began translating the Old Testament and writing various treatises. In 1530, he wrote The Practyse of Prelates, which seemed to move him briefly to the Catholic side through its opposition to Henry VIII's divorce. This resulted in the king's wrath being directed at him: he asked the emperor Charles V to have Tyndale seized and returned to England.

Eventually, he was betrayed to the authorities. He was kidnapped in Antwerp in 1535, betrayed by Henry Phillips, and held in the castle of Vilvoorde near Brussels.

He was tried on a charge of heresy in 1536 and condemned to the stake, despite Thomas Cromwell's intercession on his behalf. Tyndale was strangled and his body burned at the stake on September 6, 1536. His final words reportedly were, "Oh Lord, open the King of England's eyes."[4]

Tyndale's legacy

In translating the Bible, Tyndale introduced new words into the English language:

- Jehovah (from a transliterated Hebrew construction in the Old Testament; composed from the tetragrammaton YHWH and the vowels of adonai: YaHoWaH)

- Passover (as the name for the Jewish holiday, Pesach or Pesah),

- Atonement (= at + onement), which goes beyond mere "reconciliation" to mean "to unite" or "to cover," which springs from the Hebrew kippur, the Old Testament version of kippur being the covering of doorposts with blood, or "Day of Atonement."

- scapegoat (the goat that bears the sins and iniquities of the people in Leviticus Chapter 16)

He also coined such familiar phrases as:

- let there be light

- the powers that be

- my brother's keeper

- the salt of the earth

- a law unto themselves

- filthy lucre

- it came to pass

- gave up the ghost

Some of the new words and phrases introduced by Tyndale did not sit well with the hierarchy of the Roman Catholic Church, using words like 'Overseer' rather than 'Bishop' and 'Elder' rather than 'Priest', and (very controversially), 'congregation' rather than 'Church' and 'love' rather than 'charity'. Tyndale contended (with Erasmus) that the Greek New Testament did not support the traditional Roman Catholic readings.

Contention from Roman Catholics came from real or perceived errors in translation. Thomas More commented that searching for errors in the Tyndale Bible was similar to searching for water in the sea. Bishop Cuthbert Tunstall of London declared that there were upwards of 2,000 errors in Tyndale's Bible. Tunstall in 1523 had denied Tyndale the permission required under the Constitutions of Oxford (1409), that were still in force, to translate the Bible into English, and forced him into exile.

In response to allegations of inaccuracies in his translation in the New Testament, Tyndale wrote that he never intentionally altered or misrepresented any of the Bible in his translation, and would never do so.

While translating, Tyndale controversially followed Erasmus' (1522) Greek edition of the New Testament. In his Preface to his 1534 New Testament ("WT unto the Reader"), he not only goes into some detail about the Greek tenses but also points out that there is often a Hebrew idiom underlying the Greek. The Tyndale Society adduces much further evidence to show that his translations were made directly from the original Hebrew and Greek sources he had at his disposal. For example, the Prolegomena in Mombert's William Tyndale's Five Books of Moses show that Tyndale's Pentateuch is a translation of the Hebrew original.

Of the first (1526) edition of Tyndale's New Testament, only three copies survive. The only complete copy is part of the Bible Collection of Württembergische Landesbibliothek, Stuttgart. The copy of the British Library is almost complete, lacking only the title page and list of contents.

Tyndale's Long-Term Impact on the English Bible

The men who translated the Revised Standard Version in the 1940s noted that Tyndale's translation inspired the great translations to follow, including the Great Bible of 1539, the Geneva Bible of 1560, the Bishops' Bible of 1568, the Douay-Rheims Bible of 1582–1609, and the King James Version of 1611, of which the RSV translators noted: "It [the KJV] kept felicitous phrases and apt expressions, from whatever source, which had stood the test of public usage. It owed most, especially in the New Testament, to Tyndale."

Many of the great English versions since then have drawn inspiration from Tyndale, such as the Revised Standard Version, the New American Standard Bible, and the English Standard Version. Even the paraphrases like the Living Bible and the New Living Translation have been inspired by the same desire to make the Bible understandable to Tyndale's proverbial ploughboy.

Memorials

A bronze statue by Sir Joseph Boehm commemorating the life and work of Tyndale was erected in Victoria Embankment Gardens on the Thames Embankment, London in 1884. It shows the reformer's right hand on an open Bible, which in turn is resting on an early printing press.

There is also a memorial tower, the Tyndale Monument, erected in 1866 and prominent for miles around, on a hill above his birthplace of North Nibley.

The site in Vilvoorde, Belgium (15 minutes north of Brussels by train) where Tyndale was burned is also marked by a memorial. It was erected in 1913 by Friends of the Trinitarian Bible Society of London and the Belgium Bible Society.

He is commemorated in the Calendar of Saints of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America as a translator and martyr on October 6.

Tyndale University College and Seminary, a Christian university college and seminary in Toronto, is named after William Tyndale.

Notes

- ↑ English Bible History, Greatsite Marketing. Retrieved August 18, 2007.

- ↑ Lecture by Dom Henry Wansbrough OSB MA (Oxon) STL LSS Retrieved August 18, 2007.

- ↑ Foxe's Book of Martyrs, Chap XII Retrieved August 18, 2007.

- ↑ The Betrayal and Death of William Tyndale, Greatsite Marketing. Retrieved August 18, 2007.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Bobrick, Benson. Wide as the waters: the story of the English Bible and the revolution it inspired. New York: Simon & Schuster 2001. ISBN 9780684847474

- Daniell, David. William Tyndale: a biography. New Haven: Yale University Press 1994. ISBN 9780300061321

- Tyndale, William, and David Daniell. Tyndale's New Testament. New Haven, Conn: Yale University Press 1989. ISBN 9780300044195

External links

All links retrieved May 13, 2023.

- Tyndale House Publishers

- Talk on the Tyndale New Testament by British Library curator

- Tyndale Society homepage

- Works by William Tyndale. Project Gutenberg

- Find A Grave Entry

- William Tyndale

- Why William Tyndale Lived and Died

- Canadian Christian education institute named after William Tyndale

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.